BREAKING DOWN THE WRITING PROCESS

If you like to write at the last minute, and if your idea of the “last minute” is the night before a paper is due, you’re going to have to change your ways.

But here’s the good news. Whether you’re writing a two-page paper or a book, the overall approach can be essentially the same. You need only to break down the writing process into manageable bits that you can tackle one at a time.

So let’s break down the writing process. Here are (roughly) the steps that writers go through when they do their work, as well as strategies for tackling each step.

Step One: Reading. Writing starts here, long before you pick up your pen. Make sure that you get the most out of what you read. Follow the critical reading guidelines; make copious notes; review the notes to get ideas; make sure you understand everything you’re reading.

Step Two: Procrastinating. You know you (almost) all do it: you leave class intending to get started on the paper right away - so you say, “I’ll start working right away - as soon as I finish ______.” And an hour after you decided to start working ‘right away,’ you find yourself lifting weights, watching TV, cleaning out your garage or making jam.

It’s hard to skip this stage. So don’t! Make room for it. As you start to make more room for writing assignments, allow yourself a little bit of time to do whatever it is you do to procrastinate right now. You can control this part without eliminating it.

Step Two: Getting ideas. Now you’ve finished replacing your car’s air filter or used up all your cellphone minutes, it’s time to get writing. But what if you get stuck? Try one of the following:

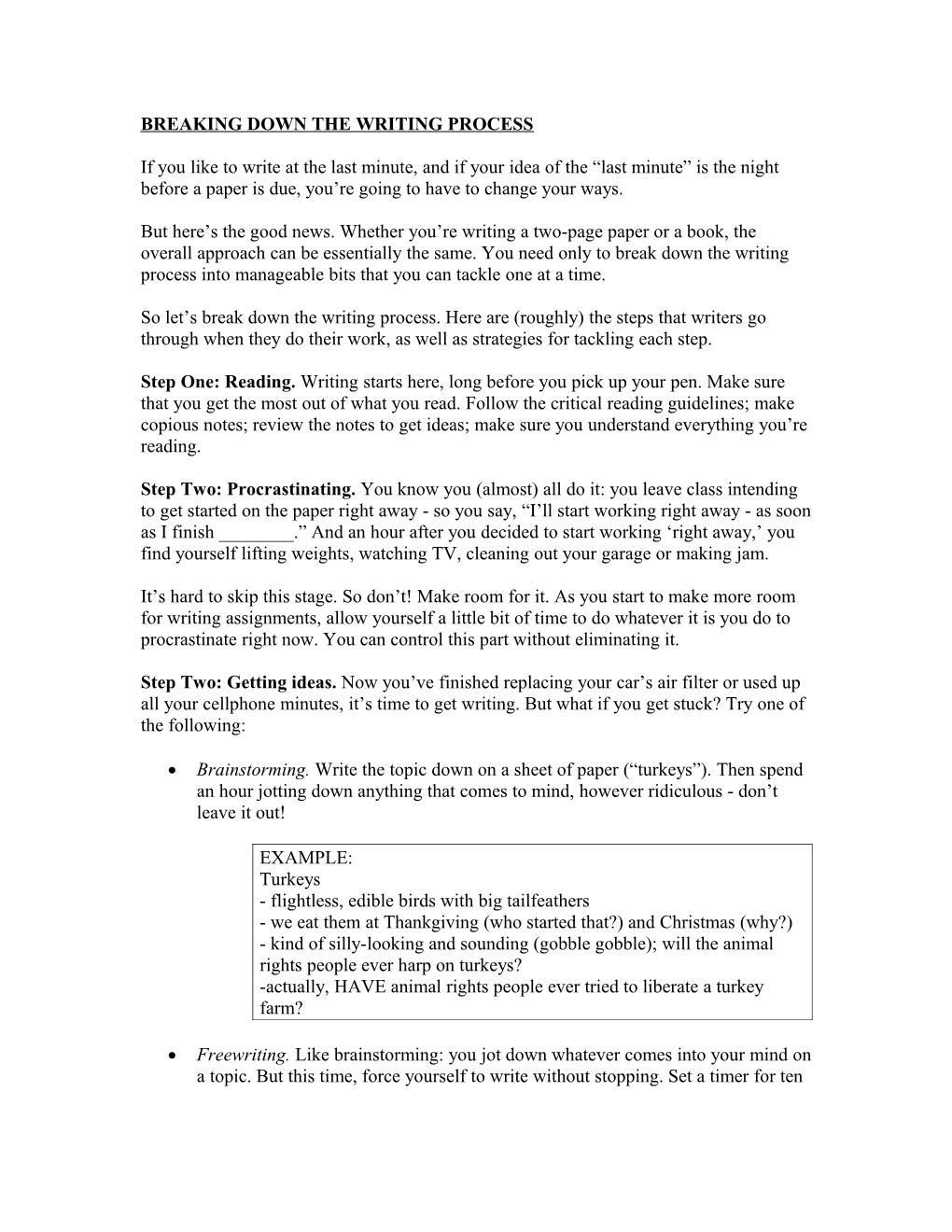

Brainstorming. Write the topic down on a sheet of paper (“turkeys”). Then spend an hour jotting down anything that comes to mind, however ridiculous - don’t leave it out!

EXAMPLE: Turkeys - flightless, edible birds with big tailfeathers - we eat them at Thankgiving (who started that?) and Christmas (why?) - kind of silly-looking and sounding (gobble gobble); will the animal rights people ever harp on turkeys? -actually, HAVE animal rights people ever tried to liberate a turkey farm?

Freewriting. Like brainstorming: you jot down whatever comes into your mind on a topic. But this time, force yourself to write without stopping. Set a timer for ten minutes, and don’t let your fingers rest until the ten minutes are up. Believe it or not, this technique can really work.

EXAMPLE: Turkeys. Let’s see: I like to eat them - the triptophan thing is apparently just a rumor, though, you get sleepy after TGVG because you eat too much, not because the turkey meat has a special sedative in it! - turkey sandwiches with mayo, very nice. Ground turkey: yuck. Processed turkey: double yuck. Not the world’s most versatile meat. Ground turkey cooking smells like a high school locker room at 99 degrees. Turkey turkey - more ideas? - it’s a very American thing, you always think of Thanksgiving though the Euros also eat it at Christmas - not sure if other cuisines eat turkey? Indigenous to the US maybe? It’s very dry! a real pain to roast properly, imho not worth the effort - Benjamin Franklin wanted to make the turkey a national bird instead of the eagle. What would that have done for American foreign policy: a turkey on the embassy insignia instead of an eagle....!!!

Clustering. Like brainstorming again, only this time, you try to organize your jottings spatially on the page so that you cluster similar ideas together.

EXAMPLE:

not versatile a lot of trouble like the eagle, an tasty though when cooked emblem for U.S.; flightless symbolic significance large tailfeathers indigenous to US TURKEY domesticated

humorous, hard to take seriously ceremonial meals:

not a target for PETA’s efforts! Thanksgiving Christmas (US and abroad) Use the modes. These give you a fresh angle on your subject, and can trigger a profitable brainstorm (for more on the modes, keep reading).

EXAMPLE: What do I write about turkeys?

Compare & contrast: turkeys v. eagles - similar: indigenous to the US, both considered for mascots for the country, both important American symbols (eagle is the US emblem, the turkey is the Thanksgiving bird) - different: turkeys are flightless, edible, farmed (not wild), plentiful (not endangered), kind of silly with all that gobbling (not majestic), big, vivid red flaps on their necks, big tailfeathers.

Argument: We should eat more turkey - it’s healthy (properties of turkey meat) - it’s easy to raise (history of domestication of turkey) - it’s tasty (some turkey recipes)

Step Three: Drafting. Now that you have gotten yourself thinking, you need to get started. You’ll need:

A working thesis. It doesn’t matter if you stick to it, but look at what you’ve got, and ask yourself: What point can I make? What shall I say? Pick something and start there.

Examples: The turkey is an important American symbol. We should eat more turkey. Eating turkeys is cruel.

An outline. Look at your thesis, and imagine a reader asking, “Why?” or, “In what way?” Write down one-sentence answers, with brief notes of the kinds of details that would support them. This approach can help you find topic sentences.

Example: The turkey is an important American symbol. [In what way? - note how topic sentences answer this question:] - It’s central to an American festival (TG: recipes, stories) - Franklin wanted it to be the national bird (it’s useful, native) - It’s indigenous to the US (cultivated by native Americans, etc.) A rough draft. Now you have an idea of your point and the possible paragraphs, take one paragraph at a time and flesh it out. Try doing them out of order; it helps you work on the paper a bit at a time.

Example: The turkey is central to the uniquely American festival of Thanksgiving. Legend has it that the native Americans first introduced the bird to the pilgrims at the first Thanksgiving festival, and thus it symbolizes the early (and unfortunately shortlived) friendship that existed at first between the new arrivals and the inhabitants of the New World. Since then, the turkey has become a fixture of the celebration. However, it is not a particularly easy bird to deal with. Recipes abound for rescuing a burned turkey, roasting the uncooperative bird to succulence, and of course, what to do with the preposterous amount of leftovers: curried, stewed, . It’s not so much a delicious entree as a challenge. Maybe this too makes it very American: we love a challenge.

Final shaping: writing the introduction & conclusion. Movie directors don’t shoot scenes in the order that they appear in the movie: why should you write your paper in the order that the reader will read it? Leave the introduction and conclusion until last. Once you have a clear idea of your point and how it is developed, you will find writing a quick introduction and conclusion fairly painless. A handout on introduction and conclusion strategies is included.

Step Four: Peer Response. At this stage, you should get input from peers. (See the handout on Peer Response for details.)

Step Five: Revision. This is the most important step in the process. Revision does NOT mean correcting grammar or punctuation. Revision means, literally, “re-seeing” - looking at your whole work in a new light. You might not want to make changes. But after reviewing your work with peers, you might realize that your paper doesn’t really relate to the thesis; that your support isn’t adequate; that one paragraph is far too long, or too short, or redundant; that your thinking process is unfinished, and you “really” want to say something else; you might even find that you no longer even believe your original opinion. Revision can mean adding a few sentences, or restructuring the whole paper.

If there is one thing you learn in ENGL 100, it should be that this stage of writing is indispensable. You will need to cultivate a two-draft approach to writing papers of any substance or merit. You can revise your paper effectively by asking yourself the following:

“What am I saying here?” See if you can clearly pick out the thesis and supporting statements and rephrase them in a few sentences. “Where am I going with it?” Is this idea really complete? Or do you now find that you can think of a better way to say it, or a better way to support it? Your thesis might now seem a bit too general. “Does the paper work?” How is it shaped? How are the ideas supported? Have you integrated your reading, used sentence styles, taken pains to include concrete details?

Step Six: Proofreading. Once the paper is completely finished, you can think about commas, complete sentences, and the other fun stuff. Here are some tips:

Give yourself the time you need. If you habitually make lots of proofreading errors, leave plenty of time for this stage. Get help from a professional.... The Writing Center instructors are there to help you learn any rules you might need to know, and to practice techniques for effective proofreading ... But do your own proofreading! Once you’ve established what grammar rules you don’t know, where to look them up, and how to spot typos and other errors, learn to do the proofreading yourself. Make a list of what to look for. Don’t look at sentences and think, “What’s wrong?” You’ll only invent problems where none exist, and perhaps miss those that do. Work with a teacher to draw up a list of your specific weaknesses - incomplete sentences, tenses, spelling, and so on - and then look specifically for those problems, one at a time. Start at the end. Look at the last sentence first. Reading them out of sequence helps to keep you focused on the grammar.

Step Seven: Celebration. If you’ve followed all six steps, you’ve done some serious work. Give yourself credit. Writing is hard - relax between assignments, even if it’s only for an hour or so.