Analysing Quotations...

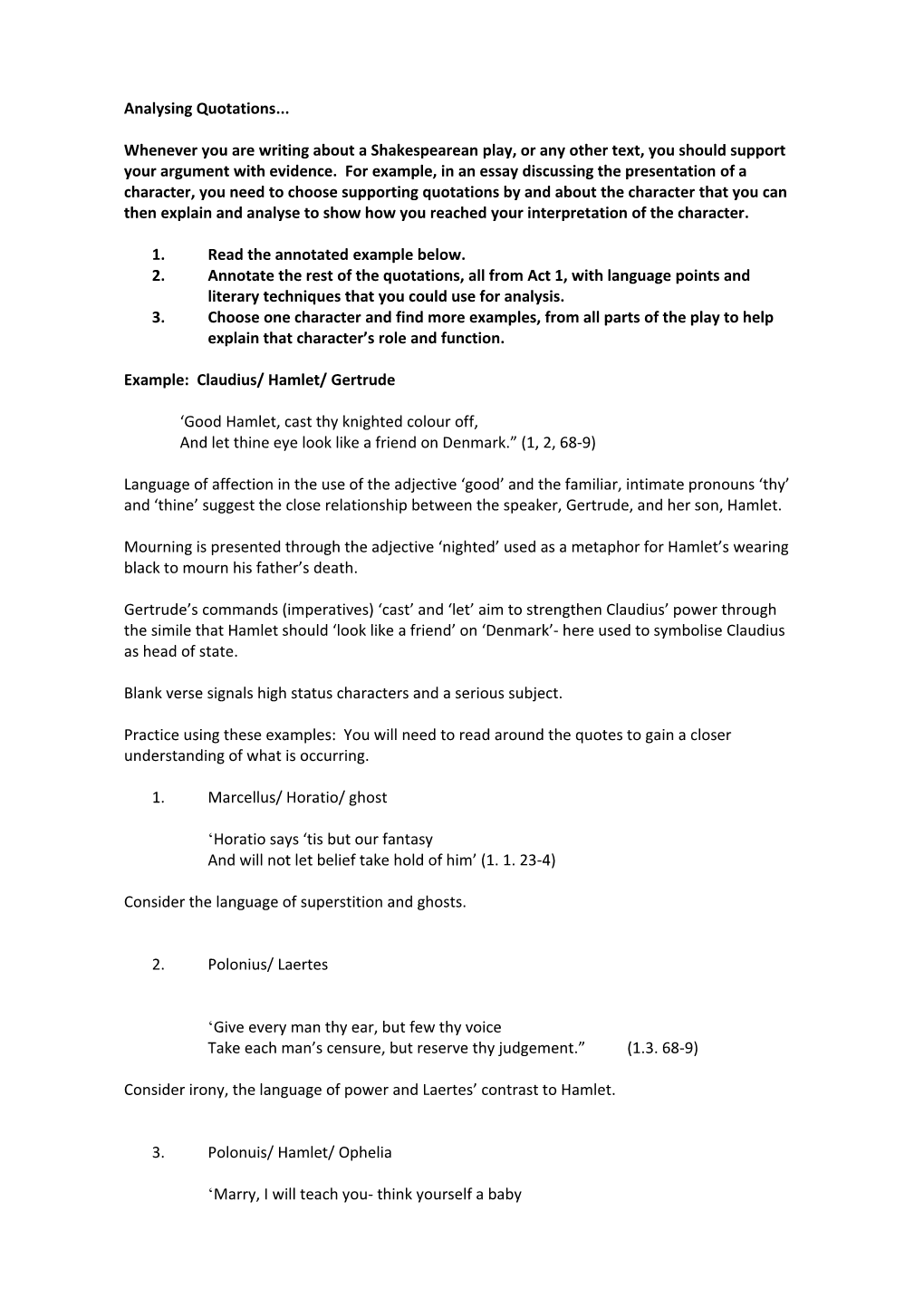

Whenever you are writing about a Shakespearean play, or any other text, you should support your argument with evidence. For example, in an essay discussing the presentation of a character, you need to choose supporting quotations by and about the character that you can then explain and analyse to show how you reached your interpretation of the character.

1. Read the annotated example below. 2. Annotate the rest of the quotations, all from Act 1, with language points and literary techniques that you could use for analysis. 3. Choose one character and find more examples, from all parts of the play to help explain that character’s role and function.

Example: Claudius/ Hamlet/ Gertrude

‘Good Hamlet, cast thy knighted colour off, And let thine eye look like a friend on Denmark.” (1, 2, 68-9)

Language of affection in the use of the adjective ‘good’ and the familiar, intimate pronouns ‘thy’ and ‘thine’ suggest the close relationship between the speaker, Gertrude, and her son, Hamlet.

Mourning is presented through the adjective ‘nighted’ used as a metaphor for Hamlet’s wearing black to mourn his father’s death.

Gertrude’s commands (imperatives) ‘cast’ and ‘let’ aim to strengthen Claudius’ power through the simile that Hamlet should ‘look like a friend’ on ‘Denmark’- here used to symbolise Claudius as head of state.

Blank verse signals high status characters and a serious subject.

Practice using these examples: You will need to read around the quotes to gain a closer understanding of what is occurring.

1. Marcellus/ Horatio/ ghost

‘Horatio says ‘tis but our fantasy And will not let belief take hold of him’ (1. 1. 23-4)

Consider the language of superstition and ghosts.

2. Polonius/ Laertes

‘Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice Take each man’s censure, but reserve thy judgement.” (1.3. 68-9)

Consider irony, the language of power and Laertes’ contrast to Hamlet.

3. Polonuis/ Hamlet/ Ophelia

‘Marry, I will teach you- think yourself a baby That you have ta’en these true tenders for pay Which are not sterling.” (1.3. 105-7)

Consider imagery- e.g. linked to money value, language of power.

4. Fortinbras/ Claudius

‘... young Fortinbras Holding a weak supposal of our worth, Or thinking by our late dear brother’s death Our state to be disjointed and out of frame’ (1. 2. 17-20) Consider dramatic irony, language to present unease and corruption, contrast between characters, pronoun choice to convey power.

5. Hamlet/ ghost

‘Angels and ministers of grace defend us! Be thou a spirit of health, or goblin damned, Bring with thee airs from heaven, or blasts from hell,’ (1. 3. 39-41)

Consider punctuation to convey shock, contrasting pairs, pronoun choice. Understanding Hamlet’s ghost scene

When Hamlet and his father’s ghost finally meet in Act 1 Scene 5, the ghost must:

Convince Hamlet that his story is worth listening to

Explain how he was murdered by his brother

In the following two activities you will imagine how Hamlet could use the ghost’s words to prepare the Players to re-enact the murder as a way of trapping Claudius.

Activity 1- Use the following quotations to design the text and images for a poster that will create suspense for the audience and advertise the play to be performed in Act 3 Scene 2:

What the text says: What it really means: Illustration for the Players’ poster:

‘I am thy father’s spirit, E.G. ‘I really am your father’s You could draw the ghost in Doomed for a certain term ghost and I must walk every armour or King’s robes with a To walk the night,’ night.’ moon above him to indicate (Act 1, Scene 5, lines ) that it is night.

‘And for the day confined to fast in fires,’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

‘ I could a take unfold whose lightest word/ Would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

‘Make thy two eyes like stars start from their spheres,’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

‘ Thy knotted and combined locks to part,’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

‘ And each particular hair to stand an end, Like quills upon the fretful porpentine.’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines ) Activity 2: Next, the ghost tells Hamlet (and audience) how he died. Use the following quotations to storyboard the ghost’s explanation of how he was killed for the Players’ rehersal of ‘The Dumb Show’ and ‘The Mousetrap’: What the text says: What it really means: Illustration for the Players’ rehersal:

‘...sleeping within my orchard, My custom always of the afternoon,... Thy uncle stole/ With juice of cursed hebonon in a vial,’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

‘ And in the porches of mine ears did pour/ The leperous distilment,’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

‘ ...swift as quicksilver it courses through/ The natural gates and alleys of the body.’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

‘ And with a sudden vigour it doth posset/ And curd, like eager droppings into milk,/ The thin and wholesome blood;’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

‘...so did it mine, And a most instant tetter bar’d about/ Most lazar-like with vile and loathsome crust/ Al my smooth body...’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

‘ Thus was I, sleeping, by a brother’s hand,/ Of life, of crown, of queen at once dispatch’d,’ (Act 1, Scene 5, lines )

Next look at how the Players re-enact this scene in Act 3 Scene 2 (stage directions for The Dumb Show and The Mosuetrap) Imagery of Sickness and Decay

Find the remaining information for the three quotations provided and then add six complete ones of your own.

Quotation Location in the Significance play

‘I am sick at heart’ Act 1, Scene 1

‘’tis an unweeded garden’ References to weeds are common in this play and reflect the spread of unchecked corruption.

Act 1, Scene 4, This image of decay is a reference to line the ‘rotten’ core of Denmark. There are signs (smell) that something is corrupt (rotten) but it is not visible to begin with. The decay also spreads as the play develops- most characters are destroyed by Claudius’ scheming. Other handy Hamlet quotes

Location Quote Relevance 1, 1, 8 I am sick at heart The state of Denmark is ‘ill’ 1, 2, 1 Dear brother’s death Claudius’ sycophancy (servility, obsequious flattery, and other fawning behaviour) 1, 2, 135 ‘’tis an unweeded garden’ Imagery of sickness and decay 1, 2, 146 Frailty thy name is woman Hamlet’s obsession 1, 4, 90 Something is rotten in the state of Imagery of sickness and decay Denmark 1, 5, 86 Leave her to heaven Ghost’s request to Hamlet re Gertrude 1, 5, 108 That one may smile, and smile, and still Hamlet re Claudius be a villain. 1, 5, 172 Antic disposition Hamlet’s feigned madness 1, 5, 188-9 The time is out of joint; O cursed spite Hamlet’s reluctance to take revenge That ever I was born to set it right. 2, 1, 102 ... the very ecstasy of love Polonius’ view of Hamlet’s madness 2, 2, 57 His father’s death and our o’erhasty Gertrude’s reason for Hamlet’s marriage madness. 2, 2, 162 I’ll loose my daughter to him Polonius uses Ophelia 3, 1, 152 O what a noble mind is here o’erthrown Ophelia believes Hamlet’s madness 3, 4, 64 Like a mildew’d, blasting his wholesome Sickness and decay imagery brother 3, 4, 110 Whet thy almost blunted purpose The ghost’s second visit/ Hamlet’s delay 3, 4, 151 ...do not spread compost on the weeds Weeds imagery- decay of Denmark to make them ranker 3, 4, 199 I have no life to breathe/ What thou Gertrude promises to lie for Hamlet hast said to me 5, 1, 250 ...this is I/ Hamlet the Dane Hamlet’s new found decisiveness 5, 2, 216 If it be now, ‘tis not to come...Let be Hamlet’s resignation to death 5, 2, 340 ... tell my story Hamelt says to Horatio as he is dying.

VERSE: BLANK VERSE and IAMBIC PENTAMETER- Examples are all from The Merchant of Venice

Why do we find Shakespeare difficult? It’s in a 400 year old language and therefore hard to understand. We do not identify with many of the expressions or the humour. It’s mostly written in blank verse, iambic pentameter.

Blank verse is simply verse that doesn’t necessary rhyme. Iambic pentameter is a form of verse that was instantly recognisable to the Elizabethans and used by most dramatists of the day.

Iambic - from iambus: a rhythmic foot of stressed and unstressed syllables, de-dum.

Pentameter - from the Latin for five (Pentagon, pentangle) tells us how many feet are in each line.

De-dum, de-dum, de-dum, de-dum, de-dum. Each line consist of ten syllables, alternatively stressed and unstressed.

“The qual it ty of mer cy is not strained. It drop peth as the gen tle rain from Heaven.”

“To be or not to be that is the question.”

“Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow Creeps in this petty pace from day to day.”

In Northern Broadsides we speak with northern accents. The hard granite stone consonants and short vowels of the northern voice are perfect for the rhythm and pulses of iambic pentameter.

The first line of the play The Merchant of Venice, said by Antonio demonstrates the use of iambic pentameter.

“In sooth I know not why I am so sad.”

Every alternative word or syllable is emphasised, the last one in the line being the loudest.

“In sooth I know not why I am so sad .”

If you take out the unaccented words we are left with:

“sooth, know, why, am, sad.”

These emphasised words are the only ones needed to tell the story. Shakespeare has done this with almost every line of the play. The groundlings were not sophisticated people and the theatregoers were not there to study the play. They were there for entertainment. Audiences were happy just to understand and enjoy the play for what it was. Nevertheless, it is a very clever feat to place every word in the place it will do the best job. The whole play is a poem. It is like a music symphony, drifting in and out of verse crescendos and quiet sections throughout. You will also find he often puts a rhyming couplet at the end of a scene. This tells the audience when the “commercial breaks” are coming, so they can cough or shift in their seat before the next scene. Limericks:

Modern audiences do not instantly recognise Iambic pentameter but a form of verse they are familiar with is the limerick. This is a limerick to demonstrate blank verse.

There was a young man from Dundee, Got stung on the leg by a wasp. When asked if it hurt, He said “No not a bit. He can do it again if he wants.”

This does not rhyme but we know it is in verse. We know it is in verse because it has a rhythm.

De-dum diddy-dum diddy-dum De-dum diddy-dum diddy-dum De-dum diddy-dum De-dum diddy-dum De-dum diddy-dum diddy-dum

The rhythm of the limerick is as recognisable to us as the rhythm of iambic pentameter (De-dum, de- dum, de-dum, de-dum, de-dum) was to the Elizabethans. What Shakespeare does is to take this recognisable rhythm and he plays with it to make a point. This is a limerick to demonstrate this.

There was a young fellow from Tyne, Who tried to put words into rhyme. The only thing was, He failed because He always tried to put far too many, much too many words into the last line.

The main purpose of Iambic pentameter was not so that it could be studied 400 years later but as an aid to the actor. It tells the actor how to say the line by showing where the emphasis should fall.

Making two characters share the same line displays the pace and thought links of the two characters about the same subject.

Portia: There take it prince and if my form lie there Then I am yours.

Morocco: Oh hell! What have we here?

This is emphasized more in the repetitive exchanges of “In such a night” between Lorenzo and Jessica at the beginning of Act 5.

Not all verse is written in iambic pentameter, the poems in the caskets are deliberately different. For instance in the gold casket, written in a verse called tetrameter, the last word of every line rhymes with gold.

The pulse of the iambic pentameter verse also echoes the heartbeat and therefore corresponds with emotions and feelings.

Sometimes different characters will use an alternate rhythm or speak in prose to show their emotions or relationships to each other. For example, Shylock and Tubal speak in prose to each other, not only because of the informality between friends but because when Shylock hears about Antonio’s losses and his daughter’s spending he is not in control of his feelings. Launcelot Gobbo speaks in prose because he is a servant and a comic character. Solanio and Salerio are city boys and would normally speak in verse but in Act 3 Scene 1 they are just mates having a chat and therefore speak in prose.