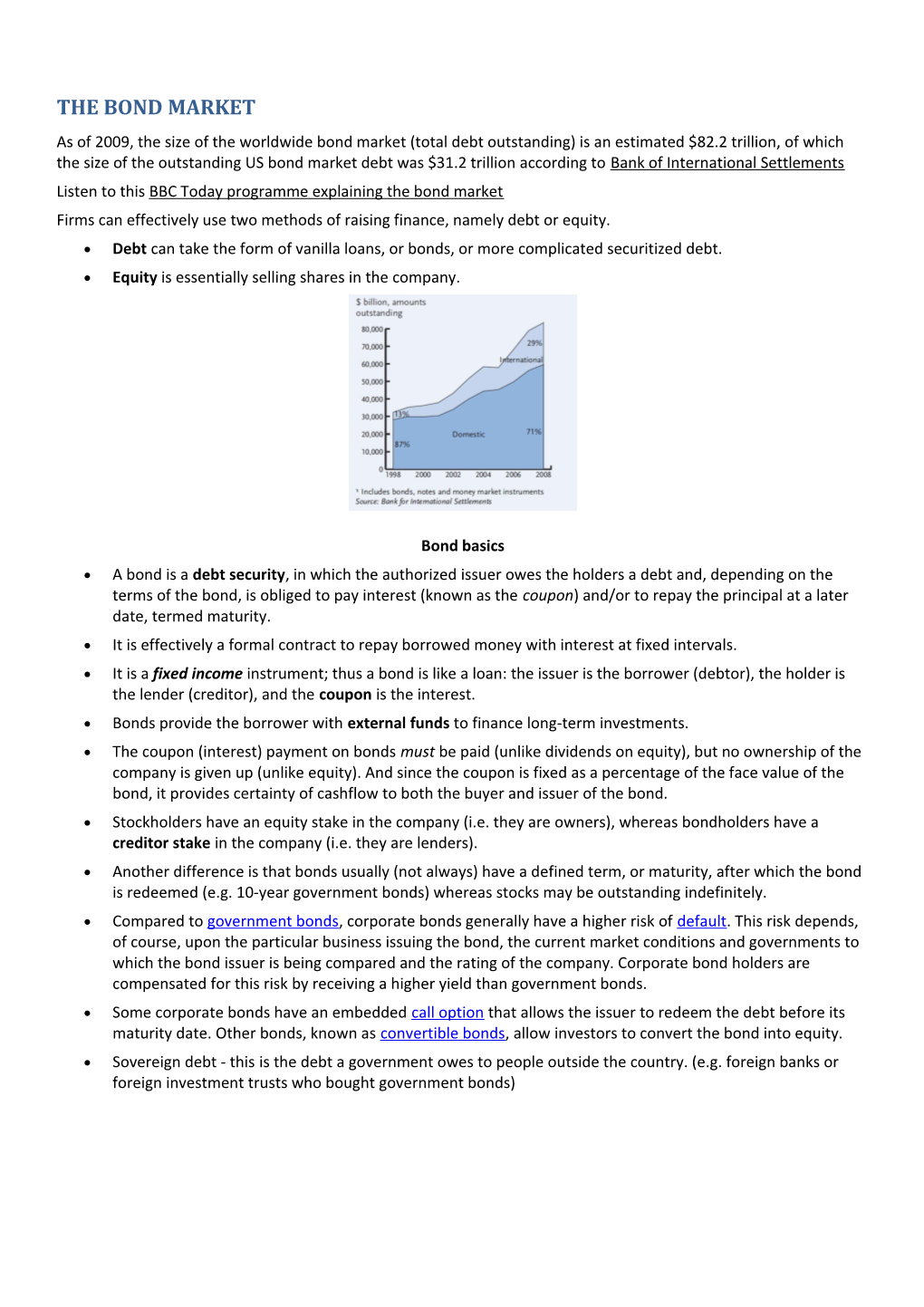

THE BOND MARKET As of 2009, the size of the worldwide bond market (total debt outstanding) is an estimated $82.2 trillion, of which the size of the outstanding US bond market debt was $31.2 trillion according to Bank of International Settlements Listen to this BBC Today programme explaining the bond market Firms can effectively use two methods of raising finance, namely debt or equity. Debt can take the form of vanilla loans, or bonds, or more complicated securitized debt. Equity is essentially selling shares in the company.

Bond basics A bond is a debt security, in which the authorized issuer owes the holders a debt and, depending on the terms of the bond, is obliged to pay interest (known as the coupon) and/or to repay the principal at a later date, termed maturity. It is effectively a formal contract to repay borrowed money with interest at fixed intervals. It is a fixed income instrument; thus a bond is like a loan: the issuer is the borrower (debtor), the holder is the lender (creditor), and the coupon is the interest. Bonds provide the borrower with external funds to finance long-term investments. The coupon (interest) payment on bonds must be paid (unlike dividends on equity), but no ownership of the company is given up (unlike equity). And since the coupon is fixed as a percentage of the face value of the bond, it provides certainty of cashflow to both the buyer and issuer of the bond. Stockholders have an equity stake in the company (i.e. they are owners), whereas bondholders have a creditor stake in the company (i.e. they are lenders). Another difference is that bonds usually (not always) have a defined term, or maturity, after which the bond is redeemed (e.g. 10-year government bonds) whereas stocks may be outstanding indefinitely. Compared to government bonds, corporate bonds generally have a higher risk of default. This risk depends, of course, upon the particular business issuing the bond, the current market conditions and governments to which the bond issuer is being compared and the rating of the company. Corporate bond holders are compensated for this risk by receiving a higher yield than government bonds. Some corporate bonds have an embedded call option that allows the issuer to redeem the debt before its maturity date. Other bonds, known as convertible bonds, allow investors to convert the bond into equity. Sovereign debt - this is the debt a government owes to people outside the country. (e.g. foreign banks or foreign investment trusts who bought government bonds) The bond market This is an international wholesale market where bonds are bought and sold. 90% of bonds are held by institutional investors such as insurance companies, pension funds 30% of new bonds are issued in the London capital market London has a 70% market share in global dealing in secondary bonds (already issued) The main issuers of bonds are large companies and national governments and international organisations Fixed interest bonds - pays the holder of a bond a fixed cash payment every six months Index-linked bonds - interest payments and the loan itself is adjusted in line with the retail price index

Rating bonds All bonds rated between AAA and BBB are called 'investment grade', and are at the lower-risk area of the bond market. Bonds rated BB or below are labeled 'high yield' or 'junk bonds.' A junk bond will offer attractive interest payments but the company behind it could well go bust- leaving the investor with nothing. Equities tend to offer a higher return over the long term but are more risky in the short term (Since 1900, the average annual return on equities has been 5.6% in real terms. For UK government bonds it has been 1.3%, according to the annual returns report by the London Business School and the investment bank ABN Amro). Meeting the interest repayments Because issuing bonds is a way of taking on more debt, it is essential for both corporates and governments to be able to service these debts. The most successful bond issuers have strong stable cash flow to fund the coupon payments. For example Walmart sold a 32-year £1bn bond in 2007 Pension funds are attracted to long dated bonds due to the need to match their long term liabilities. For example Tesco’s 2007 £500million 50 year bond sold out in 2 hours and was 4 times oversubscribed. Bond markets are less developed in Britain than in the United States, where every municipality issues bonds to fund infrastructure. Britain’s public sector bond market was virtually shut down by Margaret Thatcher when she sought to get a grip on spendthrift local authorities - local authorities for example have been prevented for many years from borrowing to finance increased spending on new council house-building.

The surge in activity in the bond markets In recent months there has been a big rise in interest in and use of the bond market to raise fresh capital. Good examples of corporates using the bond market include: Cambridge University (£400m issue) - details here details here Harvard University (2009, $2.5 billion; 2010, $400m) - details here Manchester United (£500m) - details here Virgin Media (Nov 2009 - £350 million; Jan 2010 - $2.4 billion of first-lien bonds in dollars and pounds at its lowest rates ever) - details here details here Icahn Enterprises LP - controlled by billionaire Carl C. Icahn, plans to sell $2 billion of bonds - details here Princeton (2009, $1 billion) University of California (2009, $1.6 billion) Alrosa, Russia’s diamond monopoly, may sell as much as $1 billion in foreign-currency bonds in the second half of 2010 Russia is preparing to launch its first auction of government bonds since sparking a crisis and crippling its financial reputation by defaulting on its debt a decade ago. Why has there been a surge in the use of the bond market in recent years? Stock markets have recovered well after the credit crunch / recession but bond markets have become even more popular - there are several underlying reasons. The crunch: Conventional loan markets remain tight because of the credit crunch - many businesses have trouble in refinancing their operations by using retail banks so they have turned to the bond market. Many businesses want to lock-up their borrowing for longer period of time by issuing long-dated bonds. See this Financial Times presentation. Rising bond prices: The bond markets have been a good hedge during the recent financial crisis - between June 2008 and March 2009, a period in which the FTSE 100 fell by 36pc, the value of a 10-year UK government bond rose by more than 20pc. Bond prices have been boosted by central bank purchases of govt debt (see below) and also by Asian central banks using their growing reserves of foreign currency to buy bonds of overseas government and companies (e.g. China purchasing US Treasury debt). Another factor behind high demand for bonds has been new capital rules designed to boost commercial banks' liquidity. Record low interest rates: o Lenders: Interest rates on savings and other investment accounts have fallen sharply. Investors are turning to the bond market for the prospect of higher returns and there is a renewed investor appetite for higher risk /higher yield bond issues o Borrowers: The current low interest rate environment is an opportunity for businesses to raise fresh long-term finance at low cost - an alternative to issuing equity e.g. through a rights issue Mergers and takeovers - companies looking to make acquisitions may favour the bond market as a way of getting bridging-loans to fund takeover bids Budget deficits: Many governments are running huge fiscal deficits and must borrow billions every year to cover their spending. The UK budget deficit for 2009-10 is forecast to be over £170bn (more than 12% of GDP) and the Gilt Issue Office must issue more than £200bn of new government bonds to cover the deficit. The Bank of England has been involved in purchasing up to £200bn of bonds (mainly government gilts) through the quantitative easing policy. This demand has increased bond prices and depressed bond yields - at least initially. Risks from the boom in bond issues Rise in corporate sector debt which might become increasingly difficult to service There are risks of a boom in issue of junk bonds (higher yields / higher risk loans) especially if there is a bubble in the bond market) Increase in public sector debt from the fiscal deficits (the result of recession and also deliberate fiscal policy stimulus to depressed economies) Growing incentive for governments to inflate their way out of the problem of debt repayment (higher inflation erodes the real value of fixed interest bonds) Risk of sovereign debt default from the most indebted governments Some countries have already had their credit ratings downgraded and this will cause a rise in government bond yields which makes it more expensive to finance budget deficits o Dubai World - suspended repayments on a $3.5bn (£2.1bn) Islamic bond - eventually bailed out by Abu Dhabi o Greece's fiscal crisis - Newsnight video on the credit rating downgrade o Ukraine - forced into an emergency loan from the IMF (Dec 2009) o Other EU countries have very higher fiscal deficits - namely Ireland, Spain and Portugal o Iceland - government forced to take our $7bn of emergency financing from the International Monetary Fund and other Nordic countries UK still has an AAA credit rating - but should it lose this AAA rating or even be put on "negative watch", the country's interest bill would soar – putting further strain on the economy. This article asks if government debt is really that high? This article asks if government debt is really that high? The big risk is a sharp and sustained fall in the demand for bonds e.g. caused by evidence of rising inflation in the world economy. Falling demand will cause bond prices to fall and interest rates on bonds to rise. This will lead to a steep increase in the debt-servicing costs of governments and businesses threatening the economic recovery. Risks of sovereign debt default and capital flight In normal times government-issued bonds are regarded as lower risk than the loans issued by corporates but this seems to be changing as the bond markets have become increasingly concerned about the scale of public sector debt owed by national governments. Worries over sovereign debt default might cause capital flight from countries affected - putting sharp downward pressure on exchange rates. For example capital flight in the UK would cause sterling to fall, inflation to rise and make it much more expensive for the UK government to fund and finance its huge fiscal deficit. This would put extra pressure on the government to introduce fiscal austerity measures to bring the deficit under control. The Bank of England may also feel forced to hike policy interest rates to shore up confidence in monetary policy and stabilize the currency, threatening the fragile economic recovery. See this Financial Times article on the "spectre of sovereign default returns to the rich world." The UK economy has an enormous amount of public and private sector debt (combined) - British private and public debt is now 449 per cent of GDP - up from 350 per cent at the start of the decade. When interest rates are low the cost of servicing the debt may appear manageable. But this eye-watering level of unpaid debt is likely to be a major constraint on the sustainability and durability of any economic recovery in 2010 and beyond. That said the UK government has never failed to make interest payments or repay bonds as they fall due