Asia-Pacific

11 August 2011 Last updated at 02:34 GMT

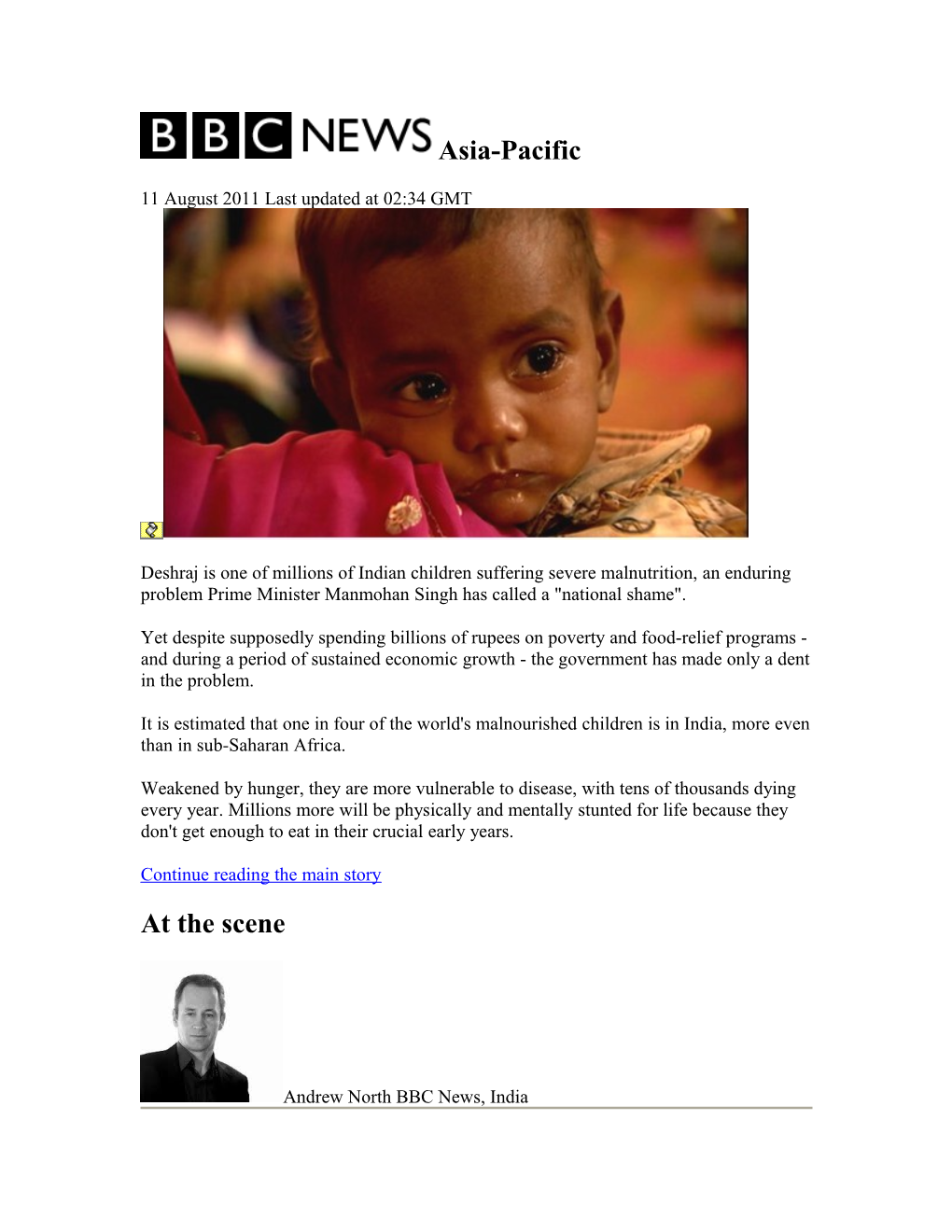

Deshraj is one of millions of Indian children suffering severe malnutrition, an enduring problem Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has called a "national shame".

Yet despite supposedly spending billions of rupees on poverty and food-relief programs - and during a period of sustained economic growth - the government has made only a dent in the problem.

It is estimated that one in four of the world's malnourished children is in India, more even than in sub-Saharan Africa.

Weakened by hunger, they are more vulnerable to disease, with tens of thousands dying every year. Millions more will be physically and mentally stunted for life because they don't get enough to eat in their crucial early years.

Continue reading the main story At the scene

Andrew North BBC News, India India has fallen in child development rankings, putting it behind poorer countries such as neighboring Bangladesh or the Democratic Republic of Congo, according to a new study by the Save the Children charity.

So when UK Prime Minister David Cameron hosts a summit this weekend on child malnutrition worldwide, India is one of the countries of greatest concern.

Yet this is hardly a new problem. India has been arguing over what to do about hunger and the poverty that underpins it for years - while its farms produce ever more food.

Left to rot

Under pressure, India's ruling coalition introduced a Food Security bill last year, supposed to enshrine the right to food for all. But no one is betting on when it will be passed amid the country's current political deadlock.

And some critics say there is still not enough political will to tackle the hunger problem.

Other more free-market oriented voices argue that the whole approach of subsidizing food and providing guarantees is wrong, simply creating a dependency culture.

Continue reading the main story

India has had yet another record harvest

What is really needed, suggests Arti Tivari from the nutrition centre, is for existing programmes to be "implemented properly and for people to do their jobs properly" - a polite way of saying that graft and corruption still infect the system.

It is a simple fact that no Indian child needs to go hungry.

A short drive from the nutrition centre is a massive grain warehouse, sacks of wheat piled nearly to the ceiling - part of a network of government food stores across the country.

For years now, India has been producing more food than it needs. Yet every year large quantities simply rot in these warehouses.

The situation is much better than a decade ago, insists government minister Sachin Pilot, whose portfolio is officially telecoms but who has become closely involved in food policy.

But he admits "it's unacceptable having so many children with pot bellies and stick legs".

India still has a very young population, and politicians often talk of this future "demographic dividend".

But there will not be much of a dividend if so many Indian children continue to be held back and stunted in their first years of life.