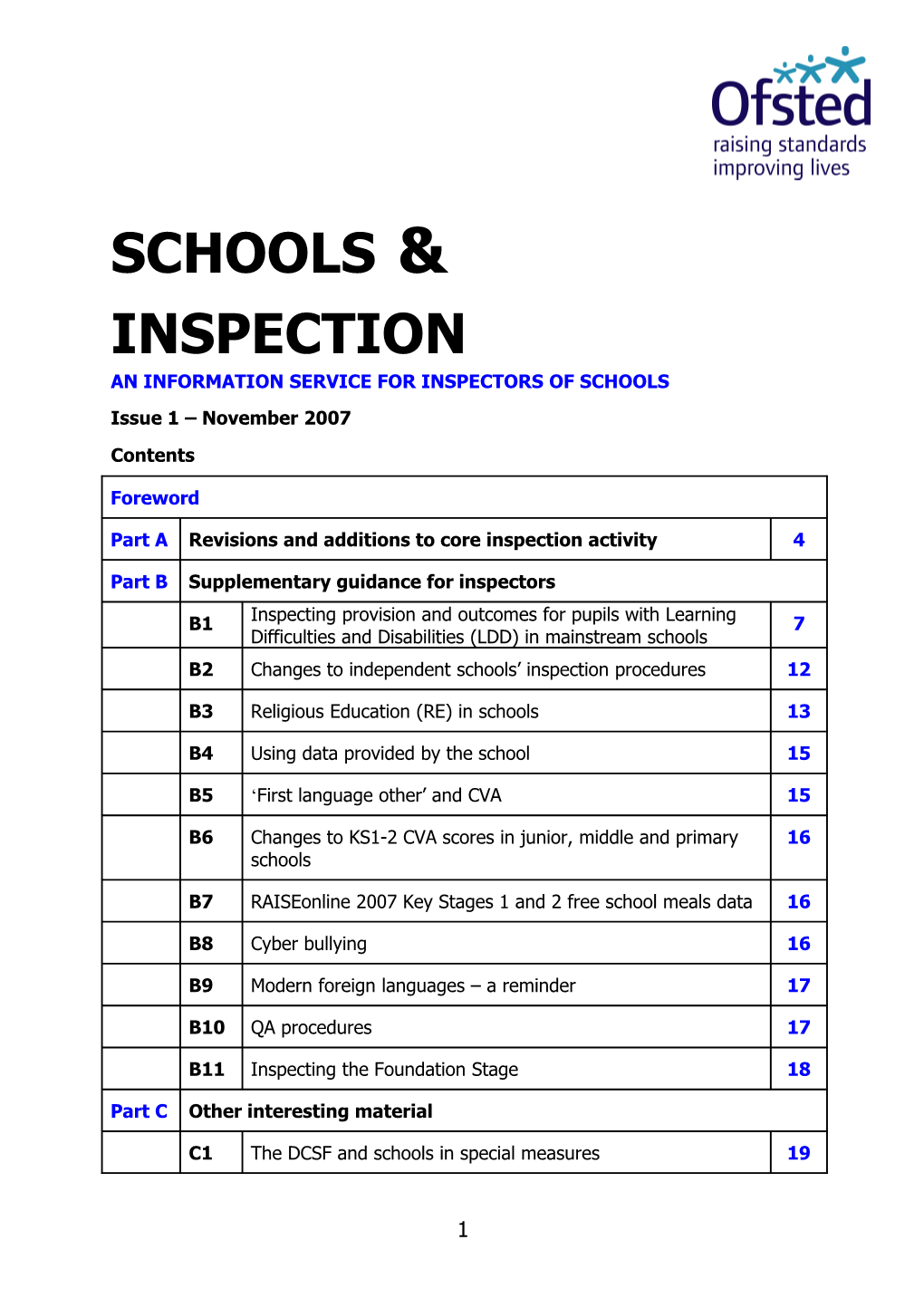

SCHOOLS & INSPECTION AN INFORMATION SERVICE FOR INSPECTORS OF SCHOOLS Issue 1 – November 2007 Contents

Foreword

Part A Revisions and additions to core inspection activity 4

Part B Supplementary guidance for inspectors

B1 Inspecting provision and outcomes for pupils with Learning 7 Difficulties and Disabilities (LDD) in mainstream schools B2 Changes to independent schools’ inspection procedures 12

B3 Religious Education (RE) in schools 13

B4 Using data provided by the school 15

B5 ‘First language other’ and CVA 15

B6 Changes to KS1-2 CVA scores in junior, middle and primary 16 schools

B7 RAISEonline 2007 Key Stages 1 and 2 free school meals data 16

B8 Cyber bullying 16

B9 Modern foreign languages – a reminder 17

B10 QA procedures 17

B11 Inspecting the Foundation Stage 18

Part C Other interesting material

C1 The DCSF and schools in special measures 19

1 C2 Attendance in secondary schools 19

C3 Attendance and religious observance 22

C4 Good practice in PRUs 23

C5 High performing specialist schools 26

C6 Revisions to school selection protocol 27

Part D Inspection Matters digest 28 OFSTED HELPLINE – 08456 404045 INSPECTION JUDGEMENT HOTLINE – 020 74215757

2 Welcome to issue 1 of Schools & Inspection which is the new name for Inspection Matters. This is the first edition compiled by Maureen Carroll and myself. The name change is a result of the wider inspection remit of the new Ofsted so that our readers will be clear that the focus of this journal is mainly on schools, with some additional material on initial teacher education.

This edition includes contributions from colleagues in Ofsted’s Curriculum and Dissemination Division, with a summary of their important findings on a number of significant issues related to schools and inspection. The guidance on inspecting provision and outcomes for pupils with learning difficulties and/or disabilities ensures that all inspectors can be up-to-date with current practice and considers how inspection evidence can be gathered efficiently. Additionally, a summary of Ofsted’s survey of secondary school attendance is complemented by a timely briefing on how inspectors should evaluate the effect of religious observance on pupils’ attendance.

The brief notices section contains details of changes to the inspection documents sent out in the September zip file and other general information for inspectors.

Suggestions for articles and written submissions for Schools & Inspection 2 should be sent to Maureen by 1 January 2007.

This is the (first and) last edition of Schools & Inspection for the year 2007 and the editorial team would like to wish all our readers an enjoyable Christmas.

Sean Harford HMI Editor Institutional Inspections and Frameworks Division

Getting in touch with us

Contact from readers is welcome:

articles can be discussed with Sean Harford, editor – [email protected] feedback, ideas for articles, contributions or issues that need to be addressed by inspectors can be sent to Maureen Carroll, assistant editor – [email protected]

Forthcoming issues of Schools & Inspection are planned for:

1. January 2008

2. March 2008

3. May 2008

3 Part A: Revisions and additions to core inspection activity

A1 Inspection documents zip file - September 2007

A few minor errors have been found in some of the guidance documents that are included in the September zip file. These are detailed below and, where appropriate, deletions to be made to current documents are shown in ‘strikethrough’ and additions are shown in ‘bold’, for ease of reference. Updated versions of these documents will be included in the next edition of the zip file, in January 2008.

Report writing guidance This document is obsolete and should be removed from the zip file. Guidance on report writing is included in Conducting the inspection.

Conducting the inspection Page 12, (Insufficient Evidence): ‘When the inspection team is clear that there is too little evidence available to reach a judgement, then a “0” “IE” may be entered in the Inspection Judgement Form cells for Personal Development and Well-Being, Teaching and Learning, and Care, Guidance and Support.

Page 21, bullet point at the top of the page: ‘Detailed guidance on inspecting attendance was given in Inspection Matters 8, May 2006 is given in the separate guidance document, ‘Inspecting attendance.’

Page 33, bullet point 9: ‘For all other schools, once there has been a first edit of the report and the letter, they should be sent to the lead inspector who incorporates necessary changes and sends them to the RISP, who then sends them to the school to enable a check for factual accuracy to be made.’

Page 37, right-hand side column of the table, last sentence of the first paragraph: ‘Write a full report with side sub headings.’

Using the evaluation schedule Page 4, amend second (non-tabulated) paragraph to: ‘A school whose effectiveness is clearly declining so that it is at risk of providing an inadequate education is likely to be judged to have inadequate capacity to improve and; it is therefore likely to be judged to be ineffective overall, even though it may still be providing an unacceptable standard of education at the time of the inspection.’

Framework for the inspection of schools

Page 14, section 45: ‘Parents are the main audience for the report; a brief letter to pupils giving the main findings of the inspection should be provided as an annex to the report. This should be addressed to the school council and should be written in language that is accessible to the majority of the pupils. HMCI expects schools to ensure that all pupils are made aware of the findings of the inspection. 4 Supplementary Guidance for Inspecting School Sixth Forms Summary Page 2: The words ‘and efficiency’ should be removed from the paragraphs relating to ‘Effectiveness and efficiency’.

Page 3, paragraph should read: ‘When the inspection team is clear that there is too little evidence available to reach a judgement, then an ‘IE’ may be entered in the Inspection Judgement Form cells for Personal Development and Well-Being, Teaching and Learning, and/or Care, Guidance and Support.’

Foundation Stage section of report template The new section 5 report template has a paragraph which requires the LI to grade the ‘Effectiveness of the Foundation Stage’ where relevant. Clarification has been sought for nursery school inspections, as the Foundation Stage is covered in the overall effectiveness section of the report. If the ‘Effectiveness of the Foundation Stage’ section is left blank it would indicate that the school does not provide the Foundation Stage, which would be incorrect. If the section is removed completely the report dataset would fail.

IIF will arrange for the datachecker to be upgraded but this will not be until autumn 2008.

To address this issue in the meantime we suggest the following sentence be inserted into this section of the report:

‘As a nursery school, the Foundation Stage is completely covered by the Overall Effectiveness section’.

A further question has arisen about the use of capital initials for the Foundation Stage. In line with Ofsted’s style guide, upper case initials should be used throughout the report, including in the title for the ‘Effectiveness of the Foundation Stage’. Until the report template can be amended for January, please change the title of this section appropriately.

A2 Inspection Matters digest

The Inspection Matters digest became increasingly long with each edition. Therefore, we have decided to provide links to the main digest on the Intranet and the Ofsted website in Schools & Inspection. See Part D of this edition for links to the current digest.

A3 Lessons learned in Special Measures schools

If you are taking, or have ever taken, a school through the SM monitoring process then please read on…..

5 With a view to sharing good practice, supporting HMI and AI in their monitoring of SM schools and celebrating the impact that such visits have on schools, we have embarked on a 'lessons learned' project and I write to enlist your help please.

The aim is to compile a document of examples from schools where specific actions have led to significant improvement in the various areas which we report upon.

Staff in Special Measures schools work exceptionally hard and often innovatively in order to improve their schools and it will be really good to capture some of this work to share with others.

We hope to collate about 20 short case studies (maximum 2 sides), each covering different phases and types of school and under the usual reporting headings of A&S, PD &WB, QoP, L&M.

If you have an example of good practice please contact: [email protected]

Thank you in anticipation

Ann Talboys

A4 RAISEonline – access by Diocesan Boards

We would like to draw inspectors’ attention to the fact that it is not possible currently for Diocesan Boards to access directly the performance and assessment data in RAISEonline.

A5 G3 statement in reports

Inspection Matters 11 provided the standard wording to be included in the overall effectiveness section of an inspection report when a school is judged satisfactory. We have reviewed the positioning of the statement in the inspection report: it should now follow directly the section ‘What the school should do to improve further’.

A6 Significant changes to aspects of a school’s work since its last inspection

Inspectors should explain clearly in the section 5 report any apparently stark differences in the main grades from one inspection to the next. This is to ensure that users are clear about aspects of a school’s work that change significantly between inspections. It is also to ensure that users do not confuse such changes with a lack of consistency in judgements. This is particularly important when inspections are more frequent than the statutory maximum, for example, when a school has been issued with a notice to improve.

6 Part B: Supplementary guidance for inspectors

B1 Inspecting provision and outcomes for pupils with learning difficulties and disabilities (LDD) in mainstream schools

Status: this article is supplementary guidance, providing background understanding for inspectors about how to inspect this area.

Changes to the statutory frameworks and guidance covering provision for pupils with LDD have been extensive over the last three years. Ofsted has conducted a number of surveys which identify good practice and this article is designed to:

ensure all inspectors are up-to-date with current practice consider how inspection evidence can be gathered efficiently.

The Statutory Framework

Definitions

The Children Act 1989, the Disability Discrimination Act 2005 and Section 312 of the Education Act 1996 define the duties and responsibilities for pupils with LDD. In addition, the SEN Code of Practice 2002 and the National Curriculum Inclusion Statement provide important guidance as to how these duties should be carried out.

The term LDD covers a very wide range of pupils. Schools are asked to categorise their pupils with LDD into four groups based on the SEN Code of Practice.

They are:

A. Cognition and Learning Needs ← Specific Learning Difficulty (SpLD) ← Moderate Learning Difficulty (MLD) ← Severe Learning Difficulty (SLD) ← Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulty (PMLD) B. Behaviour, Emotional and Social Development Needs ← Behaviour, Emotional and Social Difficulty (BESD) C. Communication and Interaction Needs ← Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN) ← Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) D. Sensory and/or Physical Needs ← Visual Impairment (VI) ← Hearing Impairment (HI) ← Multi-Sensory Impairment (MSI) ← Physical Disability (PD)

7 The Every Child Matters Framework uses the term ‘pupils with learning difficulties and disabilities’ rather than ‘Pupils with Special Educational Needs’ (SEN).

The term LDD, agreed with the DCSF, is used across the professional boundaries between education, health and social services from 0-19.

LDD is used to refer to individuals or groups of learners who have either a learning difficulty in relation to acquiring new skills or who learn at a different rate to the majority of their peers. All pupils with learning difficulties have disabilities as defined in the Disability Discrimination Act 2005. However, some pupils have disabilities under this Act but no learning difficulties, for example, some with diabetes, and sensory or physical impairments.

It is important to note that the interpretation of different groups identified by the code varies between schools and local authorities.

Reporting

Where there are significant groups of pupils with LDD referred to in the description of the school, a judgement about their progress should be explicit in the report. It is best to be as specific as possible and avoid general terms like LDD. The following examples illustrate this point:

‘Pupils receiving additional literacy support in Year 7 make good progress’ ‘Teaching assistants are usually effective in ensuring that pupils can participate fully in class’ ‘Pupils with statements of special educational need make better progress than other pupils with significant needs because they receive more effective specialist teaching’.

A judgement about the effectiveness of any additional provision should be included in the overall effectiveness section of the report. This should be based on the outcomes for the learners. Whenever there is a discrepancy between the outcomes for learners in resourced provision and other learners in the school, explain these fully, indicating the reasons.

Standards and achievement

A clear statement about the achievements and outcomes for pupils with LDD should be made, especially when the grade is different from that for other learners. Avoid a general statement and make a judgement specific to the learners to which it applies (refer to comment above).

RAISEonline provides information about the progress different groups make. The CVA information about the progress of pupils with LDD can be a helpful starting point but should be used with great caution. Numbers of these pupils are small by definition and SEN data (LDD) is used as a variable in the CVA formula. So for example, a school could identify more pupils in their SEN list and thus increase their CVA score. Pupils should only be placed on the SEN list if the school intends to make additional or different provision for them. If the inspection team are concerned that 8 the number of pupils identified has been artificially increased, the provision should be investigated further. There is little point in having large numbers on the list who do not receive enhanced provision.

For all age groups including post-16, it is not usually possible to establish trends in achievements simply by comparison of the number or range of accredited awards year by year, because the number of learners in a year group may be small and their needs vary sharply from year to year.

If the initial data indicates that pupils with LDD are not doing as well as they should in specific subjects compared to the progress of other pupils, the following trails can be useful in addition to the school’s own evaluation:

Investigate the quality of literacy intervention programmes. Most good literacy interventions result in improvements in reading age scores of about twice the expected gain. For example, a pupil with a reading age score of 10 years should have a reading age of 12 after one year of good intervention. This information is the basis of the National Strategies guidance.1 SENCOs usually have easy access to this information and it is a good indicator of progress.

Consider the quality of teaching in the lower sets or groups. Teaching assistants may be doing too much of the work for the pupils, the groupings may not be suitable or the work may not be sufficiently challenging.

Consider whether pupils with BESD are appropriately placed in teaching sets. They should be placed according to their attainment and academic potential, not placed in lower sets because they do not conform behaviourally.

Look at the books of a sample of pupils with LDD to get an understanding of how rapid progress is. Is there a significant variability across subjects, year groups or teachers?

In mainstream schools where pupils are working towards Level 1, they should be assessed by teachers using P-Scale data. Where there is little data available prior to the inspection about the progress pupils make, the school’s own analysis needs to be thoroughly interrogated. (Setting Targets for pupils with SEN HMI 751)

When evaluating the progress of pupils with LDD, keep in mind that local authorities often provide comparative data and the most effective schools can describe what they mean by good progress for different groups; for example, the number of sub- levels per year or 1 p-level per key stage. It is important to evaluate whether there is sufficient ambition in the targets set for pupils with LDD as well as the extent to which the targets are met. Inspectors should consider whether these expectations are high enough. There are a number of tools in regular use in schools to assist with the tracking of progress for pupils who make very small steps in their learning. The most commonly used are PIVATS (http://www.teachers.tv/download/1404/11770/redirect), B squared (http://www.bsquared.co.uk/index.php), BARE and Equals (http://www.equals.co.uk).

1 What works for children with literacy difficulties? The effectiveness of intervention schemes by Greg Brooks is published by the Department for Education and Skills (reference RR380). ISBN 1 84185 830 7. 9 All these schemes provide some benchmarking data to assist schools in comparing the progress of pupils.

You may find it helpful to refer to the criteria at the back of the publication: Special Educational Needs and Disability: Towards Inclusive Schools (HMI 2276).

Personal development

The way schools manage pupils with the most difficult behaviour reveals much about their ethos and approach to equality and diversity. Pupils with BESD require robust arrangements for personal and social development. They respond particularly well to help with their friendships and resolving conflicts, and to having one identified adult to whom they can talk. The impact of other staff, for example learning mentors, should also be noted. It is particularly important to explore the way certain groups of pupils are represented in the exclusion figures and an analysis of attendance data can be revealing. Pupils with LDD are often over-represented in the proportion of pupils excluded from school. This can then usefully lead to a case study approach early on in the inspection. For example, inspectors can look at the provision for a sample of pupils who have been excluded in the past.

Quality of provision

Teaching and learning

The number of teaching assistants employed in schools has risen dramatically over the last four years. Last year Ofsted reported that:

‘Pupils in mainstream schools where support from teaching assistants was the main type of provision were less likely to make good academic progress than those who had access to specialist teaching in those schools.

Teaching assistants who provided good support had often received high quality training and had relevant qualifications. Teaching assistants provided valuable support, and many were undertaking difficult roles, but this was not a substitute for focused, highly skilled teaching.’

Teaching assistants are often very good at adapting materials so that the pupils can engage with the lesson. However, the work the pupils are doing should be overseen closely by a teacher to ensure the next step in learning is carefully planned. It can be the case that emphasis is too often on access rather than progress.

The Curriculum

Schools may adapt and modify the National Curriculum so that it better meets the needs of individual learners. Schools do not need to formally disapply pupils where such adaptations are made. The flexibility in the curriculum exists for all age groups not just for pupils in Key Stage 4. Nevertheless, all pupils with LDD are entitled to a broad, balanced and relevant curriculum including the National Curriculum.

10 There are many ways of organising the curriculum to best meet the needs of all learners. Pupils are withdrawn from class most commonly for booster work, literacy, anger management, social skills training, physiotherapy, speech and language therapy and counselling. This can result in an adapted curriculum. Inspectors must recognise that there is limited time in the school day and pupils may miss some lessons in order to have their needs met. However, this provision should not be unduly disruptive and suitable arrangements should be in place to ensure the pupils’ curriculum is coherent. They should not miss key lessons and then be expected to catch up with no arrangements to assist this process. Additional intervention should not consistently prevent pupils from accessing favoured subjects or where they have real strengths.

Inspectors need to use their professional judgement to assess whether or not the curriculum is broad, balanced, differentiated and relevant. Attendance can be an indicator of curriculum relevance. It is not sufficient to just provide alternative accredited courses for pupils at Key Stage 4. The qualifications should extend the choices open to pupils in the future.

Care, Guidance and Support

The Code of Practice does not require schools to write Individual Education Plans (IEPs). Systems and procedures had become overly bureaucratic and there was limited impact on the outcomes for pupils. Nationally, standards for these pupils have remained static for some years even though standards were rising for most other groups. Local Authorities and the DCSF have been working with schools to develop alternative, more streamlined paperwork which still meets the statutory duties and provides suitable evidence for additional funding. It is not uncommon to find a system called ‘provision maps’ which have replaced IEPs completely in some schools.

A provision map describes all the provision available in or to the school. It can be a very useful document to scrutinise on an inspection as it can reveal the extent of the provision for different groups. So for example, if an inspector is concerned about literacy in the school as a result of another inspection activity, it can be useful to ask for the provision map to see how extensive the arrangements are to address the issue.

Where IEPs are in use they are often unhelpful to explore in depth on inspection. It is difficult to evaluate how challenging the targets are and therefore conclusions cannot be drawn about how much progress has been made. Pupils with LDD should have academic targets set alongside all the other pupils rather than through a separate system. These targets can be evaluated in the same way as for everyone else.

The evaluation of behaviour management arrangements is particularly important in enhanced resourced provision. The restraint and incident books may need careful examination alongside other evidence, as some pupils may not be present on the day of inspection. These should be bound books with each incident allocated a specific number. Care should be taken to check there is not an excessive use of physical intervention (also sometimes referred to as ‘positive handling’). Where physical intervention is used it is important to ascertain whether staff have received 11 appropriate training. Some courses have been accredited by the DCSF. The number and range of recorded incidents is also an important indicator of how successfully schools are managing very challenging behaviour.

B2 Changes to independent schools inspection procedures

1. Standard 4 – suitability of proprietor and staff

Inspectors should note that the templates for ROIEJ, ROMES for new registrations, general use and academies, SIEF, and self audit checklist have been amended to allow a ‘not applicable’ answer to the questions in regulations 4(2)(c), 4(2)(e), 4A (1-8), 4B (4 and 5), 4C (4 and 5). These all relate to the use of supply staff.

The ROIEJ has been amended so that inspectors are no longer required to record the number of teachers in special schools with QTS.

2. Safeguarding

Inspectors should note the following guidance:

When a safeguarding issue has been raised during an inspection but has not been resolved through CIE by its conclusion (which is likely to be the case), a footnote should be added to the welfare, health and safety section of the inspection report. For technical reasons, inspectors should first add the sentence below to the main body of the text in the welfare, health and safety section of the report so that it can be transcribed to a footnote later. The sentence should be separated from the main body of the text to ensure that it is clear to the reader:

‘Concerns raised by some pupils/a pupil/some parents/one parent* during the inspection are being examined by the appropriate bodies’.

* delete as applicable

3. Building Bulletin 77

Please note that this document was revised in 2005 and is on the DCSF website. This revised version will be put into the next zip file ‘useful references’ we send out, which is planned for January 2008.

12 B3 Religious Education (RE) in schools

Status: this article is supplementary guidance, providing background understanding for inspectors about how to inspect this area.

What does the law require?

RE should be provided as part of the basic curriculum for all registered pupils attending a maintained school. Parents have the right to withdraw their children from all or part of RE, and are not obliged to state their reasons for withdrawal. The 1998 School Standards and Framework Act (the 1998 Act) defined new categories of maintained schools; the rules about the provision of RE differ in some categories, as follows:

Community Schools, including some of the old 'County' schools. RE should be taught according to the Agreed Syllabus of the LA. Foundation Schools, including some of the old 'County' schools and old 'Voluntary Controlled' schools which were grant maintained. RE is taught according to the local Agreed Syllabus, unless the schools are of a religious character, in which case their RE is characterised by their Trust Deed. Voluntary Aided schools are those schools originally founded by voluntary bodies, but aided from public funds. RE should be taught according to their Trust Deed. Voluntary Controlled schools were originally founded by voluntary bodies, but are now controlled and entirely funded by the LA. RE should be taught according to the local Agreed Syllabus, but parents may request that RE should be provided in accordance with the Trust Deed. Special schools should provide RE for all their pupils as far as practicable, according to the status of the school. City Technology Colleges are independent schools; however, as a condition of grant, they are required to make provision for RE which is broadly in line with community schools. Academies are independent schools. Apart from the expectation that a broad and balanced curriculum will be provided, there is no statutory requirement for RE. 'Faith' Academies must consider all applications for places, according to the DCSF Code of Practice, but preference may be given to applicants of the particular faith. Schools with sixth forms must provide RE for all pupils in the sixth form in accordance with the requirements of the Agreed Syllabus. Sixth Form Colleges and Further Education Colleges should provide RE for all students who wish to receive it.

How does the Agreed Syllabus fit in?

RE is not part of the National Curriculum. Instead, it is locally determined: under the 1988 Act each LA is required to establish a Standing Advisory Council for Religious Education (SACRE) to advise the authority and its teachers on matters concerning RE. It also has a duty to convene an occasional group called an Agreed Syllabus Conference (ASC), which produces the local Agreed Syllabus from which teachers 13 devise schemes of work and arrange the assessment of pupils' learning. Every LA must review its Agreed Syllabus every five years.

In October 2004, the then DfES, together with the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA), published a Non-statutory national framework for religious education after extensive consultation. The document is primarily for the SACREs and ASCs in each LA but is influential as LAs review their local syllabuses, new resources are prepared and published and those involved in curriculum development plan their work.

What should be the time allocation for RE?

There are no prescribed allocations of time for RE. When Lord Dearing produced his final report into The National Curriculum and its Assessment (1993) he made some recommendations which assume appropriate time allowances for RE. For practical purposes these are widely recognised as 'markers'; the more so now in that Ofsted inspection procedures have no requirement to report on time allocation in RE. These are:

Key Stage 1 36 hours per year Key Stages 2 and 3 45 hours per year Key Stage 4 5% of total curriculum time

Implications for inspectors:

The following list is given to support inspectors who have concerns about RE, for example when evaluating the curriculum, but is not intended as an inspection checklist: Check the status of the school against the guidance above to be sure how the legal requirements for RE apply. Remember in most schools (apart from Voluntary Aided schools and academies), meeting statutory requirements means securing provision on the basis of the locally Agreed Syllabus. In secondary schools, there must be provision for all pupils at Key Stage 4, whether they are taking GCSE or not. If core RE is part of some kind of PSHCE provision, it must be identifiable and MUST cover what is required by the Agreed Syllabus. If, due to curriculum blocking, RE provision is not offered in a particular half term or even year, the inspectors should ensure that there is a full entitlement for RE planned over the key stage. The Agreed Syllabus will include details of the requirements for RE in schools with sixth forms. In most cases these will be very flexible recommending, for example, the use of focus days on themes related to religious, philosophical, moral and social issues

14 When should failure to meet statutory requirements become a reporting issue?

If a school is clearly failing to meet both the letter and spirit of the law then it should be reported in the text. For example, if a significant proportion of pupils do not receive any RE at Key Stage 4 this should be reported as a failure to meet statutory requirements. Such a failure does not automatically result in a grade 4 judgement for curriculum or elsewhere, but should be identified as an area for improvement. The right of withdrawal should be exercised independently by parents. It is NOT appropriate for schools to encourage or invite parents to withdraw their child from RE in order to offer some alternative learning such as booster classes in literacy. If this is happening, it should be reported as a failure to meet statutory requirements. However, if for some reason specific groups of pupils are not receiving their full entitlement to RE because they are partly withdrawn to engage in alternative activities such as a college based work-related programme, the inspection team will need to come to a balanced judgement about whether this is serious enough to include in the report.

B4 Using data provided by the school

Recent training and guidance have further emphasised the need for inspectors to consider fully achievement and attainment data provided by schools before or during the inspection. Some schools, for example middle schools, have asked that inspectors consider unvalidated data or the outcomes of internal assessments. For middle schools, inspectors should not rely only on Key Stage 1 tests as evidence for attainment on entry when pupils joined the school in Year 4 or Year 5, or fail to take due account of progress made in Years 7 and 8.

Inspectors should consider all reasonable information provided by the school, but should also ensure that the school understands the basis of the final inspection judgements. If schools provide an undigested mass of statistics, it is reasonable to ask them what analysis of the data tells them. A concise summary of what they believe the additional data are telling them is likely to reflect good self-evaluation. Inspectors should state explicitly, at least in feedback, the evidence on which they have based their judgements on standards and achievement, especially where this at variance with the school’s views.

B5 ‘First language other’ and CVA

Inspectors should be careful when interpreting the RAISEonline performance data for learners whose first language is not/is believed not to be English. RAISEonline does not group these learners based on their individual language needs and levels of proficiency. Consequently, in a given school, this group could include learners at the early stages of acquiring English along with advanced bilingual learners and those

15 with basic literacy needs. As with all performance data, this grouping of learners will be helpful in identifying lines of enquiry that inspectors may wish to pursue. However, the particular context and circumstances of the school and its learners need to be taken into account when making judgements about learners’ achievement.

B6 Changes to KS1-2 CVA scores in junior, middle and primary schools

This note was originally published as IIF Minute 24 but an amendment has been made to the second paragraph to reflect the situation when pupils change school at the start of Key Stage 2. Please see bold text below.

DCSF and Ofsted have made some adjustments to the mobility factors that help determine KS1–2 CVA scores. The adjustments generally have the effect of slightly increasing CVA scores in junior and middle schools and slightly decreasing those for all-through primary schools. They are incorporated in the 2007 release of RAISEonline.

The reason for the adjustment is that overall, pupils who change schools either during or at the start of Key Stage 2, make slightly less progress than those who do not. This factor is deemed to be outside of a school's control and so these pupils’ CVA scores are adjusted accordingly.

Therefore, please take great care analysing trends in CVA when inspecting junior, middle and primary schools. For example, when comparing results for 2007 with 2006. As always, it is very important that inspectors give appropriate weight to other evidence about the pupils’ progress, including that provided by the school and gathered through first-hand observation.

B7 RAISEonline 2007 Key Stages 1 and 2 free school meals data

You will be aware that 2007 data for Key Stages 1 and 2 were released through RAISEonline last month. Please note that the contextual data, giving the proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals in 2007 is based on all pupils in the school, including those in the Foundation Stage, rather than restricting to compulsory school age, as in previous years. Therefore, you may notice changes between 2006 and 2007 data that do not necessarily represent 'real' changes in the characteristics of pupils in the school. This will be corrected in January at the time of the Key Stage 3 release, making 2007 data consistent with previous years.

B8 Cyber bullying

When inspectors ask pupils about feeling safe in school and being bullied, pupils may not immediately interpret this as including ‘cyber bullying’. This term includes the use of text messaging, e-mails, social networking sites or calls from mobile phones. A 16 recent DCSF study showed that up to 34% of 12-15 year olds had experienced it. On 21 September Ed Balls, Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, launched a campaign to halt cyber bullying. Inspectors should ensure that explicit reference is made to cyber bullying when asking pupils about any bullying or harassment they may have experienced. It may also be appropriate to ask schools how they try to protect learners from this form of bullying.

B9 Modern languages reminder

Modern foreign languages (MFL) is statutory in Key Stage 3, an entitlement in Key Stage 4 and there is a national target of an entitlement for all pupils in Key Stage 2 by 2010. The current SEFs have prompts in section 5d for schools to evaluate progress towards language entitlement in Key Stage 2 and the 50%-90% take-up benchmarks in Key Stage 4. As part of evaluating the curriculum, inspectors may wish to be satisfied that the situation in MFL is clearly on the school’s agenda, and that it is making headway.

DCSF has just distributed to all secondary schools a new CD Rom entitled Languages in Key Stage 4, 10 Questions and Answers for School Leaders. In it there is a specific statement about inspection: ‘in schools where they judge it appropriate, both Ofsted and the SIP will be engaging with schools in relation to Key Stage 4 languages’. This is available to download or obtain at www.teachernet.gov.uk/publications (search using the reference DCSF -00669-2007).

B10 IIF QA procedures

We have made a slight revision to the guidance document ‘IIF QA procedures’. It is now available on our website, alongside the key guidance documents for section 5 inspections and will be included in the January 2008 zip file. This follows a recommendation from the Independent Complaints Adjudicator, that Ofsted should consider taking action to ensure that schools have ready access to written information on the role of the Quality Assurance Mentor (QAM). The recommendation particularly highlighted the potential for the QAM to relay immediately to the lead inspector any concerns raised, and so reduce the possibility of a later complaint.

The document has a new file title, The quality assurance of section 5 inspections by HMI, as well as two changes to the text, as follows (in bold):

5. Meet the headteacher. Discussion might include thoughts or concerns about the inspection, the conduct of the team, relationships with staff and pupils, the use made of the SEF, the school’s perception of the PIB, involvement and confidence in the inspection, and any impact in confirming or changing the school’s priorities. Encourage the headteacher to complete the School Inspection Survey questionnaire.

17 6. Meet the lead inspector. Discuss the conduct of the team, relationships with the school, the evidence base, the emerging findings, any concerns of the school, and any help that the lead inspector may require. If you have not had a chance to study the PIB, RAISEonline full report and SEF beforehand, do this as early as possible during the visit.

B11 Inspecting the Foundation Stage

New guidance for inspectors on Inspecting the Foundation Stage has been written; a copy is attached to this edition of Schools & Inspection as an annexe.

18 Part C: Other interesting material

C1 The DCSF and schools in special measures

Since 18 June 2007 the DCSF has stepped up its action with schools in special measures that are making inadequate progress. This is to increase the pressure on LAs to ensure that schools quickly make satisfactory or better progress and are removed from the category.

Using the powers from the Education and Inspections Act 2006, the DCSF is writing to the director of children’s services (DCS) of any LA where a school in special measures, on the first monitoring visit, receives a judgement of inadequate progress. The letter advises them that they have roughly one term to make satisfactory progress or the LA will face a Schedule 7 Direction that the Secretary of State regards the ‘case as urgent’. The use by the DCSF of this power means that the LA has to re-consider urgently its actions in relation to the school with a strong presumption of closure.

On the second and subsequent monitoring visits, two judgements are made. If the school has made inadequate progress since the first visit and inadequate progress since going into special measures, then a letter to the DCS will state that the LA has 10 days to outline, in a new statement of action, the action it now proposes to take. If the response is not to close the school then the LA must give clear and compelling reasons why the Secretary of State should not use his own powers to do so.

If on the second monitoring visit the school is judged to have made satisfactory progress since the last visit and inadequate progress since going into the category, the DCSF will write to the DCS and acknowledge this. However, they will also remind the LA that the school remains under scrutiny and if satisfactory progress since going into special measures is not made on the third visit then the Secretary of State may use his powers to declare ‘the case urgent’ and the procedures described above would be used.

The DCSF has made clear that before sending any of the above letters they will check the latest information on the school’s context and circumstances and carefully scrutinise the Ofsted monitoring letter so that their response is not disproportionate to the current situation. For example, the school may be waiting for permission to appoint an IEB. In the case of PRUs and special schools, there may not be an assumption of automatic closure because of the commitment to ensuring specialist provision for vulnerable pupils.

C2 Attendance in secondary schools

In September 2007 Ofsted published a leaflet and briefing note reporting the outcomes of a survey of attendance in secondary schools. The survey also assessed the impact of the National Strategy in promoting attendance.

19 Attendance in Secondary Schools leaflet (Reference no. 070014C): http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/assets/Internet_Content/Shared_Content/Files/2007/sept/ attendance_lft.pdf

Attendance in Secondary Schools briefing note (Reference no. 070014): http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/assets/Internet_Content/Shared_Content/Files/2007/sept/ attendance_bn.pdf

The outcomes from the survey usefully complement the document Inspecting attendance – guidance. As well as presenting some of the key messages from the survey some questions have been included in the text below which inspectors might find useful to consider if they have concerns about rates of absence in a secondary school.

Inspections of secondary schools in 2005/06 showed that there is a strong relationship between social deprivation, as indicated by free school meals (FSM), and lower rates of attendance. However, the data also shows that this trend can be bucked. A small number of schools in the highest FSM band have good or outstanding attendance. Although only a very small sample of schools, its does suggest that the level of eligibility for FSM is not a justification for low levels of attendance.

Strong and determined leadership is crucial to secure good attendance. In schools where this was evident: the importance of attendance was made clear to students, parents and staff education welfare officers were an integrated part of the school’s attendance team, operating flexibly and responsively to influence change and improvements roles were made clear but responsibilities for attendance were shared by staff and not just given to education welfare officers and attendance officers monitoring was carried out regularly, helped by electronic methods of gathering and analysing data.

Have senior leaders ensured that the responsibility for attendance is shared by all staff?

300 students were interviewed in the survey and the main reasons that all these students gave for their unauthorised absences were consistent. They emphasised: that some lessons were boring difficulties getting on with particular teachers difficulties catching up with work.

Many of the schools did not do enough to ensure that students caught up with the work they missed. Arrangements were seldom systematic or consistent. However, one school introduced formal arrangements for students who had missed work by enabling tutors and subject teachers to work together to prioritise a short ‘to do’ list. The student and tutor then discussed how and when the work would be completed.

20 How well does the school arrange catch up work for students who have been absent?

Many students whose attendance was marginally over 90% regarded this level of attendance as entirely acceptable. Since schools mainly focus their attention on students whose attendance is below this threshold, they may be inadvertently condoning relatively poor attendance. One school had revised the way it uses percentage figures in communicating with parents: it published the number of half- days missed, together with what this meant for their child. For example, 90% attendance meant 19 missed days in one year or approximately one month’s absence. Parents and students found this information more useful and, as a result, attendance rates overall had improved.

How effectively does the school challenge attendance at levels above 90% as well as below this?

Attendance rates have improved nationally since 2002/03. However, unauthorised absence has not shown the same level of improvement and practice in schools is inconsistent. One school may accept a reason for absence that another may not be prepared to condone. Legal sanctions, such as fixed penalty notices and prosecution, and telephoning student’s homes on the first day of absence have all been effective deterrents but they have not reached the most disaffected groups. Nevertheless, such sanctions send an important message to other students and their parents and are a useful deterrent. The systematic stepping up of responses was a consistent feature in schools which were resolving attendance problems successfully.

Does the school use an array of strategies to promote good attendance including challenges to parents and carers where necessary?

The DfES gave targeted schools general information about the effect of poor attendance on students’ achievements. Schools found this helpful and used it to make their attendance data relevant and useful for students. One school used data from the previous Year 11 to create a graph showing the relationship between their attendance and achievement. Staff showed the graph to all students in Key Stage 4 to demonstrate that the students who did best were those with the highest attendance rates. The students understood that this was real information about students they knew and this helped them see its importance.

Does the school do all it can to ensure that students are aware of the real connections between attendance and achievement?

At the time of the survey the National Strategy was working with identified schools because of high overall absence rates and/or high unauthorised absence. This work is in its third year and the DCSF is now working with 436 secondary schools to reduce levels of persistent absenteeism (those students absent for 20% or more of available sessions). A letter from Kevin Brennan MP, sent to all Directors of Children’s Services in August 2007, described the government’s expectations with regard to persistent absenteeism. Here is the link to the letter: letter from Kevin Brennan MP to Directors of Children's Services.

21 The Education (School Attendance Targets) (England) Regulations 2007 came into force on 1 September 2007. These regulations continue the requirement for all maintained schools to set a target for overall absence. Some schools will also be required to set targets for pupil groups whose absence exceeds a given threshold (e.g. ‘persistent absentees’).

Guidance for setting attendance targets (and other education performance targets) is contained in the DCSF Guidance to LAs in September 2007. Here is the link to the documents: http://www.standards.dcsf.gov.uk/ts/publications/list/

C3 Attendance and religious observance

Patterns of attendance in a school may be significantly affected by absences related to religious observance.

The dates of a number of major religious festivals move within the school calendar and patterns of pupil absence associated with such festivals can have a very significant impact on overall attendance figures. This year, for example, both Eid ul Fitr and Eid ul Adha, two major Muslim festivals, both fall within the autumn term while in previous years one or both might have fallen within school holidays.

The DCSF guidance is that absence due to religious festivals must be authorised by the school if the festival meets both of the following criteria:

it is a day set apart exclusively for religious observance it is set apart by the parents' religious body.

Schools should record absence due to religious observance using Code R. This means they can quantify such absence and disaggregate it from overall absence figures.

The impact of absence for religious observance can be significant. For example, in some Muslim communities Eid ul Fitr, at the end of the month of fasting, can be a two day celebration and Eid ul Adha, associated with the Muslim pilgrimage, can involve up to three days of celebrations. In addition, the month of Ramadan can result in a dip in attendance in primary schools on Fridays when mothers keep their younger children at home while the meal to celebrate the breaking of the fast is prepared.

What should inspectors do?

In schools with a very high proportion of affected pupils, inspectors should check with the school what the impact of the festivals has been on the pattern of absence and attendance figures. Schools should be in a position to disaggregate the absence due to religious observance (Coded R) from their overall attendance data. However, in coming to a judgement it may be important to have a conversation with the school about any patterns of absence related to religious observance which the school has not recorded using Code R, where for example, the pattern of absence relates to travel to visit the wider family. 22 C4 Good practice in PRUs

Ofsted’s recent report, Pupil referral units: establishing successful practice in pupil referral units and local authorities will provide help for inspectors when inspecting PRUs. Inspectors are advised to refer to the greyed out boxes in the text of the report as they capture key points about good practice:

Direction and purpose (p7) Curriculum (p10) Assessing and tracking progress (p11) Working with partners (p13) Local Authorities (p14) Continuum of provision (p16) Monitoring and evaluation (p18).

Judging Progress

When judging progress inspectors will need to recognise that the number of pupils on roll will probably be quite small and yet the range of abilities might be quite wide. This range could include pupils capable of attaining highly to those with significant learning difficulties and disabilities whose attainment might well be quite limited. The progress made by the pupils and their attainment will need to be obtained from the PRU’s tracking data, including any examination results, discussions with staff, observations of pupils at work and the work they produce. Professional judgement will need to be used when making judgements about progress as there is no RAISEonline for PRUs and other comparative data such as SATs and GCSE results are unlikely to be comprehensive.

Questions to ask to inform professional judgements include:

Have the staff agreed what they consider is good progress for individuals and even groups of pupils? Are the starting points for each pupil evident? How challenging are the targets for individuals and groups of pupils? Are all pupils making sufficient progress and if not why not?

Inspectors should take account of the core objectives of the PRU’s work. For instance, in a PRU providing for excluded pupils or those at risk of exclusion, the core work should give even more emphasis to ECM matters and notably specific improvements in the pupils’ attitudes, behaviour and/or attendance.

23 Judging Behaviour

Note: this section was previously published in October as part of IIF Minute 23.

Criteria for judging the standard of all learners’ behaviour were included for the first time in the September 2007 version of Using the evaluation schedule. Since their publication, some colleagues have asked about the use of the criteria in evaluating pupil referral units (PRUs) and special schools primarily for learners who present challenging behaviour.

In using the new criteria, inspectors should refer to the five bullet points listed on page 9 of Using the evaluation schedule. These identify the factors to consider when evaluating behaviour. They help to place the grade descriptors on page 11 in the context of the wide range of institutions we inspect, including PRUs and special schools. The grade descriptors, context, professional judgement and inspection evidence should all be used to decide on the most appropriate grade for behaviour in that institution. The key factors that need to be considered include the learners’ responses to the efforts of staff to manage and improve behaviour and the extent to which progress is affected, positively or negatively, by learners’ behaviour. In PRUs and in some types of special schools, inspectors should take account of pupils’ starting points when they arrived at the school and their improvement over time. However, regardless of the type of institution, if behaviour is sufficiently poor as to inhibit learners’ progress or well-being more than on very isolated occasions, it should be always judged inadequate. Where progress is judged to be at least satisfactory but there are concerns over behaviour, inspectors should consider how the learners’ behaviour is having an impact on learners’ outcomes and make their judgement accordingly.

In settings such as PRUs, evidence of individuals’ poor behaviour should not always lead to judgements of inadequate leadership and management. Many learners will have been placed there specifically because of their previous poor behaviour. Inspectors should consider factors such as how long the learners have been at the setting, whether strategies for improving individuals’ behaviour are securely in place, and whether there is evidence that the learners are responding to these strategies. In considering the effectiveness of leadership and management, inspectors will take into account the progress made in improving behaviour.

Full time Education

From September 2007 schools are required to provide full-time education from and including the sixth day of any period of fixed period exclusion of six days or longer. LAs are required to provide full-time education from the sixth day of a permanent exclusion; this replaces the present commitment to provide full-time education from the sixteenth day of a permanent exclusion.

1The DCSF’s view is that ordinarily suitable full-time education should equate with the number of hours of education the pupil would expect to receive in school (from 21 to 25 hours depending on the pupil’s age, as set out in DfES Circular 7/90: Management of the School Day).

24 ‘Full-time’ means offering supervised education or other activity equivalent to that offered by mainstream schools, as follows:

Key Stage 1 21 hours Key Stage 2 23.5 hours Key Stage 3 / 4 (Year 10) 24 hours Key Stage 4 (Year 11) 25 hours

Special Educational Needs and PRUs

An extract from: Guidance for Local Authorities and Schools - PRUs and Alternative Provision – (LEA 0024/2005), DfES 2005

4.28 The local authority is empowered (Section 319 of the Education Act 1996) to arrange for some or all of a child’s special educational provision to be made otherwise than at school. Such arrangements could include education in a pupil referral unit, home tuition or education that reflects key stage 4 flexibilities. However, if a pupil’s long-term needs cannot be met in a mainstream school, a special school rather than a PRU should be named on a statement of SEN.

4.29 Where a pupil with a statement of SEN is placed in a PRU or other form of Alternative Provision because a place in a mainstream or special school appropriate to meet the needs specified in the statement is not yet available, regular planning and review of the placement is essential, alongside steps to provide the necessary support.

Implications for inspectors:

Ofsted’s recent report on PRUs recommended that LAs follow the above guidelines. When inspecting a PRU inspectors should establish whether the PRU has any pupils on roll with a statement of SEN. If so, the following questions could be asked:

What is the long term plan for each of these pupils (NOTE: inspectors should ascertain the planned next step for all pupils in addition to those with statements) – mainstream school, special school, college? What is the timeframe? Have appropriate actions been taken to move towards this next step? How effectively and how regularly does the LA monitor the progress of each pupil with a statement (attendance at an annual review meeting would not be considered sufficiently regular or rigorous)? Whilst the inspection report will be focused on the PRU itself it has to be remembered that the LA has further responsibilities for those pupils with statements of educational needs and should be monitoring their provision and progress. How easily can the PRU gain support to help staff to meet the pupil’s needs (for example with challenging behaviour, learning difficulties)?

25 C5 High performing specialist schools (HPSS)

Author: Graham Pepper, DCSF

Status: this article is for information only (not part of Ofsted inspection guidance).

Inspectors will be aware of the curriculum specialisms in specialist schools but there are also additional options made available to High Performing Specialist Schools.

Training Schools Training Schools should demonstrate excellent practice across the range of teacher training activities, especially in initial teacher training and the continuing training and development of the whole school workforce. Successful Training Schools should be demonstrating the following, non-exhaustive, aspects:

Training School status contributes to the whole school ethos – creating opportunities for enthusiastic staff to innovate They develop rapidly as learning communities involving pupils, teachers, parents community and business organisations Development of clusters involving other schools which are less active in teacher development.

Training Schools are major providers of teacher training placements.

Raising Standards strand

This incorporates three programmes.

The Raising Achievement Transforming Learning Programme is designed to support schools with the potential to raise achievement. It seeks to combine immediate strategies that make a difference with longer term strategies that transform learning. It involves a ‘by schools for schools’, practitioner-led approach to school improvement, taking the risk out of innovation through building on current best practice. The programme enables schools to work together to find solutions and draws on the experience and expertise of mentor schools.

The Leading Edge Partnership Programme is designed to enable groups of schools to work together to improve learner outcomes at Key Stages 3 and 4, particularly amongst the lowest attaining learners. The programme is led by schools that are encouraged to develop innovative solutions to their own learning challenges. Partnerships are expected to share practice and learn from each other through nationally organised events. The number of schools in a partnership normally comprises between three and five schools with a HPSS school taking the lead.

The Youth Sport Trust (YST) School Leadership Programme seeks to raise learners’ achievement through the creation of leadership partnerships between HPSS schools and other specialist schools. The YST not only expects these partnerships

26 have an impact on pupil achievement but also on a range of local and national succession planning issues. The YST brokers school partnerships.

Vocational Second Specialism (VSS) High performing VSS specialist schools will be expected to champion vocational excellence by developing and delivering high quality vocational and work-related learning. They should take a leading role in collaborative provision across local partnerships which will involve other schools, colleges, centres of vocational excellence (COVEs), training providers, local businesses and employers. VSS schools will have a key role to play in driving up the numbers of young people achieving Level 2 qualifications, including functional English and mathematics, and increasing the proportion of young people staying on in education and training post-16. They will also have an important role to play in the development and introduction of the new specialised diplomas.

SEN specialism/Inclusion High performing specialist schools considering the SEN specialism and inclusion option are expected to focus upon one area from the Code of Practice, listed below. There is an expectation that schools will demonstrate clear commitment to inclusion and the ECM agenda and this will be shown to have a positive impact upon whole school improvement and benefit all students. There is an expectation that schools with the SEN specialism and inclusion option will work in partnership with neighbouring special schools and share expertise with both special and mainstream schools.

Schools selecting the SEN specialism and inclusion option will specialise in one of the four areas of the SEN Code of Practice:

. Cognition & Learning . Communication & Interaction . Behavioural, Emotional and Social Development . Sensory and/or Physical needs

C6 Revisions to school selection protocol

We have revised the Selecting schools for inspection protocol which deals with section 5 and section 8 inspections. In addition to the selection procedures for schools in normal circumstances, the protocol explains the frequency and timings for inspection of a range of different types of school, including academies, fresh start/collaborative restart schools, amalgamated schools and those that are in categories of concern.

By December 2007, all schools that were in section 10 (School Inspections Act 1996) legacy categories of concern at September 2005 will have been inspected under section 5 of the Education Act 2005. The protocol has been updated to reflect this and to update the guidance given to work programmers regarding the scheduling of section 8 and reduced tariff inspections.

The updated protocol will be posted on the internet. 27 Part D: Inspection Matters digest

Link to digest on Intranet http://intranet/NR/rdonlyres/3E2E3FE6-AD83-4CC9-A284- A7B1F1C300AD/0/inspectionMattersDigest.doc

Link to digest on Ofsted website http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications/20070039

28 Annex A

Inspecting the Foundation Stage

Guidance for inspectors November 2007

29 Contents

Introduction: the purpose of the guidance 3

An overview of the process 4

Section 1: Features of good practice 5

Section 2: Some pointers to inadequate provision 7

Appendix A: judgements on attainment on entry (AoE), attainment and/or progress 10

Appendix B: the Foundation Stage Profile 13

2 Inspecting the Foundation Stage

The purpose of this guidance

The purpose of this document is to supplement existing guidance. It should be read in conjunction with Conducting the inspection: guidance for inspectors of schools and Using the evaluation schedule: guidance for inspectors of schools. It aims to support inspectors in identifying good practice in the Foundation Stage (FS).

From September 2007, inspectors have been required to write a separate paragraph on the Foundation Stage (FS) in the report. In part, this is in preparation for September 2008 when the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) becomes statutory. The EYFS will replace the existing three documents Curriculum Guidance for the Foundation Stage, Birth to Three Matters and the National Standards for Under 8s Day Care and Childminding. Inspectors should be aware that schools may begin to make increasing use of EYFS documentation during the coming year in preparation for implementation.

The Early Learning Goal in Communication, Language and Literacy was changed from September 2007 to reflect the findings of the Rose Review2 into the teaching of early reading. The change is that children should: ‘hear and say sounds in words in the order in which they occur’. This replaces the original statement that children should: ‘hear and say initial and final sounds in words, and short vowel sounds within words’. Inspection Matters 15 contains an article on the teaching of early reading and the publication of the DCSF phonics programme ‘Letters and Sounds’.

Inspectors will be kept updated on further developments through Schools & Inspection.

2 Jim Rose, Independent review of the teaching of early reading: final report (0201-2006DOC-EN), DfES, 2006. 3 Inspecting the Foundation Stage

An overview of the process Getting started: before the inspection

As always, the self-evaluation form (SEF) is the starting point. Consider what the school says about the FS in each section of the SEF. Are there any contradictions between the sections that might raise a question to follow up, or evidence of strengths to be confirmed by the inspection? What evidence is there about the pupils’ attainment on entry or their subsequent progress? The pre-inspection briefing (PIB) should reflect any issues about the FS raised in the SEF. Look at the previous report and ensure any issues raised there are followed up, as necessary. Look at the Key Stage 1 results and any analysis of these in the SEF. Are there any issues here that might have a basis in the FS? For example, if results in mathematics are especially low you would want to track back to pupils’ earliest mathematical experiences, as well as those in Key Stage 1. As usual, plan appropriate trails and set up meetings with staff who can answer your questions.

During the inspection

Ensure sufficient time is devoted to the inspection of the FS. Inspection activities should include: observations of sessions/lessons in the FS, taking account of the issues you have raised in the PIB and assessing the personal development, welfare and safeguarding of the FS pupils; an analysis of the school’s information on attainment and progress in the FS; and discussions about the leadership and management of the FS. Guidance on judging attainment and progress, including analysing data from the Foundation Stage Profile (FSP) can be found at Annexes A and B; these are extracts from Guidance for inspectors on the use of school performance data. Additionally, this guidance is now available as an interactive training package. Contact Institutional Inspections and Frameworks, Ofsted, for more information. To help with pitching judgements, some features of good practice in the FS, including assessment, can be found in Section 1 of this document and some pointers about inadequate provision are in Section 2.

Writing the report

Your judgements on the overall effectiveness of the FS are reported in a separate section which follows the overall effectiveness section of the report. Report on the quality of the provision and outcomes for learners, explaining why things are as they are, clearly identifying any key strengths or weaknesses. Any key weakness in the FS should be brought forward as points for improvement for the whole school and reflected in the overall FS grade. Any significant strengths or weaknesses will have a proportionate impact on overall school grades in a

4 Inspecting the Foundation Stage

similar way to a weakness in a key stage might impact on overall Achievement and Standards grades. A length of around 200 words will normally be appropriate, depending on the context, size of provision and findings. This should allow for sufficient detail and exemplification about the FS to give parents a clear picture of provision, but particular strengths or weaknesses may require further detail.

Section 1: Features of good practice

Learning for young children should be ‘a rewarding and enjoyable experience in which they explore, investigate, discover, create, practise, rehearse, repeat, revise and consolidate their developing skills, knowledge, understanding and attitudes. During the Foundation Stage many of these aspects of learning are brought together through play and talking.’ (Curriculum Guidance for the Foundation Stage, QCA)

The following are features of good practice which may be of some support to inspectors in coming to judgements. This is by no means a definitive list and as always, inspectors should exercise professional judgement when coming to a decision about the overall effectiveness of the FS.

Learning and personal development: what to look for Inspectors will need to evaluate the achievement and standards of the learners as well as their personal development and well-being which are demonstrated by children: initiating activities, showing initiative and making decisions having time to explore ideas and interests in depth behaving well, feeling secure and becoming confident learners developing their concentration and ability to see activities through learning in different ways and at different rates making links in, and discussing their learning recognising that they have learned something new and ‘improved’ working co-operatively (for example, taking turns, sharing and discussing) taking responsibility (for example, tidying up, pouring the juice) following instructions and responding well to questions learning through movement and all their senses learning to accept each other’s differences.

Inspectors must judge how well knowledge, skills and understanding are achieved in the planned activities, such as those noted above.

Quality of Provision: what to look for Inspectors will evaluate what the school is doing to promote the outcomes considered in the previous section of this guidance. They will seek to identify: an inclusive approach that meets the diverse needs of all children high-quality care in a safe and secure environment well-planned and purposeful activities that engage and interest the children, and help to achieve an appropriate learning objective

5 Inspecting the Foundation Stage

‘continuous’ provision where progress is promoted through different areas of learning, including the effective use of the outdoor environment to extend all six areas of learning a good balance between children making purposeful choices about their activities which consolidate learning and adults directing what they do/ teaching specific skills appropriate use of the National Strategy materials adults modelling language well, to extend children’s speaking skills adults actively teaching ‘good’ behaviour (rather than policing) adults encouraging independence rather than doing things for children (for example, showing a child how to tie a shoelace rather than tying it) clear roles for and expectations of other adults working in the setting to ensure they add to the children’s learning experience good relationships with and involvement of parents/carers in their children’s learning.

Children develop rapidly in the early years: assessment should be based on observation which in turn informs the planning and provision. In the best practice, the observations will be carried out against clear criteria of outcomes. In coming to judgements about the effectiveness of assessment in guiding and supporting the children, inspectors should bear in mind the following:

Inspectors should not expect to see, nor recommend, a particular method of assessment or record keeping. Accredited baseline assessments are not statutory. However, staff should be able to demonstrate that they evaluate children’s starting points in order to identify next steps in learning and to evaluate their progress. Ongoing observations of child centred/initiated activities on post-it notes and/or notebooks are common but not the only method. Practitioners may keep individual records, records of achievement, annotated work samples, photographs, records of focused observations, observations of specific assessments and tick sheets. All these strategies have a place providing there is a purpose to them. Effective practitioners are likely to use the information they have to identify the next steps in children’s learning and to plan appropriate activities that will build on what children already know, understand and can do. The systems in place should be manageable, operated consistently by staff and used effectively. Staff should be able to explain their assessment and record keeping system to inspectors, show how it demonstrates the progress children are making and explain how they ensure children are appropriately challenged.

Inspectors should be aware of the National Assessment Agency guidance (see http://www.naa.org.uk/downloads/FSP_factsheet-_2007_Guidance_LA_Completing_Foundation_v042.pdf ) to schools and local authorities that assessment in the early years should be based on the collection of a range of evidence from a wide variety of sources. Additionally, the Early Years Foundation Stage advocates ‘look, listen and note’ as an integral part of the daily activities to help practitioners assess the progress children are making.

6 Inspecting the Foundation Stage

Leadership and management The FS leader (or Key Stage leader or headteacher depending on the size and management structure within the school): sets clear direction for developments within the FS with a strong focus on achievement, personal development and well-being has a clear vision about how the development of the FS is integral to the overall improvement in the school motivates staff and children and is a model of good practice is committed to professional development and workforce reform to ensure that all staff/assistants are valued and encouraged to improve their practice monitors and evaluates provision to identify strengths and areas for improvement promotes equality of opportunity, setting challenging targets and tackling discrimination so that all children make good progress ensures staff understand their roles and responsibilities in developing children’s learning and in sharing successful teaching strategies helps staff to work together to help all children make progress towards the early learning goals in each area of learning gathers and uses feedback from parents monitors the progress children are making towards the early learning goals, analysing the progress they make to identify where provision could be better has high expectations of the staff, children and their families has led and overseen clear improvements since the previous inspection contributes to the promotion of community cohesion ensures that the governing body is actively involved in the FS and contributes to improvement through its role as a critical friend.

Section 2: Some pointers towards inadequate provision

The presence of a single feature in the list below is unlikely to lead to a judgement that the FS is inadequate. However, a combination of features that result in important weaknesses in teaching and/or significant gaps in the provision that hamper children’s learning and personal development are likely to lead to that judgement. At worst, a general lack of care may compromise children’s health and safety. If FS leaders and senior managers do not give the staff an adequate sense of direction and show insufficient capacity to affect improvement, you must consider the impact of this on the overall judgement on the school.

Outcomes in learning and personal development It is essential that inspectors refer to Annexes A and B in coming to judgements about inadequate progress.

Learners in general, or a particular group of them, make inadequate progress in relation to the stepping stones and towards the early learning goals in one or more of the areas of learning. Children are not making sufficient progress in developing listening and speaking skills, making use of books or developing skills in writing, reading and the linking of sounds and letters. 7 Inspecting the Foundation Stage

Learning about numbers and counting, shape, space and measures and understanding of numbers is not promoted through practical activities. Children’s knowledge and understanding of the wider world is limited by a narrow range of experiences to investigate and explore their immediate and local environment, to encounter people, plants and creatures, and to use a variety of tools and range of materials. Children’s poor attitudes and/or unacceptable behaviour limit their achievements. This may be seen in low self esteem, lack of confidence and independence, poor concentration and effort, lack of sustained concentration characterised by flitting between activities, poor relationships, arguments over resources, or aggressive behaviour.