Return-to-Work Decisions of Mothers and the Well being of their Children

Raquel Bernal New York University

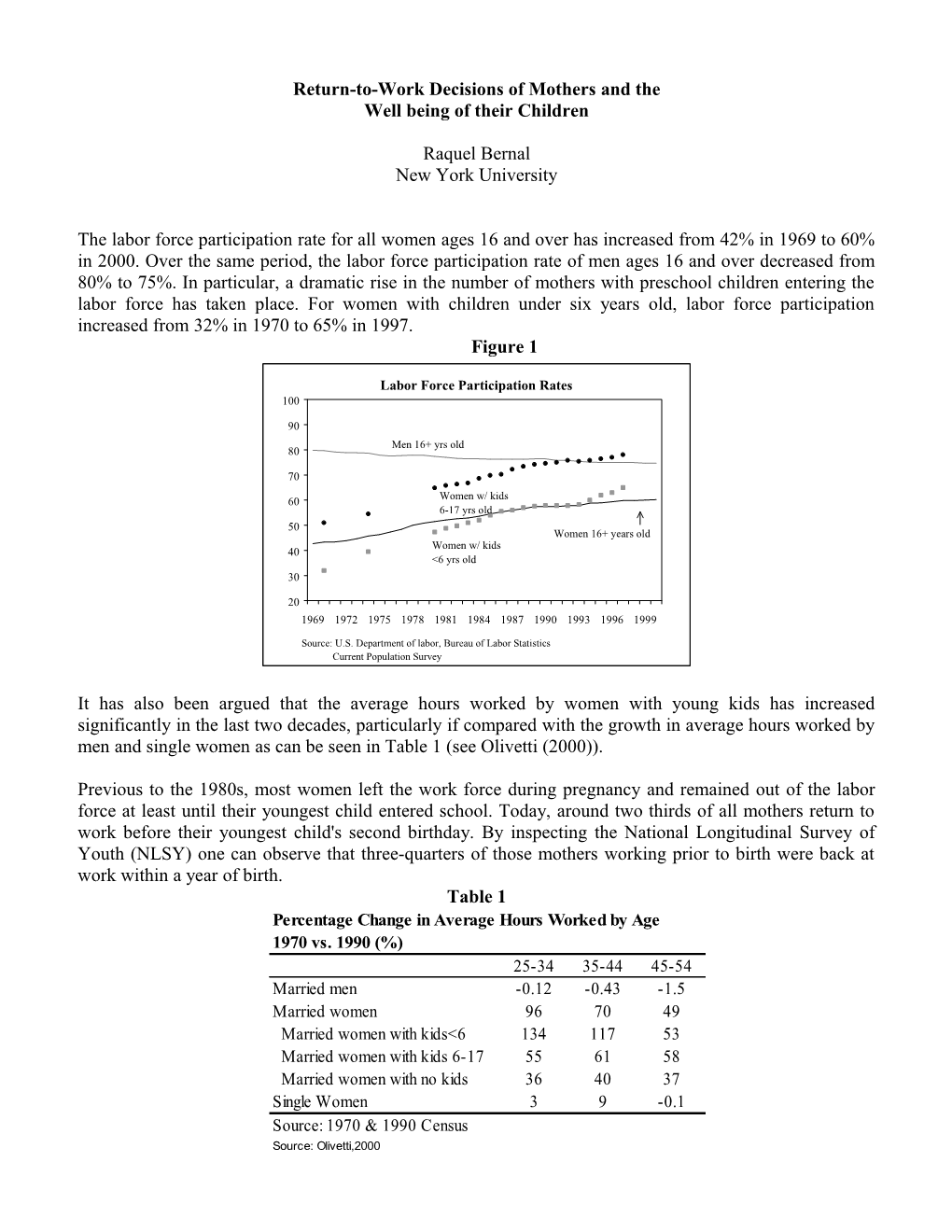

The labor force participation rate for all women ages 16 and over has increased from 42% in 1969 to 60% in 2000. Over the same period, the labor force participation rate of men ages 16 and over decreased from 80% to 75%. In particular, a dramatic rise in the number of mothers with preschool children entering the labor force has taken place. For women with children under six years old, labor force participation increased from 32% in 1970 to 65% in 1997. Figure 1

Labor Force Participation Rates 100

90 Men 16+ yrs old 80

70

60 Women w/ kids 6-17 yrs old 50 Women 16+ years old Women w/ kids 40 <6 yrs old 30

20 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999

Source: U.S. Department of labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey

It has also been argued that the average hours worked by women with young kids has increased significantly in the last two decades, particularly if compared with the growth in average hours worked by men and single women as can be seen in Table 1 (see Olivetti (2000)).

Previous to the 1980s, most women left the work force during pregnancy and remained out of the labor force at least until their youngest child entered school. Today, around two thirds of all mothers return to work before their youngest child's second birthday. By inspecting the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) one can observe that three-quarters of those mothers working prior to birth were back at work within a year of birth. Table 1 Percentage Change in Average Hours Worked by Age 1970 vs. 1990 (%) 25-34 35-44 45-54 Married men -0.12 -0.43 -1.5 Married women 96 70 49 Married women with kids<6 134 117 53 Married women with kids 6-17 55 61 58 Married women with no kids 36 40 37 Single Women 3 9 -0.1 Source: 1970 & 1990 Census Source: Olivetti,2000 These facts indicate that women are spending less time out of the labor force for child bearing and rearing. The consequences of this are twofold. On one hand, more rapid reemployment of new mothers will allow women to accumulate more actual labor market experience than their predecessors. A standard analysis would allow us to conclude that this would in general lead to higher wages, thus reducing both, the family and gender earnings gap. On the other hand, women's earlier return to work might have an impact on the development of their children. Medical and psychological literature has documented the fact that maternal vocabulary and maternal cognitive stimulation are strong predictors of children's cognitive development1.

In this paper, I focus on the labor supply decisions of women immediately following their first birth in order to understand what factors have contributed to the rapid growth in labor supply that has been observed among mothers of very young children. Additionally I explore the effects of new mother's decisions on the well being of their children. There is extensive literature on the impact of mothers' employment on children. Several sciences including economics, psychology, sociology and demography have shown evidence of a positive relationship between human capital investment by parents in children and the outcomes of these children. In other words, that such investments may lead to persistence of wealth (or lack of it) among generations of the same family. However, results are still far from conclusive despite the importance of such conclusions for public policy actions.

The key issue that I deal with in the paper is that women are heterogeneous in both the constraints they face and their tastes. At the same time, children are heterogeneous in their cognitive endowments. As we would expect, mothers’ decisions with regard to working when children are young, and/or placing children in childcare are influenced by these heterogeneous characteristics of both mothers and children. This sample selection issue makes evaluation of the effects of women’s decisions on child outcomes extremely difficult.

In order to deal with the selection bias problem I develop a model of the work and child care decisions of mothers in the first five years after the birth of a child. The model enables me to predict the typical characteristics of children whose mothers work and/or who are placed in childcare. The model generates predictions of whether these children differ systematically in terms of their cognitive endowments. I then estimate equations for child outcomes as a function of inputs (including the childcare and maternal work decisions, as well as observable characteristics such as education). In the spirit of Heckman’s (1979)2 approach, the first stage model can be used to predict unmeasured characteristics of the children (i.e. endowments), and these predicted characteristics can be used as additional controls when estimating the outcome equations. I extend with respect to the typical application of the Heckman approach by modeling the mothers as making sequential decisions about work and childcare in each 3-month period following birth until the child reaches school age, as opposed to just modeling a one-time decision. Thus, the model accommodates “dynamic selection” in which the typical characteristics of children whose mothers work or who are placed in child care may change as the child ages and the effects of mothers’ decisions on child outcomes may vary with the age of the child.

This estimation provides much more reliable estimates of the impact of mothers’ work and child care decisions on child outcomes, which allow me to conduct an evaluation of policies such as parental leave, childcare and those related to state benefits and incentives for women to take up paid work.

1 National Institute of Health. ''Results of NICHD Study of Early Child Care'', Reported at Society for Research in Child Development Meetings. 2 Heckman, J. (1979) “Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error”, Econometrica, 47,153-161.