Contracts Outline – Spring 2003

Avoidance Public Policy – Some terms or contracts may not be enforced because they are contrary to public policy. This is a distinct doctrine and not the same as unconscionability. Where does the court look to decide if something violates public policy? o Constitution, the legislature, and the judiciary (common law of public policy) and also local ordinance, rule of professional responsibility, administrative regulation – these are all comparable kinds of sources for what public policy is. o In the absence of such a declaration, we look to whether the agreement has a tendency to injure the public or is against the public good. o See R2d 178 and 179 [and Notes pg. 4]

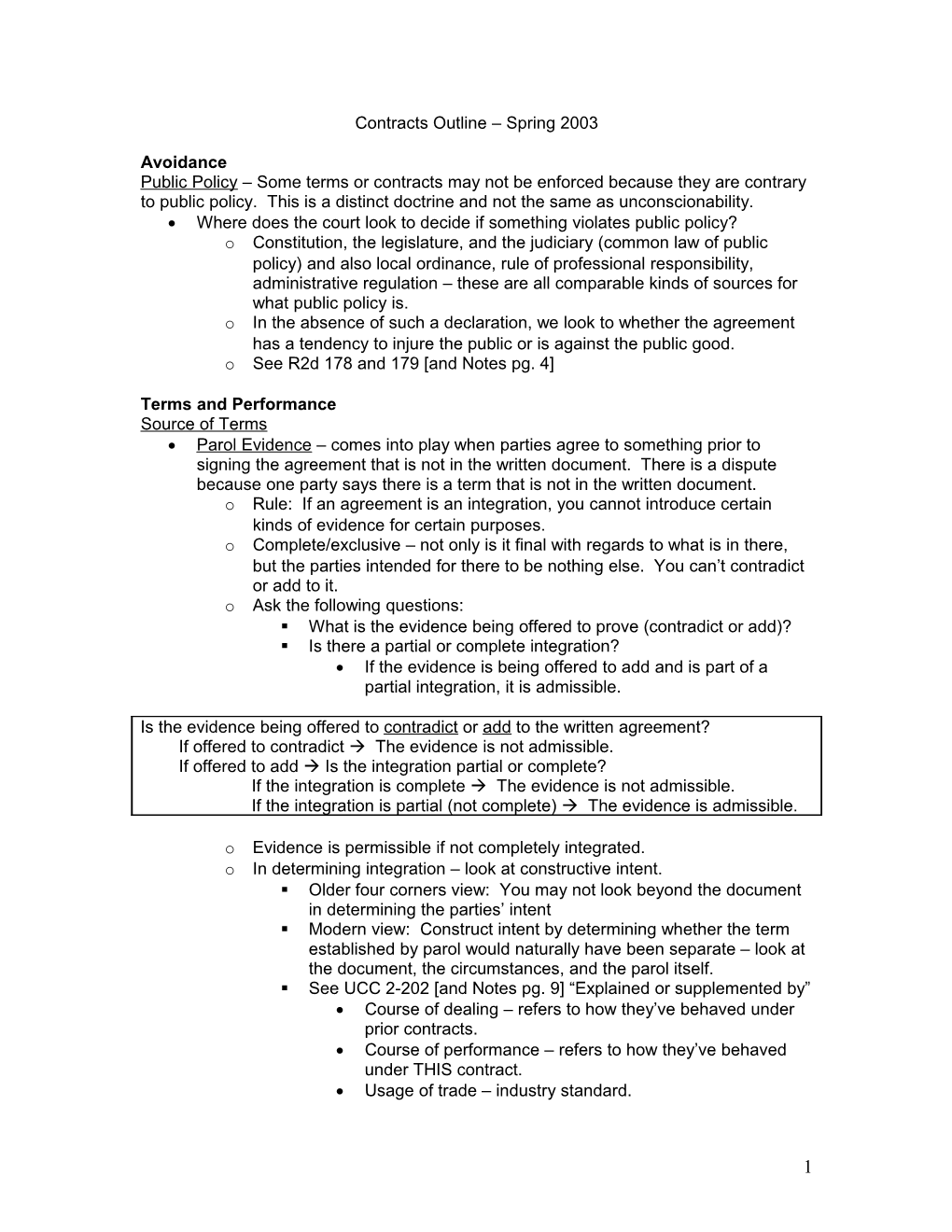

Terms and Performance Source of Terms Parol Evidence – comes into play when parties agree to something prior to signing the agreement that is not in the written document. There is a dispute because one party says there is a term that is not in the written document. o Rule: If an agreement is an integration, you cannot introduce certain kinds of evidence for certain purposes. o Complete/exclusive – not only is it final with regards to what is in there, but the parties intended for there to be nothing else. You can’t contradict or add to it. o Ask the following questions: . What is the evidence being offered to prove (contradict or add)? . Is there a partial or complete integration? If the evidence is being offered to add and is part of a partial integration, it is admissible.

Is the evidence being offered to contradict or add to the written agreement? If offered to contradict The evidence is not admissible. If offered to add Is the integration partial or complete? If the integration is complete The evidence is not admissible. If the integration is partial (not complete) The evidence is admissible.

o Evidence is permissible if not completely integrated. o In determining integration – look at constructive intent. . Older four corners view: You may not look beyond the document in determining the parties’ intent . Modern view: Construct intent by determining whether the term established by parol would naturally have been separate – look at the document, the circumstances, and the parol itself. . See UCC 2-202 [and Notes pg. 9] “Explained or supplemented by” Course of dealing – refers to how they’ve behaved under prior contracts. Course of performance – refers to how they’ve behaved under THIS contract. Usage of trade – industry standard.

1 Implied-in-fact Terms o Every contract has an implied contract of good faith and fair dealing – this is an immutable default term. o Pugh v. See’s Candies case

Terms Supplied by Default Rules o Implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose – see UCC 3-315 [and Notes pg. 10] . A “particular purpose” differs from the ordinary purpose for which goods are used in that it envisages a specific use by the buyer which is peculiar to the nature of his business whereas the ordinary purposes for which goods are used are those envisaged in the concept of merchantability and go to uses which are customarily made of the goods in question. This is like the case of the guy who bought the SUV for his wilderness business – the seller had no way of knowing it wasn’t for regular use because the guy didn’t tell him. Another example is shoes – a seller might know a particular pair was chosen to be used for climbing mountains. o Implied warranty of merchantability – see UCC 2-314 [and Notes pg. 10] . This warranty only comes from a merchant seller. . (c) is key: “must be fit for the ordinary purposes for which such goods are used.” o Express warranty – see UCC 2-313 [and Notes pg. 11] . There is no requirement that in order to find an express warranty it has to be written. Example: When the guy at the computer store told the buyer “any of these will do,” he created an express warranty. . “Puffing” v. warranty – the more specific, the more likely it is to be an express warranty. Standards and verifiable make it more of an express warranty. (Puffing would be “It’s a wonderful car” and warranty would be “it has four cylinders.) o “As Is” Clauses – see UCC 2-316 [and Notes pg. 12] . According to Bailey v. Tucker Equipment Sales, “as is” clauses must stand out in any warranty or writing. A person has to have noticed and understood that the disclaimer was meant to take away their rights to implied warranty of merchantability. So even if the words were conspicuous, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the consumer would understand what it means. . According to 2-316 – If an oral express warranty seems to be canceled out by a written as is clause, one of these is inoperative. If the negation statement is written, you have to look at parol evidence rule to see if the oral statement could even be introduced. [See Notes pg. 13]

Interpretation of Terms General Principles – Interpretation issues are discussed in the Athlete Endorsement problem. [Notes pg. 16]

2 o Prytania Park Hotel v. General Star Indemnity – crucial language in this case was “permanently installed fixtures” v. “furniture and fixtures.” The court said since “fixtures” was used in both phrases, but “furniture” was not, furniture was specifically NOT to be included in the one it was not mentioned in. o Rules of interpretation used in Frigalament v. BNS International Sales (the chicken case): . Actual language of the contract – did the contract define chicken? . Circumstances at the time the contract was being negotiated – in this case it was market price of better chickens. . Use the entire contract to see if one part of it, one phrase elsewhere that gives rise that you are interpreting that meaning. . Trade usage – the court says you can use this to interpret if the person new to the trade knows the trade usage or if the usage is so powerful that they should have known the trade usage. . Conduct after execution of the contract to show what they actually meant. . Look at the negotiations to understand what a party might have meant by something. Extrinsic Evidence – everything not included in the written agreement. This includes both parol evidence and course of dealing, etc. o Extrinsic evidence to aid interpretation – negotiations, parol evidence, usage, course of dealing, course of performance.

Nature and Effect of Terms Promises and Conditions o Promise – A promise is a commitment to do or refrain from doing something. The promise in the contract may be unconditional or conditional. An unconditional promise is absolute; a conditional promise may become absolute by the occurrence of the condition. If the promise is unconditional, the failure to perform according to its terms is a breach of contract. o Condition – A condition is an event, other than the passage of time, the occurrence or non-occurrence of which will create, limit, or extinguish the other contracting party’s absolute duty to perform. A condition is a “promise modifier.” There can be no breach of promise until the promisor is under an immediate duty to perform. He may insert conditions on his promise to prevent that duty of immediate performance from arising until the conditions are met. The failure of a contractual provision that is only a condition is not a breach of contract, but it discharges the liability of the promisor whose obligations on the conditional promise never mature. . Condition precedent – a condition precedent is one that must occur before an absolute duty of immediate performance arises in the other party. o Promise v. condition – . Breach of promise gives rise to a cause of action for breach. . Failure of a condition means that someone’s performance is conditioned on an event the other party’s promise is eliminated.

3 Constructive conditions of impossibility, impracticability, and frustration – you have to look at the party seeking discharge and if their performance is impracticable or frustrated o Impracticability – the party seeking discharge claims its performance is impracticable o Frustration – the party seeking the discharge claims that the promised return is nearly useless o Example: Refrigerator Problem . UCC 2-615 is a general rule that excuses the seller from performing under various circumstances. . Also see UCC 2-503, 2-509, 2-709 [and Notes pg. 27]

Breach Discharging Remaining Duties of the Injured Party If you have 2 parties and one there’s a bilateral contract in which both parties have made one or more promises: o One party’s promise is due prior to the other party’s promise. For example, B promised to pain and A promised to pay after B paints. o If the one promise must be performed before the other, that promise is a constructive condition to performance of a promise. This means that if B doesn’t paint, then A doesn’t have to pay. A can also get damages for B’s breach. o B’s breach may be very insignificant (like forgetting one inch of a door), but they have still breached. It would be silly to say that A is discharged from his promise to pay in a case like this. To deal with situations like this, the common law rule is that the person still has to perform their promise unless the breach was material. When is a breach material? See R2d 241 for factors for determining material breach [and Notes 30]. If a breach is not material, it is the same as saying there was substantial performance – this language is usually used for construction contracts. o (a) Extent of deprivation of benefit to injured party: greater = material, lesser = not material. o (b) Adequacy of compensation to injured party: greater = not material, lesser = material. o (c) Extent of forfeiture by breacher: greater = not material, lesser = material. o (d) Likelihood of cure by breacher: greater = not material, lesser = material. o (e) Breacher comply with standards of good faith and fair dealing: yes = not material, no = material. If goods fail to conform to the contract, what can the buyer do? o See UCC 2-601 for the buyer’s rights [and Notes 33]. Buyer can reject the whole, accept the whole, or accept any commercial unit or units and reject the rest. Under 2-601, buyer can reject if the goods fail “in ANY respect” to conform to the contract – this is known as the Perfect Tender Rule. o If you have accepted goods, you may not reject them. SO, what is an acceptance? See UCC 2-606 [and Notes 33].

4 o If you accept the goods, you have to pay the contract price but you can get damages. o If buyer rightfully rejects the goods, they can cancel which means buyer doesn’t pay and there is a remedy against the seller for breach.

Restitution for the Breaching Party Factors to look at: o Has performance by the breaching party conferred a benefit? o Will court consider the culpability of the breaching party? o How do you measure the value of the benefit? Generally, this is the lesser of: . Increase in wealth, or . Cost if obtained elsewhere. o Subtract damages owed to the aggrieved party. See R2d 237 and R2d 240 [and Notes pg. 37] How to know whose performance is due first: See R2d 234 [and Notes pg. 37] Restitution is an overall theory of liability o Quantum meruit – value of services rendered (pleaded by the common court) How is restitution measured? See R2d 371 [and Notes pg. 39] Generally speaking, (b) from 371 is lower than (a). And because the person seeking restitution is the one who breached, they should get the lower amount. (But Neustadter disagrees with this because he doesn’t think culpability should be involved at all.) o Specifically for the breaching party, see R2d 374 [and Notes pg. 40]

Anticipatory Repudiation and Adequate Assurance of Performance Anticipatory Repudiation – when there has been a repudiation of the contract by one party before the time for his performance has arrived, the other party may treat the entire contract as breached and commence suit without delay. Resort to this doctrine is at the election of the non-breaching party. However, there must be a definite and final communication of the intention to forego performance before the anticipated breach may be the subject of legal action. Mere expression of difficulty in tendering the required performance, for example, is not tantamount to a renunciation of the contract. o Hochster v. De La Tour – at the time this case was decided, it was unclear if you could sue for damages in advance of the time the performance was due. The holding was that after the renunciation of the agreement by one party, the other party should be at liberty to consider himself absolved from any future performance of it, retaining his right to sue for any damage he has suffered from the breach of it. o See R2d 250 for when a statement or act is a repudiation [and Notes pg. 41] Adequate Assurance of Performance – See UCC 2-609 [and Notes pg. 44] o Reasonable grounds to insecurity prior to own breach o Reasonable written demand for assurance o Nature and timing of response o Treat absence of timely, sufficient response as repudiation

5 Remedies For buyer’s remedies in general, see UCC 2-711 [and Notes pg. 46] For seller’s remedies in general, see UCC 2-703 [and Notes pg. 47]

Remedy of Specific Performance or Injunction o Specific performance – this is often in land buying cases because land is considered unique and damages are not specific to the buyer. If goods are considered unique, UCC says the buyer may have specific performance. . This remedy is rarely evoked for breach of contract. . Usually just for aggrieved purchaser of real property or unique goods. o Injunction (in lieu of specific performance) – per the Smith v. Burnett case, in order to get an injunction to keep someone from working somewhere else, you must prove that the person’s skill or talent is unique.

Remedy of Compensatory Damages o Expectation Measure – see Porsche problems on Notes pg. 47. . Incidental damages – For the buyer (if the seller breaches): Incidental damages resulting from the seller's breach include expenses reasonably incurred in inspection, receipt, transportation and care and custody of goods rightfully rejected, any commercially reasonable charges, expenses or commissions in connection with effecting cover and any other reasonable expense incident to the delay or other breach. (UCC 2-715(1)) For the seller (if the buyer breaches): Incidental damages to an aggrieved seller include any commercially reasonable charges, expenses or commissions incurred in stopping delivery, in the transportation, care and custody of goods after the buyer's breach, in connection with return or resale of the goods or otherwise resulting from the breach.

. Consequential damages – For the buyer (if the seller breaches): Consequential damages resulting from the seller's breach include (a) any loss resulting from general or particular requirements and needs of which the seller at the time of contracting had reason to know and which could not reasonably be prevented by cover or otherwise; and (b) injury to person or property proximately resulting from any breach of warranty. (UCC 2-715(2))

o Limitations on Recovery of Damages: Foreseeability, Avoidable Consequences, Reasonable Certainty . Damages must be reasonably foreseeable

6 Hadley v. Baxendale – case of the mill with the broken shaft. The court said they couldn’t recover for lost profits because the damages were not naturally-arising. The courier service had no way of knowing that the mill didn’t have an extra shaft and would stop operations if the fixed shaft didn’t get to them in time. . Attempt to avoid damages or make an affirmative effort to reduce the damages Rockingham County v. Luten Bridge Co. – the county breached and told Luten, but he kept working on the bridge anyway. Courts says you can’t just keep working and racking up damages if you had notice of the breach by the other party. You have a duty to mitigate damages. Parker v. Twentieth Century Fox – regarding taking alternate employment as a way to mitigate damages. Court said she didn’t have to take the alternate employment because it wasn’t comparable [see Notes 53] . Damages must be provable with reasonable certainty o Alternative Measures: Reliance or Restitution – used when the expectation measure is inadequate or can’t readily be used. . Reliance – a reliance measure puts you back in the position you would have been in if the contract had never been made in the first place. [See Notes pg. 55] . Restitution – the breaching party disgorges unjust enrichment. The most common instance of this is the Algernon Blair case.

Agreements about Remedies Liquidated Damages – see R2d 356 [and Notes pg. 57] o Not enforceable if a penalty Alternative remedies (repair/replacement), subject to consumer protection (lemon) laws Exclusion or limitation of consequential damages – see UCC 2-719 [and Notes pg. 57] o Key question is whether the limitation was expressly agreed to be exclusive. If it was, it will usually explicitly say “exclusive.” If not, you can argue otherwise.

7