Case Study 1.15 The Black Rubric

The Black Rubric

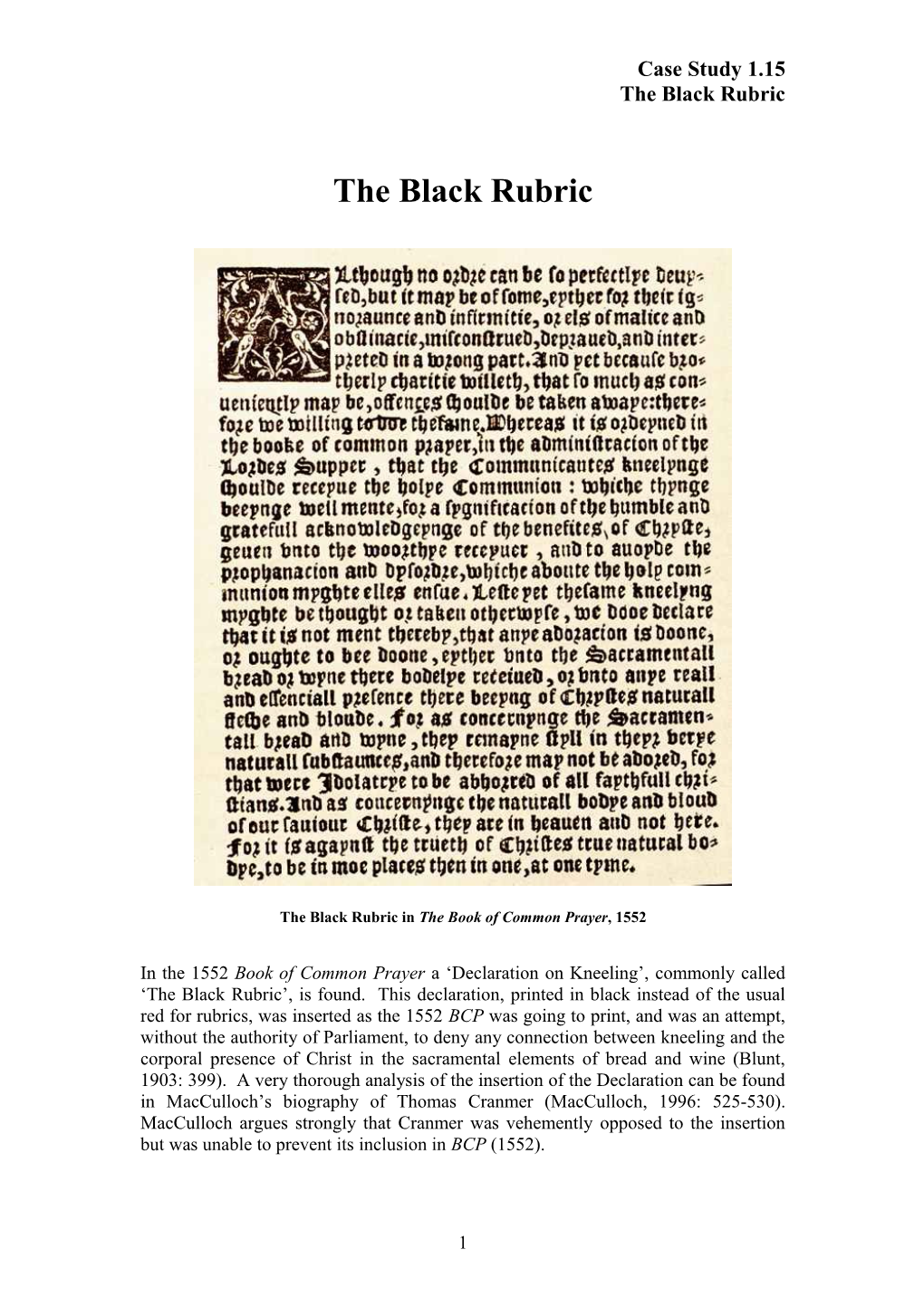

The Black Rubric in The Book of Common Prayer, 1552

In the 1552 Book of Common Prayer a ‘Declaration on Kneeling’, commonly called ‘The Black Rubric’, is found. This declaration, printed in black instead of the usual red for rubrics, was inserted as the 1552 BCP was going to print, and was an attempt, without the authority of Parliament, to deny any connection between kneeling and the corporal presence of Christ in the sacramental elements of bread and wine (Blunt, 1903: 399). A very thorough analysis of the insertion of the Declaration can be found in MacCulloch’s biography of Thomas Cranmer (MacCulloch, 1996: 525-530). MacCulloch argues strongly that Cranmer was vehemently opposed to the insertion but was unable to prevent its inclusion in BCP (1552).

1 Case Study 1.15 The Black Rubric

The 1552 Declaration read, in part, in relation to kneeling at the time of receiving the bread and wine:

“ … Lest yet the same kneeling might be thought or taken otherwise, we do declare that it is not meant thereby, that any adoration is done, or ought to be done, either unto the sacramental bread and wine thereby bodily received, or to any real and essential presence, there being of Christ’s natural flesh and blood.” (1552 BCP, edn. Ketley, 1844: 283).

‘Essential’ is equivalent, in the scholastic language being excluded by the Declaration, to ‘substantial’ (Tomlinson, 1897: 264). The Greek word ousia (meaning substance) is translated into Latin by the word substantia, meaning substance or essence (Stead, 1983: 554 and Lewis and Short, 1980: 1782). The Latin word essentia (meaning essence or being of a thing) also stood for the Greek work ousia (Stead, 1983: 186 and Lewis and Short, 1980: 660). The phrase ‘real and essential’ therefore carries the same meaning as ‘real and substantial’.

The Declaration on Kneeling was significantly altered in BCP (1662). This was done, it seems, to avoid any confusion between the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist on the one hand and the doctrine of transubstantiation on the other (Proctor and Frere, 1929: 394). Transubstantiation is specifically rejected by the Thirty Nine Articles (Article XXVIII), however, there is no specific rejection of what is known as the ‘real presence’ of Christ in the Eucharist. The doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, as usually expressed by Anglican theologians, does not involve any change in the substance of the bread and wine. In BCP (1662) the Declaration therefore became in part:

“ ….. yet, lest the same kneeling should by any persons either out of ignorance and infirmity, or out of malice and obstinacy, be misconstrued and depraved: It is hereby declared, that thereby no Adoration is intended, or ought to be done, either unto the Sacramental Bread and Wine there bodily received, or unto any Corporal Presence of Christ’s natural Flesh and Blood.” (BCP, 1662: Declaration of Kneeling).

Significantly the words ‘real and essential presence’ in BCP (1552) were changed to ‘corporal presence’ in BCP (1662). Some argue that the change is merely verbal, and not theological, since the words ‘real and essential’ were no longer properly understood and could be misconstrued to mean the denial of any true form or presence (Tomlinson, 1897: 264). Others however, argue more forcefully for the change in wording as indicating an affirmation of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist (Wheatly, 1864: 323-324; Pullan, 1900: 316; Blunt, 1903: 399; Daniel, 1913: 394- 396, Neil and Willoughby, 1913: 273-275).

The achievement of the framers of BCP (1662) in changing the wording from ‘real and essential presence’ to ‘corporal presence’ was that they maintained the protest against transubstantiation, whilst at the same time removing any risk of the Declaration on Kneeling being misconstrued as a denial of the real presence (Blunt, 1903: 399). Any continued use of ‘real and essential’ would have been misconstrued into a denial of the true and spiritual real presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

2 Case Study 1.15 The Black Rubric

‘Corporal’ makes its clear that material body is meant and that this is distinguished from a real and spiritual presence (Harford et al., 1912: 106).

If ‘real and essential’ is maintained in the Black Rubric then moderate realism is excluded as a way of describing the presence of Christ in the Eucharist. By replacing ‘real and essential’ with ‘corporal’, immoderate realism is excluded as a way of describing the presence of Christ in the Eucharist and moderate realism is not excluded. The fact that this change was made means that a realist conception was accepted in the amendments to the Declaration in the BCP of 1662 and that the moderate form of realism was preferred. The Declaration on Kneeling therefore, as it presently exists, suggests the possibility of a moderate realist of Christ in the Eucharist.

3