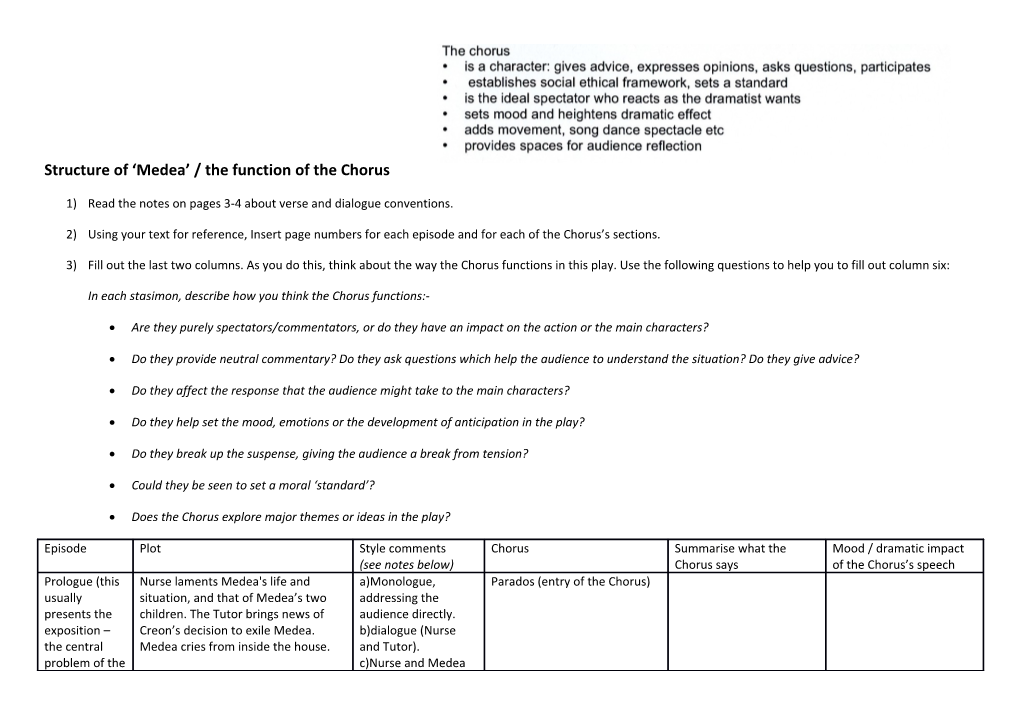

Structure of ‘Medea’ / the function of the Chorus

1) Read the notes on pages 3-4 about verse and dialogue conventions.

2) Using your text for reference, Insert page numbers for each episode and for each of the Chorus’s sections.

3) Fill out the last two columns. As you do this, think about the way the Chorus functions in this play. Use the following questions to help you to fill out column six:

In each stasimon, describe how you think the Chorus functions:-

Are they purely spectators/commentators, or do they have an impact on the action or the main characters?

Do they provide neutral commentary? Do they ask questions which help the audience to understand the situation? Do they give advice?

Do they affect the response that the audience might take to the main characters?

Do they help set the mood, emotions or the development of anticipation in the play?

Do they break up the suspense, giving the audience a break from tension?

Could they be seen to set a moral ‘standard’?

Does the Chorus explore major themes or ideas in the play?

Episode Plot Style comments Chorus Summarise what the Mood / dramatic impact (see notes below) Chorus says of the Chorus’s speech Prologue (this Nurse laments Medea's life and a)Monologue, Parados (entry of the Chorus) usually situation, and that of Medea’s two addressing the presents the children. The Tutor brings news of audience directly. exposition – Creon’s decision to exile Medea. b)dialogue (Nurse the central Medea cries from inside the house. and Tutor). problem of the c)Nurse and Medea play) (from inside the house) Episode 1 Medea emerges. She explains the lot a)Medea and Chorus; Stasimon 1 of women in general. Creon b)dialogue Medea pronounces her exile, but allows her a and Creon day's grace. Medea plans her (stichomythia: line- revenge. for-line dialogue, often compressed); c)Medea and Chorus Episode 2 Jason visits Medea, who denounces a)agôn logôn (the Stasimon 2 him. He defends his actions. ‘contest of speeches’) between Jason and Medea b)Medea and Chorus Episode 3 Aegeus agrees to offer Medea asylum a)Medea and Creon Stasimon 3 in Athens if she helps him to solve his (stichomythia) childless situation. After he leaves, b) Medea and Chorus she announces her full revenge. Episode 4 Jason visits Medea again. This time a)Medea and Jason; Stasimon 4 she claims to have accepted her exile. children brought out Medea offers to send her sons gifts to Jason's new bride Glauce, and asks that her sons be allowed to remain in Corinth. Episode 5 The Tutor delivers the two boys to a)Medea and Tutor Stasimon 5 Medea, who has second thoughts dialogue about killing them. b)Medea monologue Episode 6 A Messenger brings news of the Messenger-rhesis Stasimon 6 deaths of Glauce and Creon. Medea then enters the house to kill her sons. Exodos Jason arrives to avenge his new wife’s a)Jason and Chorus Exodos of Chorus death, and discovers that his sons are (stichomythia) dead too. Medea refuses to allow b)Medea and Jason him to have the children’s bodies, and dialogue (includes escapes in a chariot that belongs to stichomythia) her grandfather, the sun god Helius. c)Jason

Notes on original verse forms in Greek tragedy

Every aspect of a Greek tragedy was formalised according to conventions.

1) Plot

In terms of plot, the audience is usually prepared for the plot by way of the exposition. Then the conflict is introduced, and complicated by the rising action of the play to the point of climax (the crisis or turning point – the point at which the potential for that particular action, born of the conflict, is realised). What remains is falling action, during which the action simplifies or unravels. The play ends in resolution, revealing the meaning of all that has preceded it.

2) Structure

The basic structure is one of acts and act-dividing songs. A new act normally starts with the entry of a new character after a song.

Writing within a conventional structure is a discipline that can create a tightly-structured, compressed plot.

There are a range of structural terms that are used to describe classical Greek tragedies:

Prologue: the part of the play preceding the entry of the chorus, usually two scenes (sometimes three, rarely one). The first of these scenes may be a prologue-monologue. The monologue-speaker may be a god, a minor character, or a major character. Such a speaker normally addresses the audience more or less directly, and full dramatic illusion does not take hold until the conclusion of the speech. The prologue is usually expository, introducing the central problem of the play. Parodos: entry of the chorus, either singing a song or chanting some verses. Episode(s): the scenes that present the action of the drama, positioned between two stasimons. Stasimon (or odes): passages spoken by the Chorus and alternating with the episodes. An ode is a type of lyric poem that uses dignified, exalted language. The Chorus sand and danced the tragic odes, accompanied by musical instruments. The stasimons tend to get shorter as the play proceeds. Exodos: the scene(s) following the final stasimon. In many plays of Euripides there is a divine epiphany in the exodos. Frequently the crane was employed for the god's appearance through the air: hence theos apo mêchanês, deus ex machina, "god from the crane"), but the god could also appear on the roof of the scene-building (via a ladder or trap-door). The exodus would conclude with the Chorus’s final lines as they exit.

3) Verse conventions

Plays alternated between song and speech

Chorus and actors

The language was in verse, with a range of metres for different types of speeches (eg. iambic trimeters – 12 syllables arranged in iambic feet). It’s hard for a translator to reflect these precisely.

4) Dialogue conventions

There were also a range of different types of dialogue. A long speech was called ‘rhesis’; some of these include elements of rhetoric and debate. The conventions of dialogue, particularly the use of stichomythia and the longer rhetorical speeches, reflect the focus on reasoned argument of the time. The Ancient Greeks conducted their civic affairs in open, formal debate and used oratory as the basis for public decision-making. In law courts, it was the practice to have speeches of equal length delivered by opposing sides, and accusations met by rebuttals. Citizens accepted these patterns of debate as a way of resolving differences. Importantly for ‘Medea’, moderation in all aspects of living was an ideal: the Greeks sought balance and order in all things. A common theme in Greek drama was man’s struggle between the rational and irrational.

In ‘Medea’ there are various speeches and dialogues that follow expected conventions, including:

the ‘messenger-rhesis’, where a messenger brings news from offstage. This often happens about 2/3 of the way through the play. Typically, the messenger conveys the essential news and relieves the tension in a short dialogue and then is asked to give the whole story, which he does in a rhesis extending up to 80 or even 100 lines. stichomythia (where the dialogue in a debate or argument is exchanged line-for-line by the 2 main actors.

the ‘agôn logôn’: the "contest of speeches". The two debaters may be performing in front of a third actor who serves more or less as "judge" (the Chorus has this function in ‘Medea’). In many cases the rheseis of the debate are followed by argumentative short dialogue or stichomythia which sharpens the opposition and shows that nothing positive has been accomplished.

(Notes taken from various sources including http://ucbclassics.dreamhosters.com/djm/classes/Structure.html )

.