WT/TPR/S/219 Trade Policy Review Page 74

V. AID FOR TRADE

(1) OVERVIEW

1. The Aid-for-Trade Initiative was launched at the WTO Hong Kong Ministerial Conference where Ministers agreed that aid for trade should aim to help developing countries, particularly LDCs, to build the supply-side capacity and trade-related infrastructure that they need to assist them to implement and benefit from WTO agreements and more broadly to expand their trade.1 Zambia has been at the forefront of aid-for-trade discussions and represented the LDCs in the Aid-for-Trade Task Force created pursuant to the Hong Kong Ministerial Declaration.2 For the LDCs, the priorities that aid for trade should address include strengthening their supply-side capacity, which is often closely linked with improvements in their infrastructure. The first global aid-for-trade review was held in November 2007.

2. In 2008, the focus was to shift emphasis to monitoring implementation as well as to launch a work programme to develop performance indicators and to strengthen self evaluations. A questionnaire aimed at assisting developing countries to identify their needs has been developed and circulated to beneficiary countries, including Zambia. In its responses, Zambia has identified its three key priority areas of intervention to improve its capacity to benefit from trade expansion and integration into the world economy. These are: network infrastructure (power, water, telecommunication); cross-border infrastructure; and export diversification. Other areas include: trade policy analysis, negotiation and implementation; trade facilitation; adjustment costs; competitiveness and regional integration. The responses to the questionnaires will feed into the next global aid-for-trade review scheduled for July 2009.

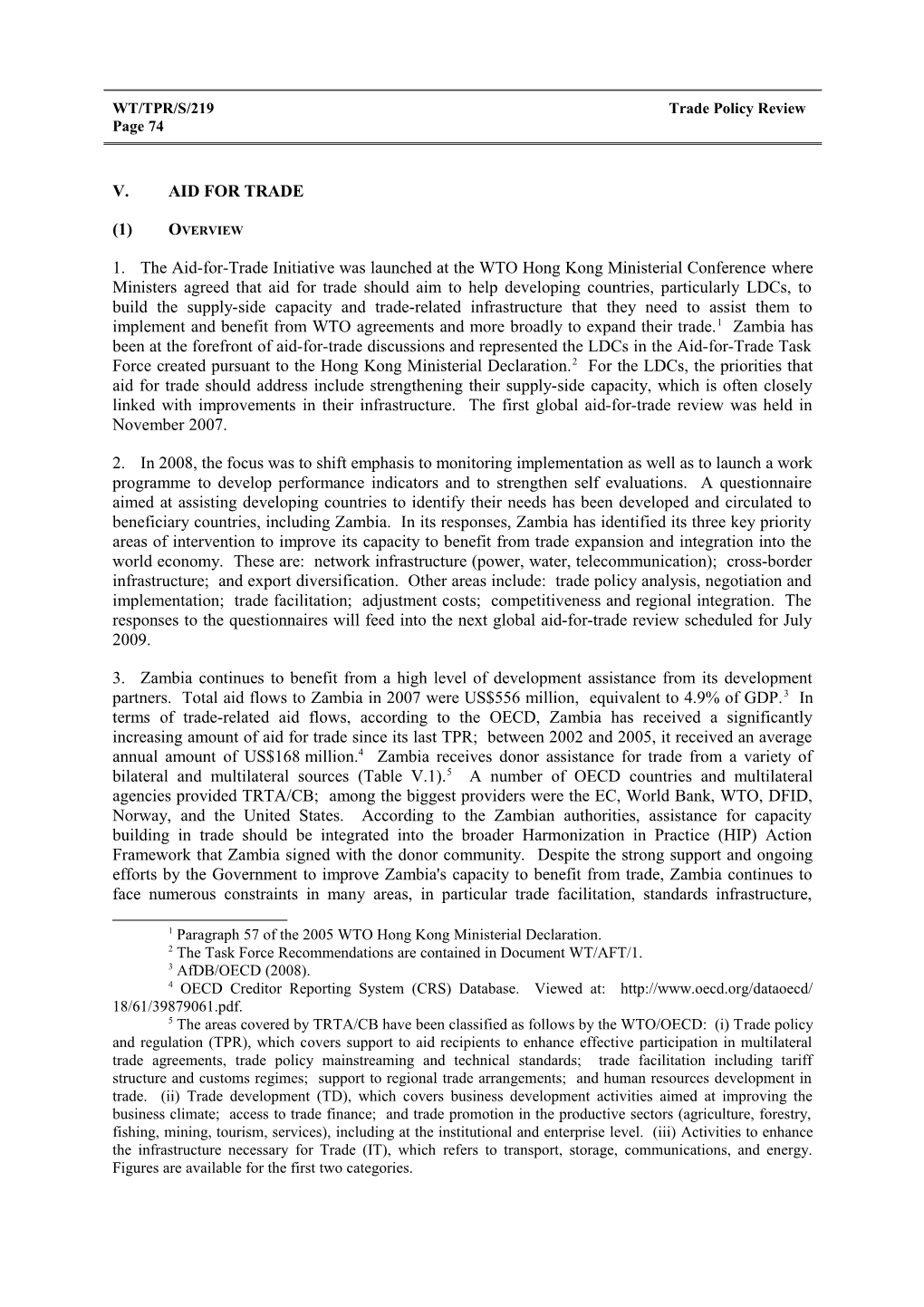

3. Zambia continues to benefit from a high level of development assistance from its development partners. Total aid flows to Zambia in 2007 were US$556 million, equivalent to 4.9% of GDP.3 In terms of trade-related aid flows, according to the OECD, Zambia has received a significantly increasing amount of aid for trade since its last TPR; between 2002 and 2005, it received an average annual amount of US$168 million.4 Zambia receives donor assistance for trade from a variety of bilateral and multilateral sources (Table V.1).5 A number of OECD countries and multilateral agencies provided TRTA/CB; among the biggest providers were the EC, World Bank, WTO, DFID, Norway, and the United States. According to the Zambian authorities, assistance for capacity building in trade should be integrated into the broader Harmonization in Practice (HIP) Action Framework that Zambia signed with the donor community. Despite the strong support and ongoing efforts by the Government to improve Zambia's capacity to benefit from trade, Zambia continues to face numerous constraints in many areas, in particular trade facilitation, standards infrastructure,

1 Paragraph 57 of the 2005 WTO Hong Kong Ministerial Declaration. 2 The Task Force Recommendations are contained in Document WT/AFT/1. 3 AfDB/OECD (2008). 4 OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS) Database. Viewed at: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/ 18/61/39879061.pdf. 5 The areas covered by TRTA/CB have been classified as follows by the WTO/OECD: (i) Trade policy and regulation (TPR), which covers support to aid recipients to enhance effective participation in multilateral trade agreements, trade policy mainstreaming and technical standards; trade facilitation including tariff structure and customs regimes; support to regional trade arrangements; and human resources development in trade. (ii) Trade development (TD), which covers business development activities aimed at improving the business climate; access to trade finance; and trade promotion in the productive sectors (agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining, tourism, services), including at the institutional and enterprise level. (iii) Activities to enhance the infrastructure necessary for Trade (IT), which refers to transport, storage, communications, and energy. Figures are available for the first two categories.

WT/TPR/S/219 Trade Policy Review Page 75 enforcement of intellectual property rights, notifications, trade remedies, training of officials, and private-sector development.

Table V.1 Trade capacity building in Zambia, 2002-07 Trade Policy and Regulations (TPR) Trade Development (TD) 2002 Activities 40 34 US$'000 827 5,047 2003 Activities 45 23 US$'000 612 5,866 2004 Activities 46 22 US$'000 1,599 5,967 2005 Activities 57 31 US$'000 925 24,038 2006 Activities 46 44 US$'000 9,536 7,718 2007a Activities 22 2 US$'000 168 1,077 a Partial data. Note: Amounts include only grants and concessional loans. Non-concessional loans (i.e. market-rate loans – mainly those from EBRD and IBRD) and self-financed activities (i.e. activities financed by a developing country for itself and implemented by a multilateral TA agency) are excluded, because they are not considered as aid. Number of activities: some donors split individual activities (workshop/project, etc.) to provide detailed data on aid allocated to each of the sub-categories of TRTA/CB. Others classify the whole activity under the most relevant sub-category. Some donors make a further breakdown of regional activities by splitting amounts between different beneficiary countries. Others simply report such activities as "regional" or "global" projects and programmes. See explanatory note on the website. Source: DDA Trade Capacity Building Database for Zambia. Viewed at: http://tcbdb.wto.org/ben_country.aspx? entityID=112#.

(2) INTEGRATED FRAMEWORK (IF)

4. The Aid-for-Trade Task Force recognized the Integrated Framework as an effective mechanism for identifying LDC trade needs and priorities and for donors to meet those needs. In 2005, a Task Force on the Integrated Framework was established to provide recommendations for an Enhanced Integrated Framework. Zambia was an active member of the IF Task Force, which recommended three areas that would constitute the Enhanced IF.6 Zambia is a beneficiary of the Integrated Framework.7 Approved by the Cabinet in 2006, the (2005) Diagnostic Trade Integration Study

6 The three areas are: (i) provision of increased, predictable, and additional funding on a multi-year basis; (ii) strengthening of the IF in-country, including through mainstreaming trade into national development plans and poverty reduction strategies; more effective follow-up to diagnostic trade integration studies (DTIS), and implementation of action matrices; and achieving greater and more effective coordination amongst donors and IF stakeholders, including beneficiaries; and (iii) improvement in the IF decision-making and management structure to ensure an effective and timely delivery of the increased financial resources and programmes. 7 The IF process consists of several phases: (1) preparation of a Diagnostic Trade Integration Study (DTIS) to identify constraints to traders, sectors of greatest export potential, and an action matrix for better

Zambia WT/TPR/S/219 Page 76

(DTIS) reviewed Zambia's trade policies and performance, assessed its potential for export diversification, identified the main constraints to increasing exports, and developed an action matrix summarizing the policy reforms and technical assistance needed.

5. The Zambia DTIS concluded that, to support export diversification, the key priority areas in trade policy were to: (i) eliminate anti-export bias and make export incentives work for exporters; (ii) improve trade facilitation; and (iii) enhance the authorities' capacity to formulate, coordinate, and implement trade policy, and negotiate trade agreements. It also concluded that further liberalization of imports was a lesser priority, although duties on imported capital goods should be removed to stimulate private-sector investment. Moreover, it found that market access was not a constraint on export growth, as most of Zambia's exports face zero or low tariffs and qualify for preferential access to the major developed country and regional markets.8 The DTIS further identified the key requirements for the effective implementation of Zambia's export-oriented trade strategy. These include: high-level political commitment; mainstreaming of trade policy in Zambia's development and poverty reduction strategy; greater coordination within government; effective public-private partnership; enhanced trade capacity; and donor coordination.

6. Drawing in part on the DTIS, the authorities have incorporated a number of export promoting trade policy measures into the Fifth National Development Plan. Furthermore, the DTIS findings are incorporated into the Private Sector Development Programme, and IF implementation is being supported through a "Window II" project to build institutional capacity to manage the IF process in-country. Many of the areas identified in the action matrix of the DTIS are being addressed by Zambia's bilateral and multilateral development partners.

Joint Integrated Technical Assistance Programme (JITAP II)

7. Zambia has benefited from phase II of the Joint Integrated Technical Assistance Programme (JITAP), implemented jointly by ITC, UNCTAD and WTO, and financed by several donor countries. JITAP's objective is to assist African countries build endogenous capacities to integrate effectively and beneficially into the multilateral trading system (MTS).9

8. JITAP II, of which Zambia has been part since 2003, aims at building and/or strengthening, in partner countries, human, institutional and entrepreneurial capacities in five main areas: (a) trade negotiations, implementation of WTO agreements, and related-trade policy formulation through the Inter-Institutional Committees (IICs) that are official frameworks to organize national stakeholder discussion and decision making on the MTS; (b) MTS reference centres and national enquiry points (NEPs) for providing reliable technical information on the MTS, with attention to standards and quality requirements; (c) development of the national knowledge base on MTS through training of trainers and formation of trainer networks; (d) development of a goods, commodities, and services policy framework and sectoral strategies, including market knowledge of exporting and export-ready enterprises to develop production and exports; and (e) networking of the institutional and human capacities built in each country to encourage synergy and exchange of expertise and experiences, integration into the global trading system; (2) integration of the action matrix into the national development strategy; and (3) implementation of the action matrix in partnership with the development cooperation community. 8 World Bank (2005b). 9 The first phase of JITAP, which started with eight beneficiary countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Tunisia, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania), was completed in December 2002. Phase II was launched in February 2003 for a period of four years up to 2007. The 16 African countries benefiting from the programme are the 8 original countries plus Botswana, Cameroon, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Senegal, and Zambia.

WT/TPR/S/219 Trade Policy Review Page 77 including at the sub-regional level, to ensure sustainability of such capacities beyond the programme's life.

9. At the conclusion of JITAP II in 2007, the Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry (MCTI) as the focal point for the JITAP, indicated that the technical assistance programme had made a tangible, albeit modest, contribution to the country's economic and social development. It is difficult to accurately state the magnitude of the contribution, since Zambia, like other JITAP countries, has received a number of TRTAs with similar mandates. However, the MCTI has said the JITAP has been "very significant" in: nurturing an MTS knowledge/resource pool, building a multi-stakeholder consultative mechanism, and influencing the formulation of trade programmes among stakeholders. It is credited with increasing the country's knowledge-base on MTS issues and fostering the creation of a consultative mechanism. Zambia is using the JITAP to enhance its capacity to participate effectively in and benefit from the MTS. One such challenge is a lack of knowledge about the impact that MTS negotiations can have on the Zambian economy and all segments of Zambian society. There is need for systematic sensitization of private- and public-sector representatives. However, the inter-institutional committee (IIC) established under the JITAP is helping Zambia to stimulate national awareness of MTS issues and preparedness for negotiations.

(3) BILATERAL AID: MILLENNIUM CHALLENGE

10. The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) was established by the United States in 2004 "to provide greater resources for developing countries taking greater responsibility for their own development." Nine sub-Saharan nations, including Zambia, have participated in the MCC's Threshold Country Program, designed to assist countries on the "threshold" of MCC eligibility for larger assistance.

11. From July 2006, USAID worked closely with the Zambian Government for a two-year period to implement a US$24.3 million programme that targeted three important areas: (i) addressing administrative corruption by helping to simplify and streamline business processes at the Ministry of Lands, the Department of Immigration, and the Zambia Revenue Authority; (ii) improving the environment for doing business in Zambia, by helping the newly created Zambia Development Agency to simplify business registration, licensing, and inspection procedures, and to rationalize the economic regulatory framework, and by supporting provincial offices of the Patent and Companies Registration Office (PACRO) to facilitate greater business and investment creation outside of the capital; and (iii) facilitating trade by helping to increase the efficiency of procedures at the borders, through building capacity in modern customs techniques and integrating border control and management.

12. According to the USTR10, as a result of one of the programmes, the VAT registration process in Zambia has been reduced from 21 days to 3 days and the business registration process at the Patents and Companies Registration Office has been reduced from 10 days to 1, effectively reducing the number of days to start a business in Zambia from 35 to less than 10. With the support of the Millennium Challenge, the Zambian authorities note in the 5th NDP that a new programme is aimed at enhancing port efficiency through the establishment of a "Comprehensive Integrated Tariff System" (CITS) that will unify all border-related fees and procedures. The programme will start with two pilot border posts, Chirundu and Lusaka International Airport (LIA). The aim of the programme is to decrease and finally eliminate administrative and procedural barriers to trading.

10 Office of the United States Trade Representative (2008), p. 47.

Zambia WT/TPR/S/219 Page 78

(4) WTO TRADE-RELATED TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE

13. WTO trade-related technical assistance continues to be important in enhancing Zambia's integration into the MTS. In areas where the WTO does not have capacity, other partners (agencies and bilateral donors) provide the needed technical assistance. The areas requiring technical assistance, and technical assistance and capacity building programmes carried out include: general understanding of WTO agreements and Zambia's obligations emanating from the agreements, trade facilitation, notifications, TRIPs, standards and training of officials. These areas have also been identified in the IF Diagnostic Trade Integration Study (DTIS) for Zambia.

14. Zambia receives strong support from its development partners and many are active in the delivery of trade-related technical assistance at the national and regional levels. There are numerous technical assistance programmes of bilateral and multilateral agencies other than WTO and a comprehensive list is contained in the joint WTO/OECD Doha Development Agenda Database.11

(a) Trade facilitation

15. Due to Zambia's land-locked status, facilitating trade is a major challenge. Zambia's technical assistance needs in this area range from alleviating high transportation costs to improving customs administrations. Priority needs include: risk assessment methods; improvements in transparency; better use of IT; improving efficiency in customs administration through upgrading the customs infrastructure; reducing border clearance procedures; upgrading road and rail networks and reducing transport costs; integrating border agencies and developing a single processing and payment window; and training for officials.12

16. As part of the WTO trade facilitation negotiations, developing and least developed countries are encouraged to assess their trade facilitation needs and priorities. In this regard, in February 2007, Zambia was the first country to undertake a needs assessment.13 The needs assessment noted that Zambia was already consistent with 26 of the 71 proposals considered in the trade facilitation negotiations, partially consistent with 27, not consistent with 9 and that 9 were not yet applicable. The non-compliant areas include automated payment system; expedited shipments; single window submission; and pre-shipment inspection. In terms of participation in the negotiations on trade facilitation, Zambia has benefited from funding aimed at enabling capital-based officials to attend the negotiating meetings in Geneva.

17. A number of technical assistance activities are ongoing in Zambia in the area of trade facilitation, including regional initiatives under COMESA and SADC. Zambia has benefited from activities organized by the WTO, the World Customs Organisation, the World Bank, and UNCTAD. In addition to the national workshop on the needs assessment, Zambia participated in five regional workshops on trade facilitation between 2003 and 2007. Zambia also benefits from the USAID-funded trade facilitation and capacity building project managed by the Southern African Global Competitiveness Hub. The project provides support and technical assistance on a range of issues including customs modernization, transport facilitation, and trade capacity building.14

11 WTO online information. Viewed at: http://tcbdb.wto.org. 12 Chilala, Munyaradzi and Marawa (2006). 13 The assessment was conducted by WTO, World Bank and World Customs Organisation staff and funded by the WTO Doha Development Agenda Global Trust Fund (DDAGTF) and the World Bank. 14 Southern Africa Trade Hub online information. Viewed at: http://www.satradehub.org/index.php? id=2194.

WT/TPR/S/219 Trade Policy Review Page 79

18. In addition, DFID is funding a Regional Trade Facilitation Programme for Southern Africa, which includes streamlining transport, customs and border procedures, as well as developing a common regional transit system. A major pilot aid-for-trade programme is the North-South Corridor from the southern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo and northern Zambia to the port of Dar es Salaam in the north-east and the southern ports in South Africa. The European Union has an ongoing SADC programme, the Customs Modernisation and Trade Facilitation project, which supports harmonization of customs legislation and procedures, including transit flows, and assists in preparing for the SADC Customs Union in 2010.15

(b) TRIPS

19. Paragraph 2 of the TRIPS Council Decision of 29 November 200516, extends the transition period for LDCs to 1 July 2013, and invites LDC Members to provide the TRIPS Council, (preferably by 1 January 2008), with as much information as possible on their individual priority needs for technical and financial cooperation in order to assist them in taking steps necessary to implement the TRIPS Agreement.17 While Zambia is yet to present its needs assessment to the TRIPS Council, a preliminary discussion on Zambia's technical and financial needs took place between the WTO and Zambian officials in August 2007. A key concern for Zambia is the lack of a coordinated approach to intellectual property across different government agencies.18 In view of the need for an inclusive national IP policy and TRIPS implementation, the Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry established a new sub-group on TRIPS under the National Working Group on Trade.

20. In terms of notifying priority needs for technical and financial assistance, Zambia has requested further concrete involvement of the WTO Secretariat in the more detailed process of identifying such needs with respect to TRIPS implementation. The preliminary needs identified mainly relate to legislative compliance with the TRIPS Agreement. Zambia needs assistance in drafting national legislation and regulations where none exist, and in updating existing ones. For example, Zambia has no national legislation on geographical indications or on layout designs of integrated circuits. As is the case in many LDCs, enforcement of IP rights remains difficult to assess due to lack of information. Lack of information on infringement (copyrights, trade marks, patents, and industrial designs) as well as lack of necessary resources (financial and judicial) make it difficult for Zambia to enforce intellectual property rights, particularly at the border. In addition to legislative compliance, Zambia needs assistance in training officials as well as in sensitizing the public on intellectual property issues.

21. Since its last TPR, Zambia has benefited from a number of WTO technical assistance activities on TRIPS. It has also participated in a colloquium for developing country teachers of intellectual property organized annually by the WTO and WIPO since 2004. The objective of this initiative is to enhance the capacity in developing countries on IP matters and to develop an internal source of independent advice on policy issues. Zambia has participated in all regional workshops organized for English-speaking Africa since 2004. In August 2007, a national seminar on TRIPS and Public Health was held in Lusaka with the active participation of WIPO. The objective was to provide an improved understanding of the TRIPS Agreement as it relates to issues of public health, in particular with regard 15 Viewed at: http://www.delbwa.ec.europa.eu/en/eu_and_sadc/examples.htm. 16 WTO document IP/C/40. 17 The decision calls upon developed country Members to provide technical and financial cooperation in favour of LDC Members, in accordance with Article 67 of TRIPS, in order to effectively address the identified needs. 18 Whilst the Patents and Companies Registry Office (PACRO) is the most active agency in the area of IP, other government agencies are also involved such as the Ministry of Science, Technology and Vocational training and the Ministry of Health.

Zambia WT/TPR/S/219 Page 80 to its flexibilities including the implementation and application of the Paragraph 6 Decision on public health. Similarly, in November 2008, a national workshop on TRIPS was organized by the WTO, again with WIPO participation, to assist in the process of developing a national intellectual property policy for Zambia. The workshop focused on geographical indications, public health, plant variety protection, and enforcement of intellectual property rights, which are part of intensified discussions in Zambia.

(c) Standards

22. Like other LDCs, Zambia faces numerous challenges related to compliance with standards required by its trading partners, due to limited technical, human and financial resources. In addition, effective implementation of the WTO SPS and TBT agreements remain a challenge. Zambia needs technical assistance in reforming its regulatory framework and to effectively implement the WTO TBT and SPS agreements. The Zambia Bureau of Standards is the TBT Enquiry Point, but there has been insufficient public awareness of the services offered, and insufficient human resources.19

23. The ability to control SPS risks and meet international standards is key to Zambia's participation in the trading system, notably with regard to its non-traditional agricultural commodity exports but also in relation to raising its agricultural productivity and enhancing its domestic agricultural and food-safety levels. In 2006, the World Bank and USAID undertook a joint assessment to identify the most pressing and significant SPS management issues in Zambia, and provided recommendations related to plant health, food safety, and laboratory testing. 20 The assessment measured the performance of Zambia's national plant protection organization, the Plant Quarantine and Phytosanitary Service (PQPS) within the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, in relation to twelve core functions as identified by the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). Shortcomings of the PQPS included lack of effective surveillance and up-to-date pest lists; minimal capacities to carry out pest-risk analysis and inadequate human resource and financial allocation for the PQPS to adequately conduct its core functions. With regard to food safety, Zambia's main challenges include: a general low level of awareness of food safety; weak capacity to monitor and enforce existing laws on food safety; weak internal structures to provide oversight and information on food safety; lack of adequate training and guidelines for food safety inspection issues, and application of food safety and good hygiene or manufacturing practices within Zambian agriculture and agri- industry, which could pose production, commercial, and consumer risks in the future. Diagnostic testing capacity is important to assure buyers in importing countries that agricultural products from Zambia are compliant with established standards and to monitor and assess risks associated with pests and diseases and food-related contaminants in Zambia's domestic market. The assessment judged this capacity to be weak in most public-sector laboratories, with little coordination between them.

24. Several economically significant animal diseases (e.g. Foot and Mouth Disease, Swine Fever) are endemic in Zambia; this has a detrimental effect on smallholder farmers and on the potential for exports of livestock products. In July 2008, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) applied its tool for the Evaluation of Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS tool) to assist Zambia's veterinary services in identifying gaps and weaknesses, and establish key priorities to be addressed in order to comply with OIE international standards. The final report is under consideration by the Government.

25. A number of agencies and donors support SPS capacity building in Zambia, including the World Bank and USAID, FAO, UNIDO, and the Netherlands. In addition to national projects, Zambia

19 JITAP (2007). 20 World Bank (2006b).

WT/TPR/S/219 Trade Policy Review Page 81 benefits from various larger regional programmes funded by the EC. At SADC level, these include the Standards, Quality, Assurance, Accreditation and Metrology Programme (SQAM), Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD), capacity building on MRLs, and the promotion of regional integration in the livestock sector (PRINT). Zambia is also eligible under the Regional Standards Programme funded by DFID.

26. Regional EC-funded programmes with SPS elements at wider ACP level for which Zambia is eligible include the Pesticides Initiatives Programme (PIP) and the "Trade.com" programme, which focuses, inter alia, on implementation of WTO agreements and preparation of pilot projects with special attention to SPS/TBT issues. Also relevant is the Support Programme to Integrated National Action Plans for Avian and Human Influenza (SPINAP-AHI) aimed at strengthening capacity for early detection and rapid response to AHI. Planned EC-funded regional programmes at ACP-level include Participation of African Nations in Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standard Setting Organizations (PAN-SPSO) and Strengthening Food Safety Systems Through Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures. The latter will aim to establish risk-based food and feed safety systems for export products in ACP countries in line with regional, international, and EC standards.

27. Zambia's Diagnostic Trade Integration Study (DTIS) includes recommendations on safety and quality standards. The strengthening of Tier 2 of the Enhanced IF provides an avenue for funding of projects developed on the basis of SPS issues identified in the DTIS. Zambia has also benefited from the Standards and Trade Development Facility (STDF), a global programme in capacity building and technical cooperation.21 The objective of the STDF is to help developing countries and LDCs enhance their expertise and capacity to analyse and implement international SPS standards. Based on the findings of the IF DTIS, the STDF assisted in developing a project to address post-harvest contamination problems for paprika and groundnuts in Malawi and Zambia. The resultant project was integrated into UNIDO's Joint Trade Capacity Building Programme for Zambia. Discussions between UNIDO and NORAD to fund the project are ongoing.

28. In March 2008, Zambia submitted information to the WTO SPS Committee on its fruit fly situation, honey surveillance programme, and the operation of its SPS Enquiry Point.22 With the assistance of the US Department of Agriculture, Zambia had conducted fruit fly trapping using traps and lures; and in order to avoid restrictions in market access for Zambian organic honey, a survey was initiated to determine whether areas of Zambia were free from the American Foulbrood pathogen (Paenibacillus larvae subsp. larvae). A number of technical assistance projects (including JITAP) had facilitated the establishment and equipping of the national SPS Enquiry Point, making it fully operational. Zambia has not submitted any SPS notifications since 2000.

29. Zambia continues to benefit from technical assistance activities organized by the WTO and its partners. In 2007, Zambia hosted the WTO regional workshop on the SPS Agreement for English-speaking COMESA members. The workshop provided participants with good working knowledge of the provisions of the SPS Agreement – including the preparation of notifications – and the work of the three international standard-setting bodies, i.e. the Codex Alimentarius Commission, OIE and IPPC. Participants noted that some of the SPS challenges could also be addressed at the regional level, for example by adopting regional standards, where applicable, and setting up regional laboratories.

21 The STDF was established by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the World Organization for Animal Health, the World Bank, the World Health Organization, and the World Trade Organization (see: http://www.standardsfacility.org). 22 Paragraphs 15-16 of document G/SPS/R/49 and G/SPS/GEN/836.

Zambia WT/TPR/S/219 Page 82

(d) Notifications

30. Zambia needs assistance in meeting its notification requirements to the WTO. As is the case with many LDCs, notification requirements can be burdensome to Zambia. In addition, Zambia finds it difficult to coordinate notifications among the various government agencies.

(e) Customs valuation

31. Zambia has notified its implementation of the WTO Customs Valuation Agreement. Whilst it has taken measures to modernize its customs procedures, it still faces numerous challenges. These include complicated procedures and border clearance delays. Many of the shortcomings can be addressed under the overall umbrella of trade facilitation.

(f) Training of officials

32. Since its last TPR, Zambia has benefited from a number of WTO training courses for government officials. WTO training and technical assistance has focussed not only on building capacity to implement agreements but also on increasing the negotiating capacity of beneficiary countries in the context of the DDA negotiations and work programme. Zambian officials have benefited from: the 3-month trade policy courses held in the region and at the WTO; the 3-week introduction courses for LDCs; specialized courses on a number of WTO issues; and the regional trade negotiating courses. In addition, Zambia has benefited from the trainee and internship programmes organized by the WTO, aimed at enhancing the trainees' knowledge of the multilateral trading system, strengthening their understanding of the WTO, and enhancing the participation of their respective missions in the daily activities of the WTO. In particular, Zambia was a beneficiary of the Netherlands Trainee Programme in 2006. Zambia has also indicated an interest in the development of a university programme on the multilateral trading system with support from the WTO.

33. Despite the training provided, Zambia still needs assistance in enhancing trade capacity within government ministries and agencies involved in trade policy matters. A particular challenge is lack of capacity to collect and analyse data. In addition, Zambia needs continued assistance in the training of officials involved in: TRIPS-related matters; TBT and SPS; trade remedies; and Customs. The type of technical assistance needed in Zambia goes beyond the training of government officials on WTO- related subject matters, and includes technical assistance (both financial and technical) across all key sectors of the Zambian economy (energy, mining, tourism, manufacturing, transport) as well as the private sector.

WT/TPR/S/219 Trade Policy Review Page 83

REFERENCES

AfDB/OECD (2008), African Economic Outlook 2008: Zambia. Viewed at: http://www.oecd.org/ dataoecd/12/22/40578395.pdf.

Bank of Zambia (2008a), Annual Report 2007, Lusaka.

Bank of Zambia (2008b), Progress Report on the Implementation of the FSDP for the period July 2004 to June 2008, July, Lusaka.

Chilala, B., R. Munyaradzi and E. Marawa (2006), Southern Africa Global Competitiveness Hub: Draft Report on Assessment of Zambia's Capacity to Implement the Proposed Measures to Improve and Clarify Articles V, VIII and X on Trade Facilitation, June. Viewed at: http://www.satrade hub.org/assets/files/TF%20Zambia%20Summary%20Report%20for%20web.pdf.

Dun and Bradstreet (2006), Exporter's Encyclopaedia: Zambia, New York.

Economist Intelligence Unit (2008), Country Report: Zambia, London.

Foreign Investment Advisory Service (2004), Zambia: Analysis of the Legal and Regulatory Framework Underpinning Investment Environment, October. Viewed at: http://www.ifc.org/ ifcext/fias.nsf/AttachmentsByTitle/FIAS_Resources_Zambia_ReviewoftheLegalFramework(FY2005) /$FILE/Zambia+-+Review+of+the+Legal+Framework+-+Oct.2004.pdf.

Howell, Z., J. Stotsky and E. Ley (2002), "Tax Incentives for Business Investment: A Primer for Policy Makers in Developing Countries", World Development, Vol. 30.

IMF (2006), Fiscal Affairs Department, Zambia – Key issues for Tax Reform, October, Washington D.C.

IMF (2007a), Fiscal Affairs Department, Zambia – Key Issues of Tax Reform, March, Washington D.C.

IMF (2007b), Zambia: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper, Country Report No. 07/276. Viewed at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2007/cr07276.pdf.

IMF (2008a), De Facto Classification of Exchange Rate Regimes and Monetary Policy Frameworks. Viewed at: http://www.imf.org/external/np/mfd/er/2008/eng/0408.htm.

IMF (2008b), Zambia: Statistical Appendix, Country Report No. 08/30, January. Washington D.C.

IMF (2008c), Zambia – 2007 Article IV Consultation, Country Report No. 08/41, January. Viewed at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2008/cr0841.pdf.

IMF (2008d), Zambia: Letter of Intent, Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies, and Technical Memorandum of Understanding, May. Viewed at: http://www.imf.org/external/np/loi/ 2008/zmb/ 050708.pdf.

IMF (2008e), Zambia: Request for a Three-Year Arrangement Under the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility, Country Report No. 08/187, June. Viewed at: http://www.imf.org/external/ pubs/ft/scr/2008/ cr08187.pdf. Zambia WT/TPR/S/219 Page 84

IMF (2008f), Zambia – Selected Issues, Country Report No. 08/29, January. Viewed at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2008/ cr0829.pdf.

JITAP (2007), JITAP Final Report: Management Review, Zambia, December. Viewed at: http://www.jitap .org/reports/Zambia_country_report.pdf.

Lungu, J. (2008), "Copper Mining Agreements in Zambia: Renegotiation or Law Reform?", Review of African Political Economy, No. 117, ROAPE Publications Ltd. Viewed at: http://pdfserve. informaworld.com/887818_731278521_902154977.pdf.

Mattoo, Aaditya, and Lucy Payton (2007) (eds), Services Trade and Development: The Experience of Zambia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mattoo and Payton (2007), Telecommunications: the Persistence of Monopoly.

Millenium Challenge Corporation (2006), Millennium Challenge Account Threshold Program: Strategic Objective Grant Agreement between the USA and Zambia to Promote Economic Governance by Reducing Barriers to Trade and Investment, 22 May. Viewed at: http://www.mcc.gov/countries/zambia/Zambia_ SOAG.pdf.

Ministry of Finance and National Planning (2008), Annual FNDP Progress Report, Lusaka.

Ministry of Finance and National Planning (2009a), "2009 Budget Address", January. Viewed at: http://www.mofnp.gov.zm.

Ministry of Finance and National Planning (2009b), Economic Report 2008.

Mwase, Ngila (2008), "Coordination and Rationalization of Sub-Regional Economic Integration Institutions in Eastern and Southern Africa: SACU, SADC, EAC and COMESA", Journal of World Investment and Trade, April, Vol. 9, No. 2, Werner Publishing Company Ltd, Geneva.

OECD (1995), Taxation and Foreign Domestic Investment: The Experience of Economies in Transition, Paris.

Office of the United States Trade Representative (2008), Comprehensive Report on U.S. Trade and Investment Policy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa and Implementation of the African Growth and Opportunity Act. Viewed at: http://www.ustr.gov/assets/Trade_Development/Preference_Programs/ AGOA/asset_upload_file203 _14905.pdf.

Republic of Zambia (2006), Vision 2030 - A Prosperous Middle-Income Nation by 2030, December.

Tanzi and Shome (1992), "The Role of Taxation in the Development of East Asian Economies" in I. Takatoshi and A. O. Krueger (eds), The Political Economy of Tax Reform, University of Chicago Press.

Tokarick, S. (2006), "Does Import Protection Discourage Imports?", IMF Working paper WP/06/20, January, Washington, D.C.

Transparency International Zambia (2007), Show Me the Money: How Government Spends and Accounts for Public Money in Zambia. Viewed at: http://www.tizambia.org.zm/download/uploads/ Show_Me_ The_Money.pdf. WT/TPR/S/219 Trade Policy Review Page 85

Transparency International Zambia (2008). Viewed at: http://www.transparency.org/policy_ research/surveys_indices/cpi/2008/regional_highlights_ factsheets.

UNCTAD (2006), Investment Policy Review - Zambia, New York and Geneva. Viewed at: http://www.unctad.org/en/docs/iteipc200614_en.pdf.

UNDP (2007), Human Development Report 2007/08, New York.

U.S. Department of State (2009), Bureau of Economic, Energy and Business Affairs, 2009 Investment Climate Statement – Zambia, February. Viewed at: http://www.state.gov/e/eeb/rls/othr/ics/ 2009/117850.htm.

World Bank (2003), An Assessment of the Investment Climate in Zambia. Viewed at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTAFRSUMAFTPS/Resources/ICA004.pdf.

World Bank (2004), Zambia – Trade and Transport Facilitation Audit, June. Viewed at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTTLF/Resources/Zambia _Final_TTF_Report.pdf.

World Bank (2005a), "Summary of Zambia Investment Climate Assessment", Note No. 5, September. Viewed at: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/ default/WDSContent Server/WDSP/IB/2005/10/ 03/0000 90341_20051003144616/Rendered/PDF/336750AFTPS0note15.pdf.

World Bank (2005b), "Zambia - Diagnostic Trade Integration Study (DTIS)". Viewed at http://www.integratedframework.org/ files/English/Zambia_DTIS_10-10-05.pdf.

World Bank (2006a), Access to Financial Services in Zambia, J. De Luna Martinez, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4061, November.

World Bank (2006b), Zambia: SPS Management – Recommendations of a Joint World Bank/US AID Assessment Team, July. Viewed at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTRANETTRADE/ Resources/Topics/ Standards/Zambia_Summary_final_11Jul.pdf.

World Bank (2008a), Doing Business 2009: Country Profile for Zambia. Viewed at: http://www.doingbusiness.org/Documents/CountryProfiles/ZMB.pdf.

World Bank (2008b), Report No. 43352-ZM, Country Assistance Strategy for the Republic of Zambia, April. Viewed at: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/ WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/ 2008/04/30/000310607_200804 30135453/Rendered/PDF/43352mainoptmzd0CAS0IDA1R2008 10097.pdf.

World Bank (2008c), Report No. 44286-ZM, Zambia: What are the constraints to inclusive growth in Zambia? A Policy Note. Viewed at Viewed at: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/ WDSContent Server/WDSP/IB/2008/10/16/000333038_20081016032822/ Rendered/PDF/442860ESW0P11314 077B01OFF0USE0ONLY1.pdf.

World Bank (2008d), The Impact of Regional Liberalization and Harmonization in Road Transport Services: A Focus on Zambia and Lessons for Landlocked Counties, January, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4482.

World Bank (2008e), Zambia: Trade Brief. Viewed at: http://info.worldbank.org/etools/ wti2008/docs/brief209.pdf. Zambia WT/TPR/S/219 Page 86

World Economic Forum (2007), Africa - Competitiveness Report 2007, Washington D.C. Viewed at: http://www.weforum.org/pdf/gcr/africa/zambia.pdf.

WTO (2003), Trade Policy Review - Zambia, April, Geneva.

WTO, UNCTAD, ITC (2007), Joint Integrated Technical Assistance Programme (JITAP II) – JITAP II Final Report, Geneva.

Zambia Competition Commission, 2006 Annual Report.

Zambia Revenue Authority (2008), Annual Report 2007.