African-Americans Players Now Standouts in Baseball for Negative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Todd Frazier 2005

2021 RUTGERS BASEBALL 2021 ROSTER 2021 SCHEDULE UNIVERSITY ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS # Name Pos. Yr. Ht. Wt. B/T Hometown/High School (College) Location ......................... New Brunswick, N.J. Baseball Contact .... Jimmy Gill (10th Season) 1 Andy Axelson C R-So. 6-0 180 R/R Roxbury, N.J./Roxbury • Weekend of 3/5: at Minnesota (2) Founded ................................................ 1766 ....Associate Dir. of Athletic Communications w/ Indiana (2) Enrollment ......................................... 69,000 Email ...................... [email protected] 2 Kevin Welsh INF 5th-Sr. 5-9 175 S/R Columbus, N.J./Northern Burlington Regional President ......................... Jonathan Holloway Office Phone............................732-445-8103 3 Sam Owens C/INF R-Jr. 6-0 195 R/R Scituate, R.I./Scituate (Bryant) • Weekend of 3/12: at Maryland (4) Director of Athletics ......................Pat Hobbs Cell Phone ...............................732-991-9486 4 Tim Dezzi INF R-So. 5-11 190 R/R Mullica Hill, N.J./Clearview Regional (St. John’s) Nickname ...............................Scarlet Knights Office Location ......... Rutgers Athletic Center • Weekend of 3/19: Ohio State (3) Color ....................................................Scarlet Mailing Address .............83 Rockafeller Road 5 Danny DiGeorgio INF R-Jr. 6-5 210 R/R Staten Island, N.Y./Tottenville • Weekend of 3/26: at Purdue (3) Conference ......................................... Big Ten .....................................Piscataway, NJ 08854 6 Bradley Norton INF R-So. 6-1 185 R/R Pleasanton, Calif./Amador Valley (Ohlone CC/Nevada) Mascot .................................... Scarlet Knight 7 Peter Serruto C R-So. 6-2 195 R/R Short Hills, N.J./Millburn Website ...........................ScarletKnights.com • Weekend of 4/2: Penn State (3) FACT BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS 8 Mike Nyisztor INF/OF R-Jr. -

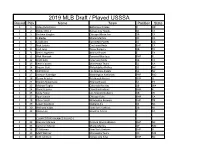

2019 MLB Draft / Played USSSA

2019 MLB Draft / Played USSSA Round Pick Name Team Position State 1 1 Adley Rutschman Baltimore Orioles C OR 1 2 Bobby Witt Jr Kansas City Royals SS TX 1 3 Andrew Vaughn Chicago White Sox 1B CA 1 4 JJ Bleday Miami Marlins OF PA 1 6 CJ Abrams San Diego Padres SS GA 1 7 Nick Lodolo Cincinnati Reds LHP CA 1 8 Josh Jung Texas Rangers 3B TX 1 9 Shea Langeliers Atlanta Braves C TX 1 11 Alek Manoah Toronto Blue Jays RHP FL 1 12 Brett Baty New York Mets 3B TX 1 13 Keoni Cavaco Minnesota Twins SS CA 1 14 Bryson Stott Philadelphia Phillies SS NV 1 15 Will Wilson Los Angeles Angels SS NC 1 17 Jackson Rutledge Washington Nationals RHP MO 1 18 Quinn Priester Pittsburgh Pirates RHP IL 1 21 Braden Shewmake Atlanta Braves SS TX 1 23 Michael Toglia Colorado Rockies 1B WA 1 24 Daniel Espino Cleveland Indians RHP FL 1 25 Kody Hoese Los Angeles Dodgers 3B IN 1 27 Ryan Jensen Chicago Cubs RHP CA 1 28 Ethan Small Milwaukee Brewers LHP TN 1 29 Logan Davidson Oakland A's SS NC 1 30 Anthony Volpe New York Yankees 2B NJ 1 32 Korey Lee Houston Astros C CA COMPETITIVE BALANCE ROUND 1 1 33 Brennan Malone Arizona Diamondbacks RHP NC 1 35 Kameron Misner Miami Marlins OF MO 1 38 TJ Sikkema New York Yankees LHP IL 1 39 Matt Wallner Minnesota Twins OF MN 1 40 Seth Johnson Tampa Bay Rays RHP NC 1 41 Davis Wendzel Texas Rangers 3B CA 30 of 41 = 73% 2 42 Gunnar Henderson Baltimore Orioles SS AL 2 43 Cameron Cannon Boston Red Sox SS AZ 2 44 Brady McConnell Kansas City Royals SS FL 2 45 Matthew Thompson Chicago White Sox RHP TX 2 46 Nasim Nunez Miami Marlins SS GA 2 47 Nick -

FINAL WEEK Save ^50 Htsicusswith Red Jets Firing

. Ill L . I I " ■ . ■ ■.'■'i'-','’'-■; ■ 'll . I TUESDAY, APRIL 6, 1968 The Weathw FACB 8IXTECT Averafs T h S j Net Prsaa Ron Fareeaat a# O. S. WBidlll Bar Ike Week EadeS Aptii s, issa Oeattag Sanight. law be rapraaanted would lOaa Deborah A. Bates Of 23 enter Uito an agreemeiU FOR About Town Tanner Bt. and Mias Kathleen Refuse Group Manchester, but that the bill 14,125 C. Vennart of 70 Weaver Rd. was being submitted to MtnSwr o f «he A«6tt were honored at a tea Thursday antes a district. If the NRDD Cosmetics Baieau a t CXreulndoe 0lanl«y Circle of South MeOi* at Southern Connecticut State Sets Meeting failed for lack of enabling legis College. The committee for the Church wW sponeor a rum- lation. ‘ IT'S MW niuveday at B a.m. Superior Student Progrram at Ttie four-town Northeart Ref Attembts will be made Thurs MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, APRIL 7, 1965 atOooper Hall. the college sponsored the tea use Disposal District (NRDD), day ulgnt to mollify hurt feel VOL. LXXXIvi NO. 169 (THIRTY-TWO PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) for 60 frsehmen who achieved ings and to patch up differences. consisting of Manchester, Ver RadMUian Seaman Appren a 3.2 point average out of a pos If they fail, thia may be the Uggeits tice Richard L. Getsewich, son sible 4.0. non, South Windsor and Bolton, last meeting fW the fcur towns. «( Mr. and Mra Richard P. Oet- wfll meet si 7:45 p.m. Thurs At The Parkadt nearich a t S7l Hartford Rd., is a His Sixth Words: 'I t la fin day in the Muidclpal Building MANCHESTER crew member of the dertroyer ished," will be the theme of the Hearing Room to decide Us fu Damages Heavy Comsat Satellite U8S Flake while undersoins re Ijenten program for senior high fresher training at Ouantanamo on Thursday at 7 a.m. -

Clips for 7-12-10

MEDIA CLIPS – July 24th, 2018 Inbox: Should Rox pursue reliever at Deadline? Beat reporter Thomas Harding answers questions from Colorado fans By Thomas Harding MLB.com @harding_at_mlb Jul. 23rd, 2018 DENVER -- The most likely way the Rockies will pick to keep their surge going is to improve the bullpen by the July 31 non-waiver Trade Deadline -- or at least that's the way I'm answering the first question in the Edward Jones Beat Reporter's Inbox. Thomas Harding ✔@harding_at_mlb Please tweet me here with your questions for the next @EdwardJones #Rockies Beat Reporter's Inbox. Eric Swanson@Eric_C_Swanson With all the money spent on the bullpen this offseason, yet it still seems to be a need for this team; is there any chance they make a move to acquire a reliever at the deadline? 7:08 AM - Jul 23, 2018 This question is the biggest one that the Rockies are likely to address. In doing so, let's address exactly what the need is. First, I'll determine what's pertinent, and any stat for any reliever that takes into account the season is not. I'm going to look at the Rockies' bullpen starting June 28, the beginning of the club's current 15-4 run. The full bullpen is 7- 2 with a 3.34 ERA over that period, but even that doesn't tell us the exact areas of strength and need. 1 Let's zero in on key individuals, working from the ninth inning to earlier innings (more or less), starting June 28: • Closer Wade Davis: nine innings pitched, 1.00 ERA, .129 batting average against, 11 strikeouts, two walks • Righty Adam Ottavino: 10 2/3 IP, 3.38 ERA, .318 BAA, 14 SO, 5 BB • Righty Scott Oberg: 10 IP, 1.80 ERA, .278 BAA, 10 SO, 1 BB • Righty Bryan Shaw: 4 1/3 IP (since his return from a right calf strain), 2.08 ERA, .188 BAA, 6 SO, 2 BB • Lefty Chris Rusin: 7 1/3 IP, 6.14 ERA, .323 BAA, 4 SO, 3 BB • Lefty Jake McGee: 5 2/3 IP, 6.35 ERA, .273 BA, 6 SO, 3 BB (.905 OPS against) So this gives the Rockies two ways to shore up the back end of the bullpen. -

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

2011 Topps Gypsy Queen Baseball

Hobby 2011 TOPPS GYPSY QUEEN BASEBALL Base Cards 1 Ichiro Suzuki 49 Honus Wagner 97 Stan Musial 2 Roy Halladay 50 Al Kaline 98 Aroldis Chapman 3 Cole Hamels 51 Alex Rodriguez 99 Ozzie Smith 4 Jackie Robinson 52 Carlos Santana 100 Nolan Ryan 5 Tris Speaker 53 Jimmie Foxx 101 Ricky Nolasco 6 Frank Robinson 54 Frank Thomas 102 David Freese 7 Jim Palmer 55 Evan Longoria 103 Clayton Richard 8 Troy Tulowitzki 56 Mat Latos 104 Jorge Posada 9 Scott Rolen 57 David Ortiz 105 Magglio Ordonez 10 Jason Heyward 58 Dale Murphy 106 Lucas Duda 11 Zack Greinke 59 Duke Snider 107 Chris V. Carter 12 Ryan Howard 60 Rogers Hornsby 108 Ben Revere 13 Joey Votto 61 Robin Yount 109 Fred Lewis 14 Brooks Robinson 62 Red Schoendienst 110 Brian Wilson 15 Matt Kemp 63 Jimmie Foxx 111 Peter Bourjos 16 Chris Carpenter 64 Josh Hamilton 112 Coco Crisp 17 Mark Teixeira 65 Babe Ruth 113 Yuniesky Betancourt 18 Christy Mathewson 66 Madison Bumgarner 114 Brett Wallace 19 Jon Lester 67 Dave Winfield 115 Chris Volstad 20 Andre Dawson 68 Gary Carter 116 Todd Helton 21 David Wright 69 Kevin Youkilis 117 Andrew Romine 22 Barry Larkin 70 Rogers Hornsby 118 Jason Bay 23 Johnny Cueto 71 CC Sabathia 119 Danny Espinosa 24 Chipper Jones 72 Justin Morneau 120 Carlos Zambrano 25 Mel Ott 73 Carl Yastrzemski 121 Jose Bautista 26 Adrian Gonzalez 74 Tom Seaver 122 Chris Coghlan 27 Roy Oswalt 75 Albert Pujols 123 Skip Schumaker 28 Tony Gwynn Sr. 76 Felix Hernandez 124 Jeremy Jeffress 2929 TTyy Cobb 77 HHunterunter PPenceence 121255 JaJakeke PPeavyeavy 30 Hanley Ramirez 78 Ryne Sandberg 126 Dallas -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Cubs Daily Clips

April 6, 2016 CSNChicago.com, After all the hype, Jon Lester ready to roll with Cubs http://www.csnchicago.com/cubs/jon-lester-already-showing-noticeable-progression-year-2-cubs CSNChicago.com, Cubs will face some interesting decisions with Jorge Soler http://www.csnchicago.com/cubs/cubs-will-face-some-interesting-decisions-jorge-soler CSNChicago.com, Back with Cubs, Dexter Fowler playing like he has something to prove http://www.csnchicago.com/cubs/back-cubs-dexter-fowler-playing-he-has-something-prove Chicago Tribune, Jon Lester regains old form in leading Cubs to 6-1 victory over Angels http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-jon-lester-report-cubs-angels-spt-0406-20160405- story.html Chicago Tribune, Cubs may be baseball's first team with its own laugh track http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/columnists/ct-cubs-silliness-sullivan-spt-0406-20160405-column.html Chicago Tribune, Joe Maddon's iPad gets early season workout http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-joe-maddons-ipad-gets-early-season-workout- 20160405-story.html Chicago Tribune, Cubs' Matt Szczur stays compact but provides big results http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-matt-szczur-plays-big-20160405-story.html Chicago Tribune, Tuesday's recap: Cubs 6, Angels 1 http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-gameday-cubs-angels-spt-0406-20160405- story.html Chicago Tribune, Cubs prospect Duane Underwood Jr. playing catch-up http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-duane-underwood-jr-healing-20160406-story.html -

Winter League AL Player List

American League Player List: 2020-21 Winter Game Pitchers 1988 IP ERA 1989 IP ERA 1990 IP ERA 1991 IP ERA 1 Dave Stewart R 276 3.23 258 3.32 267 2.56 226 5.18 2 Roger Clemens R 264 2.93 253 3.13 228 1.93 271 2.62 3 Mark Langston L 261 3.34 250 2.74 223 4.40 246 3.00 4 Bob Welch R 245 3.64 210 3.00 238 2.95 220 4.58 5 Jack Morris R 235 3.94 170 4.86 250 4.51 247 3.43 6 Mike Moore R 229 3.78 242 2.61 199 4.65 210 2.96 7 Greg Swindell L 242 3.20 184 3.37 215 4.40 238 3.48 8 Tom Candiotti R 217 3.28 206 3.10 202 3.65 238 2.65 9 Chuck Finley L 194 4.17 200 2.57 236 2.40 227 3.80 10 Mike Boddicker R 236 3.39 212 4.00 228 3.36 181 4.08 11 Bret Saberhagen R 261 3.80 262 2.16 135 3.27 196 3.07 12 Charlie Hough R 252 3.32 182 4.35 219 4.07 199 4.02 13 Nolan Ryan R 220 3.52 239 3.20 204 3.44 173 2.91 14 Frank Tanana L 203 4.21 224 3.58 176 5.31 217 3.77 15 Charlie Leibrandt L 243 3.19 161 5.14 162 3.16 230 3.49 16 Walt Terrell R 206 3.97 206 4.49 158 5.24 219 4.24 17 Chris Bosio R 182 3.36 235 2.95 133 4.00 205 3.25 18 Mark Gubicza R 270 2.70 255 3.04 94 4.50 133 5.68 19 Bud Black L 81 5.00 222 3.36 207 3.57 214 3.99 20 Allan Anderson L 202 2.45 197 3.80 189 4.53 134 4.96 21 Melido Perez R 197 3.79 183 5.01 197 4.61 136 3.12 22 Jimmy Key L 131 3.29 216 3.88 155 4.25 209 3.05 23 Kirk McCaskill R 146 4.31 212 2.93 174 3.25 178 4.26 24 Dave Stieb R 207 3.04 207 3.35 209 2.93 60 3.17 25 Bobby Witt R 174 3.92 194 5.14 222 3.36 89 6.09 26 Brian Holman R 100 3.23 191 3.67 190 4.03 195 3.69 27 Andy Hawkins R 218 3.35 208 4.80 158 5.37 90 5.52 28 Todd Stottlemyre -

Baltimore Orioles Game Notes

BALTIMORE ORIOLES GAME NOTES ORIOLE PARK AT CAMDEN YARDS • 333 WEST CAMDEN STREET • BALTIMORE, MD 21201 THURSDAY, MAY 24, 2018 • GAME #50 • ROAD GAME #27 BALTIMORE ORIOLES (15-34) at CHICAGO WHITE SOX (15-31) RHP Dylan Bundy (2-6, 4.70) vs. RHP Lucas Giolito (3-4, 6.42) WHAT A DIFFERENCE A DAY MAKES: RHP Dylan Bundy makes his fi fth day-game start of the season...He has gone 1-1 with a 0.70 MAN-NY OF THE YEAR ERA (2 ER/25.2 IP) in four starts during the daytime this season...His 0.70 daytime ERA leads the majors (min. three daytime starts)...In Manny Machado’s current AL and MLB ranks: his career, Bundy has gone 6-6 with a 4.75 ERA (57 ER/108.0 IP) in 25 career day games (17 starts). Batting Average (.328) 4th AL 6th MLB Home Runs (15) T-2nd AL T-2nd MLB DOUBLE DARE: LF Trey Mancini notched two outfi eld assists in the bottom of the fi fth inning on Monday night at Chicago...According to RBI (43) 1st AL 1st MLB the Elias Sports Bureau, Mancini is one of just two players in Orioles history (since 1954) with two outfi eld assists in the same inning (also Hits (62) T-3rd AL T-4th MLB LF Don Buford on June 25, 1970 at Boston in the fi rst inning)...According to STATS, LLC., the last player in the majors with two outfi eld Extra-base Hits (28) T-2nd AL T-3rd MLB assists in the same inning was LF José Osuna of the Pittsburgh Pirates, who did so on July 6, 2017 at Philadelphia in the second inning.. -

2010 Topps Baseball Set Checklist

2010 TOPPS BASEBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Prince Fielder 2 Buster Posey RC 3 Derrek Lee 4 Hanley Ramirez / Pablo Sandoval / Albert Pujols LL 5 Texas Rangers TC 6 Chicago White Sox FH 7 Mickey Mantle 8 Joe Mauer / Ichiro / Derek Jeter LL 9 Tim Lincecum NL CY 10 Clayton Kershaw 11 Orlando Cabrera 12 Doug Davis 13 Melvin Mora 14 Ted Lilly 15 Bobby Abreu 16 Johnny Cueto 17 Dexter Fowler 18 Tim Stauffer 19 Felipe Lopez 20 Tommy Hanson 21 Cristian Guzman 22 Anthony Swarzak 23 Shane Victorino 24 John Maine 25 Adam Jones 26 Zach Duke 27 Lance Berkman / Mike Hampton CC 28 Jonathan Sanchez 29 Aubrey Huff 30 Victor Martinez 31 Jason Grilli 32 Cincinnati Reds TC 33 Adam Moore RC 34 Michael Dunn RC 35 Rick Porcello 36 Tobi Stoner RC 37 Garret Anderson 38 Houston Astros TC 39 Jeff Baker 40 Josh Johnson 41 Los Angeles Dodgers FH 42 Prince Fielder / Ryan Howard / Albert Pujols LL Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Marco Scutaro 44 Howie Kendrick 45 David Hernandez 46 Chad Tracy 47 Brad Penny 48 Joey Votto 49 Jorge De La Rosa 50 Zack Greinke 51 Eric Young Jr 52 Billy Butler 53 Craig Counsell 54 John Lackey 55 Manny Ramirez 56 Andy Pettitte 57 CC Sabathia 58 Kyle Blanks 59 Kevin Gregg 60 David Wright 61 Skip Schumaker 62 Kevin Millwood 63 Josh Bard 64 Drew Stubbs RC 65 Nick Swisher 66 Kyle Phillips RC 67 Matt LaPorta 68 Brandon Inge 69 Kansas City Royals TC 70 Cole Hamels 71 Mike Hampton 72 Milwaukee Brewers FH 73 Adam Wainwright / Chris Carpenter / Jorge De La Ro LL 74 Casey Blake 75 Adrian Gonzalez 76 Joe Saunders 77 Kenshin Kawakami 78 Cesar Izturis 79 Francisco Cordero 80 Tim Lincecum 81 Ryan Theroit 82 Jason Marquis 83 Mark Teahen 84 Nate Robertson 85 Ken Griffey, Jr. -

Want and Bait 11 27 2020.Xlsx

Year Maker Set # Var Beckett Name Upgrade High 1967 Topps Base/Regular 128 a $ 50.00 Ed Spiezio (most of "SPIE" missing at top) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 149 a $ 20.00 Joe Moeller (white streak btwn "M" & cap) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 252 a $ 40.00 Bob Bolin (white streak btwn Bob & Bolin) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 374 a $ 20.00 Mel Queen ERR (underscore after totals is missing) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 402 a $ 20.00 Jackson/Wilson ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 427 a $ 20.00 Ruben Gomez ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 447 a $ 4.00 Bo Belinsky ERR (incomplete stat line) 1968 Topps Base/Regular 400 b $ 800 Mike McCormick White Team Name 1969 Topps Base/Regular 47 c $ 25.00 Paul Popovich ("C" on helmet) 1969 Topps Base/Regular 440 b $ 100 Willie McCovey White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 447 b $ 25.00 Ralph Houk MG White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 451 b $ 25.00 Rich Rollins White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 511 b $ 25.00 Diego Segui White Letters 1971 Topps Base/Regular 265 c $ 2.00 Jim Northrup (DARK black blob near right hand) 1971 Topps Base/Regular 619 c $ 6.00 Checklist 6 644-752 (cprt on back, wave on brim) 1973 Topps Base/Regular 338 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 1973 Topps Base/Regular 588 $ 20.00 Checklist 529-660 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 263 $ 3.00 Checklist 133-264 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 273 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 upgrd exmt+ 1956 Topps Pins 1 $ 500 Chuck Diering SP 1956 Topps Pins 2 $ 30.00 Willie Miranda 1956 Topps Pins 3 $ 30.00 Hal Smith 1956 Topps Pins 4 $