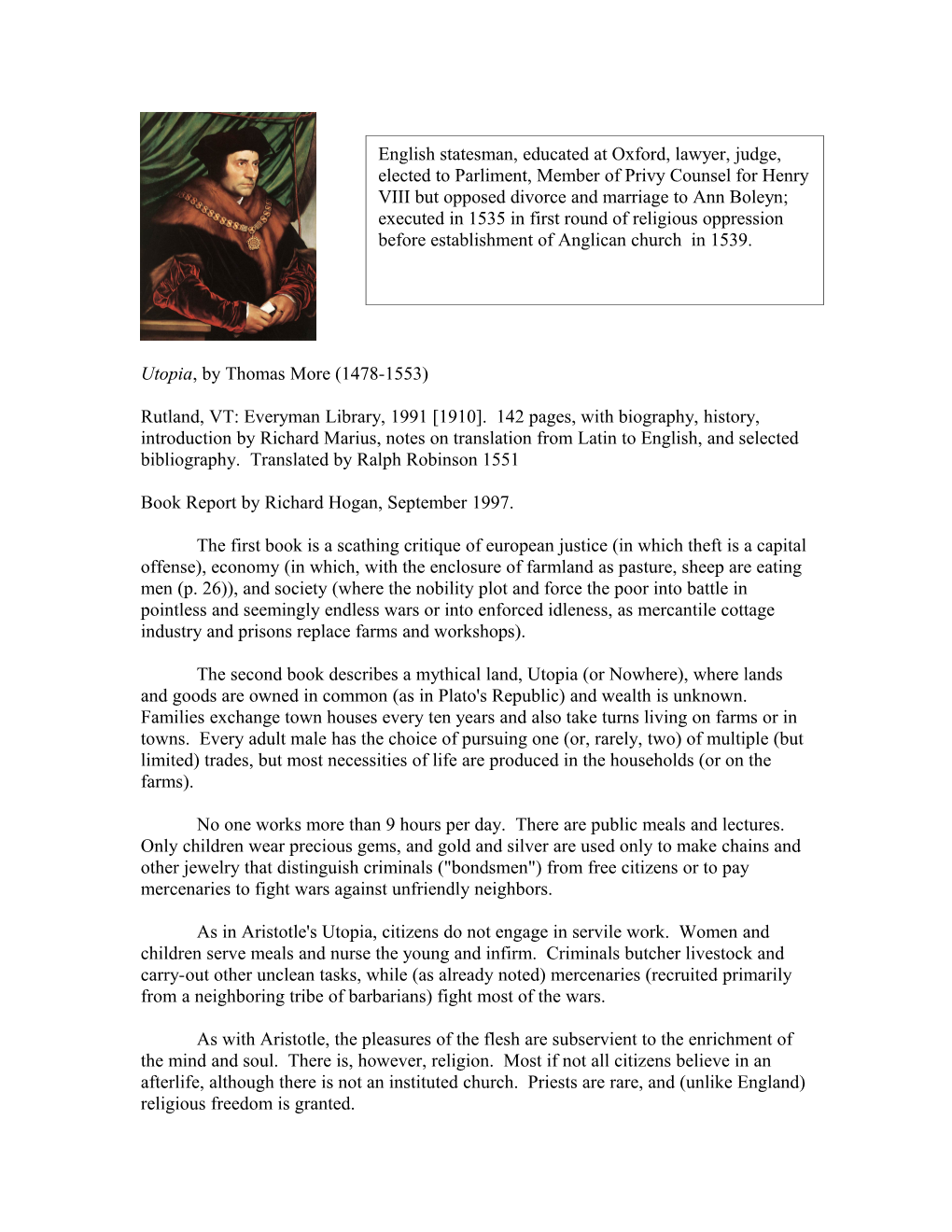

English statesman, educated at Oxford, lawyer, judge, elected to Parliment, Member of Privy Counsel for Henry VIII but opposed divorce and marriage to Ann Boleyn; executed in 1535 in first round of religious oppression before establishment of Anglican church in 1539.

Utopia, by Thomas More (1478-1553)

Rutland, VT: Everyman Library, 1991 [1910]. 142 pages, with biography, history, introduction by Richard Marius, notes on translation from Latin to English, and selected bibliography. Translated by Ralph Robinson 1551

Book Report by Richard Hogan, September 1997.

The first book is a scathing critique of european justice (in which theft is a capital offense), economy (in which, with the enclosure of farmland as pasture, sheep are eating men (p. 26)), and society (where the nobility plot and force the poor into battle in pointless and seemingly endless wars or into enforced idleness, as mercantile cottage industry and prisons replace farms and workshops).

The second book describes a mythical land, Utopia (or Nowhere), where lands and goods are owned in common (as in Plato's Republic) and wealth is unknown. Families exchange town houses every ten years and also take turns living on farms or in towns. Every adult male has the choice of pursuing one (or, rarely, two) of multiple (but limited) trades, but most necessities of life are produced in the households (or on the farms).

No one works more than 9 hours per day. There are public meals and lectures. Only children wear precious gems, and gold and silver are used only to make chains and other jewelry that distinguish criminals ("bondsmen") from free citizens or to pay mercenaries to fight wars against unfriendly neighbors.

As in Aristotle's Utopia, citizens do not engage in servile work. Women and children serve meals and nurse the young and infirm. Criminals butcher livestock and carry-out other unclean tasks, while (as already noted) mercenaries (recruited primarily from a neighboring tribe of barbarians) fight most of the wars.

As with Aristotle, the pleasures of the flesh are subservient to the enrichment of the mind and soul. There is, however, religion. Most if not all citizens believe in an afterlife, although there is not an instituted church. Priests are rare, and (unlike England) religious freedom is granted. Utopia is, in short, a communalist religious community, patriarchal and governed by elected elders (aristocrats), a prince who serves for life (unless recalled by the citizens) and lesser officials who are elected annually. The sinners do the necessary servile work, the numerous middle class works on farms and in shops, and only the prince and the priests are not engaged in productive enterprise.