YEAR SEVEN HISTORY: LOCAL HISTORY The battle of Vinegar Hill

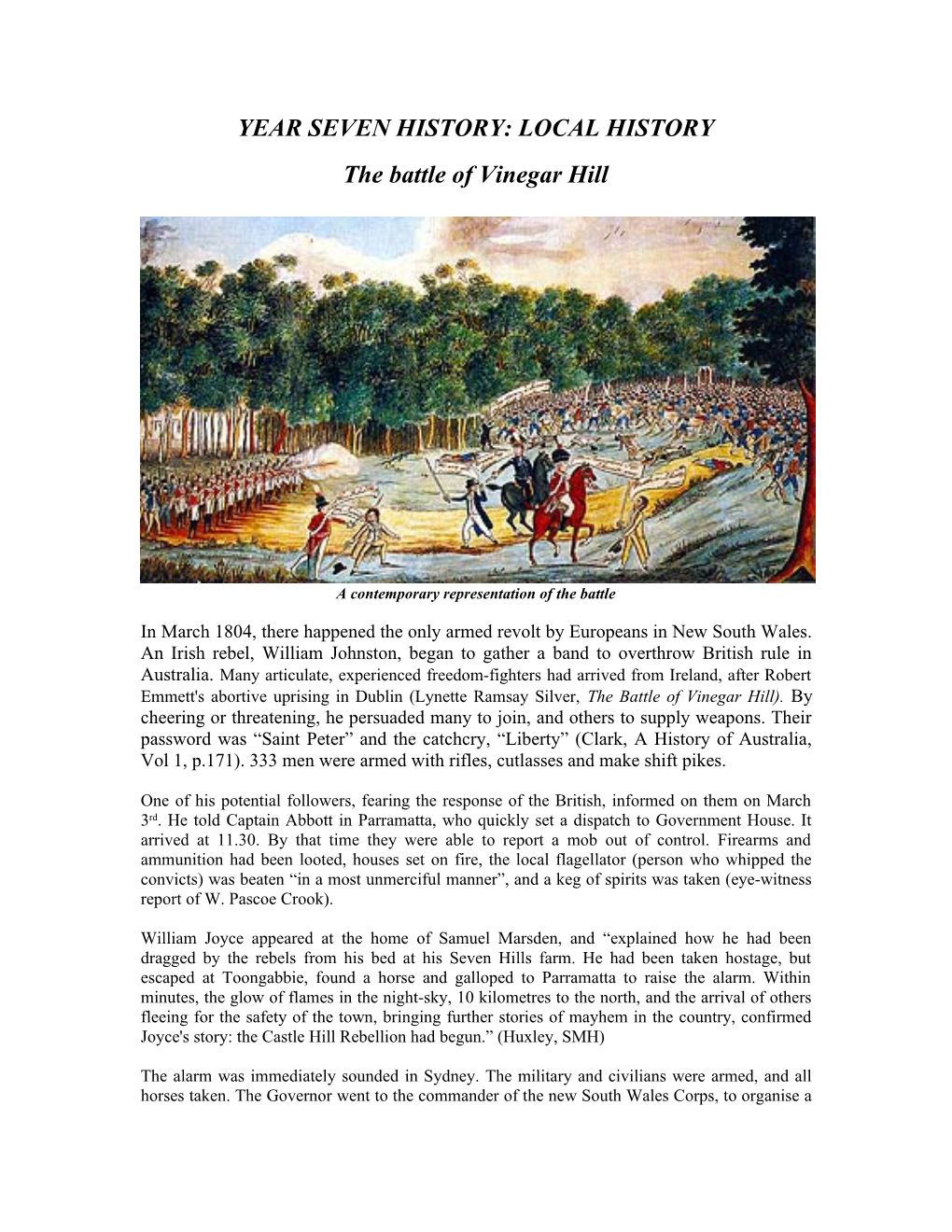

A contemporary representation of the battle

In March 1804, there happened the only armed revolt by Europeans in New South Wales. An Irish rebel, William Johnston, began to gather a band to overthrow British rule in Australia. Many articulate, experienced freedom-fighters had arrived from Ireland, after Robert Emmett's abortive uprising in Dublin (Lynette Ramsay Silver, The Battle of Vinegar Hill). By cheering or threatening, he persuaded many to join, and others to supply weapons. Their password was “Saint Peter” and the catchcry, “Liberty” (Clark, A History of Australia, Vol 1, p.171). 333 men were armed with rifles, cutlasses and make shift pikes.

One of his potential followers, fearing the response of the British, informed on them on March 3rd. He told Captain Abbott in Parramatta, who quickly set a dispatch to Government House. It arrived at 11.30. By that time they were able to report a mob out of control. Firearms and ammunition had been looted, houses set on fire, the local flagellator (person who whipped the convicts) was beaten “in a most unmerciful manner”, and a keg of spirits was taken (eye-witness report of W. Pascoe Crook).

William Joyce appeared at the home of Samuel Marsden, and “explained how he had been dragged by the rebels from his bed at his Seven Hills farm. He had been taken hostage, but escaped at Toongabbie, found a horse and galloped to Parramatta to raise the alarm. Within minutes, the glow of flames in the night-sky, 10 kilometres to the north, and the arrival of others fleeing for the safety of the town, bringing further stories of mayhem in the country, confirmed Joyce's story: the Castle Hill Rebellion had begun.” (Huxley, SMH)

The alarm was immediately sounded in Sydney. The military and civilians were armed, and all horses taken. The Governor went to the commander of the new South Wales Corps, to organise a company of troops to meet the rebels. He arrived at Parramatta at 4 am. Johnson and the NSW Corps arrived at 5 am. Governor King, ordered all rebels to give themselves up within 24 hours (Clark, p.172). Further, he declared anyone seen out of doors after sunset would be treated as a rebel “and punished accordingly”. His proclaimation had Parramatta, Castle Hill, Toongabbie, Prospect, Seven Hills, Baulkham Hills, Hawkesbury and Nepean districts in a state of rebellion, and therefore martial law (Proclaimation by Governor King, 5th March 1804).

By then, panic had set in at Parramatta, and its 1700 residents. “(W)ithin hours an advance mob of insurgents could be heard and - more frightening in the pitch-dark night, seen - massing at the West Gate, waving torches, only a few hundred metres from Government House. "You can have no idea what a dreadful night it was and what we suffered in our minds," Mrs Marsden recorded. While she, her husband and their terrified guest joined other residents preparing to escape by river boat to Sydney, the beat of drums and gunfire punctuated the humid night air, as soldiers were called to arms and able-bodied men were summoned to the defence of the town” (Huxley, SMH).

The NSW Corps (25 NCOs and privates), under Johnston and Laycock, his quarter-master, found the rebels 11 kms out of Toongabbie, at Vinegar Hill. Their advantages of surprise had not been used effectively. The Macarthurs' Elizabeth Farm had not been taken. So there was no need to divert troops there. The Parramatta mob failed to take out the garrison there. The “recruitment of disaffected local patriots and volunteers from the Hawkesbury area - unravelled amid confusion created by a mix of ill-fortune and betrayal, communication problems and sheer incompetence” (Huxley, SMH).

From contemporary records, Silver concludes that both sides would already have been on the move for several hours as they pressed along the Old Windsor Road in scorching heat on the morning of Monday, March 5. Though the rebels may have regretted their premature celebration drinks, they were at least lightly clad. By contrast, the 29 troops, their numbers swollen by about 50 civilians, would have been wearing "heavy, red woollen tunics, thick breeches and all the customary paraphernalia". About midmorning, and after a 15-kilometre pursuit, Major Johnston's force finally caught up with the rebels on an unnamed piece of high ground, described only as the "second hill on this [the Parramatta] side of the Last Half Way Pond". A memorial in the Castlebrook Cemetery grounds marks the approximate spot.

Twice, as much to delay the rebels as persuade them to surrender, Major Johnston sent emissaries - first, trooper Thomas Anlezark and, a little later, Catholic priest Father James Dixon - ahead on horseback to talk to the rebels. Finally, about 11am, he and Dixon returned seemingly determined to force the issue. The rebel leaders Cunningham and William Johnston emerged, repeating their demand for "Death or liberty ... and a ship to take us home".

Instead, Major Johnston and Anlezark - who had suddenly returned to his commanding officer's side - pulled pistols, placed them to the heads of the two rebel leaders and marched the two men back towards the lines of the Redcoats, who were ordered to charge and fire. The numbers were with the rebels, whose force of about 230 easily outnumbered the 29 soldiers and 50 or so armed civilians. But they were leaderless, caught completely unawares and totally unprepared by what they saw as an act of dupliticity, says Silver.

"Their pathetic home-made pikes and pitchforks and their weird collection of guns and ammunition were no match for the mercilessly repetitive load, aim, fire technique of the contingent of well-trained King's men." It was probably all over in less than 30 minutes. Many rebels were felled, others fled. Several were arrested and, though Major Johnston sought to stop bloodshed, 15 in all were killed on the battlefield. Those who survived were pursued towards the Hawkesbury until "excessive dark" night fell. More than 30 rebels were flogged and sent into exile. Nine were executed, including William Johnston, whose corpse was hanged in chains on the Prospect roadside, near Parramatta, and co-leader Cunningham, who was hanged without trial that night at Green Hills, modern-day Windsor. (Huxley , SMH)

References Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol 5, 1803-5. Clark, A History of Australia, Vol 1 Huxley, The Battle of Vinegar Hill, SMH 28 February, 2004 Lynette Ramsay Silver, The Battle of Vinegar Hill

Questions: 1. What suggests that the battle was an Irish attempt to gain independence from Britain? 2. What evidence suggests there were problems with the rebellion from the outset? 3. Why would Marsden believe Joyce? 4. How did Governor King react? 5. How did Marsden react? 6. By what date did much of Western Sydney get its current name? 7. What had the rebels failed to do, by the time they met the NSW Corps? 8. Was the rebellion a mix of ill-fortune and betrayal, communication problems and sheer incompetence? 9. What disadvantages did the Government side have? 10. What advantages did they have? 11. What disadvantages did the rebels have? 12. What advantages did they have? 13. How did Johnston take advantage of the rebels? 14. Why do you think they were taken in? 15. How were they treated after the battle? 16. Look at the picture. How well does it support the written evidence?