Jude Analysis

Textual Variants Wasserman has written a 416 page book outlining all the textual variants in Jude from 560 Greek manuscripts. However, only 15 of these are covered in Metzger’s Textual Commentary on the New Testament. 18 textual variants are covered in this analysis.

1 is found only in Tyndale (1536) and the Bishops Bible (1568) 2 are found only in KJV (1611) 3 are found only in KJV (1611) and Bloomfield (1839 Church of England) 6 are found only in Majority Text readings

That leaves just 6 that do not depend on whether a Majority text approach is taken, and one of these has three variants, one of which is only found in Majority text readings.

The Majority Text readings are in the KJV and Bloomfield, but are also followed by the NKJV (1982) and recent Greek texts that opt for a Majority text approach, as opposed to the eclectic approach used by most recent translations. Therefore the choice between a Majority text approach and an eclectic approach is important in deciding the basis for the text.

For readers in the internet age, this takes on greater significance. Most free commentaries on the internet will be older and will be based on Majority text readings. Also, a number of study bibles, follow the NKJV, including Andrews SB (Seventh Day Adventist), New Spirit-Filled Life SB (Pentecostal), Revival SB (Pentecostal) and Word in Life SB.

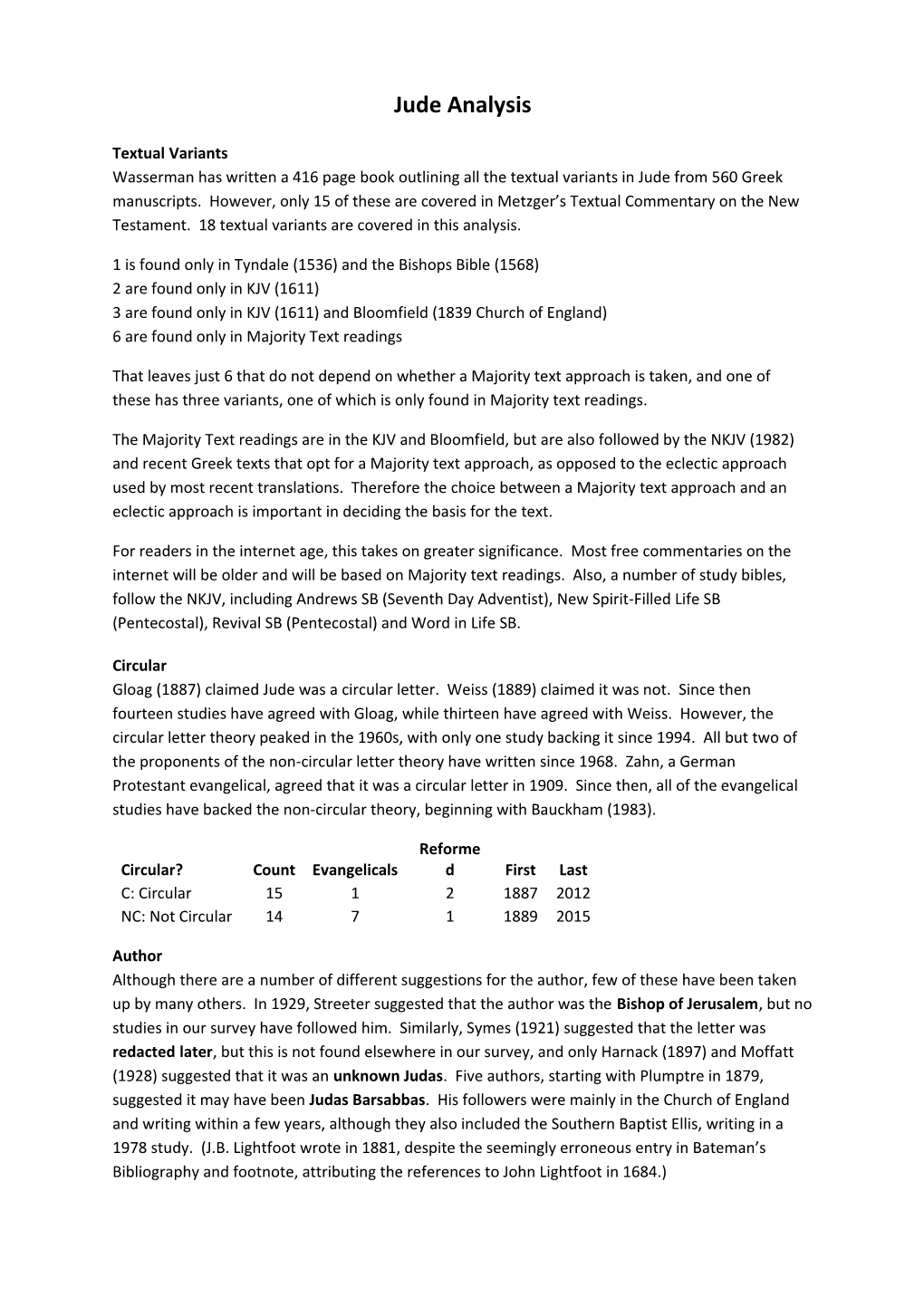

Circular Gloag (1887) claimed Jude was a circular letter. Weiss (1889) claimed it was not. Since then fourteen studies have agreed with Gloag, while thirteen have agreed with Weiss. However, the circular letter theory peaked in the 1960s, with only one study backing it since 1994. All but two of the proponents of the non-circular letter theory have written since 1968. Zahn, a German Protestant evangelical, agreed that it was a circular letter in 1909. Since then, all of the evangelical studies have backed the non-circular theory, beginning with Bauckham (1983).

Reforme Circular? Count Evangelicals d First Last C: Circular 15 1 2 1887 2012 NC: Not Circular 14 7 1 1889 2015

Author Although there are a number of different suggestions for the author, few of these have been taken up by many others. In 1929, Streeter suggested that the author was the Bishop of Jerusalem, but no studies in our survey have followed him. Similarly, Symes (1921) suggested that the letter was redacted later, but this is not found elsewhere in our survey, and only Harnack (1897) and Moffatt (1928) suggested that it was an unknown Judas. Five authors, starting with Plumptre in 1879, suggested it may have been Judas Barsabbas. His followers were mainly in the Church of England and writing within a few years, although they also included the Southern Baptist Ellis, writing in a 1978 study. (J.B. Lightfoot wrote in 1881, despite the seemingly erroneous entry in Bateman’s Bibliography and footnote, attributing the references to John Lightfoot in 1684.) That leaves just two suggestions: the brother of Jesus and James (64 studies), and Pseudonymity (46 studies). Evangelicals prefer the former, with only one evangelical suggesting Pseudonymity. Evangelical Author Count s Reformed First Last Ba: Judas Barsabbas 5 1 0 1879 1978 Bi: Bishop of Jerusalem 1 0 0 1929 1929 Br: James' Brother 64 18 9 1551 2015 Ps: Pseudonymous 46 1 3 1894 2010 Re: Redacted Later 1 0 0 1921 1921 Th: Thomas 2 0 0 1967 1982 Un: Unknown Judas 2 1 0 1897 1928

Origin Sixteen studies suggested that the place of origin is unknown, including just two evangelicals. Just three studies suggested Syria, the last of which was published in 1982, and seven have suggested Egypt, beginning with Julicher in 1904. Most of the later authors suggesting Egypt have also written in German, and there are no Evangelicals among them, whereas seven of the eighteen studies suggesting Judea were by evangelicals.

Origin Count Evangelicals Reformed First Last E: Egypt 7 0 1 1904 1992 J: Judea 18 7 5 1887 2015 S: Syria 3 0 0 1967 1982 Un: Unknown 16 2 3 1901 2005

Recipients Of those who describe the recipients, twenty suggest a Gentile audience, twenty-nine suggest a Jewish audience and six suggest a mixed audience. The mixed audience suggestion was only found from Schneider in 1961 to Bauckham in 1983, and then again in Schreiner in 2003. The Jewish audience suggestion is found from 1877 to 2015, and the Gentile audience suggestion is found from 1899 to 2002. Lenski is the only evangelical suggesting a Gentile audience, while nine evangelicals suggest a Jewish audience, and three suggest a mixed audience.

Reforme Recipients Count Evangelicals d First Last G: Gentile 20 1 0 1899 2002 J: Jewish 29 9 7 1883 2015 M: Mixed 6 3 0 1961 2003

Destination A number of destinations have been suggested for the letter. Davidson (1894) suggested Syrian Antioch, and eight of our studies followed him until 1935, followed by four more between 1960 and 2003. Julicher (1904) suggested Alexandria, and was followed by six studies, ending in 1993. Each of these suggestions was made by just one evangelical. Huther (1877) suggested Asia Minor, and was followed by eight studies, ending in 2003. Thirteen studies published between 1907 and 2005 explicitly suggested that the destination was unknown. Each of these two suggestions was made by two evangelicals. Keil (1883) suggested Judea, which is the most common suggestion, with ten of the fourteen studies between 1986 and 2015, including six evangelicals, while Davidson’s more general suggestion of a Gentile area (1894), has been followed by thirteen studies, eight of which were published between 1974 and 2012, including five evangelicals. Evangelical Destination Count s Reformed First Last Al: Alexandria 7 1 0 1904 1993 AM: Asia Minor 9 2 1 1877 2003 GA: Gentile Area 13 5 3 1894 2012 J: Judea 14 6 3 1883 2015 SA: Syrian Antioch 13 1 1 1897 2003 Un: Unknown 13 2 2 1907 2005

Opponents There are a whole host of different suggestions as to who the opponents in Jude are. However, some options appeared only in a single study: Paul (1869), Marcus Followers (1905), General (1962), Political Agitators (1964), Judaizers (1978), Immoral (2006), Judean Zealots (2015). Two studies (1968, 1976) suggested Essenes.

Since Chaine (1939) suggested Paulinists, Bauckham (1983) has promoted the idea, with Sellin (1986) following, while Holloway (1996) and Horrell (1998) changed this to Radical Paulinists. Another strong trend has been Gnostics, with Harnack (1897) first suggesting this, but with twenty- one of our studies following his lead, if we include the suggestion of Marcus Followers, who were a particular group of Gnostics. Notably, thirteen of these studies were in German, and one in French, ending in 1994. The seven English studies all ranged between 1962 and 1984. Eighteen other studies have suggested protognostics, using terminology such as ‘incipient Gnosticism’, ‘embryonic Gnosticism’ or the ‘germs’ of Gnosticism. This last term belongs to Farrar (1882), but most of these studies have been much later, with all but three written from the 1960s onwards, ending in 1992. Four of these studies are in German, and three in French. The last English studies suggesting protognostics were both published in 1980.

Labels overlap, with many of those suggesting Gnostics or protognostics, using additional labels, such as antinomian, libertine or licentious. Antinomian was suggested in twelve studies, ten of which also suggested Gnostic or protognostic. Huther (1877) first suggested this, though it was last found in two studies in 1986. The four English studies suggesting antinomian were published between Beker (1962) and Bauckham (1983). Libertine was suggested in twenty-two studies, seven of which were German, and was mainly combined with other options. Licentious was suggested in seven studies, always combined with another option: Gnostic, protognostic or Christian false teachers. It was first found in Huther (1877) and last found in Schreiner (2003). Curiously, the three English studies all postdate the German and French studies, beginning with Hiebert (1989).

Hofmann (1875), writing in German, claimed that the opponents were not teachers, perhaps responding to Huther, whose fourth edition (1877), was the first study found that suggested the opponents were Christian false teachers. No other German studies were found to have followed Huther. Salmon (1886) and Chase (1899), writing in English, were the only other studies that claimed the opponents were not teachers. Bigg (1901) wrote the first study found in English to claim they were Christian false teachers, with six of the ten studies found to claim the opponents were Christian false teachers published between 1989 and 2006, five of which are from an evangelical perspective. Notably, the Catholic Study Bible (2011) claims the opponents are not teachers. Reforme Opponents Count Evangelicals d First Last A: Antinomian 12 1 1 1883 1986 CFT: Christian False Teachers 10 6 1 1877 2006 Ess: Essenes 2 0 0 1968 1976 G: Gnostics 21 0 1 1897 1994 Gen: General 1 0 0 1962 1962 Imm: Immoral 1 1 0 2006 2006 Jud: Judaizers 1 1 0 1978 1978 JZ: Judean Zealots 1 1 0 2015 2015 Lib: Libertine 22 4 1 1886 2003 Lic: Licentious 7 3 0 1883 2003 MF: Marcus Followers 1 0 0 1905 1905 NT: Not Teachers 3 0 0 1875 1899 Pa: Paulinists 3 1 0 1939 1986 Paul: Paul 1 0 0 1869 1869 PolAg: Political Agitators 1 0 0 1964 1964 PG: Protognostics 18 2 1 1882 1992 RPa: Radical Paulinists 2 0 0 1996 1998

Insiders? Salmon (1886) wrote that the opponents were insiders, followed by seven other studies, the last of which was published in 2008. Wand (1934) wrote that they were outsiders, followed by twelve studies, the last of which was published in 2012. Bauckham (1983) was the first of the four evangelicals found to have suggested the opponents were outsiders. Two evangelicals (1990, 2008) suggested they were insiders.

Evangelical Reforme La Insiders? Count s d First st 2 0 0 In: Insiders 8 2 0 1886 8 2 0 1 Out: Outsiders 11 4 0 1934 2

Dependency Three studies, all by evangelicals and dated between 1968 and 1992, claimed that it was irrelevant whether 2 Peter or Jude was written first. Seven studies were found to claim that Jude was written first. These were all written in English, and published between 1963 and 1993, with the exception of Mayor (1907) and Bateman (2015). Fronmuller (1867) had earlier written in German that 2 Peter was written first. Six other studies followed this lead, all in English and spread out between 1884 and 1989.

Reforme Which came first? Count Evangelicals d First Last I: Irrelevant, copying unlikely 3 3 1 1968 1992 J: Jude 7 3 0 1907 2015 P: 2 Peter 7 1 0 1867 1989

Bateman

The latest commentary in this analysis is by Bateman, in the Evangelical Exegetical Commentary series. It was published in 2015 and is possibly the longest commentary on Jude ever written. Therefore, it is interesting that Bateman takes a very different line than any other studies considered here by arguing that Jude’s opponents are zealots, rather than Christian false teachers, protognostics or antinomians, for example. It is interesting to see how little this reading depends on new translations or interpretations of individual verses. In verse 19, his translation of ἀποδιορίζοντες ‘making-divisions/causing-divisions/separating’ is ‘cause divisions’, which is the most common translation in both studies and Bibles. It is only his interpretation of the way that divisions are caused (i.e. by zealots) that differs.

Only time will tell if his unusual translations, such as ‘deliverance’ instead of ‘salvation’ in verse 3 and ‘protect from harm’ rather than ‘keep from stumbling/falling’, and his unusual interpretations, such as understanding sexual immorality to be ‘extramarital sex’ rather than ‘sex with angels’ or ‘homosexuality’ in verse 7, will stand the test of time.

First Bi First Last Bibl Last Stances Stud b Ev R Study Study e Bible 19.02 CC: Classify the Community 15 0 1 0 1907 2000 19.02 CD: Cause Divisions (Elitists/Wealthy/Zealots) 19 10 8 1 1839 2015 1970 2016 19.02 CD: Cause Divisions (Elitists) 9 0 5 0 1945 2008 19.02 CD: Cause Divisions (Wealthy) 3 0 0 0 1901 1964 19.02 CD: Cause Divisions (Zealots) 1 0 1 0 2015 2015 19.02 S: Separate from others 2 1 1 0 1861 1984 1611 1611 19.02 T: Turn people against each other 0 1 0 0 1995 1995

Stu First Last First Last Stances d Bib Ev R Study Study Bible Bible 3.05 D: Deliver ance 1 0 1 0 2015 2015 3.05 S: Salvati on 11 9 7 0 1951 2006 1901 2016

7.06 A: sex with Angels 14 0 3 0 1934 2008 7.06 E: Extram arital sex 1 0 1 0 2015 2015 7.06 H: Homos exualit y 8 0 4 0 1965 2006 Individual Verses

A quick glance at the data is enough to demonstrate that some stances have been adopted by only one study, and no later studies have been found to follow them. For example: in verse 3, Huther (1877) was the only study suggesting that the participle παρακαλῶν ‘exhorting’ indicated the type of writing, as opposed to the purpose (‘to write appealing to you ‘ – ESV) or an addition to writing (‘write and urge’ – NIV); in verse 5, Bigg (1901) stood alone in suggesting that Jude is providing new information, rather than a reminder; also in verse 5, τὸ δεύτερον ‘the second time’ (‘afterward – ESV; ‘later’ – NIV) is thought to refer to the Babylonian captivity by Fronmuller, and the Roman invasion by Zahn (1909) and Wohlenberg (1923), but to the time in the Wilderness by all other studies; only Kistemaker (1987) insists that those who deserted their dwelling does not refer to the angels in Genesis 6:1-4; and τὸν ὅμοιον τρόπον τούτοις ‘the similar manner to these’ is connected with the preceding ‘the cities around them’ only in the KJV (1611), rather than the following participles ‘having committed... and having gone out’.

However, the fading in popularity of certain stances is better portrayed through graphs. For example, in verse 3, three options for the participle ποιούμενος ‘doing’ are suggested. No studies, but three Bibles, suggest it is contrastive (‘I was doing... but’). This is weakly supported compared to the other two suggestions. Twelve studies and six Bibles suggest it is concessional (‘Although I was doing’) and thirteen studies and twelve Bibles suggest it is temporal (‘While I was doing’). At first glance, the latter two options seem fairly evenly matched, but the graphs suggest a different story. Most commentaries now favour the Concessional (‘Although’) over the Temporal (‘While’) and Bibles may be increasingly adopting this approach.

First Last Stud Last First Bibl Stances Stud Bib Ev R y Study Bible e 3.03 A: Althoug h I was doing (Conces sion) 12 6 6 0 1969 2015 1984 2016 3.03 B: I was doing... But... (Contra st) 0 3 0 0 1971 1996 3.03 W: While I was doing (Tempo ral) 13 12 3 0 1839 2008 1536 1989 Also in verse 3, the summary data appears to suggest that ‘eagerness’ has the edge over ‘diligence’ in translating πᾶσαν σπουδὴν 'pasan spoudēn', but the graph suggests it is not that close. ‘Eagerness’ has overtaken ‘diligence’ in both recent studies and Bible translations. The caveat is the number of studies. To check whether this really is the case, it would be helpful to have more Bibles, and probably studies, included in the survey. The more studies and Bibles included, the more the informative data is likely to be.

Note that the latest two studies translating ‘diligence’ are deSilva (2012) and Reese (2007). Reese appears to be conservative in her translation. She is also one of the two post-2000 studies still choosing the temporal option above.

First Stu Stud Last First Last Stances d Bib Ev R y Study Bible Bible 3.04 D: Diligence 9 4 3 0 1907 2012 1611 1995 3.04 E: Eagerness 18 5 11 0 1939 2015 1984 2016 A Warning

Sometimes the summary data shown is not enough to show what is going on. For example, although the summary data shows that the stance that the author ‘stopped writing about salvation’ can be seen as recently as 1993 (Neyrey) in studies and 1992 (TEV) in Bibles, the dates of the other studies are 1861, 1901 and 1907. This may suggest that the TEV has changed the meaning of the text slightly in trying to simplify the language and that Neyrey has revived an old idea, though no-one has followed.

However, care needs to be taken in using the data. Aggregated data generally loses some of the subtlety. Perhaps Neyrey’s “while making haste to correspond with you” and the TEV’s “I was doing my best to write to you...when” are not so different from the NRSV’s “while eagerly preparing to write to you”. There appears to be a difference in the NIV’s “although I was very eager to write to you”, but this is because it opts for stance 1 under 3.03 above (concession). It is not classified under issue 3.02.

Last Bi E First Stud First Last Stances Stud b v R Study y Bible Bible 3.02 D: Did not write about salvatio n 7 9 4 0 1867 1992 1970 1998 3.02 S: Stopped writing about salvatio n 4 1 0 0 1861 1993 1992 1992