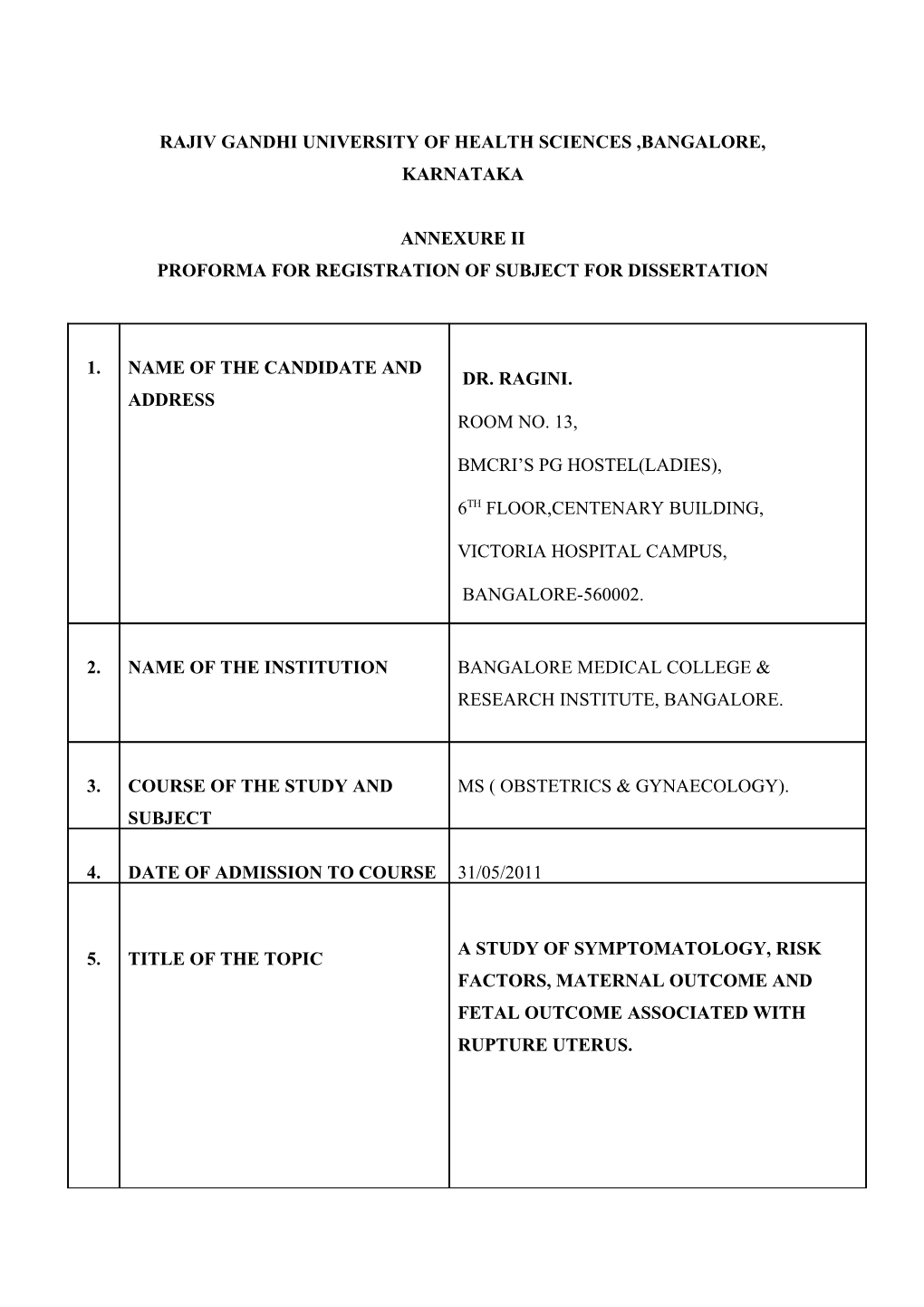

RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCES ,BANGALORE, KARNATAKA

ANNEXURE II PROFORMA FOR REGISTRATION OF SUBJECT FOR DISSERTATION

1. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE AND DR. RAGINI. ADDRESS ROOM NO. 13,

BMCRI’S PG HOSTEL(LADIES),

6TH FLOOR,CENTENARY BUILDING,

VICTORIA HOSPITAL CAMPUS,

BANGALORE-560002.

2. NAME OF THE INSTITUTION BANGALORE MEDICAL COLLEGE & RESEARCH INSTITUTE, BANGALORE.

3. COURSE OF THE STUDY AND MS ( OBSTETRICS & GYNAECOLOGY). SUBJECT

4. DATE OF ADMISSION TO COURSE 31/05/2011

A STUDY OF SYMPTOMATOLOGY, RISK 5. TITLE OF THE TOPIC FACTORS, MATERNAL OUTCOME AND FETAL OUTCOME ASSOCIATED WITH RUPTURE UTERUS.

6. BRIEF RESUME OF THE INTENDED WORK 6.1. Need for the study: Uterine rupture is a potentially catastrophic event associated with high maternal and perinatal mortality. Survivors are often encumbered with morbidities such as obstetric fistulae, psychological trauma, severe anemia and septicemia, which make the recovery process a prolonged and turbulent one. Even after recovery, the impaired reproductive functions that result from surgical management predisposes patients to marital disharmony.1The occurrence of uterine rupture varies in different parts of the world. Its incidence is very low in developed nations, but continues to remain high in developing countries. The rising cesarean section rate leads to an increase in no. of women exposed to the risk of ruptured uterus.2 Uterine rupture stands as a single obstetric accident that exposes the flaws and inequities of health systems and the society at large due to the degree of negligence that it entails. Despite the increasing public concern and support, the most vulnerable: the poor illiterate women from rural communities and their babies hardly get the needed attention3. This study aims at identification of the risk factors (social/economic, logistic, health service, delivery system etc.) so that effective measures can be implemented and the policy makers may be appraised so that effective policy can be mad to prevent this obstetric catastrophe.

6.2. Review of literature: Dissolution in the continuity of the uterine wall any time beyond 28weeks of pregnancy is called rupture uterus. In 2005, an estimated 536,000 women died from causes related to childbirth in the world and 95% were from Africa and Asia. India similar to many sub-Saharan countries is still burdened with a maternal mortality ratio between 214 and 820 per 100 000 live births4 mostly from preventable causes. In a complete rupture there is full-thickness separation of the uterine wall with the expulsion of the fetus and/or placenta into the abdominal cavity where- as the overlying serosa or peritoneum is spared in an incomplete rupture.4 C.O. Fofie et al., in their study showed the major complications of uterine rupture were neonatal/perinatal deaths, maternal mortality, wound infections and total hysterectomy.1 Eze J N et al., in their study showed, a total of 51 ruptured uteri out of 4361 deliveries, yielding a ratio of 1 in 86. A total of 19 (37.3 %) patients had a scarred uterus, while 32 (62.7%) had an intact uterus; yielding a scarred to unscarred uterus ratio of 1 in 1.7.2 Rupture of an unscarred uterus may be spontaneous or traumatic. Spontaneous rupture is rare and most often associated with grand multiparity and long, obstructed labour, whereas traumatic rupture is often secondary to mechanical intervention, such as forceps delivery.4

Begum A,in their study of 32 cases quoted that ruptured uterus was mostly due to cephalopelvic disproportion.5 Cahill and colleagues (2008) found that as the infusion dose of oxytocin increased, so did the risk of uterine rupture. At their maximum infusion dose of 21 to 30 mU/min, the risk of uterine rupture was fourfold greater than that in women not given oxytocin.4 Trial of labour on scarred uterus and the use of uterotonics during labour are the most frequent causes in the developed world while neglected and obstructed Labour 2 stand as the principal factors in developing countries. In some women, the appearance of uterine rupture is identical to that of placental abruption. The condition usually becomes evident because of signs of fetal distress and occasionally because of maternal hypovolemia from concealed hemorrhage as pain tenderness get masked due to analgesics.4 Signs and symptoms include bleeding,abdominal pain palpable fetal parts outside the uterus a fetal head which retract back into abdomen.6 Lower uterine segment dehiscence is the commonest finding. It has been suggested that rupture of an unscarred uterus tends to occur longitudinally.3 Posterior rupture of the uterus is uncommon but can occur with previous uterine surgery or intrauterine manipulation misuse of oxytocics and prostaglandins.7 Kwee Anneke, Bots L Michiel, et al. in their study out of 98 uterine rupture registered, the fetuses was extruded in the abdominal cavity completely in 18 cases and partially in 13 cases.8 With rupture and expulsion of the fetus into the peritoneal cavity, the chances for intact fetal survival are dismal, and reported mortality rates range from 50 to 75 percent. Fetal condition depends on the degree to which the placental implantation remains intact. With rupture, the only chance of fetal survival is afforded by immediate delivery, most often by laparotomy. If rupture is followed by immediate total placental separation, then very few intact fetuses will be salvaged.4 A higher incidence of perinatal mortality and morbidity was associated with complete fetal extrusion and that significant neonatal morbidity occurred when more than 18 min elapsed between the onset of prolonged decelerations and delivery.7 In terms of diagnosing uterine rupture, Farmer et al. (1991) noted that bleeding and pain were unlikely findings (occurring in only 3.4 and 7.6% cases, respectively). The most common manifestation of scar separation was a prolonged fetal heart rate deceleration(70.3%).5 Yalda M A et al. a cross-sectional study showed that the overall incidence of ruptured uterus 0.2% with highest incidence in women aged between 31 and 40yrs with parity >6.9 6.3. Aims and Objectives of the study:

1. To assess the relevance of symptoms associated with rupture uterus.

2. To assess the risk factors associated with rupture uterus.

3. To determine the maternal and foetal outcomes in uterine rupture.

7. MATERIALS AND METHOD: 7.1. Source of Data: Pregnant women being admitted for delivery to Vani Vilas Hospital and Bowring & Lady Curzon Hospital affiliated to Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute (BMC & RI), Bangalore.

7.2. Method of collection of data: A. Study Design: A cross sectional study/Observational study. B. Study period: Nov 2011 – May 2013. C. Place of study: Pregnant women being admitted for delivery at Vani Vilas Hospital and Bowring & Lady Curzon Hospital affiliated to Bangalore medical college and research institute (BMC & RI), Bangalore. D. Sample size: 30 pregnant women E. Inclusion Criteria: 1. All pregnant women of >28wk of gestation with suspected diagnosis of rupture. 2. All Cases of uterine rupture confirmed at laparotomy. F. Exclusion Criteria: 1. Suspected cases of uterine rupture found negative at laprotomy. G. Methodology Around 30 patients with uterine rupture will be included in the study. Patients will be taken according to the inclusion exclusion criteria, detailed history including the name, age, address, contact no. and history pertaining to the various risk factors associated with uterine rupture will be noted in the form of a questionnaire. The presenting symptoms, signs, maternal outcome and fetal outcome and any associated complications will be duly noted. H. Statistical Analysis As the data analyzed is the qualitative data, the chi square test is used. Then, the statistical analysis will be carried out using SPSS software, version 17. 7.3. Does the study require any investigations or interventions to be conducted on patients or other humans or animals? Yes. During the course of hospital stay the following tests may have to be done: 1. Complete hemogram 2. Bleeding time and clotting time. 3. Urine routine and microscopy. 4. HIV, HBsAg, VDRL. 5. Blood urea, serum creatinine. 6. LFT. 7.4. Has the ethical clearance been obtained from your institution in case of 7.3? YES. 8. LIST OF REFERENCES:

1. C.O.Foffie, P.Baffoe. A two year review of uterine rupture in a regional hospital. Ghana Med J 2010September; 44(3):98-102. 2. Eze J N, Ibekwe P C. Uterine rupture at a secondary hospital in Afikpo, Southeast Nigeria. Singapore Med J 2010; 51(6):506-511. 3. Fedorkow DM, Nimrod CA, Taylor PJ. Ruptured uterus in pregnancy: a Canadian hospital’s experience. CMAJ 1987 july;137:27-29. 4. Cunningham F G, Leveno K J, Bloom Steven L, Hauth J C, Rouse D J, Spong C Y. Prior Caesarean Section. William’s Obstetrics. #23rd Edition. Mac Graw Hill,USA;2010; p565- 571. 5. Begum A. Rupture Uterus: A Study of 32 cases. Int JGO2000; 70(2):B91. 6. Johanson R. Obstetric Procedures. In: Edmonds D Keith. Dewhurst’s Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for Postgraduates. # Sixth Edition. Oxford,USA: Blackwell science Ltd ; 1999; p334-335. 7. Kwee Anneke, Bots L Michiel, Visser H A Gerard, Bruinse Hein W. Uterine Rupture and its complications in Netherlands: A Prospective Study. European Journal Of Obstetrics And Gynecology And Reproductive Biology 2006 February;128:257-261 8. Yalda m a and munib a. uterine rupture in dohuk,irak. Eastern Mediterranean health J 2009;15(5):1272-1277. 9. Habiba Ummi, Khattak Zaibunnisa, Ali Mansoor. A review of 66 cases of ruptured uterus in a district general hospital. JPMI 2001;16(1):49-54. 10. Kordoglu Mertihan, Kolusari Ali, Yildezhan Recep, Adali Ertan, Guler Sahin Hanim. Delayed diagnosis of an atypical rupture of unscarred uterus due to assisted fundal pressure. Cases Journal 2009 june;2:7966. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-7966.

9. SIGNATURE OF CANDIDATE Dr. Ragini

10. REMARKS OF THE GUIDE The study might throw light on preventable factors of uterine rupture and help to provide better care for obstetric population to avert this unwanted emergency situation for both obstetrician and the patient.

11. NAME AND DESIGNATION Dr. SOMEGOWDA, MD (OBG), DGO 11.1 GUIDE Professor & Unit Chief Department Of OBG (Vani Vilas Hospital) BMCRI, Bangalore-560002.

11.2 SIGNATURE

11.3 CO-GUIDE(IF ANY)

11.4 SIGNATURE

11.5 HEAD OF THE Dr. UMADEVI, MD(OBG), DEPARTMENT Professor & HOD, Department of OBGY(Bowring &Lady Curzon Hospital), BMCRI Bangalore.

11.6 SIGNATURE

12. 12.1 REMARK OF THE CHAIRMAN AND PRINCIPAL

12.2 SIGNATURE