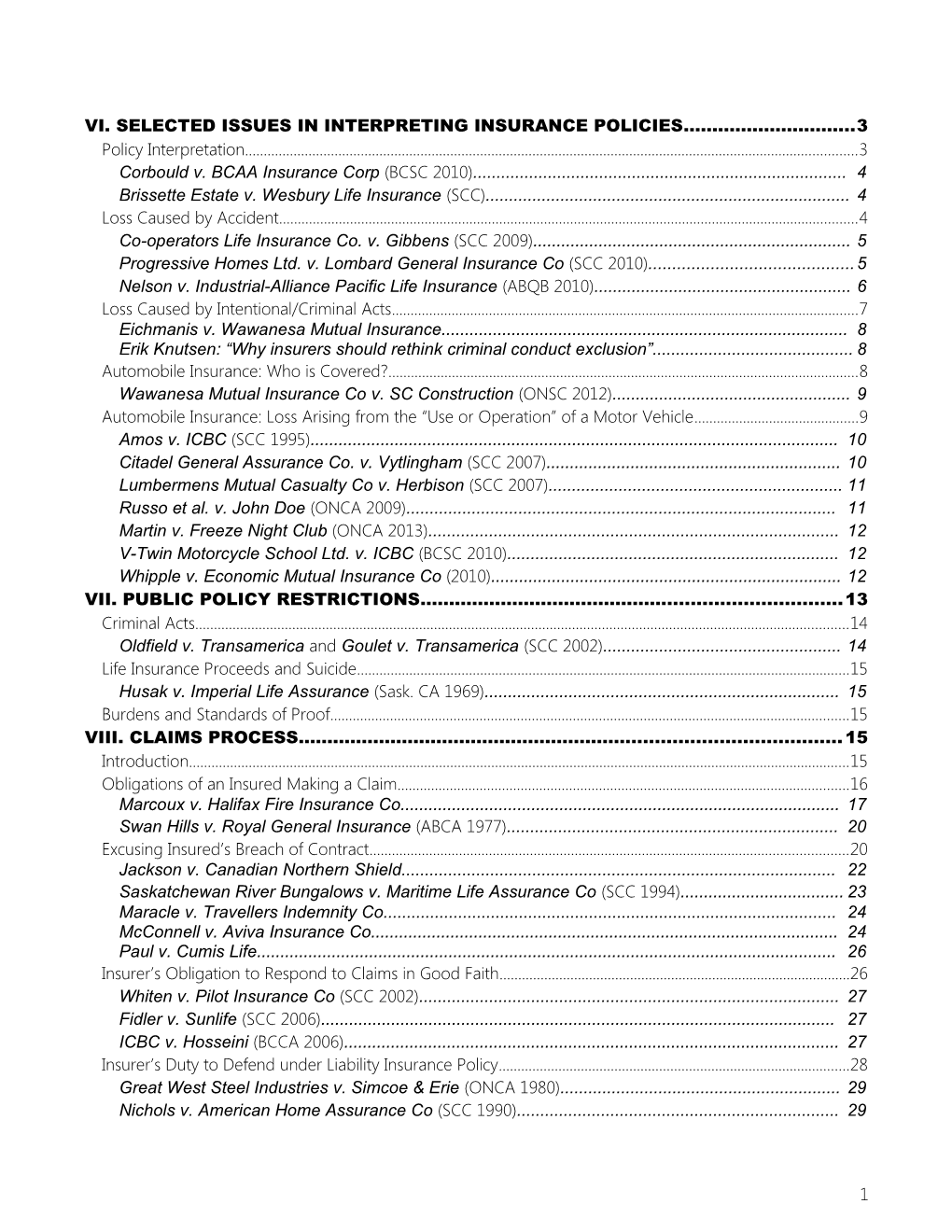

VI. SELECTED ISSUES IN INTERPRETING INSURANCE POLICIES...... 3 Policy Interpretation...... 3 Corbould v. BCAA Insurance Corp (BCSC 2010)...... 4 Brissette Estate v. Wesbury Life Insurance (SCC)...... 4 Loss Caused by Accident...... 4 Co-operators Life Insurance Co. v. Gibbens (SCC 2009)...... 5 Progressive Homes Ltd. v. Lombard General Insurance Co (SCC 2010)...... 5 Nelson v. Industrial-Alliance Pacific Life Insurance (ABQB 2010)...... 6 Loss Caused by Intentional/Criminal Acts...... 7 Eichmanis v. Wawanesa Mutual Insurance...... 8 Erik Knutsen: “Why insurers should rethink criminal conduct exclusion”...... 8 Automobile Insurance: Who is Covered?...... 8 Wawanesa Mutual Insurance Co v. SC Construction (ONSC 2012)...... 9 Automobile Insurance: Loss Arising from the “Use or Operation” of a Motor Vehicle...... 9 Amos v. ICBC (SCC 1995)...... 10 Citadel General Assurance Co. v. Vytlingham (SCC 2007)...... 10 Lumbermens Mutual Casualty Co v. Herbison (SCC 2007)...... 11 Russo et al. v. John Doe (ONCA 2009)...... 11 Martin v. Freeze Night Club (ONCA 2013)...... 12 V-Twin Motorcycle School Ltd. v. ICBC (BCSC 2010)...... 12 Whipple v. Economic Mutual Insurance Co (2010)...... 12 VII. PUBLIC POLICY RESTRICTIONS...... 13 Criminal Acts...... 14 Oldfield v. Transamerica and Goulet v. Transamerica (SCC 2002)...... 14 Life Insurance Proceeds and Suicide...... 15 Husak v. Imperial Life Assurance (Sask. CA 1969)...... 15 Burdens and Standards of Proof...... 15 VIII. CLAIMS PROCESS...... 15 Introduction...... 15 Obligations of an Insured Making a Claim...... 16 Marcoux v. Halifax Fire Insurance Co...... 17 Swan Hills v. Royal General Insurance (ABCA 1977)...... 20 Excusing Insured’s Breach of Contract...... 20 Jackson v. Canadian Northern Shield...... 22 Saskatchewan River Bungalows v. Maritime Life Assurance Co (SCC 1994)...... 23 Maracle v. Travellers Indemnity Co...... 24 McConnell v. Aviva Insurance Co...... 24 Paul v. Cumis Life...... 26 Insurer’s Obligation to Respond to Claims in Good Faith...... 26 Whiten v. Pilot Insurance Co (SCC 2002)...... 27 Fidler v. Sunlife (SCC 2006)...... 27 ICBC v. Hosseini (BCCA 2006)...... 27 Insurer’s Duty to Defend under Liability Insurance Policy...... 28 Great West Steel Industries v. Simcoe & Erie (ONCA 1980)...... 29 Nichols v. American Home Assurance Co (SCC 1990)...... 29

1 Lloyd’s of London v. Scalera (SCC 2000)...... 29 Monenco Ltd. v. Commonwealth Insurance Co. (SCC 2001)...... 30 Summary of the Nichols/Scalera/Monenco Trilogy...... 30 Sommerfield v. Lombard Insurance Group (SCC 2005)...... 32 Hanis v. Teevan (ONCA 2008)...... 32 Broadhurst & Ball v. American Home Assurance Co (ONCA 1990)...... 33 Economical Mutual Insurance Co v. ICBC (ABQB 1986)...... 33 Duty to Settle Within Policy Limits...... 33 X. OVERLAPPING POLICIES AND OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF INDEMNITY...... 34 Doctrine of Contribution...... 34 Determining Insurer’s Liability under Overlapping Policies...... 36 Family Insurance v. Lombard Canada Ltd (SCC 2002)...... 37 Commercial Union Assurance v. Hayden (QB 1977)...... 37 Recovery under Overlapping Policies...... 37 Redefining Policy Coverage in the Event of Other Insurance...... 38 XI. SUBROGATION...... 39 Purposes of subrogation...... 39 Operation of Doctrine of Subrogation...... 39 Castellain v. Preston...... 40 Wellington Insurance Co. v. Armac Diving Services...... 40 Exercising Right of Subrogation...... 40 IX. VALUATION...... 43 Introduction...... 43 Valued Policies...... 44 Re Art Gallery of Toronto and Eaton...... 44 Raymond v. United States Fire Insurance Co...... 44 Unvalued or Open Policies...... 45 Valuation Methods...... 45 Rising Replacement Cost and Inflation...... 46 Dispute Resolution Process...... 48 Future Contingencies...... 49 Leger v. Royal Insurance Co...... 49 Datatech Systems Ltd. v. Commonwealth Insurance Co...... 49 Newfoundland (Attorney General) v. Commercial Union Assurance Co of Canada...... 49 Partial Loss in Valued Policies...... 49 Re Art Gallery of Toronto and Eaton...... 50 Extent of Loss Suffered: Constructive Total Loss, Abandonment and Salvage...... 50 Limits on Liability in Open Policies...... 50 Sue and Labour Clauses...... 51 Benson & Hedges Ltd v. Hartford Fire Insurance...... 52 Office Garages Ltd v Phoenix Insurance Co of Hartford...... 52

2 VI. SELECTED ISSUES IN INTERPRETING INSURANCE POLICIES

Policy Interpretation Insurance contracts are interpreted on a case-by-case basis, with a view to reflecting the intentions of the parties Heavy burden on insurance companies to clearly reflect their intentions in policy wording o Unequal bargaining power between insured and insurer o Limited negotiation with standard form contracts Step one: the search for intention (Consolidated Bathurst Export v. Mutual Boiler) o Search for an interpretation which promotes or advances the true intent . Literal meaning should not be applied where to do so would bring about an unrealistic result . Holistic interpretation to achieve commercially reasonable outcome o Principles: . Undefined words should be given plain and ordinary meaning, but if there are two meanings then go with the one that is more reasonable in promoting the intention of the parties . Contract should be interpreted as a whole, with the presumed purpose of the reasonable protection of the insured . Objective of the contract should not be negated by a technical definition Step two: if there are two reasonable but differing interpretations after step 1 o Contra proferentem . Ambiguous terms are interpreted against the party who drafted the agreement (the insurer) . Does not apply to statutory conditions because they are not drafted by the insurer o Broad interpretation of coverage clauses/narrow interpretation of exclusion clauses . May apply to statutorily mandated provisions that are immune to contra p. o Fulfillment of the reasonable expectations of the parties . American approach is to resolve ambiguities by interpreting the contract in accordance with the insured’s reasonable expectations . Unclear whether this doctrine can apply where the contract terms are not ambiguous . Applies to both expectations of insurer and insured, but giving effect to the expectations of the insured may go against contra proferentem . Blurred distinction between reasonable expectations doctrine and the primary principle of interpreting a contract in accordance with intentions of parties o E.g. Reid Crowther Ltd. v. Simcoe & Erie General Ins Co (SCC 1993)) . Different use of triggering words in different parts of the policy created ambiguity as to whether the policy was limited to claims or occurrences within coverage period Public policy

3 o Courts need to limit the degree to which they allow contextual or public policy considerations to influence their interpretation of insurance contracts . Jesuit Fathers of Upper Canada v. Guardian- public policy considerations do not and should not trump foundational principles of interpretation Double endorsement requirement precluded claims due to circumstances known prior to commencement of coverage period- favoured insurer to insured’s detriment o May be more appropriate for the courts to use statutory authority or draw on estoppel to refuse to apply an unreasonable provision, rather than to interpret it in favour of the insured o Examples of interpretation pp. 149-150

Corbould v. BCAA Insurance Corp (BCSC 2010) Facts: above ground oil storage tank leaked into ground and home, insurer denied coverage because policy excluded loss due to pollution or contamination and that the escape of fuel oil into the property is within the plain and ordinary meaning of contamination/pollution Analysis: a reasonably informed person would consider a spill of 950L of heating oil to constitute contamination or pollution- there is no ambiguity o Parties’ intentions prevail- unnecessary to resort to reasonable expectations absent ambiguity o The only time that we should consider reasonable expectations of the parties as an independent tool absent ambiguity is if not doing so would render the whole contract useless (if the purpose of the contract was threatened)

Brissette Estate v. Wesbury Life Insurance (SCC) Facts: couple had a life insurance policy but it didn’t say who would be the beneficiary if the death was caused by one of them Issue: should insurance proceeds be payable for the benefit of the executor who murdered the insured? Held: no matter how the policy is interpreted, finding in favour of the beneficiary would allow him to recover from the loss that he has caused- public policy was applied o Dissent saw this as an ambiguity because the policy did not provide for what should happen if the beneficiary causes the loss, so should interpret in insured’s favour

Loss Caused by Accident Unless specifically stated otherwise, insurance contracts are interpreted as impliedly excluding coverage for expected losses (and inevitable wear and tear), but many losses are neither purposely caused nor entirely fortuitous Continuum: purely fortuitous, blameless event – negligent act – grossly negligent – reckless act – action intended to cause loss Evolution of definition of “accident” o Walkem: includes negligence of the insured Contract provided coverage for accidents, but the damage was caused by collapsing cranes that were negligently repaired by the insured

4 SCC held that interpreting “accidents” to mean only wholly anticipated events would be unreasonably narrow Even calculated risks can be accidents as long as the outcome was not desired o Stats: plain and ordinary meaning of “accident” includes gross negligence, but excludes recklessness or “a foolhardy venture from which personal injury could be foreseen as an almost inevitable consequence” Insurer said that there should be a narrow construction where the focus of the policy is just to indemnify the specific insured- liberal construction is only applicable to policies that protect third parties Court rejected this- the definition of accident is the same for accident and indemnity policies The fact that the insured was grossly negligent does not mean she desired the outcome o Martin: the question of whether a loss was caused by an accident depends on the insured’s state of mind, not the activity undertaken by the insured Insured’s death due to an overdose is still an accident even if he intended to inject himself, because he did not intend to cause his death Engaging in risky behaviour does not mean that the resulting loss was intentional Insured’s expectations or intentions should be ascertained from his subjective perspective, or from the perspective of a reasonable person in the insured’s position If the insured expected the loss to occur then it is not an accident Note that the finding in Martin is restricted to situations where the insured’s actions led to the loss- ONCA has held that death from natural causes is not an accident

Co-operators Life Insurance Co. v. Gibbens (SCC 2009) Facts: insured had unprotected sex and contracted herpes, which caused a rare complication that resulted in total paralysis of his lower body Issue: does the paraplegia constitute “bodily injury occasioned solely through external, violent and accidental means”? Analysis: “accident” involves something fortuitous and unexpected, as opposed to something proceeding from natural causes- should be given its ordinary meaning o Just because an outcome is unexpected does not establish the existence of an accident within the scope of the policy (Wang) Held: “accident” does not include ailments proceeding from natural causes o The bodily injury proceeded from natural causes in this case, since the transmission followed the normal method by which sexually transmitted diseases replicate o Onus is on the claimant to show that the loss is covered by the policy . Once the claimant establishes a prima facie case that the injury was caused by an accident, the burden shifts to the insurer to show that it was not an accident o Average insured test: “accident” is an ordinary word- should be construed as it would be understood by the average person applying for insurance, not as it might be perceived by persons well versed in insurance law- should be given its plan and ordinary meaning

5 Progressive Homes Ltd. v. Lombard General Insurance Co (SCC 2010) Facts: Progressive homes was hired as a general contractor, negligently built housing complexes, actions were brought against Progressive o Insurance policies required Lombard to defend and indemnify Progressive when Progressive is legally obligated to pay damages because of property damage caused by an occurrence or accident o Lombard argues that interpreting “accident” broadly would effectively make Commercial General Liability policies into guarantees of the quality of the work done by the insured . Court rejects this position- performance bonds ensure that work is brought to completion, whereas CGL policies only cover damage to the insured’s own work once completed Analysis: o An insurer is required to defend a claim where the facts alleged in the pleadings, if proven to be true, would require the insurer to indemnify the insured’s claim . Duty to defend is not dependent on the insured actually being liable o It is generally advisable to interpret the policy in the order of: coverage, exclusions, and then exceptions o Onus is on Progressive to show that the pleadings fall within the initial grant of coverage, which covers property damage caused by an accident . Once this is shown, the onus shifts to Lombard to show that the coverage is precluded by an exclusion clause o “accident” should apply when an event causes property damage neither expected nor intended by the insured- need not be a sudden event and can result from continuous or repeated exposure to conditions . whether defective workmanship is an accident is case specific . property damage is not limited to damage to the property of a third party- can include damage to the building that Progressive constructed Held: for Progressive. Lombard’s duty to defend is triggered.

Nelson v. Industrial-Alliance Pacific Life Insurance (ABQB 2010) Facts: Insured died while swimming- medical experts concluded that he likely had an arrythmia (irregular heartbeat) that was the immediate cause of his death Analysis: was his death an accident? Applied principles from Gibbens o Care must be taken not to convert an accidental benefits policy into a general health, disability, or life insurance policy o Circumstances giving rise to claims on accident benefits polcies: . Antecedent mishaps external to the person of the insured (e.g. car accident, slip and fall, bodily injury or death caused by illness that is a consequence of a mishap or untoward event external to the insured) . Antecedent mishaps internal to the person of the insured (e.g. deliberate acts of ordinary living that lead to an unforeseen or unexpected injury, that is a fortuitous and unexpected result of a bodily malfunction peculiar to the insured

6 . Antecedent mishaps due to miscalculation by the insured (e.g. insured has a mistaken belief about circumstances, fails to perform an action in a timely manner or undertake a necessary check, or simply miscalculates the effects) . Disease or illness of the insured- does not constitute an accident if it arises from processes that occur naturally within the body in the ordinary course of events o Accident occurs where: . A prior unexpected mishap or occurrence external to the insured’s body causes bodily injury or death . A disease or illness attributed to a prior unanticipated mishap or occurrence external to the insured’s body causes bodily injury or death E.g. Kolbuc- West Nile was unforeseen . A prior unanticipated mishap or occurrence due to a deliberate action of the insured results in bodily injury or death due to a bodily malfunction peculiar to the insured . A deliberate action on the part of the insured causes bodily injury or death due to the insured’s miscalculation or mistaken belief about his or her circumstances e.g. Martin- drug overdose o Accident does not occur where disease or illness resulting from natural causes or bodily infirmity in the ordinary course of events causes bodily injury or death . E.g. Gibbens (paralysis due to natural processes within the insured’s body), Wang (amniotic fluid embolism natural with child birth), Nelson (death from swimming not caused by mishap) . If the loss was caused by disease from natural causes, then it is not accidental Held: there was no mishap or trauma that triggered the bodily malfunction- swimming is a natural and common event

Loss Caused by Intentional/Criminal Acts Insurance policies often expressly exclude coverage for losses intentionally caused by the insured o Loss is intentionally caused where the insured takes action with the purpose of causing some loss or harm, even if the insured does not intend the extent of the loss actually incurred (Co- operative Fire & Casualty v. Saindon) . E.g. Emeneau v. Lombard Canada: insured tried to commit suicide in his car, car caught fire, exclusion clause applied to preclude recovery because it was an intentional act . Saindon: got in a fight with neighbour, tried to scare him with the lawnmower, which then fell on the neighbour- loss was intentional because the insured took action with the purpose of causing some harm, even if he did not intend the extent of the loss actually caused o Court should look for evidence of the insured’s subjective intent, failing which the court may apply a subjective-objective analysis based on the circumstances of the loss . Whether a reasonable person in the circumstances would have considered the conduct to result in that kind of outcome; whether a reasonable person would have thought that the resulting damage was something that was substantially certain to result from the conduct in question

7 o Intent to injure presumed for inherently harmful conduct, e.g. sexual wrongdoing: Marine Underwriters, Lloyd’s of London v. Scalera; Sansalone v. Wawanesa Mutual Insurance Common law: complete bar- no recovery o This had adverse consequences for 3rd party victims and co-insureds . Scott v. Wawanesa: parents couldn’t recover from son’s conduct because he was an unnamed insured . Beck Estate v. Johnston: loss was caused by co-insured’s wrongdoing Statutory modification: loss or damage from criminal conduct per se not a bar to indemnity- recovery is subject to policy terms o BCIA s. 5: “Unless a contract otherwise provides, a violation of a criminal or other law in force in British Columbia or elsewhere does not render unenforceable a claim for indemnity under the contract unless the violation is committed by the insured, or by another person with the consent of the insured, with intent to bring about loss or damage, except that in the case of a contract of life insurance this section applies only to insurance payable under the contract in the event the person whose life is insured becomes disabled as a result of bodily injury or disease” . Can recover as long as the conduct was not intended to bring about the harm- recovery permitted even if an action was criminal, so long as the resulting loss was not intended But contract can provide otherwise- common law rule can be included in the contract and will be given effect o Ontario Insurance Act s. 118- similar provision Intent to injure or cause harm required; excludes deliberate conduct causing unintended loss (RDF v. Co-operators General Insurance Co)

Eichmanis v. Wawanesa Mutual Insurance Facts: Eichmanis was shot and injured but was 25% contributorily negligent- brought an action against the insurers of the shooter when the judgment went unsatisfied o Policy excludes coverage for bodily injury or property damage caused by any intentional or criminal act or failure to act by any person insured by the policy or any person at the direction of any person insured Analysis: o S. 118 of the Ontario Insurance Act says that unless the contract provides otherwise, a contravention of any criminal or other law does not by that fact alone render unenforceable a claim for indemnity . But the contract does provide otherwise in this case- exclusion clause excludes coverage for losses resulting from criminal acts o The exclusion applies even without proof of intention to cause the injury or damage, so long as the act or omission that causes the harm is criminal in nature- includes all breaches of the Criminal Code regardless of whether mens rea was required . A conviction is not required, but if there is one it is prima facie proof of the fact Held: exclusion clause triggered, no duty to defend

8 Erik Knutsen: “Why insurers should rethink criminal conduct exclusion” Courts are too literalist and have failed to consider two fundamentals: o Insurers exclude “criminal” behavior from coverage to motivate policyholders to avoid definite, unfortuitous losses o Removing liability insurance for “criminal” behaviour removes a primary source of compensation for accident victims The literalist construction of the exclusion ignores the sole purpose of the “criminal act” fortuity clause- to motivate insureds to control behaviour to avoid a definite, unfortuitous loss o By holding that insurance coverage is ousted on the commission of any criminal act, regardless of the insured’s subjective intent, the court transformed the fortuity clause into something more than it was meant to do o No matter how an insured adjusts her risky behaviour, if the behaviour which cause a loss can somehow be construed as a “crime”, coverage is ousted- but “crimes” can happen by accident, as was the case in Eichmanis. Then the behavioural deterrent effect of the clause is lost. o This interpretation also reads an exclusion clause broadly and against the interests of the insured, which goes against standard insurance contract interpretation principles Solution: interpret the clause to require an insured to have the requisite subjective mental intent to bring about the ensuing unfortuitous loss- then the clause will achieve some mediating effect on fortuity

Automobile Insurance: Who is Covered? BCI(V)A s. 63, Reg 447/83: named insured, members of their household, and persons operating the vehicle with the insured’s consent o No liability where vehicle used without insured’s permission No liability where vehicle operated by unauthorized person, e.g. unlicensed driver or otherwise in breach of coverage condition: Insurance (Vehicle) Act s. 75(b), Reg 447/83, s. 55(3), Schedule 10 s. 3(1),(2),(3),(7) Determining whether the insured permitted unauthorized operation is a question of fact: Ins (V) Reg 447/83 s. 55(3.1), Schedule 10 s. 3(3) . Did the insured have actual or constructive knowledge of unauthorized status? . Whether a reasonable person would have known that the person was unauthorized or operated vehicle in breach of coverage conditions

Wawanesa Mutual Insurance Co v. SC Construction (ONSC 2012) Facts: o Statutory condition 4(1) says that you cannot permit another person to drive the insured automobile unless the other person is authorized by law to drive it o Employee’s vehicle stopped working so his employer let him take a company van- he was involved in a personal injury accident and it turned out he didn’t have a valid license Analysis: o An insured will not be in breach of statutory condition 4(1) if he acts reasonably in all the circumstances

9 . Key question is whether the accused took reasonable care (Sault Ste. Marie) o If an insured who has given someone an unqualified permission to drive his car has no reason to expect that the car will be driven in contravention of policy terms, then he cannot be said to have permitted the contravening use . The word “permit” connotes knowledge, wilful blindness, or at least a failure to take reasonable steps to inform oneself of the relevant facts . The proper test is to determine what the insured knew or ought to have known Held: o When the employee was not hired as a driver and a valid drivers license is not necessary, and there are good reasons to believe that he has a driver’s license, it is not unreasonable to let the employee drive the employer’s vehicle occasionally without first demanding to see the actual license . The employer did not act unreasonably in letting the employee take the van home

Automobile Insurance: Loss Arising from the “Use or Operation” of a Motor Vehicle BCI(V)A s. 7 o (1) Subject to section 2 and compliance with this Act and the regulations, the corporation must administer a plan of universal compulsory vehicle insurance providing coverage under a motor vehicle liability policy required by the Motor Vehicle Act, of at least the amount prescribed, to all persons o (a) whether named in a certificate or not, to whom, or in respect of whom, or to whose dependants, benefits are payable if bodily injury is sustained or death results, o (b) whether named in a certificate or not, to whom or on whose behalf insurance money is payable, if bodily injury to, or the death of another or others, or damage to property, for which he or she is legally liable, results, or o (c) to whom insurance money is payable, if loss or damage to a vehicle results o from one of the perils mentioned in the regulations caused by a vehicle or its use or operation, or any other risk arising out of its use or operation.

Amos v. ICBC (SCC 1995) Facts: o Insurance policy provided death and disability benefits where death or injury was caused by an accident that arises out of the ownership, use or operation of the vehicle o Amos was driving his van to California and was surrounded and attacked by 6 men, was shot in the process and rendered permanently disabled o Insurer denied coverage, saying his injury did not result from the use and operation of the insured vehicle Analysis- “Amos Test”: o First, did the accident result from the ordinary and well-known activities to which automobiles are put? . Driving vehicle off-road is an ordinary and well-known activity (Pender v. Squires) . Pushing motorcycle during a driving lesson is also ordinary and well-known (V-Twin Motorcycle School v. ICBC)

10 . Irrelevant if conduct is illegal or dangerous Vytlingham: SCC rejected insurer’s argument to deny indemnity claim where vehicle was used for a criminal purpose Whipple: insured’s negligence not a factor in determining “accident” for first party statutory benefits . Same test for no-fault benefits and indemnity claims o Second, is there some nexus or causal relationship (not necessarily a direct or proximate causal relationship) between the plaintiff’s injuries and the ownership, use or operation of his vehicle, or is the connection merely incidental or fortuitous? . This causal link should be more strictly defined in the context of a liability insurance policy (Vytlingham, Herbison) than in the context of no-fault automobile insurance benefits (Amos) For no-fault benefits coverage, must be an unbroken chain of causation linking the conduct of the motorist as a motorist to the injuries in respect of which the claim is made (Martin) o Injury need not arise from negligent use of vehicle o Connection between injury and use or operation of car need not be direct (Amos) o Vehicle use must be more than fortuitous But for liability policies/indemnity insurance, the insured vehicle must be more than the site of the loss, but a direct causal connection is not required and the insured vehicle need not be the instrument of the injury- causation element is met where the use or operation of a motor vehicle in some manner contributes or adds to the injury without an intervening act which breaks the chain of causation o Vytligham: tortfeasor not at fault as a motorist o Test is more demanding than for no-fault benefits (Vytlingham) Held: Mr. Amos was entitled to disability benefits because he was driving the van when the assaut occurred and was therefore using the vehicle or its ordinary purpose- the shooting had resulted from the attackers’ attempts to gain entry into the van

Citadel General Assurance Co. v. Vytlingham (SCC 2007) Facts: o Insured suffered permanent injuries when the vehicle in which he was traveling was struck by a boulder dropped from a highway overpass bridge by two people who had brought boulders up to the overpass for that specific purpose, and had used their car to transport the boulders and make a getaway o Insurance policy covered damage caused by an inadequately insured motorist, arising directly or indirectly from the use or operation of an automobile Held: while the purpose element of the Amos test was satisfied, the causation element was not- the loss resulted from the tortfeasors act of throwing boulders off the bridge, which was independent from their use of a motor vehicle to bring boulders to the bridge

11 o They were covered for their no-fault benefits- causation test was satisfied because it was the driving of the vehicle that placed them on the highway . But they could not recover the excess losses under the underinsured motorist policy which is an indemnity policy- for indemnity the injury must have resulted from the use of the vehicle (i.e. vehicle must be used as a weapon), but in this case the dropping of the rock was an independent and separate event and so the chain of causation was broken- tortfeasor was not at fault as a motorist

Lumbermens Mutual Casualty Co v. Herbison (SCC 2007) Facts: a group of friends went hunting, one of them had driven to the hunting area in his truck- thought he saw a dear so he stopped his truck and shot the target, which turned out to be another hunter who was permanently disabled by the shot Held: same reasoning as Vytlingham- the plaintiff’s injuries were caused by the defendant firing a rifle, which was unrelated to the defendant’s use of the insured vehicle to travel to the hunting site o He was no longer acting as a motorist at the time of the shooting

Russo et al. v. John Doe (ONCA 2009) Facts: o Appellant was the victim of a drive-by shooting in which she sustained spine injuries that rendered her paraplegic o Insurer said that the shooting was an intervening independent act Analysis: o This case deals with at-fault insurance coverage, so it is outside the scope of Amos and must follow Lumbermens and Vytlingham instead . The at-fault defendant’s tort must be committed as a motorist o Purpose test: excludes only aberrant uses of a motor vehicle . It is the actual manner in which the car is used that is determinative, not the subjective reasons that the tortfeasor may have for using it- therefore, the fact that a motor vehicle is used for a criminal purpose does not necessarily exclude coverage, provided that it is used as a motor vehicle . Met in this case- the vehicle was used to transport passengers and apparatus from one place to another, which is a well-known and ordinary use of an automobile o Causation test: . But-for test is not enough- there must be an unbroken chain of causation linking the motorist as a motorist to the injuries in respect of which the claim is made . Not satisfied- the shooting was a severable intervening event from the use or operation of the motor vehicle

Martin v. Freeze Night Club (ONCA 2013) Facts: Martin is a part time audio technician, was assaulted while loading his car after finishing work- was driven a few blocks in his own vehicle, further assaulted and then abandoned Analysis: o Purpose test is satisfied

12 o Causation test? . An intervening act may not absolve the insurer of liability for no-fault benefits if it can fairly be considered a normal incident of the risk created by the use or operation of the car . Can it be said that the use or operation of the vehicle was a direct cause of the injuries? o His car was nothing more than the venue where the assaults occurred o It is not enough to show that an automobile was the location of an injury inflicted by tortfeasors, or that the automobile was somehow involved in the incident giving rise to the injury- the use or operation of the automobile must have directly caused the injury o His car was not the dominant vehicle in the assaults- all of the assaults except for the car driving over his foot constituted intervening acts that cannot reasonably be said to be part of the ordinary course of things associated with the use or operation of his vehicle o The involvement of the car was merely ancillary or fortuitous to the injuries inflicted

V-Twin Motorcycle School Ltd. v. ICBC (BCSC 2010) Facts: student fell and was injured while pushing a motorcycle during a motorcycle course Analysis: o Did the accident result from the ordinary and well-known activities to which automobiles are put? . Instructing students in the use of a motorcycle as part of a course in learning to operate the motorcycle is part of the ordinary and well-known use of a motorcycle o Is there some nexus between the third-party claimant’s injury and the use or operation of the vehicle by the insured? . There is an unbroken chain of causation from the use of the motorcycle by V-Twin to instruct its student in pushing a motorcycle to the injury

Whipple v. Economic Mutual Insurance Co (2010) Facts: Whipple attempted to do a headstand against a pole in the centre of a party bus, fractured his neck, resulted in incomplete quadriplegia Analysis: o Purpose test: . In the no-fault benefits scheme, the parties expectations about what is covered is governed by what qualifies as an accident- the negligence of the insured person is not a factor . Whether a particular activity associated with a motor vehicle is or is not itself inherently dangerous is not determinative- the test is whether the activity could reasonably be expected to fall within the use or operation of the vehicle . The headstand was within the ordinary use and operation of the party bus

13 o There are few restrictions on the use of the bus- the activities of the group, including the headstand, were not outside the scope of its use or operation o Causation test: . The headstand, though unusual, flowed naturally from the increasingly creative activities around the pole, which was an integral part of the vehicle . The use of the pole was not incidental to the use and operation of the vehicle- it was a key element and thus meets the dominant feature test

VII. PUBLIC POLICY RESTRICTIONS BCIA s. 35: o (1) Despite section 5, if a contract contains a term or condition excluding coverage for loss or damage to property caused by a criminal or intentional act or omission of an insured or any other person, the exclusion applies only to the claim of a person . (a) whose act or omission caused the loss or damage, . (b) who abetted or colluded in the act or omission, . (c) who (i) consented to the act or omission, and (ii) knew or ought to have known that the act or omission would cause the loss or damage, or . (d) who is in a class prescribed by regulation. o (2) Nothing in subsection (1) allows a person whose property is insured under the contract to recover more than their proportionate interest in the lost or damaged property. o (3) A person whose coverage under a contract would be excluded but for subsection (1) must comply with any requirements prescribed by regulation. o Indemnification for innocent co-insured’s proportionate share in subject property- nature of innocent co-insured’s interest in property irrelevant o Intentional/criminal conduct exclusion limited to persons implicated in wrongdoing or prescribed by regulation o Protects victims of domestic violence o Note: limited to property damage or loss; does not include indemnification for bodily injury or death BC Reg 114/2013 s. 7 o (1) For the purposes of section 35 (1) (d) [recovery by innocent persons] of the Act, all classes of persons other than natural persons are prescribed. o (2) For the purposes of section 35 (3) of the Act, a person described by that provision must co-operate with the insurer in respect of the investigation of the loss, including, without limitation, . (a) by submitting to an examination under oath, if requested by the insurer, and . (b) by producing, for examination at a reasonable time and place designated by the insurer, documents specified by the insurer that relate to the loss. BCI(V)A s. 76(6)

14 o The following do not prejudice the right of a person entitled under subsection (2) to have the insurance money applied toward the person's judgment or settlement, and are not available to the insurer as a defence to an action under subsection (3): . (c) contravention of the Criminal Code or of a law or statute of any province, state or country by the owner, lessee or driver of the vehicle specified in the owner's certificate or policy. Where an insurance contract provides coverage for a particular loss, payment of the insurance proceeds may nonetheless be prohibited by public policy o Courts rely on public policy to nullify the operation of a contract where completion of the contract would violate the social or moral values of society- public policy will always trump contractual terms

Criminal Acts Common law: a criminal should not benefit from his crime (criminal forfeiture principle) o Extends to the criminal’s estate and to anyone claiming through the estate . But some courts have suggested in obiter that this should be reformed because of the inherent unfairness of allowing a named beneficiary to recover, but not the insured’s estate- this distinction seems arbitrary As a matter of law, a criminal’s estate stands in the shoes of the criminal, but a beneficiary under an insurance policy does not Statutory modification: BCIA s. 5 restricts the application of the criminal forfeiture rule to circumstances in which the insured commits a criminal act with the intention of bringing about a loss o Exceptions: . Loss or damage caused by insured or 3rd party with insured’s consent intended to cause loss . Contractual terms can override statutory provision (BCIA s. 5) . Life insurance: criminal forfeiture applies, except to insurance payable under the contract in the event that the person whose life is insured becomes disabled from bodily injury or disease Public policy rules are not constrained by contractual terms o An insurance contract designed to cover illegal activity is unenforceable o Public policy considerations do not impact the legal status of the contract so as to render it void or invalid- they simply render it unenforceable on moral grounds . Particular claim fails and insurer is excused from contractual obligation, but contract remains valid o But the need to resort to public policy can be avoided by a well-drafted contract o Reliance on public policy is necessary where the contract is silent on the issue

Oldfield v. Transamerica and Goulet v. Transamerica (SCC 2002) Oldfield was insured under a life insurance policy naming his wife as the beneficiary, died of a heart attack when a cocaine-filled condom in his stomach unexpectedly ruptured Goulet had life insurance naming his wife as a beneficiary and died when a car bomb he was planting unexpectedly exploded

15 Insurer in both cases argued that payment of insurance proceeds would violate the criminal forfeiture principle SCC held in both cases that public policy did not prohibit payment- the beneficiaries were not participants in the criminal acts in question- payment to them did not benefit the guilty insureds

Life Insurance Proceeds and Suicide At common law, life insurance proceeds are not payable if the insured’s death results from suicide Modification by statute: o Provincial insurance statutes commonly override by making contractual suicide clauses enforceable- this permits insurers to cover suicide (BCIA s. 56(1)) . Payment for death by suicide within a specific period can be excluded, or benefits reduced- implied term to pay after stated period . Reinstatement- relevant period from last reinstatement (BCIA s. 56(2)) o But if a life insurance contract is silent as to suicide, common law applies (Husak) Civil Code of Quebec c. 64, article 2441 o Presumption of validity; life insurance not voided by suicide . The insurer may not refuse payment of the sums insured by reason of the suicide of the insured unless he stipulated an express exclusion of coverage in such a case and, even then, the stipulation is without effect if the suicide occurs after two years of uninterrupted insurance . Any change made to a contract to increase the insurance coverage is, in respect of the additional coverage, subject to the clause of exclusion initially stipulated for a period of two years of uninterrupted insurance beginning on the effective date of the increase o Insurer entitled to exclude payment for suicide as a contractual term o Suicide exclusion provision ineffective after 2 years of contract

Husak v. Imperial Life Assurance (Sask. CA 1969) Husak applied for life insurance policy and received an interim assurance certificate providing him with temporary coverage pending the issuance of the full policy o Interim certificate made no mention of suicide o Policy provided that no coverage would be provided if the insured committed suicide within two years of the policy taking effect o 4 days before the insurer issued the full policy, Husak died from an apparent suicide- this death was not covered by the policy

Burdens and Standards of Proof Party seeking payment has the onus of establishing on a prima facie basis that the loss claimed falls within the terms of the insuring agreement o Insurer may introduce evidence to rebut the claimant’s prima facie case Insurer has the burden of proving that the loss is exempted from coverage, whether by application of a contractual exclusion or by the application of public policy

16 Each party must meet its burden of proof on a balance of probabilities, even where the element to be proven is the commission of a criminal or quasi-criminal offence

VIII. CLAIMS PROCESS

Introduction Steps must be followed before an insured can expect to recover benefits: o Insured must advise the insurer of the loss and the insurance claim being advanced o Insurer must investigate, verify, and otherwise respond to the claim . Involves a determination of the validity of the insurance contract and its application to the loss in question, as well as an assessment of the amount of compensation owed by the insurer given the nature of the loss and the terms of the insurance contract

Obligations of an Insured Making a Claim

Notice of Loss . Insured must first advise the insurance company that a loss has occurred o Insurance policies typically include an express notice provision which requires the insured to report losses within a prescribed time frame- this makes timely notice a condition precedent to the insured’s right of recovery . Insurance company bears the burden of proving on a balance of probabilities that the insured failed to comply with the notice obligation . Courts must determine whether and when the insured’s obligation to report the notice was triggered (Marcoux), and whether the insured reported the loss within the specified time frame from the triggering event o Courts have refused to assign standard definitions to terms such as “promptly”, “immediately”, or “as soon as practicable” . These general notice requirements are interpreted in accordance with the circumstances of each case and the ordinary and reasonable understanding of such a requirement (but relative to each other, immediately is more stringent than promptly, and promptly is more stringent than as soon as possible) o Triggering event is most often the date of the loss, but is dependent on context . BCIA s. 29 Statutory Condition 6 o (1) On the happening of any loss of or damage to insured property, the insured must, if the loss or damage is covered by the contract, in addition to observing the requirements of Statutory Condition 9, . (a) immediately give notice in writing to the insurer . BCIA s. 101 Statutory Condition 5 o (1) The insured or a person insured, or a beneficiary entitled to make a claim, or the agent of any of them, must . (a) give written notice of claim to the insurer (i) by delivery of the notice, or by sending it by registered mail to the head office or chief agency of the insurer in the province, or

17 (ii) by delivery of the notice to an authorized agent of the insurer in the province, . not later than 30 days after the date a claim arises under the contract on account of an accident, sickness or disability . BC Reg 447/83 Schedule 10 Statutory Conditions 5 & 6 o Requires insured to promptly give insurer written notice . Rationale for notification requirement o Avoids prejudice to insurer re investigation and defence . Timely investigation . Determine ground to contest claim . Preserves insurer’s salvage interest . Insurer is obliged to provide insured/beneficiary forms for proof of claim upon requrest or within 60 days of receipt of notice of loss (BCIA s. 27(1)) o Forms provided without prejudice to insurer (27(4)) o Failure to provide forms precludes insurer from setting up limitation defence under s. 23(2) (27(2)) o Insurer may be relieved of obligation to provide forms if loss adjusted to satisfaction of insured/payee within 30 days of notice of loss (27(3)) o BCIA s. 101 (accident & sickness) Statutory Condition 6: insurer to provide forms within 15 days from receipt of notice of loss, insured may submit written statement of proof of loss where insurer fails to furnish forms

Marcoux v. Halifax Fire Insurance Co Insured was required to “promptly” notify the insurer of any accident involving bodily injury o Hit someone with his truck, victim insisted he was okay o Insured did not give notice of the accident until 2 months later when the pedestrian sought damages SCC: the notice obligation must be interpreted in the context of the circumstances surrounding the loss o Objective/subjective test: apply the standard of a reasonable person in the position of the insured . Found that in this case a reasonable person would have concluded that bodily injury had probably been suffered at the time of the accident o The good intentions of the insured are irrelevant in determining whether the duty to report a loss has been triggered- insured’s good faith is irrelevant Consequences of breach: claim forfeited o Contract remains valid o No forfeiture absent prejudice to insurer: Bissett v ICBC- timely notification by 3rd party, insurer was not prejudiced because it was aware of the plaintiff’s claim and had the opportunity to investigate

Proof of Loss

18 A proof of loss clause makes the insured’s obligation to prove a loss a condition precedent for recovery- failure to comply results in forfeiture of the right to recover for the loss in question, but contract itself remains valid sufficient evidence of occurrence and value of loss required within specified time time limit and sufficiency of information contextual Dimana v. Pilot Insurance: burden of proof rests on the insured to establish a right to recover under the terms of the policy- must establish on a BoP that: o a valid insurance policy exists o a loss has occurred o the loss occurred during the time period covered by the policies o the loss falls within the coverage of the policy o the amount of the loss obligations to provide notice of loss and proof of loss are distinct and separate acts designed to serve different purposes- proof of loss may amount to notice, but notice is not proof o notice of loss clauses typically require only written notice, but proof of loss clauses commonly require the insured to verify information via statutory declaration court must determine: o whether the insured provided proof of loss within the required time frame . evaluated as a question of fact given the specific circumstances in the case at bar o whether the information provided by the insured was sufficient to satisfy the proof of loss requirement . based on a standard of reasonableness- insured is required to provide information about the loss in his/her possession or which can reasonably be obtained by the insured, and which might reasonably be expected by the insurer in order to usefully evaluate the insurance claim Nixon v. Queen Insurance: proof of loss clause was not satisfied where the insured, who did not have personal knowledge about all the store inventory destroyed by a fire, failed to make inquiries of his clerk and bookkeeper who could have provided this information Anglo-American Fire Insurance Co. v. Hendry: proof of loss obligation was fulfilled when the insured provided the insurer with copies of the last stock-taking records predating the fire, and copies of invoices for goods purchased since that stock-taking BCIA s. 29 statutory condition 6(b) requires proof of loss verified by statutory declaration: o (i) giving a complete inventory of that property and showing in detail quantities and cost of that property and particulars of the amount of loss claimed, o (ii) stating when and how the loss occurred, and if caused by fire or explosion due to ignition, how the fire or explosion originated, so far as the insured knows or believes, o (iii) stating that the loss did not occur through any wilful act or neglect or the procurement, means or connivance of the insured, o (iv) stating the amount of other insurances and the names of other insurers, o (v) stating the interest of the insured and of all others in that property with particulars of all liens, encumbrances and other charges on that property, o (vi) stating any changes in title, use, occupation, location, possession or exposure of the property since the contract was issued, and

19 o (vii) stating the place where the insured property was at the time of loss BCIA s. 101 Statutory condition 5(1)(b)- insured must: o (b) within 90 days after the date a claim arises under the contract on account of an accident, sickness or disability, furnish to the insurer such proof, as is reasonably possible in the circumstances, of . (i) the happening of the accident or the start of the sickness or disability, . (ii) the loss caused by the accident, sickness or disability, . (iii) the right of the claimant to receive payment, . (iv) the claimant's age, and . (v) if relevant, the beneficiary's age

Duty to Cooperate may include other elements than the obligations to provide notice and proof of loss takes on a particular meaning in the context of liability insurance: o vital that the insurer has the insured’s assistance and cooperation both in conducting a proper defence of the claim and in concluding a settlement on advantageous terms o modern liability policies typically include express provisions prohibiting the insured from assuming liability for any claim brought against the insured by a third party, and imposing a general duty on the insured to cooperate with the insurer in the defence of any action . an insured’s breach of this duty entitles the insurer to refuse to defend or indemnify the insured generally defined as obliging an insured to assist willingly and to the best of his judgment and ability o conduct must be material and substantial in order to constitute a breach o some examples of breach: . failure to respond to letters and other communication by the insurer seeking additional information . insured investigated and settled a claim brought against him without involving the insurance company . insured failed to keep the insurer informed about the status of the lawsuit and various offers made to settle by the third party claimant . insured intentionally failed to attend hearings, provide evidence or assist in obtaining witnesses . insured promoted the action brought against him by a third party claimant . insured lied to the insurer about the circumstances of the accident for the first two or three months following the accident liability insurance o insured not to assume liability in 3rd party action- this prejudices the insurer’s interest o insured must assist insurer in defending 3rd party claim, provide necessary information for settlement Fraud by the Insured under common law, insured’s fraud in advancing a claim entitles the insurer to avoid all obligations under the contract o by committing fraud, the insured forfeits all benefits under the policy

20 o this may be modified by the terms of the contract and has been tempered by statutory provisions . provincial fire and car insurance provisions typically provide that fraud by the insured with respect to a claim forfeits the insured’s right to recover for that claim, even if the amount of the fraudulent claim is small an insured commits fraud in advancing a claim where the insured makes false representations to the insurer either knowingly, recklessly, or without an honest belief in the truth of those representations burden of proving fraud lies on the insurer- heavy burden because of the serious nature of the allegation o higher degree of probability than establishing negligence- higher than BoP, but not as high as beyond reasonable doubt o must provide proof of actual fraud- cannot be assumed from omitted or inaccurate information o where the insured makes a gross misrepresentation/overvaluation, a presumption of fraud arises which can only be rebutted by a finding that the insured was honestly mistaken o insurer must prove that fraud was material- capable of misleading the insurer by affecting the insurer’s management or payment of the claim o inadvertence, omission or mistake not sufficient evidence of fraud consequences of a finding of fraud o common law: claim forfeited and contract voidable by insurer- insurer retains premiums o statutory modification: claim forfeited; contract valid (general, s. 29 statutory condition 7; BCI(V)A s. 75) . insurer may exercise unilateral termination o amount of fraudulent claim irrelevant; irrelevant claim may exceed policy limit o stays on your record and is material information for subsequent insurance applications- failure to disclose previous forfeitures due to fraud would be a breach of the disclosure duty o no relief against forfeiture due to fraud (Swan Hills) . if the breach is imperfect compliance, can grant relief, but not for fraud punitive damages: ICBC v. AkersI (BCSC 2009) o vehicle was not being driven by insured- he was drunk and allowed his unlicensed friend to drive, but pretended that he was the one driving when there was an accident o claim was forfeited and punitive damages were assessed against all of the passengers ($500 each) and also against the insured ($5,000 because he was lying to obtain a financial gain)

Swan Hills v. Royal General Insurance (ABCA 1977) Swan Hills operated a hardware store and lumber business, owned the building which housed the hardware store Royal General insured the building against fire loss to a maximum of $29,000, and against fire loss to the building contents to a maximum of $30,000 In completing proof of loss following a fire, an officer of Swan Hills falsely listed three TV sets, a lumber shed and a metal shed amongst the items damaged in the fire o This was fraud, and was material despite the fact that the amount of the insurance contents claim exceeded coverage limits even without the addition of the fraudulently claimed losses

21 o Court rejected officer’s suggestion that he understood the purpose of the proof of loss to be a negotiating position only o The claim for both building and contents coverage was vitiated despite the fact that the fraud related to the contents only

Excusing Insured’s Breach of Contract BCIA s. 13: o Without limiting section 24 of the Law and Equity Act, if (a) there has been (i) imperfect compliance with a statutory condition as to the proof of loss to be given by the insured or another matter or thing required to be done or omitted by the insured with respect to the loss, and (ii) a consequent forfeiture or avoidance of the insurance in whole or in part, or (b) there has been a termination of the policy by a notice that was not received by the insured because of the insured's absence from the address to which the notice was addressed, and the court considers it inequitable that the insurance should be forfeited or avoided on that ground or terminated, the court, on terms it considers just, may (c) relieve against the forfeiture or avoidance, or (d) if the application for relief is made within 90 days of the date of the mailing of the notice of termination, relieve against the termination. o Note that this section is applicable to accident and sickness insurance (s. 93) Law & Equity Act s. 24- general power to grant relief against forfeiture o The court may relieve against all penalties and forfeitures, and in granting the relief may impose any terms as to costs, expenses, damages, compensations and all other matters that the court thinks fit May not be fair to allow one contracting party to void an agreement by relying on a breach of contract if the breach is of a minor, technical nature or was previously condoned Relief from forfeiture, waiver, and estoppel are typically applied to prevent an insurer from successfully relying on an insured’s breach of contract to deny coverage

Relief Against Forfeiture and Termination Relief against forfeiture is an equitable doctrine which allows the court to excuse the insured’s breach in circumstances where the forfeiture of coverage would be unfair to the insured o Purpose of this doctrine is to prevent the insurer from denying a critical benefit to the insured on the basis of a technical breach which is not substantively prejudicial to the insurer Court must decide on the facts of each case whether it should be granted-must be satisfied of two factors, both of which must be established by the insured: o (1) that the doctrine can by applied as a matter of law . this is a threshold to the second factor- unless the doctrine applies as a matter of law, court cannot apply its discretion to grant relief

22 but this is often applied in reverse: if the court has decided that the facts of the case do not merit the application of relief from forfeiture, there is no need for the court to determine whether the doctrine is available as a matter of law o (2) that the facts of the case merit the application of the doctrine the legal threshold depends on three factors: o (1) the source of the court’s power to grant relief . currently authorized by statute, either by specific power to grant relief from forfeiture or by a general power to grant relief in a provincial justice statute (not restricted to the insurance context) o (2) the type of insurance involved . the specific ameliorative provision should be broadly interpreted (Falk Bros) applies to ordinary contract terms as well as statutory conditions, so it applies to all types of insurance contracts unless the relevant insurance legislation expressly states otherwise it is open to the courts to exercise wide latitude in interpreting statutory provisions in a manner favourable to the insured . the general relief power can apply to an insurance contract which is expressly excluded from the reach of the specific relief power e.g. life insurance contracts are omitted from the specific relief power, but this does not implicitly reflect a legislative intention to prevent relief from forfeiture from applying to life insurance contracts at all . do the powers overlap such that an insurance contract may be subject to both sources of relief? Remains an open question Specific provision is both narrower (more restrictively defines the circumstance giving rise to relief) and broader (authorizes the court to provide relief against the consequences of breach of a statutory condition, whereas the general relief power has traditionally been held not to apply to obligations imposed by statute) o (3) the nature of the insured’s breach . specific relief power is only available where the insured’s breach constitutes imperfect compliance (as opposed to non-compliance) with a statutory condition or contract term and where the imperfect compliance relates to the insured loss . insured’s breach must be accidental and not prejudice the insurer (Pilotte v. Zurich- claim was filed 12 years after accident- even if relief from forfeiture was possible it would be inappropriate to exercise discretion because the delay prejudiced the insurer) . Examples: Specific relief power is available where an insured has failed to provide the insurer with timely notice or proof of loss, but is not available to relieve an insured’s failure to commence litigation on the contract within the prescribed limitation period Specific relief power does not apply to breaches which relate to preconditions for the existence of an insurance contract (e.g. not applicable to the insured’s

23 failure to maintain valid vehicle registration/driver’s license as required by automobile insurance legislation) . If an insured’s breach does not fall within the requirements of the specific relief power, can the general relief power apply? Dominant view is that the general relief power does not apply to a wider range of breaches than the specific power- general power does not apply to a breach which the court characterizes as non-compliance with a condition precedent to the contract Under what circumstances should relief from forfeiture be granted? o Two factors relevant to specific power: . (1) has the insurer been prejudiced by the imperfect compliance? . (2) would it be equitable to hold the insured to strict compliance with the relevant legislation? o Three relevant factors where the general relief power applies: . (1) the conduct of the claimant- was it reasonable in the circumstances? . (2) the gravity of the breaches- was the object of the right of forfeiture essentially to secure the payment of money? . (3) the disparity between the value of the property forfeited and the damage caused by the breach o a court should only grant relief in the circumstances where it would be more fair to relieve the insured from the consequences of its breach than to hold the insured strictly accountable for the breach o insured seeking relief must come to court with clean hands- relief will not be granted where the insured intentionally or maliciously breached an obligation, where the insured’s unreasonable conduct led to the breach, or where the insured liked about the circumstances giving rise to the breach the relief from forfeiture section of provincial insurance legislation extends to matters other than statutory conditions- it can apply to contractual terms as well (National Juice Co v. Dominion Insurance Ltd) judge cannot relieve the contractual limitation period (National Juice) no relief from forfeiture for fraud even absent prejudice to the insurer

Jackson v. Canadian Northern Shield Plaintiffs constructed a barn and greenhouse, installed an auxiliary woodstove in the outbuildings and did not disclose the stove to the insurer insurer denied liability when the building was destroyed by fire- installation of the woodstove is a material change and the insured failed to give notice to the insurer relief from forfeiture requires imperfect compliance with a statutory condition o but can not apply here because this was failure to comply (by giving prompt notice of the installation of the woodstove) rather than imperfect compliance o party seeking relief must show (1) there has been imperfect compliance, (2) this imperfect compliance pertained either to a statutory condition as to the proof of loss or to a thing required to be done by the insured about the loss, (3) a consequent forfeiture or avoidance of the insurance occurred, and (4) it is inequitable that the insurance be forfeited or terminated

24 Waiver and Estoppel- Common Law Waiver under the common law: o Applies to alleviate an insured from its strict contractual obligations where there is, on the part of the insurer, “something said or done whereby the performance or observance of the condition or warranty need not be carried out, made nor proved” o Amounts to a purposeful decision, on the part of the insurer, not to hold the insured to a particular contractual obligation- it is an intentional alteration of a contract term which can occur before or after the contract term is breached

Saskatchewan River Bungalows v. Maritime Life Assurance Co (SCC 1994) Facts: life insurance policy was issued on the life of Mr. Fikowski- insurance premiums were payable by Saskatchewan River Bungalows, but Connie Fikowski was named beneficiary o Premiums were payable annually, contract expressly provided for a 31-day grace period for every premium due date o Policy provided for reinstatement within three years of a lapse, subject to evidence of insurability and the payment of all outstanding premiums plus interest o They were usually late on payments and the policy lapsed twice- the first time, Maritime reinstated it in accordance with the policy terms, but the second time they reinstated it without any evidence of insurability o SRB sent a cheque that was not received, then received a premium due notice that asked for a higher premium than the amount they had already sent, so they sent another cheque for the difference but the main cheque still hadn’t arrived o MLA sent a letter advising Connie, but she didn’t send in any more payment- SRB had closed its hotel for the winter and did not regularly pick up its mail o MLA then sent a notice of policy lapse inviting SRB to apply for reinstatement . When SRB tried to reinstate they were refused because Mr Fikowski was terminally ill- Maritime denied payment upon his death because the policy had lapsed . SRB argued that the policy remained in effect because MLA had, by its conduct, waived the right to timely premium payment Analysis: o Court established the two-part waiver test: in order to find that an insurer has waived its right to strict performance of the contract by the insured, evidence must establish that the insurer had: . (1) A full knowledge of rights; and . (2) an unequivocal and conscious intention to abandon them this may be proven by express words or may be implied by action o the waiver test does not require any reliance by the insured on the insurer’s decision to forego its contractual right . but once waiver is established, the insured’s reliance on the waiver is relevant to the insurer’s ability to retract the waiver- can be retracted if reasonable notice is given to the party in whose favour it operates, but reasonable notice is not required where there is no reliance

25 Held: for Maritime. The policy had lapsed before Mr. Fikowski’s death. o There was a waiver (the letter that said that the policy was technically out of force) but this waiver was retracted when the notice of policy lapse was sent. Since SRB became aware of the waiver and the retraction at the same time, there was no reliance and so Maritime was not required to give any notice of its intention to lapse the policy.

Estoppel under the common law Equitable doctrine which essentially prohibits a party from acting inconsistently with representations it has made, where it would be unfair to do so Prevents an insurer from denying coverage on the basis of an insured’s breach of contract where: o An insurer represents to the insured that the contract term will not be enforced; and o The insured relies on this representation to its detriment Two main types of estoppel: o Promissory estoppel: where the insurer makes a representation (promise) about a future state of affairs o Estoppel by representation: Where the insurer makes a representation of fact to the insured (e.g. advising the insured that coverage is provided for a particular loss, accepting premiums after due date, reinstatement within 2 years of policy lapse without proof of good health and insurability, providing defence absent obligation to do so)

Maracle v. Travellers Indemnity Co Promissory estoppel Building owned by Maracle and insured by Travellers was destroyed by fire- insurer and insured were unable to agree as to the value of the building on the date of the loss Insurer sent a letter to Maracle setting out the terms of a “without prejudice” settlement offer o Maracle did not respond to this offer and issued a statement of claim, but it was not filed within one year of the loss as required by the insurance contract o Maracle argued that the insurer was estopped from relying on the limitation period because it had already admitted liability for the claim Analysis: o In order for promissory estoppel to apply, the party relying on the doctrine must establish that the other party has, by words or conduct, made a promise or assurance which was intended to affect their legal relationship and to be acted on o The use of “without prejudice” is commonly understood to mean that if there is no settlement, the party making the offer is free to assert all its rights, unaffected by anything stated or done in the negotiations Held: Travellers did not represent to the insured that the limitation period would not be enforced

McConnell v. Aviva Insurance Co Estoppel by representation Edith McConnell applied to enforce a judgment she had obtained against the employees of a moving company which was issued under a cargo insurance policy issued by Aviva

26 Aviva responded to the claim by filing a defence on behalf of the moving company and its employees, then advised the two employees of the lawsuit- but one employee was unreachable, and they lost contact with the other after he failed to attend examinations for discovery o Aviva argued that the two employees were not insured persons, McConnell argued that Aviva should be estopped from claiming that the two employees were not insured because Aviva had represented that coverage existed when it defended the individuals Held: the two employees were not insured under the policy, and Aviva was not estopped from raising this defence with regard to the claim against the employee that they had never reached, but full estoppel by representation was applied with regard to the employee that they had successfully contacted o Because the one employee (Mallette) knew of the lawsuit and Aviva’s involvement, it was reasonable to infer that he would have understood that Aviva was taking care of his defence because he was covered by the policy

Waiver and Estoppel: Modification by Statute and Contract BCIA s. 14: o (1) The obligation of an insured to comply with a requirement under a contract is excused to the extent that . (a) the insurer has given notice in writing that the insured's compliance with the requirement is excused in whole or in part, subject to the terms specified in the notice, if any, or . (b) the insurer's conduct reasonably causes the insured to believe that the insured's compliance with the requirement is excused in whole or in part, and the insured acts on that belief to the insured's detriment. o (2) Neither the insurer nor the insured is deemed to have waived any term or condition of a contract by reason only of . (a) the insurer's or insured's participation in a dispute resolution process under section 12, . (b) the delivery and completion of a proof of loss, or . (c) the investigation or adjustment of any claim under the contract. o Note that this provision is applicable to general insurance, life insurance (s. 38) and accident & sickness insurance (s. 93) Waiver requirements: o (1) insurer knowingly abandons rights o (2) unequivocally and consciously communicates to insured; written notice excusing insured’s compliance o (3) unfair for insurer to retract promise of abandonment . insurer entitled to retract waiver without notice, but notice required after reliance o note that statutory modifications require that the waiver is stated in writing and signed by a person authorized for the purpose of the insurer under common aw, a waiver can take any form as long as it demonstrates an insurer’s clear intention to give up the right to enforce an insured’s contractual obligation

27 o but s. 14 of the BCIA says that the waiver must be stated in writing . insurer’s written notice to insured signals intention not to enforce contractual right o written documents relating to the insurer’s investigation and adjustment of the loss are not by themselves sufficient to demonstrate waiver waiver and estoppel are broader than relief from forfeiture o no distinction between imperfect and non-compliance o not limited to post-loss technical or minor breaches- applies to any contractual requirement o substantive legal doctrines- not discretionary o prejudice to insurer is relevant examples of waiver and estoppel p. 220-221 documents used by insurers to pre-empt arguments of waiver and estoppel- provide the insured with written notice of a coverage concern and written confirmation that the insurer is not intending, by its subsequent actions, to forfeit its right to withhold coverage o reservation of rights agreement: . insurer unilaterally and unequivocally informs the insured of the insurer’s intention to preserve its right to deny coverage . insured’s consent is not required o non-waiver agreement: . the insurer and the insured mutually acknowledge and agree to the insurer’s reservation of rights . will not be enforced if the terms or relevance of the agreement were misrepresented by the insurer or otherwise misunderstood by the insured . liability insurance: parties can agree on parameters of defence, indemnification arrangement if no duty to defend and indemnify etc o in order to be effective, such documents must clearly set out the rights which are reserved to the insurer . documents are no longer effective once the insurer has denied coverage

Paul v. Cumis Life insured failed to pay premiums and policy lapsed- insured died, his wife reinstated the policy without telling the insurer that he had died held: o no question of waiver arises- a valid waiver requires complete knowledge of, and a conscious intention to abandon, one’s rights- this was not present here because the insurer was not aware that the insured had already died o no estoppel either- she suffered no loss by reason of relying on what was said by the representative . insurer’s conduct did not deprive claimant from obtaining insurance- no insurable risk or life to be insured at the time of the alleged representation

28 Insurer’s Obligation to Respond to Claims in Good Faith insurance contracts give rise to a fundamental and reciprocal obligation on the part of insurer and insureds to deal with one another in utmost good faith o court recognizes that most people buy insurance in order to alleviate the potential emotional and financial stress associated with an unexpected loss, and thus insurance agreements are understood to be peace of mind contracts In order to meet its obligation of good faith, an insurer must: o Investigate and assess the claim objectively and on proper grounds o Act with reasonable diligence during each step of the claims process to see the claim resolved in a timely way o If no reasonable grounds for denying coverage or payment exists, pay the claim on a timely basis The question of whether the insurer has breached this standard depends on the particular facts of each case- examples p. 229 Insurer’s duty to respond to a claim in good faith is distinct from the insurer’s obligation to pay the insured’s loss o The duty to act promptly and in good faith arises the day the insurer receives the claim, as opposed to being relevant only after the insurer’s obligation to pay the claim arises o Duty of good faith arises fro the existence of the insurance contract itself, regardless of whether the contract provides coverage for the loss claimed Consequences of breach of duty of good faith o Pay claim o Insurer may be liable for punitive damages (Whiten) or aggravated/mental distress damages (Fidler- requires reasonable foreseeability at the time of the contract)

Whiten v. Pilot Insurance Co (SCC 2002) Ms. Whiten’s house was destroyed by fire Pilot made a single payment of $5,000 for living expenses and covered the cost of a rental cottage for a few months, then cut off rental payments without telling the Whitens and refused to pay the fire loss claim because it suspected that the loss was caused by arson- did not explain the reason for the denial to the Whitens Held: Pilot had to pay the full value of the lost property, additional living expenses and $1 million in punitive damages- the obligation of good faith dealing means that Whiten’s peace of mind should have been Pilot’s objective, and her vulnerability ought not to have been aggravated as a negotiating tactic o It is this relationship of reliance and vulnerability that was outrageously exploited by Pilot in this case

Fidler v. Sunlife (SCC 2006) Ms. Fidler suffered an acute kidney infection and continued to suffer from chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia- Sunlife provided her with LTD benefits for 6 years, then terminated benefits with no advance notice having concluded that she was no longer temporarily disabled

29 o Based this decision on video surveillance of Ms. Fidler engaged in a variety of daily activities- did not have any medical evidence to support its conclusion o One week before the trial (after maintaining denial of coverage for five years) the insurer reinstated her benefits and paid all amounts owing under the contract Held: Sunlife was liable for aggravated but not punitive damages- diid not breach duty of good faith o A decision by an insurer to refuse payment should be based on a reasonable interpretation of its obligations under the policy, but this duty of fairness does not require that an insurer necessarily be correct in making a decision to dispute its obligation to pay a claim o Mere denial of a claim that ultimately succeeds is not, in itself, an act of bad faith- the question is whether the denial was the result of the overwhelmingly inadequate handling of the claim, or the introduction of improper considerations into the claims process . Sunlife’s denial was based on real, albeit incorrect, doubt as to the extent of Ms. Fidler’s disability

ICBC v. Hosseini (BCCA 2006) Case arose because of physical injuries suffered by Ian Chan when he was a passenger on a motorcycle operated by Mr. Hosseini which was insured under an owner’s policy issued by ICBC o Hosseini was operating the vehicle without the consent of its owner and without a valid license ICBC negotiated a settlement with Mr. Chan and then advised Hosseini that he was not an insured under the ICBC policy because he was not driving with the owner’s consent- claimed reimbursement from Hosseini for the settlement funds paid to Mr. Chan but didn’t communicate that he was not insured for 6 years Hosseini argued that ICBC breached their duty of good faith to him by unreasonably delaying in advising him about their denial of coverage Held: o Regardless of actual coverage, an insured-insurer relationship for the purposes of good faith conduct was established by ICBC’s conduct toward Mr. Hosseini, so he could properly consider himself an insured of ICBC o Insurer’s duty to respond to a claim in good faith may exist independently from coverage . This duty may arise from the insurer’s conduct towards the party seeking coverage, not only on the basis of the contractual relationship between the insurer and the insured o Obligation of good faith was breached by leading him to believe that he was insured