ADW Draft 2/16/12 AP edits 4/2/12

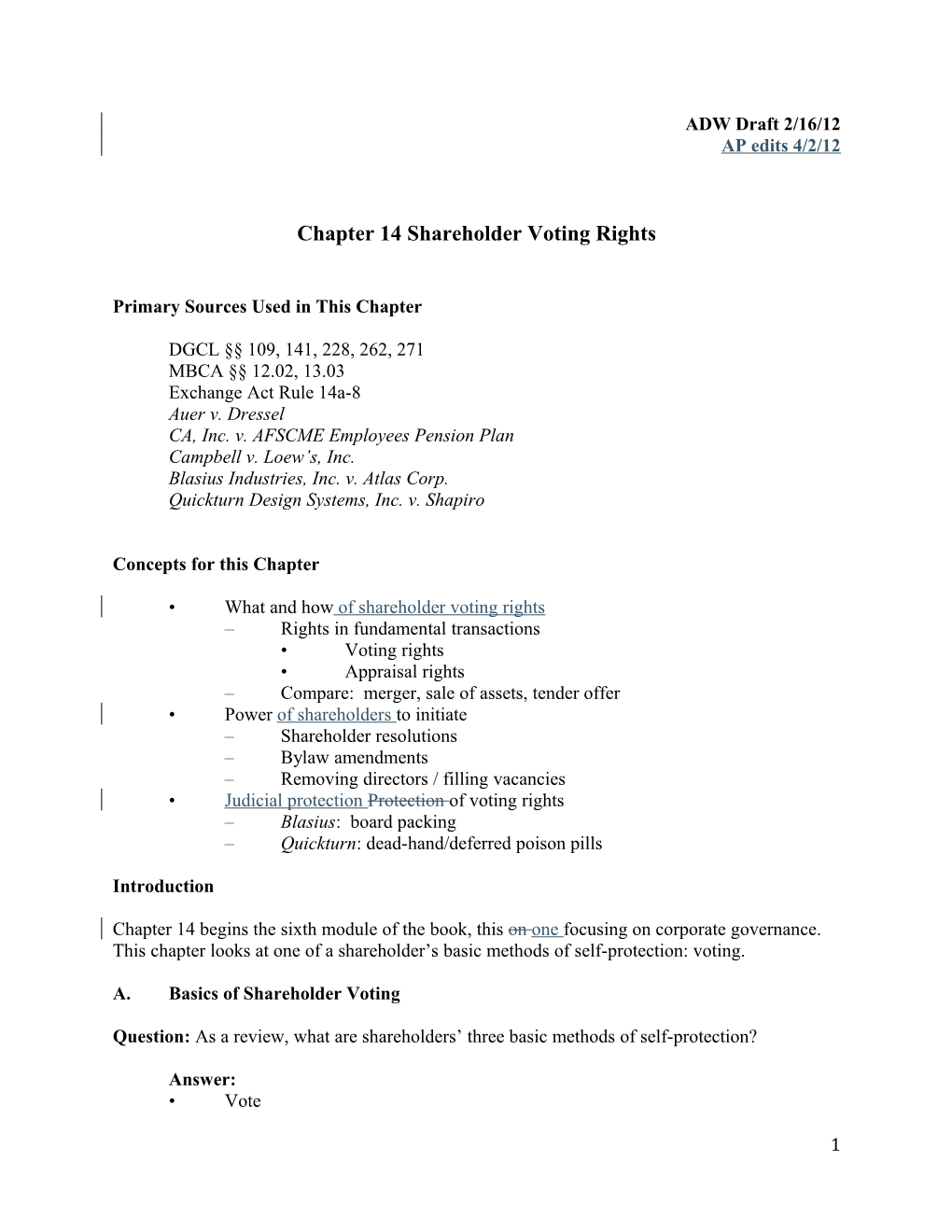

Chapter 14 Shareholder Voting Rights

Primary Sources Used in This Chapter

DGCL §§ 109, 141, 228, 262, 271 MBCA §§ 12.02, 13.03 Exchange Act Rule 14a-8 Auer v. Dressel CA, Inc. v. AFSCME Employees Pension Plan Campbell v. Loew’s, Inc. Blasius Industries, Inc. v. Atlas Corp. Quickturn Design Systems, Inc. v. Shapiro

Concepts for this Chapter

• What and how of shareholder voting rights – Rights in fundamental transactions • Voting rights • Appraisal rights – Compare: merger, sale of assets, tender offer • Power of shareholders to initiate – Shareholder resolutions – Bylaw amendments – Removing directors / filling vacancies • Judicial protection Protection of voting rights – Blasius: board packing – Quickturn: dead-hand/deferred poison pills

Introduction

Chapter 14 begins the sixth module of the book, this on one focusing on corporate governance. This chapter looks at one of a shareholder’s basic methods of self-protection: voting.

A. Basics of Shareholder Voting

Question: As a review, what are shareholders’ three basic methods of self-protection?

Answer: • Vote

1 – Approve fundamental transactions – Elect directors (annually, special meetings) – Remove directors / fill vacancies – Initiate action (amend bylaws, adopt resolutions) • Sue – Enforce fiduciary duties (derivative suits) – Protect rights (disclosure, voting, appraisal, inspection) • Sell – Liquidity (except insider trading) – Takeovers (tender offer)

Although shareholders are often called owners, they have a limited role in corporate governance because of centralized management through the board of directors. The “fundamental transactions” on which shareholders are allowed to vote require initiation by the board of directors, and have to be submitted to a shareholder vote by the board. Even then, such transactions are limited to mergers sales of significant business assets voluntary dissolution, and amendments to the articles of incorporation

1. Shareholder Meetings

Question: When do shareholders have meetings (during which they can act)?

Answer: Shareholders have regularly scheduled annual meetings, and special meetings convened for particular purposes. At a regularly scheduled annual meeting, the only matter required to be addressed is the election of members of the board of directors. Even then, shareholders have a limited ability to remove or replace directors

Question: Can other matters be considered at annual meetings?

Answer: Yes. A board of directors often seeks shareholder approval of other matters such as the ratification of decisions that the board has made during the past year. With the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010, public corporations are also required to hold an advisory (non-binding) shareholder vote approving or disapproving on past management compensation. With the first such “say on pay” vote, each corporation’s shareholders also chose state their preference for how often (1-3 years) to hold such “say on pay” votes.

Question: What happens if a corporation does not hold an annual meeting?

Answer: If there is no annual meeting in the previous 15 months (13 in Delaware), shareholders can bring a judicial action seeking to require an annual meeting.

Question: Can shareholders act in the absence of a meeting?

2 Answer: Yes. They can act by written consent – sending their votes to a “gatherer” who delivers them to the company, instead of voting at a meeting. Some states require such consent to be unanimous. In Delaware a majority (whatever vote would be required if shareholders voted at a meeting) is requiredsufficient .

2. Shareholder Voting Procedures

Question: What sort of notices must be provided to hold a shareholders’ meeting?

Answer: Shareholders are entitled to written notice, at least 10 days (but no more than 60 days) in advance. Notice should include the time and place of the meetings. If it is a special shareholders meeting, notice should also include the purpose of the meeting.

Question: Which shareholders are entitled to vote?

Answer: The board sets a date - the “record date” - before sending out the notice of a meeting. All shareholders on that date (according to the corporation’s records) are entitled to get notice of the meeting and to vote, even if they sell their shares before the meeting. For this reason, pre-meeting purchasers of shares will sometimes ask the seller to cast the shares as instructed (an irrevocable proxy).

Question: How many shareholders have to show up to have a shareholders’ meeting

Answer: Normally a meeting is possible when there is a quorum represented. A quorum is usually equal to a majority of shares entitled to vote on the record date. A corporation can adjust the percentage in its articles of incorporation or bylaws, though usually not below a third.

Question: What is the purpose of a quorum requirement?

Answer: It prevents a minority of the shareholders from calling a meeting and taking some action against the interests of the majority of the shareholders.

Question: Do shareholders have to attend a shareholders’ meeting in person?

Answer: No. They can vote by proxy.

Question: What is a proxy?

Answer: A proxy is a document that the shareholder signs that appoints an agent to vote for him/her/it. It can either specify how the agent should vote the shares, or leave it to the agent’s discretion.

Question: How long does a proxy last?

3 Answer: If it is revocable, until the shareholder submits a notice of revocation, signs a later date proxy or appears in person at a meeting. Whether revocable or irrevocable, proxies are usually limited to 11 months. In closely held corporations, however, irrevocable proxies can be important planning tools and will often last more than 11 months.

3. Shareholder Voting Requirements

Question: How do shareholders vote?

Answer: One share/one vote.

Question: What percentage of shareholders’ votes are needed to approve something at a shareholders’ meeting?

Answer: It depends on the state statute. In some states, shareholders have to approve certain fundamental transactions by a simple majority vote: the number of “yes” votes exceeds the number of “no” votes. In other states (e.g. Delaware) shareholders have to approve certain fundamental transactions by an absolute majority vote: the majority of outstanding shares entitled to vote must vote “yes”.

Example 14.1 on p. 366 illustrates this concept:

ABC Corporation 100 shares outstanding, 60 “represented” at the meeting

Simple majority: 31 Absolute majority: 51

Question: How do shareholders elect directors?

Answer: Normally directors are elected using plurality voting, so the top vote getters for any open directorships are elected. As explained on p. 366, this means that if 5 people are nominated for 5 slots, a single vote will be sufficient to elect each of them. An alternative is to use majority voting in director elections, which would require a director to receive a majority of votes cast to be seated.

Question: Why do directors often get reelected?

Answer: As explained in the Breakout Box at the bottom of p. 366, the shareholder meeting and voting process strongly favors incumbents because they exercise financial control over the voting mechanism. Challengers, also called insurgents, have to use their own money to try to get proxies from shareholders, and only get reimbursed if they win.

Question: Can shareholders remove directors?

4 Answer: Yes. Shareholders can remove directors either for or without cause. The articles of incorporation may restrict the right to removal without cause, but not for cause.

Question: What is a “staggered board” ?

Answer: As explained in the Breakout Box on p. 366, in a corporation with a “staggered board” (also called a “classified board”), directors are elected for multiple-year terms (e.g., 3 years) with some proportion (e.g., one-third) up for election each year.

Question: Who does a staggered board favor?

Answer: The incumbent board, because it would take a challenging (“insurgent”) group multiple years to replace the board.

Question: What is “cumulative voting”?

Answer: As explained in the Breakout Box on p. 366, cumulative voting arrangements let shareholders concentrate their votes for a particular director candidate.

B. Shareholder Rights in Fundamental Transactions

1. Shareholder Voting and Appraisal Rights

Question: What do shareholders get to vote on?

Answer: Shareholders can use their vote to:

Choose directors o annual election o removal / replacement of directors . not easy to remove approve fundamental changes (usually after board initiation) o amendments to articles of incorporation o mergers o sales of all/substantially all assets o corporate dissolution initiate and approve bylaw changes o can be done without board initiation o this is major battlefield in capitalism currently adopt resolutions o advise board on what to do, but are not binding

Question: What do the “fundamental changes” have in common?

Answer: They all involve transactions that change the corporation’s legal form, scope or continuity – but changes to the corporation’s business, even significant ones, do not 5 constitute “fundamental changes.” For example, if IBM decides to stop selling personal computers and focus exclusively on consulting services, the change is not fundamental and does not require a shareholder vote.

Question: What happens when a shareholder disagrees with a fundamental transaction, but is nevertheless outvoted?

Answer: A shareholder can basically “opt out.” A dissenting shareholder can demand that the corporation cash him out at the “fair value” of the shares (as determined by a court in an appraisal proceeding).

In this manner, appraisal provides an “exit right” for dissenting minority shareholders and provides a “floor” on the value of those shares.

States statutes vary with respect to the specific types of transactions that trigger voting and appraisal rights.

2. Shareholder Rights in Corporate Combinations

One area in which voting and appraisal rights often arise is in the case of a corporate combination, or merger. In such a transaction, the business operations of two or more corporations are placed under the control of one management.

a. Statutory Merger

In a statutory merger:

P (the acquiring corporation) and T (the corporation to be acquired) start out as separate legal entities, and end up as a single entity The boards of directors of both corporations adopt a “plan of merger” that specifies The plan of merger is approved by the T, and possibly P, shareholders The plan of merger is filed with the secretary of state and becomes effective The shares of T are converted into the shares of P, which ends up with all of the assets and liabilities of T

The Breakout Box on p. 369 illustrates a statutory merger.

Question: What is included in a plan of merger?

Answer: Specific arrangements such as Which corporation is to survive The terms and conditions of the merger How the shares of T will be converted into shares of P (or other property such as cash or bonds) Any necessary amendments to P articles of incorporation

6 Question: What happens when the plan of merger is submitted to the shareholders, and which shareholders have to approve it?

Answer: The T shareholders almost always vote on a merger, but only get appraisal rights if there is not a public market for their stock (a so-called “market out”). Appraisal rights involve a judicial valuation of the stock.

The exception to T (and P) shareholder voting is when it is a “short-form” merger.

The P shareholders vote if the merger will change the number of shares it has after the merger. P shareholders normally do not vote if it is a “whale-minnow” situation or if there is not a “dilutive share issuance” (i.e. it increases the number of shares by less than 20%). “Dilutive share issuances” are discussed in the Breakout Box on p. 370.

State statutes vary with respect to shareholder approval of a statutory merger. Delaware requires an absolute majority of shareholders of both P and T to approve most statutory mergers.

Question: What is a “short form” merger?

Answer: As explained in the Breakout Box on p. 369, a short form merger is when P already owns at least 90% of T’s stock prior to the voted. In this situation, the T shareholders do not get to vote.

Question: What is meant by “appraisal rights”?

Answer: Appraisal rights refer to the process by which dissenting shareholders can seek fair value for their stock. It is a kind of protection beyond just voting by which shareholders actually go to court, and get a judicial valuation, and then are able to force the corporation to buy their stock.

In a statutory merger, P stockholders do not have appraisal rights, but T shareholders may.

Question: What is the “market out” exception?

Answer: Under the MBCA, T shareholders cannot seek appraisal rights if their stock was publicly traded before the merger and they receive (or retain) cash or marketable stock in the merger.

Under Delaware law, shareholders of both P and T are prevented from seeking appraisal if their stock was publicly traded before and will be publicly traded after the merger.

Of course, both approaches assume that the stock price reflects the value of the stock, which may not be a safe assumption.

7 Question: Which approach provides weaker protection for shareholders – MBCA or Delaware?

Answer: The MBCA, which would deny appraisal rights to acquired company (T) shareholders more often than Delaware law. Under the Delaware law approach, in a stock-for-cash deal, T shareholders would get appraisal rights; Under the MBCA approach, but T shareholders would not.

Question: What if the merger goes through, and a shareholder still does not like it?

Answer: The shareholder may argue that the directors breached their fiduciary duties, perhaps that they had a conflict of interest.

Question: What are some advantages and disadvantages of statutory mergers?

Answer: An advantage of a statutory merger is the fact it makes it easy to transfer assets. A disadvantage is that it exposes P to unknown or contingent liabilities in T’s business. When the statutory merger is complete, P (the surviving corporation) holds the assets and liabilities of both P and T.

b. Triangular Merger

In a triangular merger:

P and T agree to combine P incorporates S: a wholly-owned subsidiary (an acquisition vehicle) P transfers the consideration that is needed for the deal (to pay T’s shareholders) to S P gets 100% of S’s shares in exchange S and T engage in a statutory merger and S acquires all of T’s assets and liabilities

The Breakout Box on p. 372 illustrates a triangular merger. Isn’t the illustration in the breakout box a reverse triangular merger? Yep, it is! I sometimes point out that “deal lawyers” conceive of corporate acquisitions with the same diagrams and boxes as used in the book. Hence, a “reverse triangular merger” is one in which Target is “reversed into” the dummy subsidiary.

Question: What is a “reverse triangular merger”?

Answer: In a reverse triangular merger T is the survivor of the merger with S. Keeping the acquired corporation (T) alive may be helpful for business reasons (e.g., brand name, a contract that might be voidable if T is acquired). T ends up as a subsidiary of P.

Question: What are some advantages and disadvantages of triangular mergers?

Answer: From P’s perspective, an advantage of a triangular merger is that P is not

8 directly exposed to T’s liabilities. From the perspective of P’s shareholders, however, a disadvantage of a triangular merger is the fact that P’s shareholders to not get to vote on the merger. Their shares are not affected by the merger, and P is not a party to the statutory merger (S is). An exception to that under the MBCA is the situation in which P puts more than 20% of its shares into S. In that case, that dilutive effect will trigger a P shareholder voting right.

Similarly, P shareholders do not have appraisal rights in a triangular merger. T shareholders do have appraisal rights, subject to the “market out” exception.

c. Sale of Assets

When a combination is structured as a sale of assets:

P and T agree to sale of assets T shareholders approve (vote on) the sales agreement P buys the assets of T using cash, stock or other securities as consideration

The Breakout Box on p. 374 illustrates a sale of assets.

Question: How do T shareholders’ rights differ in a sale of assets under the MBCA and Delaware law?

Answer: Under the MBCA, T shareholders have appraisal rights, subject to the “market out” exception. Under Delaware law, T shareholders do not have appraisal rights. T shareholders have voting rights with respect to the transaction under both approaches.

Question: What is meant by “sale of assets”? How many assets?

Answer: For purposes of the need for shareholder approval, a sale of assets refers to “all or substantially all” assets of T. Example 14.2 on p. 373 illustrates this principle, as it is set out in DGCL § 271:

§ 271. Sale, lease or exchange of assets; consideration; procedure.

(a) Every corporation may at any meeting of its board of directors or governing body sell, lease or exchange all or substantially all of its property and assets, including its goodwill and its corporate franchises, upon such terms and conditions and for such consideration, which may consist in whole or in part of money or other property, including shares of stock in, and/or other securities of, any other corporation or corporations, as its board of directors or governing body deems expedient and for the best interests of the corporation, when and as authorized by a resolution adopted by the holders of a majority of the outstanding stock of the corporation entitled to vote thereon or, if the corporation is a nonstock corporation, by a majority of the members having the right to vote for the election of the members of the governing body and any other members entitled to vote thereon under the certificate of incorporation or the bylaws of such corporation, at a meeting duly called upon at least 20 days' notice. The notice of the meeting shall state that such a resolution will be considered.

http://delcode.delaware.gov/title8/c001/sc10/index.shtml

9 Do we need to add Gimbel v. Signal Cos., 316 A.2s 599 (Del. Ch. 1974) aff’d per curium 316 A.2d 619 (Del. 1974)? It’s in the breakout box at p. 373. Or do you mean, is this still worth having. I think so. It’s still foundational Delaware law.

Example 14.3 on p. 374 contrasts this with the approach of the MBCA, which requires T shareholders’ approval “if the disposition would leave the corporation without a significant continuing business activity.” MBCA §12.02

MBCA § 12.02. Shareholder Approval of Certain Dispositions.

(a) A sale, lease, exchange, or other disposition of assets, other than a disposition described in section 12.01, requires approval of the corporation's shareholders if the disposition would leave the corporation without a significant continuing business activity. If a corporation retains a business activity that represented at least 25 percent of total assets at the end of the most recently completed fiscal year, and 25 percent of either income from continuing operations before taxes or revenues from continuing operations for that fiscal year, in each case of the corporation and its subsidiaries on a consolidated basis, the corporation will conclusively be deemed to have retained a significant continuing business activity. (b) A disposition that requires approval of the shareholders under subsection (a) shall be initiated by a resolution by the board of directors authorizing the disposition. After adoption of such a resolution, the board of directors shall submit the proposed disposition to the shareholders for their approval. The board of directors shall also transmit to the shareholders a recommendation that the shareholders approve the proposed disposition, unless the board of directors makes a determination that because of conflicts of interest or other special circumstances it should not make such a recommendation, in which case the board of directors shall transmit to the shareholders the basis for that determination. (c) The board of directors may condition its submission of a disposition to the shareholders under subsection (b) on any basis. (d) If a disposition is required to be approved by the shareholders under subsection (a), and if the approval is to be given at a meeting, the corporation shall notify each shareholder, whether or not entitled to vote, of the meeting of shareholders at which the disposition is to be submitted for approval. The notice shall state that the purpose, or one of the purposes, of the meeting is to consider the disposition and shall contain a description of the disposition, including the terms and conditions thereof and the consideration to be received by the corporation. (e) Unless the articles of incorporation or the board of directors acting pursuant to subsection (c) requires a greater vote, or a greater number of votes to be present, the approval of a disposition by the shareholders shall require the approval of the shareholders at a meeting at which a quorum consisting of at least a majority of the votes entitled to be cast on the disposition exists. …

Do we want this text of MBCA 12.02 here? If the question is whether this should go into the ICB, I’m thinking it’s a bit too long. If the question is whether it should be in the TM, my answer is yes.

Question: After the sale of assets, is P responsible for T’s liabilities?

Answer: In a sale of assets, P may but need not assume some or all of T’s liabilities. However, many states employ common law “successor liability” principles to hold P responsible for some of T’s liabilities even if they are not formally transferred.

10 Question: What is the difference between a sale of assets and a statutory merger?

Answer: Sometimes, not a lot, especially when P is assessed successor liability for some of T’s liabilities. If T is dissolved after the sale of assets, the result looks the same as a statutory merger: P owns T’s assets P is owned by its shareholders and former T shareholders

d. Tender Offers

In a tender offer:

P and T do not reach agreement P offers to purchase T shares directly from T shareholders, o P offers cash, P shares or other property o Often P starts in the open market, and then approaches T shareholders when it reaches the 5% ownership point that triggers disclosure o P offers price at premium above market price o P offer usually contingent upon being able to purchase 51% o P offer usually open for a set time T shareholders “approve” by selling their stock to P Once P owns a majority of T shares, P controls T by electing its nominees to the T board of directors

Question: Do T shareholders vote on P takeover by way of a tender offer?

Answer: Technically, no. T shareholders “approve” by selling (“tendering”) their stock to P.

Question: Do T shareholders get appraisal rights?

Answer: No. T shareholders who disagree with the price being offered simply refuse to sell their stock to P at that price.

Question: Do P shareholders get to vote on the combination?

Answer: Probably not, unless P is paying with its own shares that have to be issued, and P: needs to authorize more shares to have enough to issue and/or the issuance of the additional shares would be a dilutive share issuance.

Question: Do P shareholders have appraisal rights in the transaction?

Answer: No.

11 Question: What about T shareholders who do not want the business combined with P?

Answer: They do not sell (though if they constitute a minority of T shareholders, they may be unable to prevent P control.

Question: Why would P use the tender offer method instead of a merger or sale of assets?

Answer: If T’s board of directors will not approve the combination.

Once P has control, it may try to buy out the unwilling T shareholders in a “second-step” transaction like a statutory or a short-form merger. The form used in the second step then determines what rights the minority T shareholders would have.

e. Comparison Chart

The chart on page 376 summarizes P and T shareholder voting and appraisal rights in a transaction in which P acquires T by issuing (as consideration) previously authorized shares constituting more than 20% if its outstanding shares (i.e., a dilutive share issuance).

P (Surviving) T (Acquired) Vote Appraisal Vote Appraisal Statutory Merger MBCA (rev.) Yes No Yes Yes* MBCA (pre-99) Yes Yes Yes Yes DGCL Yes Yes** Yes Yes** Triangular Merger MBCA (rev.) Yes No Yes Yes* MBCA (pre-99) No No Yes Yes DGCL No No Yes Yes** Sale of Assets MBCA (rev.) Yes No Yes Yes* MBCA (pre-99) No No Yes Yes DGCL No No Yes No

* No, if “market exception” applies. The market exception applies if the shares of T are publicly traded before and after the transaction, unless there is a conflict of interest. MBCA§13.02(b)

MBCA § 13.02. Right to Appraisal.

(a) A shareholder is entitled to appraisal rights, and to obtain payment of the fair value of that shareholder's shares, in the event of any of the following corporate actions: (1) approval is required for the merger by section 11.04 and the shareholder is entitled to vote on the merger, except that appraisal rights shall not be available to any shareholder of the corporation with respect to shares of any class or series

12 that remain outstanding after consummation of the merger, or (ii) if the corporation is a subsidiary and the merger is governed by section 11.05; (2) corporation whose shares will be acquired if the shareholder is entitled to vote on the exchange, except that appraisal rights shall not be available to any shareholder of the corporation with respect to any class or series of shares of the corporation that is not exchanged; (3) consummation of a disposition of assets pursuant to section 12.02 if the shareholder is entitled to vote on the disposition; … (b) Notwithstanding subsection (a), the availability of appraisal rights under subsections (a) (1), (2), (3), (4), (6) and (8) shall be limited in accordance with the following provisions: (1) Appraisal rights shall not be available for the holders of shares of any class or series of shares which is: (i) a covered security under Section 18(b)(1)(A) or (B) of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended; or (ii) traded in an organized market and has at least 2,000 shareholders and a market value of at least $20 million (exclusive of the value of such shares held by the corporation's subsidiaries, senior executives, directors and beneficial shareholders owning more than 10 percent of such shares); or (iii) issued by an open end management investment company registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission under the Investment Company Act of 1940 and may be redeemed at the option of the holder at net asset value.

Do we want this text of MBCA 13.02(b) here? In TM, yes.

** No, if “market out” applies. Market out applies if shares of the company are publicly traded before and after the transaction. DGCL §262(b).

DGCL § 262. Appraisal rights.

(a) Any stockholder of a corporation of this State who holds shares of stock on the date of the making of a demand pursuant to subsection (d) of this section with respect to such shares, who continuously holds such shares through the effective date of the merger or consolidation, who has otherwise complied with subsection (d) of this section and who has neither voted in favor of the merger or consolidation nor consented thereto in writing pursuant to § 228 of this title shall be entitled to an appraisal by the Court of Chancery of the fair value of the stockholder's shares of stock under the circumstances described in subsections (b) and (c) of this section. … (b) Appraisal rights shall be available for the shares of any class or series of stock of a constituent corporation in a merger or consolidation to be effected pursuant to § 251 (other than a merger effected pursuant to § 251(g) of this title), § 252, § 254, § 255, § 256, § 257, § 258, § 263 or § 264 of this title: (1) Provided, however, that no appraisal rights under this section shall be available for the shares of any class or series of stock, which stock, or depository receipts in respect thereof, at the record date fixed to determine the stockholders entitled to receive notice of the meeting of stockholders to act upon the agreement of merger or consolidation, were either (i) listed on a national securities exchange or (ii) held of record by more than 2,000 holders; and further provided that no appraisal rights shall be available for any shares of stock of the constituent corporation surviving a merger if the merger did not require for its approval the vote of the stockholders of the surviving corporation as provided in § 251(f) of this title.

13 (2) Notwithstanding paragraph (b)(1) of this section, appraisal rights under this section shall be available for the shares of any class or series of stock of a constituent corporation if the holders thereof are required by the terms of an agreement of merger or consolidation pursuant to §§ 251, 252, 254, 255, 256, 257, 258, 263 and 264 of this title to accept for such stock anything except: a. Shares of stock of the corporation surviving or resulting from such merger or consolidation, or depository receipts in respect thereof; b. thereof, which shares of stock (or depository receipts in respect thereof) or depository receipts at the effective date of the merger or consolidation will be either listed on a national securities exchange or held of record by more than 2,000 holders; c. Cash in lieu of fractional shares or fractional depository receipts described in the foregoing paragraphs (b)(2)a. and b. of this section; or d. Any combination of the shares of stock, depository receipts and cash in lieu of fractional shares or fractional depository receipts described in the foregoing paragraphs (b)(2)a., b. and c. of this section. http://delcode.delaware.gov/title8/c001/sc09/index.shtml

Question: Does the form of a business combination matter?

Answer: Yes. Although the revised MBCA adopts a substance-over-form approach, there is a huge difference in shareholders rights between a statutory merger and a sale of assets under Delaware law.

As discussed in the Breakout Box on pp. 374-5, Delaware courts and those in most other jurisdictions find that the different statutory techniques for combining companies have independent legal significance. So, for example, they reject the idea that some asset sales are “de facto” mergers which would entitle the T shareholders to appraisal rights.

Do we need Hariton v. Arco Electronics, Inc., 188 A.2d 123 (Del. 1963) ? I think it’s still important – and still good law.

C. Shareholder Power to Initiate Action

The board of directors has the power to manage and direct the business affairs of the corporation. Shareholders elect the board, and may vote in other limited instances. The power of shareholders to make recommendations, or advise the board on how it is managing and directing the corporation is limited.

Auer v. Dressel (below) set the ground rules for shareholder recommendations. For public companies, the Securities and Exchange Commission administers specific rules for shareholder proposals. One is Exchange Act Rule 14a-8: Proposals of Security Holders.

Rule 14a-8: Proposals of Security Holders

This section addresses when a company must include a shareholder's proposal in its proxy statement and identify the proposal in its form of proxy when the company holds an annual or special meeting of shareholders. In summary, in order to have your shareholder proposal included on a company's proxy card, and included along with any supporting statement in its proxy statement, you must be eligible and follow certain procedures. Under a few specific circumstances, the company is permitted to exclude your proposal, but only after submitting its

14 reasons to the Commission. We structured this section in a question-and- answer format so that it is easier to understand. The references to "you" are to a shareholder seeking to submit the proposal. a. Question 1: What is a proposal? A shareholder proposal is your recommendation or requirement that the company and/or its board of directors take action, which you intend to present at a meeting of the company's shareholders. Your proposal should state as clearly as possible the course of action that you believe the company should follow. If your proposal is placed on the company's proxy card, the company must also provide in the form of proxy means for shareholders to specify by boxes a choice between approval or disapproval, or abstention. Unless otherwise indicated, the word "proposal" as used in this section refers both to your proposal, and to your corresponding statement in support of your proposal (if any). … g. Question 7: Who has the burden of persuading the Commission or its staff that my proposal can be excluded? Except as otherwise noted, the burden is on the company to demonstrate that it is entitled to exclude a proposal. … i. Question 9: If I have complied with the procedural requirements, on what other bases may a company rely to exclude my proposal? 1. Improper under state law: If the proposal is not a proper subject for action by shareholders under the laws of the jurisdiction of the company's organization; 2. Violation of law: If the proposal would, if implemented, cause the company to violate any state, federal, or foreign law to which it is subject; 3. Violation of proxy rules: If the proposal or supporting statement is contrary to any of the Commission's proxy rules, including Rule 14a-9, which prohibits materially false or misleading statements in proxy soliciting materials; 4. Personal grievance; special interest: If the proposal relates to the redress of a personal claim or grievance against the company or any other person, or if it is designed to result in a benefit to you, or to further a personal interest, which is not shared by the other shareholders at large; 5. Relevance: If the proposal relates to operations which account for less than 5 percent of the company's total assets at the end of its most recent fiscal year, and for less than 5 percent of its net earnings and gross sales for its most recent fiscal year, and is not otherwise significantly related to the company's business; 6. Absence of power/authority: If the company would lack the power or authority to implement the proposal; 7. Management functions: If the proposal deals with a matter relating to the company's ordinary business operations; 8. Relates to election: If the proposal: i. Would disqualify a nominee who is standing for election; ii. Would remove a director from office before his or her term expired; iii. Questions the competence, business judgment, or character of one or more nominees or directors; iv. Seeks to include a specific individual in the company's proxy materials for election to the board of directors; or v. Otherwise could affect the outcome of the upcoming election of directors. 9. Conflicts with company's proposal: If the proposal directly conflicts with one of the company's own proposals to be submitted to shareholders at the same meeting. 10. Substantially implemented: If the company has already substantially implemented the proposal;

15 11. Duplication: If the proposal substantially duplicates another proposal previously submitted to the company by another proponent that will be included in the company's proxy materials for the same meeting; 12. Resubmissions: If the proposal deals with substantially the same subject matter as another proposal or proposals that has or have been previously included in the company's proxy materials within the preceding 5 calendar years, a company may exclude it from its proxy materials for any meeting held within 3 calendar years of the last time it was included if the proposal received: i. Less than 3% of the vote if proposed once within the preceding 5 calendar years; ii. Less than 6% of the vote on its last submission to shareholders if proposed twice previously within the preceding 5 calendar years; or iii. Less than 10% of the vote on its last submission to shareholders if proposed three times or more previously within the preceding 5 calendar years; and 13. Specific amount of dividends: If the proposal relates to specific amounts of cash or stock dividends.

http://taft.law.uc.edu/CCL/34ActRls/rule14a-8.html (notes omitted)

1. Shareholder Recommendations

Auer v. Dressel 306 N.Y. 427, 118 N.E.2d 590(1954)

Facts: Majority shareholders were upset after the company president (Auer) was ousted. The shareholder plaintiffs wanted to compel a special shareholders meeting to (1) hear charges against four Class A directors and remove the directors if the charges were proven, (2) amend the company articles of incorporation and bylaws require that board vacancies could only be filled by shareholders, and (3) endorse Auer as company president. The company bylaws allowed the holders of a majority of the stock to request a special meeting. The company president refused to call the meeting, claiming that the shareholders’ purposes were not proper.

Issue: Were the shareholders’ purposes proper subjects for a Class A shareholder meeting?

Holding: (1) yes, (2) yes, (3) no.

Reasoning: Shareholders could elect and remove directors for cause, and could amend the articles of incorporation and bylaws to dictate the process for the election of directors. Shareholders could not mandate the decisions of the board (e.g. who to elect as president of the company).

Dissent: Judge Van Voorhis argued that none of the cited purposes were proper subjects of a shareholders meeting:

Endorsement of Auer was an “idle gesture;” Letting Class A fill board vacancies was bad for common stockholders; and

16 Removal of directors was more of a judicial function than a shareholder function.

Points for Discussion pp. 379-80

1. Court’s holdings

Question: What power does the court grant shareholders over the board’s selection of a president?

Answer: The court allows shareholders to state their non-binding preference: “there is nothing invalid in their so expressing themselves.”

Question: What is the effect of such an “idle gesture” by shareholders?

Answer: Even a non-binding vote by shareholders has considerable effect on the board. Consider the new “say on pay” rules. How likely is a company to persist with a proposed pay package in the face of shareholder disapproval?

For a more in-depth discussion of say on pay votes in the wake of the Dodd-Frank requirement, and the litigation that has followed, try:

The ongoing debate on The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/corpgov/category/executive-compensation/ [this is a great reference!] or The summary of the SEC’s April 2011 Final Rule on Shareholder Approval of Executive Compensation and Golden Parachute Compensation http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2011/2011-25.htm

2. Power over board composition

Question: Is the power to remove directors explicitly stated?

Answer: No. The court finds that if shareholders have power to elect directors, they have the inherent power to remove them for cause. The court sidesteps the question of which shareholders, since the Class A shareholders are seeking the power to remove and replace the nine (out of eleven) directors elected by the Class A shareholders.

3. Power over articles and bylaws

Question: Who can amend the articles of incorporation and bylaws?

Answer: The Auer v. Dressel court found that the power to amend the bylaws is shared between the board of directors and the shareholders. The court does not confront the process for amending the articles of incorporation, which under New York law must be initiated by the board of directors and then approved by shareholders

2. Bylaw Amendments

17 CA, Inc. v. AFSCME Employees Pension Plan (953 A.2d 227 (Del. 2008)

Facts: AFSCME, a CA, Inc. shareholder, submitted a proposed bylaw for inclusion in the proxy materials of CA. AFSCME’s proposed bylaw would require the corporation to reimburse stockholders for reasonable expenses incurred in supporting board candidates (proxy expenses). CA’s existing bylaws had no specific provision about reimbursing proxy expenses, so the decision was in the discretion of CA’s board of directors, subject to their fiduciary duties and applicable Delaware law.

CA notified the SEC that it was going to exclude the AFSCME language based on their counsel’s opinion that the proposed bylaw was not a proper subject for stockholder action, and if implemented would violate Delaware law. AFSCME, and its counsel, disagreed.

Issues: 1) Is the AFSCME proposal a proper subject of shareholder action? 2) If the AFSCME proposal is adopted, would it cause CA to violate any Delaware law to which it is subject?

Holding: 1) Yes, proper subject, but 2) Yes, might violate law

Reasoning:

1) Proper subject – yes

The bylaw may be proposed and enacted by shareholders without the concurrence of the company’s board of directors. Delaware gives both shareholders and directors power to adopt, amend or repeal the corporation’s bylaws in 8 Del. C. §109(a), but their power is not the same. The Court reads§109(a) with §141(a) (the board manages the business and affairs of the corporation) and decides that bylaws are not meant to mandate how the board makes substantive business decisions, but rather to defined the procedures by which the decisions are made. This proposed bylaw regulates process, and so is a proper subject.

“Implicit in CA's argument is the premise that any bylaw that in any respect might be viewed as limiting or restricting the power of the board of directors automatically falls outside the scope of permissible bylaws. That simply cannot be.”

2) Would the proposals make CA, Inc. violate Delaware law – yes

The court ruled that the proposed bylaw requiring the board to reimburse election expenses of a successful shareholder, because of its mandatory nature, might preclude the board from fully discharging its fiduciary duties. Theoretically, the proposed bylaw might make directors violate fiduciary duties to the corporation by using money for reimbursement of a proxy contest motivated by personal gain, or

18 a proxy contest that promoted interests against the corporation Justice Jacobs found that power of the shareholders to amend the bylaws under §109(a) had to be consistent with the board’s power to manage the corporation under §141(a).

“As presently drafted, the Bylaw would afford CA's directors full discretion to determine what amount of reimbursement is appropriate, because the directors would be obligated to grant only the “reasonable” expenses of a successful short slate. Unfortunately, that does not go far enough, because the Bylaw contains no language or provision that would reserve to CA’s directors their full power to exercise their fiduciary duty to decide whether or not it would be appropriate, in a specific case, to award reimbursement at all.”

Points for Discussion

2. Corporate hierarchy

Question: Which is more powerful, Section 109 or Section 141, of the Delaware law?

DGCL § 109. Bylaws. (a) …After a corporation … has received any payment for any of its stock, the power to adopt, amend or repeal bylaws shall be in the stockholders entitled to vote. … Notwithstanding the foregoing, any corporation may, in its certificate of incorporation, confer the power to adopt, amend or repeal bylaws upon the directors …The fact that such power has been so conferred upon the directors or governing body, as the case may be, shall not divest the stockholders or members of the power, nor limit their power to adopt, amend or repeal bylaws. (b) The bylaws may contain any provision, not inconsistent with law or with the certificate of incorporation, relating to the business of the corporation, the conduct of its affairs, and its rights or powers or the rights or powers of its stockholders, directors, officers or employees. http://delcode.delaware.gov/title8/c001/sc01/index.shtml

DGCL § 141. Board of directors; powers; number, qualifications, terms and quorum; committees; classes of directors; nonstock corporations; reliance upon books; action without meeting; removal. (a) The business and affairs of every corporation organized under this chapter shall be managed by or under the direction of a board of directors, except as may be otherwise provided in this chapter or in its certificate of incorporation. http://delcode.delaware.gov/title8/c001/sc04/

Answer: Section 141, providing the board of directors with the power to manage the affairs and business or the corporation. It is a “cardinal precept.”

5. Proper election-related bylaws

A valid bylaw dealing with election-related expenses might be:

ORIGINAL BYLAW:

19 The board of directors shall cause the corporation to reimburse a stockholder or group of stockholders (together, the “Nominator”) for reasonable expenses (“Expenses”) incurred in connection with nominating one or more candidates in a contested election of directors to the corporation’s board of directors, including, without limitation, printing, mailing, legal, solicitation, travel, advertising and public relations expenses, so long as (a) the election of fewer than 50% of the directors to be elected is contested in the election, (b) one or more candidates nominated by the Nominator are elected to the corporation’s board of directors, (c) stockholders are not permitted to cumulate their votes for directors, and (d) the election occurred, and the Expenses were incurred, after this bylaw’s adoption. The amount paid to a Nominator under this bylaw in respect of a contested election shall not exceed the amount expended by the corporation in connection with such election.

REDRAFTED:

The board of directors [shall cause the corporation to reimburse, unless the board determines that such reimbursement would be harmful to the corporation,] may consider within its discretion whether to cause the corporation to reimburse a stockholder or group of stockholders (together, the “Nominator”) for reasonable expenses (“Expenses”) incurred in connection with nominating one or more candidates in a contested election of directors to the corporation’s board of directors, including, without limitation, printing, mailing, legal, solicitation, travel, advertising and public relations expenses, so long as (a) the election of fewer than 50% of the directors to be elected is contested in the election, (b) one or more candidates nominated by the Nominator are elected to the corporation’s board of directors, (c) stockholders are not permitted to cumulate their votes for directors, and (d) the election occurred, and the Expenses were incurred, after this bylaw’s adoption. The amount paid to a Nominator under this bylaw in respect of a contested election shall not exceed the amount expended by the corporation in connection with such election.

Question: What is a “poison pill”

Answer: As explained in the Example 14.5 on p. 392, a poison pill is a device that forces potential (hostile) acquirers of a corporation to seek permission from the board or suffer significant dilution of their shares. For example, a poison pill provision may allow existing shareholders (but not the acquirer) to buy additional shares at a discount. The provision is intended to make the company less attractive to the acquirers.

3. Removal and Replacement of Directors

DGCL § 141(k). Board of Directors

(k) Any director or the entire board of directors may be removed, with or without cause, by the holders of a majority of the shares then entitled to vote at an election of directors, except as follows: (1) Unless the certificate of incorporation otherwise provides, in the case of a corporation whose board is classified as provided in subsection (d) of this section, stockholders may effect such removal only for cause; or (2) In the case of a corporation having cumulative voting, if less than the entire board is to be removed, no director may be removed without cause if the votes cast against such director's removal would be sufficient to elect such director if

20 then cumulatively voted at an election of the entire board of directors, or, if there be classes of directors, at an election of the class of directors of which such director is a part. http://delcode.delaware.gov/title8/c001/sc04/

Campbell v. Loew’s, Inc. 134 A.2d 852 (Del. Ch. 1957)

Facts: This case involved a battle for control of Loew’s Inc. by two factions, one headed by its President, Vogel, and the other by Tomlinson. At a shareholders meeting in February a compromise was reached according to which each faction would have six directors, and a neutral director would complete the 13-member board. In July four shareholders resigned: two of the Vogel directors, one Tomlinson director, and the neutral director. On July 30, there was a board meeting attended only by the five remaining Tomlinson directors, who attempted to fill two vacancies. The Delaware Chancery Court held that those elections were invalid for lack of a quorum. Meanwhile, on July 29, Vogel sent out a notice for a special shareholders meeting listing the purposes as: 1) to fill director vacancies; 2) to amend the by-laws to increase the number of board members from 13 to 19, and the quorum from 7 to 10, and also to elect six additional directors; and 3) to remove Tomlinson and Stanley Meyer as directors and to fill their vacant positions. The plaintiffs brought suit to enjoin the meeting.

Issues and Holdings:

1) Did Vogel, as President, lack the power to call a special shareholders meeting to amend the bylaws and fill vacancies? . No. The bylaws explicitly granted the president power to call special meetings of stockholders “for any purpose”.

2) Did the stockholders have the power between annual meetings to elect directors to fill newly created directorships? . Yes. Stockholders have an inherent right between annual meetings to fill newly created directorships.

3) Did the shareholders have the power to remove directors from office for cause? . Yes. The court believed the stockholders had the power to remove a director for cause. While the statute did not specifically state this, considering the damage a director could inflict on a corporation, the court believed that the statutes and by-laws had to be construed so as to leave untouched the question of a director removal for cause. So, the Court was free to conclude that the stockholders had such inherent power. . “Thus, I conclude that as a matter of Delaware Corporation law the stockholder do have the power to remove directors for cause.”

4) Did the charges against the directors constitute “cause” as a matter of law?

21 . Maybe. Some of the charges did and some of the charges did not. The president’s letter made various charges stating that the directors were rude, desired to take control, did not cooperate, and had a planned scheme of harassment to the detriment of the corporation. While charges such as the desire to take control, being rude and not cooperating were not legally sufficient to justify the ouster of the two directors, the court held that a “planned scheme of harassment” constituted a justifiable legal basis for removing a director (though the Court expressed no opinion as to the truth of the charges).

5) Were the directors given adequate notice of the charges of grave impropriety, which was a prerequisite necessary to remove a director for cause? . Yes. The proxy statement specifically recited that the two directors “are sought to be removed” for the reasons that were listed in the president’s accompanying letter. Both of the directors received copies of the letter and thus were served with notice of the charges against them.

6) Were the directors afforded an opportunity to be heard, which was a prerequisite necessary to remove a director for cause? . No. If the matter was to be decided by proxy then the directors had to be provided the opportunity to present their defense to the stockholders by a statement, which had to accompany or precede the initial solicitation of proxies seeking authority to vote for the removal of such director for cause. Furthermore, the corporation had a duty to make sure that this opportunity was given to the directors at the corporation’s expense. In this case, no such opportunity was given.

Conclusion: The procedural sequence that was adopted for soliciting proxies that sought to remove the two directors was contrary to law. The result was that the proxies solicited by Vogel had to be declared invalid insofar as they purported to give authority to vote for the removal of the directors for cause.

Points for Discussion

1. What constitutes “cause”?

Note that Campbell was decided before Delaware enacted DGCL §141(k).

Errata: The citation in the paragraph under the heading “What constitutes ‘cause’” on p. 397 should be to “DGCL §141(k),” not “DGCL §142(k)”

Question: Why do shareholders have to have “cause” to remove directors?

Answer: Shareholders cannot interfere with the board’s business discretion. If they could remove directors for any reason, shareholders would be able to interfere with the board’s power.

3. Removal as impeachment?

22 Question: Why are fiduciary duties not enough?

Answer: There are two problems with using violation of fiduciary duties as the only basis for removal. First, there are situations in which fiduciary duty does not exist, yet there is sufficient cause to call for a director’s removal. For example, a director who has been adjudged mentally incompetent, but insists on keeping his board position, could well be subject to removal for cause. Do we have an example? Second, there may be situations in which waiting for the next board election is not feasible and might even itself violate fiduciary duty.

D. Board Responses to Shareholder Initiatives

1. Interference with Shareholder Voting

DGCL § 228. Consent of Stockholders … in Lieu of Meeting

(a) Unless otherwise provided in the certificate of incorporation, any action required by this chapter to be taken at any annual or special meeting of stockholders of a corporation, or any action which may be taken at any annual or special meeting of such stockholders, may be taken without a meeting, without prior notice and without a vote, if a consent or consents in writing, setting forth the action so taken, shall be signed by the holders of outstanding stock having not less than the minimum number of votes that would be necessary to authorize or take such action at a meeting at which all shares entitled to vote thereon were present and voted and shall be delivered to the corporation … (c) Every written consent shall bear the date of signature of each stockholder or member who signs the consent, and no written consent shall be effective to take the corporate action referred to therein unless, within 60 days of the earliest dated consent delivered in the manner required by this section to the corporation, written consents signed by a sufficient number of holders or members to take action are delivered to the corporation… http://delcode.delaware.gov/title8/c001/sc07/index.shtml

Blasius Industries, Inc. v. Atlas Corp. 564 A.2d 651 (Del. Ch. 1988)

Facts: Blasius Industries (P) began accumulating shares of Atlas Corporation (D) and then several months later disclosed that it owned 9.1% of Atlas’ common stock. Blasius also began to urge Atlas to restructure the corporation. At the same time, Blasius announced that it was exploring the feasibility of obtaining control of Atlas. Atlas management did not like the idea of Blasius’ controlling shareholders involving themselves in Atlas’ affairs and did not like the idea of a restructuring.

Blasius then delivered a signed written consent to Atlas: 1) adopting a precatory resolution recommending that the board implement a restructuring proposal, 2) amending the bylaws to expand the size of the board from seven to 15 – the maximum number allowed by Atlas’ articles, and 3) seeking to elect eight persons to fill the new directorship. Blasius also stated that it intended to solicit consents from other Atlas shareholders. Atlas’ CEO and outside counsel viewed this as an attempt to take control of Atlas and called an emergency

23 meeting of the board. The next day the board voted to amend the bylaws to increase the size of the board from seven to nine and then appointed to new directors to fill the newly created positions.

Issue: Did the board, even if acting with subjective good faith, validly act for the principal purpose of preventing the shareholders from electing a majority of new directors.

Holding: No. The board could not act for the principal purpose of preventing the shareholders from electing a majority of new directors even if it was done in good faith.

Rule: A board’s decision to act to prevent the shareholders from creating a majority of new board positions and filling them does not involve the exercise of the corporation’s power over its property, or with respect to its rights or obligations; rather, it involves allocation, between shareholders as a class and the board, of effective power with respect to governance of the corporation. Action that interferes with the effectiveness of a vote inevitably involves a conflict between the board and shareholder majority. Judicial review of such action is necessary and may not be left to the agent’s business judgment rule.

In this case, the issue was not one of intentional wrong, but one of authority as between the fiduciary and the beneficiary. The board was not faced with a coercive action taken by a powerful shareholder against the interest of a distinct shareholder constituency. Rather, it was presented with a consent solicitation by a 9% shareholder. Furthermore, it was given ample time to notify the shareholders about the merits of the proposal. The only justification that could be given was that the board knew better than the shareholders. However, this was irrelevant when the question was who should comprise the board of directors. Corporate law conferred power upon directors as the agents of the shareholders, but it did not create Platonic masters. Thus, even if the action taken was in good faith, it constituted an unintended violation of the duty of loyalty that the board owed to the shareholders. The concept of an unintended breach of the duty of loyalty was unusual but not novel.

Points for Discussion

1. Platonic masters

Question: Do shareholders defer to directors’ authority when they invest in a corporation

Answer: No. Directors do not act “instead of” shareholders, they act “as representatives of” shareholders. They act in the trusted interest of shareholders.

2. Power vs. duty

Question: Why did the court disregard the board’s good faith and pure motivation?

Answer: The question was who had the power to make the decision, not the motivation behind the decision.

24 2. Diminishing the Power of the Board

Quickturn Design Systems, Inc. v. Shapiro 721 A.2d 1281 (Del. 1988)

Facts: Mentor Graphics sought to acquire Quickturn Design Systems. Mentor was in the business of electronic design automation software and hardware and Quickturn was the market leader in emulation technology used to verify the design of silicon chips and electronics systems. Mentor, which had been barred in patent litigation with Quickturn from competing in the United States emulation market, would also realize an extra benefit by acquiring Quickturn. If Mentor owned Quickturn it could “unenforce” the Quickturn patents and enter the U.S. emulation market.

Thus, when Quickturn’s stock price began to decline Mentor initiates a two-step takeover. Tender Offer: It made a cash tender offer for all outstanding shares of Quickturn for $12.125/share (nearly 50% more than the price of the stock at the time, but 20% less than the price was 4 months prior). Proxy Contest: Mentor also disclosed its intent to solicit proxies to replace the board.

Quickturn’s board announced that Mentor’s offer was inadequate and recommended that shareholders reject the offer. Additionally, the Quickturn board adopted two defensive measures. First, the board amended the bylaws, which permitted stockholders holding 10% or more of stock to call a special stockholders meeting.” This in turn, would delay a shareholder special meeting for at least three months. Second, the board amended Quickturn’s shareholder Rights Plan or “poison pill” to add a Deferred Redemption Provision or DRP, which would have the effect of delaying the ability of a newly-elected, Mentor-nominated board to redeem the Rights Plan for six months.

The combined effect of the defensive would therefore delay any acquisition of Quickturn by Mentor for at least nine months. The Court of Chancery determined that the bylaw amendment was valid, but the DRP was invalid on fiduciary grounds. Quickturn appealed the DRP finding.

Issue: Did Quickturn’s directors breached their fiduciary duty by adopting the DRP?

Holding: Yes. The DRP was invalid because it would require newly elected directors to breach their fiduciary duty to the stockholders.

Reasoning: To the extent that a contract, or a provision thereof, purported to require a board to act/not act in a way that limited its exercise of fiduciary duties, the measure was invalid and unenforceable.

The DRP substantially limited the freedom of newly elected directors to make decisions on matters of management policy. It therefore violated the duty of each newly elected director to exercise his own best judgment on matters coming before the board. The DRP would prevent a

25 newly elected board of directors from completely discharging its fundamental management duties to the corporation and its stockholders for six months.

“This Court has held that when confronted by a determined bidder that seeks to acquire a company, no defensive measure can be sustained when it represents a breach of the directors’ fiduciary duty. A fortiori, no defensive measure can be sustained which would require a new board of directors to breach its fiduciary duty.”

Points for Discussion

Question: What is a “dead hand” provision?

Answer: A dead hand provision is an additional defense in a poison pill mechanism that allows the poison pill rights to be redeemed only by “continuing directors” (i.e., directors who were on the board before the adoption of the pill or who were later elected with the recommendation of the other continuing directors). It such a provision works, the challenging (or insurgent) directors cannot get rid of the poison pill mechanism even if they are elected.

Question: What is a “no hand” provision?

Answer: A no hand provision is an additional defense in a poison pill mechanism that does not allow the poison pill rights to be redeemed by anyone for a set period of time after a new board is elected, thereby precluding acquisition of the corporation. The Quickturn case involved a no hand poison pill provision.

Do we want additional materials on poison pills (e.g. Carmody Brothers etc.)? For present purposes, this is more about board power over shareholder voting than the operation of poison pills. Maybe we should have a diagram for a poison pill in the 2d ed.

Summary

The main ideas in this chapter are:

o Power of BOD to interfere when SH have voting rights is significantly limited o Duties imposed on directors with regard to SH voting are more burdensome than the other tests o Justified only if the board shows compelling circumstances o BOD cannot disenfranchise SH by limiting the power of future boards o Cannot limit fiduciary duties and prerogatives of the BOD

o Understanding the various forms of acquisition, and the rights of shareholders in both the acquiring corporation and the target corporation.

26