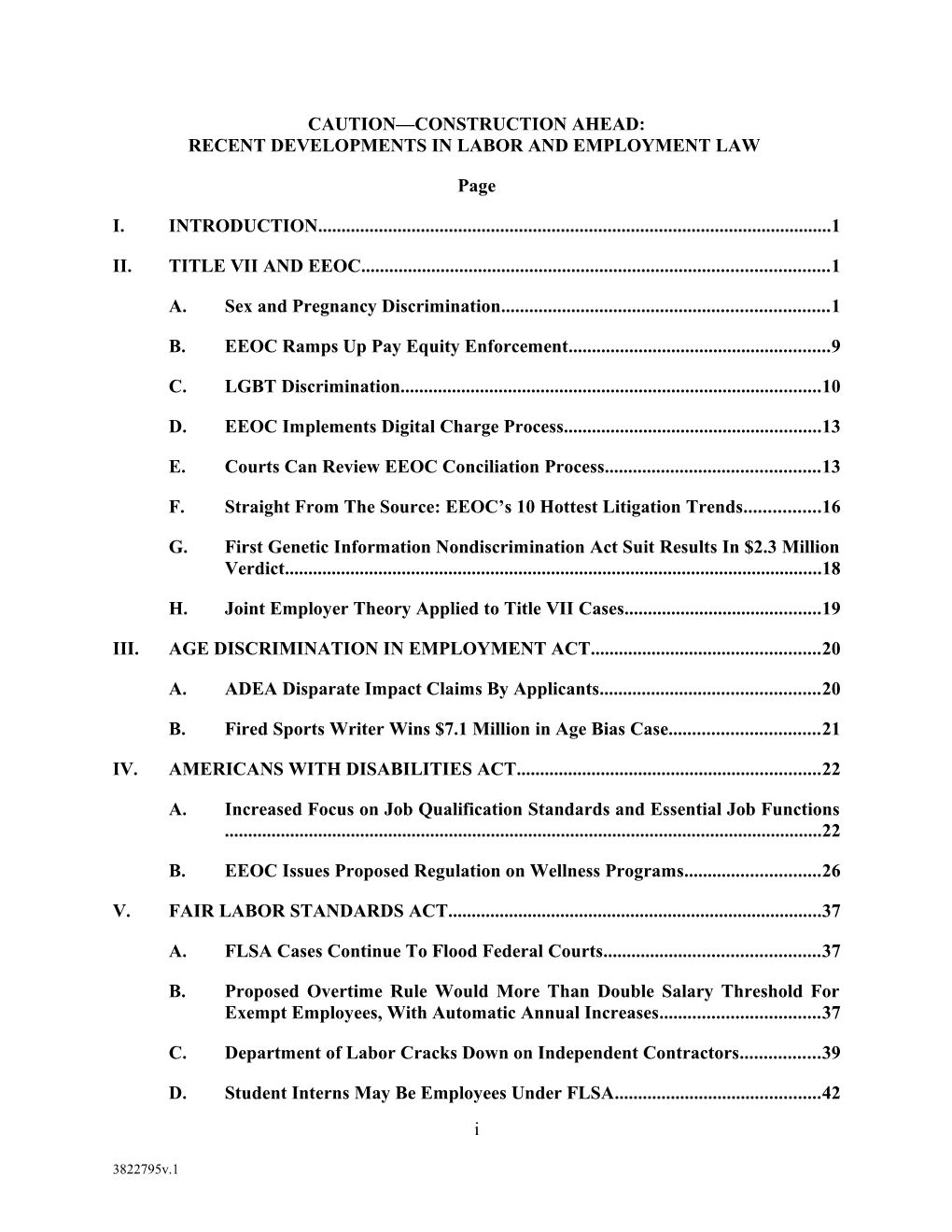

CAUTION—CONSTRUCTION AHEAD: RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT LAW

Page

I. INTRODUCTION...... 1

II. TITLE VII AND EEOC...... 1

A. Sex and Pregnancy Discrimination...... 1

B. EEOC Ramps Up Pay Equity Enforcement...... 9

C. LGBT Discrimination...... 10

D. EEOC Implements Digital Charge Process...... 13

E. Courts Can Review EEOC Conciliation Process...... 13

F. Straight From The Source: EEOC’s 10 Hottest Litigation Trends...... 16

G. First Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act Suit Results In $2.3 Million Verdict...... 18

H. Joint Employer Theory Applied to Title VII Cases...... 19

III. AGE DISCRIMINATION IN EMPLOYMENT ACT...... 20

A. ADEA Disparate Impact Claims By Applicants...... 20

B. Fired Sports Writer Wins $7.1 Million in Age Bias Case...... 21

IV. AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT...... 22

A. Increased Focus on Job Qualification Standards and Essential Job Functions ...... 22

B. EEOC Issues Proposed Regulation on Wellness Programs...... 26

V. FAIR LABOR STANDARDS ACT...... 37

A. FLSA Cases Continue To Flood Federal Courts...... 37

B. Proposed Overtime Rule Would More Than Double Salary Threshold For Exempt Employees, With Automatic Annual Increases...... 37

C. Department of Labor Cracks Down on Independent Contractors...... 39

D. Student Interns May Be Employees Under FLSA...... 42 i

3822795v.1 E. Home Health Care Workers Employed by Third Parties Have a Right to Minimum Wage and Overtime...... 43

F. Paying Wages With Debit Cards May Violate FLSA...... 46

G. Department of Labor Issues Joint Employer Guidance...... 47

H. Supreme Court Rule Limits Ability to Squelch Class Action Lawsuits...... 48

VI. NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS ACT AND NLRB...... 48

A. NLRB Changes Joint Employment Standard, With Far-Reaching Implications For Employers...... 48

B. Department of Labor To Issue New “Persuader” Regulation...... 50

C. NLRB Attacks on Employer Policies for Union and Non-Union Employers.52

D. Social Media Policies...... 57

E. NLRB Accepts Electronic Signatures...... 61

F. NLRB Quickie Election Rule Results In Quicker Elections and More Union Victories...... 63

G. NLRB Rules That Dues Checkoff Continues After Termination of Collective Bargaining Contract, Absent Express Provision...... 63

H. War Continues Over Class Action Waivers in Arbitration Agreements...... 64

I. NLRB Dismisses Northwestern University Football Players’ Petition For Union Election...... 65

VII. FAMILY AND MEDICAL LEAVE ACT...... 66

A. FMLA Protects Job Applicants From Retaliation...... 66

B. Employee Can Sue for FMLA Interference Even if Leave Ultimately Granted ...... 67

C. Does an Employee Get to Choose Whether to Use FMLA Leave?...... 68

VIII. OSHA...... 70

A. OSHA Rule Requiring Employers To Post Injury And Illness Info Online May Be Coming Soon...... 70

B. 2015 Budget Agreement Permits 82 Percent Increase In OSHA Penalties....72

ii

3822795v.1 C. OSHA Issues Guidance on Transgender Employee Restroom Access...... 73

IX. GOVERNMENT CONTRACTING / OFCCP...... 75

A. OFCCEP Issues Regulations on “Pay Transparency”...... 75

X. EMPLOYEE BENEFITS LAW...... 78

A. Affordable Care Act Developments...... 78

B. Supreme Court Limits Ability of Health Plans to Seek Reimbursement...... 80

XI. WHISTLEBLOWER CLAIMS...... 80

A. Directors May Be Personally Liable Under SOX and Dodd-Frank...... 80

B. Dodd-Frank May Protect Internal Whistleblowers...... 81

XII. ON THE HORIZON...... 81

iii

3822795v.1 CAUTION—CONSTRUCTION AHEAD: RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT LAW

“If you’re interested in the living heart of what you do, focus on building things rather than talking about them.” — Ryan Freitas, About.me Co-Founder

I. INTRODUCTION

In building or maintaining a solid human resources function, it is critical that employers keep up with new developments in labor and employment law. New employment statutes, regulations, guidelines, and court decisions are handed down on virtually a daily basis.

Employers are required to digest and learn to cope with these developing legal rules, for failure to do so can potentially be disastrous. For this reason, each year we devote much attention to providing seminar participants with a brief review of some of the most significant legislative, regulatory, and case law developments in the area of labor and employment law during the past twelve or so months.

II. TITLE VII AND EEOC

A. Sex and Pregnancy Discrimination

In March, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Young v. United Parcel Service that employers covered by the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (part of Title VII) may be required to make reasonable accommodations for work restrictions caused by pregnancy and related conditions.

The majority opinion in Young v. United Parcel Service says that failure to make pregnancy accommodations may be a form of unlawful sex discrimination. However, the Court failed to articulate a clear standard of when accommodation is required.

1

3822795v.1 1. Facts of the Case

Peggy Young was an air package delivery driver for UPS, working out of Alexandria,

Virginia. Her job required her to regularly lift packages weighing as much as 70 pounds, and to move packages weighing up to 150 pounds with assistance. After suffering several miscarriages,

Ms. Young became pregnant, and she was placed on a 20-pound lifting restriction, which was later changed to a 10-pound restriction. UPS did not terminate her employment, but it did require her to go on an unpaid medical leave of absence and did not offer accommodations that would have allowed her to continue working.

Ms. Young and her co-workers were subject to a collective bargaining agreement, which provided for reasonable accommodations for (1) disabilities within the meaning of the

Americans with Disabilities Act, (2) on-the-job injuries, and (3) employees who were unable to drive because they had lost their certifications under U.S. Department of Transportation regulations. Ms. Young sued in federal court, alleging pregnancy discrimination among other claims. The pregnancy issue was the only one reviewed by the Supreme Court.

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which took effect in 1979, amended Title VII’s sex discrimination provisions to include pregnancy, childbirth, and related conditions. It states as follows:

[W]omen affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions shall be treated the same for all employment-related purposes, including receipt of benefits under fringe benefit programs, as other persons not so affected but similar in their ability or inability to work . . ..

In 1979, the Americans with Disabilities Act, with its requirement that employers make reasonable accommodations for disabilities, was still in the future (the ADA was enacted in 1990 and did not first take effect until 1992), so at the time that the PDA was enacted, Congress was

2

3822795v.1 presumably focused on preventing differential treatment of pregnant women – including refusals to hire or promote, or forcing women to resign when they became pregnant or gave birth.

Over the years, most courts have interpreted the PDA to require that pregnant employees be treated the same as any other employee with a temporary, non-work-related disability. If an employer made “accommodations” for such conditions, then it would have been required to do the same for a pregnant employee who needed accommodation. But employers were generally not required to treat pregnancy the same way they treated ADA disabilities, or work-related injuries or illnesses. More recently, there had been growing support for requiring employers to make reasonable accommodations for pregnancy-related conditions, just as they would for employees with disabilities. A number of state and local governments have enacted “pregnancy accommodation” laws, but the U.S. Congress has not.

A federal court in Virginia granted summary judgment to UPS, and the U.S. Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit – which hears appeals from federal courts in Maryland, North

Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia – affirmed. According to the Fourth

Circuit, neither employees with ADA disabilities, nor employees with work-related injuries, nor employees with DOT restrictions were similarly situated to employees who had pregnancy- related work restrictions. Thus, the Fourth Circuit held UPS did not “discriminate” against Ms.

Young by requiring her to go out on unpaid leave. Ms. Young sought review by the Supreme

Court, who agreed to hear the case, and oral argument was held in December 2014.

2. The Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court vacated the Fourth Circuit decision and sent the case back for resolution in accordance with the Supreme Court decision. The majority opinion was written by

Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg,

3

3822795v.1 Elena Kagan, and Sonya Sotomayor. Justice Samuel Alito wrote a separate opinion concurring in the judgment. Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Justices Anthony Kennedy and Clarence

Thomas, dissented. Justice Kennedy also wrote a separate dissent, for the most part stressing that he did not philosophically oppose the idea of workplace accommodation of pregnancy. Ms.

Young had argued that, if an employer accommodated any subset of workers, then it should be required to accommodate pregnant workers with similar limitations. The majority rejected this argument, saying that it granted pregnant women “most-favored nation status,” which was not authorized under the PDA.

The majority also declined to apply the EEOC’s new Enforcement Guidance on

Pregnancy Discrimination and Related Issues, which among other things takes the position that an employer must accommodate pregnancy if it accommodates employees with disabilities and must provide light duty for pregnant employees if it does so for employees with workplace injuries and illnesses. However, it was not clear that the majority actually disagreed with the

EEOC’s position. Instead, the majority seemed to primarily object to the fact that the EEOC’s

Enforcement Guidance represented a dramatic change in the agency’s prior position on pregnancy discrimination and that there was no explanation for the change. (The majority also did not seem to care for the fact that the EEOC issued the Enforcement Guidance after the

Supreme Court had already agreed to hear the Young case.)

On the other hand, the majority rejected as too narrow UPS’s argument that the PDA did nothing more than add “pregnancy, childbirth, and related conditions” to the definition of “sex discrimination” prohibited by Title VII. The Court majority said that a woman claiming discrimination based on failure to accommodate pregnancy would be required to establish the following:

4

3822795v.1 that she was a member of the “protected class” (that is, pregnant, or having a pregnancy-

related condition);

that she sought a reasonable accommodation;

that the employer did not accommodate her; and

that the employer did accommodate others “similar in their ability or inability to work.”

As an example, presumably an employee with a 20-pound lifting restriction because of degenerative disc disease (arguably a “disability” within the meaning of the ADA) would be

“similar in his ability or inability to work” to a pregnant employee with a 20-pound lifting restriction. If the employee could make out this prima facie case, the employer could articulate a legitimate, non-discriminatory reason for treating the pregnant employee differently. The majority gave virtually no guidance here, but again, using the example of the co-worker with degenerative disc disease, perhaps the employer could argue that the employees were treated differently because the ADA mandated accommodation in the case of the employee with a chronic back condition. The employer might also be able to argue that the conditions were different because the back condition would last indefinitely and might even worsen over time, while the pregnancy-related condition would presumably be resolved in a few months. The Court majority did say that the expense or inconvenience of accommodating pregnant employees was not a legitimate, non-discriminatory reason for a distinction.

Finally, the majority said that if the employer met its burden, the employee could nonetheless prevail by showing that the employer’s explanation was a “pretext” for discrimination. This is where the Court’s decision became particularly maddening for its lack of concrete guidance and somewhat circular reasoning: according to the Court, pretext can be shown if (1) the policy imposes a significant burden on pregnant workers, and (2) the employer’s

5

3822795v.1 legitimate, non-discriminatory reasons are not strong enough to justify the burden. Among other things, the Court majority said an employee could show pretext by presenting evidence that the employer accommodated a large percentage of non-pregnant workers while accommodating a relatively small percentage of pregnant workers. Or an employee could show that the employer has multiple policies about accommodations for non-pregnant workers while having no pregnancy accommodation policies. The Court sent the case back to the Fourth Circuit for a determination as to whether UPS’s policy was a pretext for pregnancy discrimination.

Justice Alito, in his separate concurrence, indicated that an employer might be able to make distinctions among employees based on the “reason” for the restriction. He gave the example of an employer who might make accommodations for employees who had become restricted based on heroic conduct, such as military service. He also indicated that employers should be allowed to treat employees with ADA disabilities or on-the-job injuries or illnesses differently from pregnant employees. (The EEOC took exactly the opposite approach in its

Enforcement Guidance, calling these types of distinctions unlawful “source discrimination.”)

However, Justice Alito agreed with the majority that there was no meaningful distinction between UPS’s “DOT-restricted” employees and pregnant employees.

3. What Does It All Mean? Most employers probably would have preferred either the old rule that pregnancy should be treated the same as any other temporary, non-work-related disability, or a rule that required employers to make reasonable accommodations for pregnancy-related restrictions, period, which at least would have the benefit of clarity. Instead, the majority’s vague standard will probably not be clarified for years, until post-Young pregnancy cases begin working their way through the lower courts.

6

3822795v.1 It is also questionable whether the Court’s decision will deter the EEOC from continuing to take its current aggressive, pro-accommodation stance: the agency may remedy the deficiencies noted in its Enforcement Guidance by simply adding a paragraph explaining the reason for its change in position on pregnancy accommodation and acknowledging the Young decision, saying that Young supports the EEOC’s new stance. That having been said, a few principles may be gleaned from the decision:

Employers in states or localities that already have pregnancy-accommodation laws should comply with their state or local laws. More protections may be available to employees under state or local laws than under federal law. If so, compliance with state or local law should also result in compliance with federal law.

Employers who are not governed by state or local pregnancy-accommodation laws:

may be able to continue treating employees with ADA-covered disabilities and work-

related conditions more favorably than they do pregnant employees, based on Justice

Alito’s concurring opinion. However, they should be aware that the EEOC has taken the

opposite position, and it is not clear that the rest of the majority agreed with Justice Alito

on this point, either. Therefore, this approach involves some legal risk.

should accommodate pregnancy or related conditions if the employers make

accommodations for any class of employees other than ADA-disabled employees or

employees with work-related conditions.

should consider taking a low-risk course and complying with the EEOC’s Enforcement

Guidance, on the chance that the EEOC will simply “re-adopt” its position with minor

updates.

7

3822795v.1 Employers should review their accommodation policies and practices in light of the Young decision and adapt as necessary.

In a case decided shortly after the Supreme Court decision in Young v. United Parcel

Service, Inc., a federal judge applied the Supreme Court’s reasoning. In LaSalle v. City of New

York (2015), the court ruled that a female van driver for the New York City morgue who alleged she was denied accommodation for a lifting restriction while pregnant adequately stated discrimination claims under the federal Pregnancy Discrimination Act and New York state and

City laws. Partly denying the City's motion to dismiss, the court said that the U. S. Supreme

Court decision in Young v. United Parcel Service Inc ., “dispelled any doubt” an employee may bring a PDA claim based on her employer's alleged failure to accommodate pregnancy-related work restrictions.

In the LaSalle case, the plaintiff alleged that after she became pregnant in November

2011, she asked not to be assigned to drive the morgue van because doctors had recommended she lift no more than 45 pounds. She alleged that her supervisors continued to order her to drive the van, and in January 2012, she was injured while transporting a cadaver. When LaSalle sought to return to work in April 2012, she presented a doctor's note recommending a 25-pound lifting restriction, but her supervisors said no “light duty” was available. The court reasoned that

LaSalle sufficiently stated a pregnancy bias claim under the PDA and disability bias claims under the New York State Human Rights Law and New York City Human Rights Law.

The City argued LaSalle's disability discrimination claims should fail because her requested accommodations—that she not be required to drive the van or to lift more than 25 pounds—would have prevented her performance of the job's essential functions. But LaSalle received similar accommodations during a 2008 pregnancy, and in June 2012, the City granted

8

3822795v.1 her “virtually identical accommodations” when it ultimately allowed her return to work, the court said. The City offers “no explanation as to why [LaSalle's] requested accommodations were reasonable in 2008 and in June 2012, but were not reasonable when [LaSalle] requested them in

December 2011 and April 2012,” the court said.

B. EEOC Ramps Up Pay Equity Enforcement

On Friday, January 29, 2016, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission released a proposed rule that will require employers with more than 100 employees to include pay data by race, ethnicity, and sex in their annual EEO-1 reports. The EEOC will use this data to identify employers with pay disparities that might be a result of discrimination.

The proposed rule would take effect beginning with the EEO-1 reports that come due on

September 30, 2017. (There will be no change for September 30, 2016.) Under the proposal, employers would be required to include W-2 earnings information for a single pay period between July 1 and September 30, the same reporting "window" that applies now to other EEO-1 information. The EEOC says that it settled on W-2 earnings because they are more complete than the alternatives, and include overtime, severance, bonuses, taxable fringe benefits, and the like.

The proposal would categorize employees into 12 pay bands across the EEO-1 categories. According to the EEOC, use of pay bands will be less burdensome for employers and will also provide more meaningful pay data to the EEOC. In addition to number of employees

(by race, ethnicity, and sex) in each pay band, the employers will be required to state the number of hours worked. The agency has requested input from employers on how to state or calculate number of hours worked for "salaried" employees and suggests that employers assume they work

40 hours a week. (Presumably, the problem is really with "exempt" rather than "salaried"

9

3822795v.1 employees; salaried employees can be nonexempt and, if so, the employer already has to track their hours.) The EEOC also proposes to require that all EEO-1s be filed electronically starting in 2017.

As federal contractors know, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs issued a proposed rule in 2014 that would have required disclosure of pay data on EEO-1 reports by federal contractors with 100 employees or more. The EEOC rule, if adopted, would replace the

OFCCP proposal.

Comments on the EEOC's proposed rule will be accepted through April 1, 2016.

Getting ready

It's not too early for employers to begin auditing their pay practices with the help of employment counsel. At a minimum, these audits should include identifying any disparities that appear to be based on race, sex, or ethnicity. Look at employees in the same job, but because the trend seems to be "comparable worth" rather than "equal pay for equal work," it's a good idea to also compare employees who perform arguably "similar" work. Where an apparent disparity has a valid explanation, make sure you have gathered the documentation necessary to explain it to the EEOC or other government agency – or a plaintiff's lawyer. Where an apparent disparity does not have a valid explanation, work on correcting the disparity and determine how to explain the correction to the affected employee.

C. LGBT Discrimination

Last year, we reported on a lawsuit filed by the EEOC against Lakeland Eye Clinic of

Florida alleging that the termination of a transgender employee violated Title VII. In April,

2015, the lawsuit against Lakeland Eye Clinic of Florida was settled. The Clinic agreed to make two payments of $75,000 to Brandi Branson, who had been the Clinic’s Director of

10

3822795v.1 Hearing Services. Ms. Branson was hired as a male and began transitioning to female after about six months on the job. The lawsuit claimed that doctors all but stopped referring patients to her and that her position was eventually eliminated in a bogus reduction in force (a replacement was reportedly hired into the “eliminated” position only two months later). The EEOC alleged that the Clinic violated Title VII by discriminating against Ms. Branson because of her sex (failure to conform to gender stereotypes). In addition to the payments, the Clinic agreed to adopt a policy against discrimination because of gender identity or gender stereotyping, and to conduct training for management and employees on the subject.

In other federal government efforts to deal with LGBT discrimination, the Office of

Federal Contract Compliance Programs now requires federal contractors to include sexual orientation and gender identity as protected classes in EEO statements, purchase orders, and other required documentation, and to provide training. Also, EEOC charges alleging LGBT discrimination are increasing.

However, the law remains unsettled whether Title VII’s ban on “sex discrimination” applies to LGBT discrimination. There is no federal statute explicitly barring LGBT discrimination. A number of courts have found that Title VII’s ban on sex discrimination does apply to discrimination based on failure to conform to gender stereotypes and norms — precisely the issue involved in the EEOC lawsuit against Lakeland Eye Clinic. But it is far less clear that

Title VII applies to garden-variety “sexual orientation discrimination” where no “gender stereotyping” is involved. However, the EEOC seems determined to expand the law in that direction.

In July, 2015, the EEOC issued a ruling in Complainant v. Fox (2015) that Title VII’s ban on gender discrimination prohibits bias based on sexual orientation. The EEOC decision

11

3822795v.1 reasoned that sexual orientation discrimination is a form of sex discrimination under Title VII independent from the sex stereotyping theory which has been utilized by the EEOC and federal courts when finding that LGBT discrimination is a form of sex discrimination.

In January, 2016, the EEOC filed an amicus brief with the Eleventh Circuit Court of

Appeals in Burrows v. College of Central Florida. In that amicus brief, the EEOC argued that employment bias based on an individual’s sexual orientation is sex discrimination under Title

VII. The Burrows case is on appeal from a ruling of a federal district court in Florida that dismissed the plaintiff’s claim that she was treated differently because of her sexual orientation and same-sex marriage. In that case, the lower court ruled that sexual orientation discrimination is not covered by Title VII.

On January 14, 2016, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals essentially held that transgender discrimination is a form of sex discrimination under Title VII when it reversed a summary judgment dismissing an employee’s claim that she had been terminated because of her transgender status. In Chavez v. Credit Nation Auto Sales, LLC (2016), the Eleventh Circuit ruled that the plaintiff presented sufficient evidence of pretext to warrant a trial based on comments by her supervisor about being nervous about the effect on the business of her transition to a different gender and her excellent pre-transition performance reviews. In the

Chavez case, the plaintiff was told that she could no longer use a unisex restroom that other female employees were permitted to use; she was asked not to wear a dress or anything

“outlandish;” and asked to tone down her workplace conversations about her upcoming surgeries. The Eleventh Circuit ruled that this represented sufficient evidence of pretext to justify sending the case back to the district court for a trial. The Court of Appeals implicitly

12

3822795v.1 ruled that transgender status is protected under Title VII independent of a sex stereotyping legal theory.

D. EEOC Implements Digital Charge Process

The EEOC has begun use of a new "Digital Charge" for employment discrimination charges filed against non-federal employers. Under the "Digital Charge" process, an employer will no longer receive the usual forms informing it that a charge of discrimination has been filed against it. Instead, an employer will receive just a one-page letter titled "Notice of Charge of

Discrimination" that will include a link to view the entire charge online via a secure portal. This portal, which is shared between the employer and the EEOC, is to be used by the employer not only to view the full charge of discrimination, but also to submit electronically any documents to the EEOC, including notices of appearance, requests for extension of time, supporting documentation, and the employer's position statement.

E. Courts Can Review EEOC Conciliation Process

In May, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the EEOC’s longstanding position that pre-suit conciliation efforts are shielded from judicial review of any kind. Holding that “a court may review whether the EEOC satisfied its statutory obligation to attempt conciliation before filing [an employment discrimination] suit,” the unanimous opinion of Mach Mining, LLC v.

EEOC makes clear that judicial review is the only way to ensure EEOC compliance with pre-suit obligations. The opinion, written by Justice Elena Kagan, also establishes the general scope of any such review – and even suggests ways for the EEOC to prove compliance and for the employer to rebut. Even so, Mach Mining leaves many issues related to the EEOCs pre-suit obligations unresolved.

13

3822795v.1 1. Fact of the Case

A female applied for a job as a coal miner with Mach Mining and was not hired. She filed a sex discrimination charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The EEOC issued a “reasonable cause” determination on behalf of the woman who filed the original charge as well as a class of women who applied for mining jobs. After sending two letters, one advising the company of the EEOC’s reasonable cause determination and another declaring conciliation efforts unsuccessful, the EEOC filed suit in a federal court in Illinois.

The EEOC alleged in its complaint that it tried to conciliate before filing suit, but Mach

Mining denied that the agency “conciliated in good faith.” The EEOC sought summary judgment on the issue, claiming that courts should not be allowed to review the agency’s conciliation efforts. The district court disagreed, and found that it was entitled to determine whether the

EEOC made “a sincere and reasonable effort to negotiate.” The EEOC appealed to the U.S.

Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, which hears appeals from federal courts in Illinois,

Indiana, and Wisconsin. The Seventh Circuit reversed, and found that there was no right of judicial review of the EEOC’s conciliation efforts. (The U.S. Courts of Appeals for the Fourth,

Sixth, and Tenth circuits found in previous decisions that a very limited degree of judicial review was appropriate, while the Second, Fifth and Eleventh circuits permitted a more in-depth review.)

2. The Supreme Court Decision

Mach Mining petitioned for the Seventh Circuit decision to be reviewed by the U.S.

Supreme Court, and the Supreme Court unanimously reversed the Seventh Circuit decision.

However, the Court found that the appropriate remedy when the EEOC failed to conciliate was

14

3822795v.1 not dismissal of the lawsuit but an order requiring the EEOC to conciliate before moving forward.

The Supreme Court first discussed the “strong presumption” in favor of judicial review of administrative actions that may be rebutted only if the agency demonstrates Congress’ intent for an agency to “police its own conduct.” The Court ruled that the EEOC failed to demonstrate a

Congressional intent exempting its conciliation efforts from all judicial review. The Court said that the EEOC must disclose to the employer the alleged unlawful employment practice at issue and provide the employer with an opportunity to discuss it, all in an effort to achieve voluntary compliance with the law. Without the option of judicial review, the Court notes, violations of these requirements by the EEOC would have no consequence.

That said, the Court clarified that judicial review of the EEOC’s conciliation efforts should be narrow in scope. The conciliation process must “afford the employer a chance to discuss and rectify a specified discriminatory practice – but goes no further.” The court should

“respect the expansive discretion that Title VII gives to the EEOC over the conciliation process, while still ensuring that the [EEOC] follows the law.” The purpose of judicial review is to

“determine that the EEOC actually, and not just purportedly, tried to conciliate a discrimination charge.” In short, the Court makes clear that the EEOC need only “endeavor” to conciliate a claim, without a set amount of time or resources, without requiring specific steps or measures, and with the discretion to sue whenever “unable to secure” terms “acceptable” to the EEOC.

3. Going Forward

The Court’s decision suggests what the EEOC should and should not do in proving that it complied with its duty to conciliate. According to the Court, the EEOC may prove compliance by submitting an affidavit saying that it met its obligations by attempting in good faith to

15

3822795v.1 conciliate but that conciliation efforts failed. If the EEOC’s affidavit is rebutted with “credible evidence” from the employer, the trial court must then “conduct the factfinding necessary to decide that limited dispute.” What these phrases mean will no doubt result in another split among the circuits.

The opinion does, however, resolve the split in the circuits with regard to the appropriate remedy if the EEOC fails to satisfy its conciliation obligation. Previously, some courts were

“staying” (suspending) the case while the EEOC fulfilled its obligations. Other courts dismissed the lawsuit altogether. As already noted above, the Supreme Court ruled that “the appropriate remedy is to order the EEOC to undertake the mandated efforts to obtain voluntary compliance” rather than dismissal.

The Mach Mining opinion leaves many issues unresolved. For example, the opinion does not address the EEOC’s statutory and separate pre-suit obligation to investigate the merits of a charge or the appropriate remedy if the EEOC fails to do so. Likewise, the Court does not address whether the EEOC’s obligations are different depending upon whether it seeks prospective relief (to prevent future discrimination) or retrospective relief (like monetary damages for back pay) on behalf of claimants. Finally, the Court does not discuss what discovery is permitted of the EEOC’s conciliation (or investigative) efforts, an issue on which the circuits do not agree.

Those questions aside, the Supreme Court Mach Mining decision is an important victory for employers.

F. Straight From The Source: EEOC’s 10 Hottest Litigation Trends

In October, 2015, David Lopez, General Counsel of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, spoke at an employment law conference in which he outlined the EEOC’s litigation

16

3822795v.1 priorities in enforcing Title VII. Mr. Lopez presented his top 10 issues in reverse order, from least to most significant.

10. Racial harassment. Mr. Lopez noted that the EEOC had scored some big wins in this area, generally when the racially offensive behavior was blatant. “Juries don’t like this kind of behavior,” he said. On the other hand, he said, there was much less consensus about “subtler” forms of harassment and discrimination.

9. Use of background screens in hiring. Mr. Lopez acknowledged that many of the cases hadn’t gone the EEOC’s way, but said the agency had “started a conversation” about the use of this information, noting the growing number of states that have adopted “ban-the-box” legislation.

8. Sex discrimination in hiring. Mr. Lopez said that the agency is aggressively going after claims of discrimination in the hiring process because most plaintiffs’ attorneys lack the time and resources to get proof of systemic discrimination and individual cases are not lucrative. He also mentioned litigation in heavy manufacturing environments, where women were rejected for positions based on the belief that they could not handle the physical requirements of the job.

7. Preservation of access to the legal system, aka retaliation. Retaliation has always been a very high priority issue for the EEOC. In the agency’s view, it can’t do its job if people are deterred from making complaints about discrimination in the workplace or coming to the EEOC. Mr. Lopez said that the EEOC was winning about 70 percent of its jury trials on retaliation claims.

6. Immigrant/migrant/“vulnerable” workers. Mr. Lopez spoke of the EEOC’s desire to protect workers “living in the shadows,” and noted that some employers believe they can evade the law because of linguistic and cultural barriers. He cited an EEOC victory from 2013 against Moreno Farms in Florida, in which a jury awarded five women who were allegedly sexually harassed and raped a total of $17 million. (The farm went under immediately afterward, so it’s not clear that the women got any relief.)

5. Americans with Disabilities Act/reasonable accommodation. Mr. Lopez spent most of this topic talking about the EEOC v. Ford Motor Company telecommuting case involving an employee with severe irritable bowel syndrome. Summary judgment was granted to Ford by the district court, and a three-judge panel of the Sixth Circuit reversed. But Ford asked to have the case heard by all of the judges on the Sixth Circuit, and the majority agreed with the district court. Mr. Lopez expressed frustration that the full appeals court would not take judicial notice (in other words, they wouldn’t rule on the issue without evidence) of the fact that technology had changed to such a degree that telecommuting is a better reasonable accommodation than it used to be. He also disagreed with the court’s finding that a company shouldn’t be penalized because it allows telecommuting in some cases but not others.

4. LGBT rights. Mr. Lopez said that the EEOC’s position is that sexual orientation discrimination always violates Title VII. Interestingly, Mr. Lopez claimed support for the 17

3822795v.1 agency’s position from — Antonin Scalia! In the Supreme Court decision of Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services (1998), the Court decided that a plaintiff could sue for sex harassment under Title VII when he was harassed by his male co-workers for being too “effeminate.” (The plaintiff was not gay, so sexual orientation was not at issue. Gender stereotyping was.)

Mr. Lopez also spoke on the issue of bathrooms and transgender individuals. The EEOC’s position is that transgender individuals have the right to use the restroom of their choice, no matter where they are in the transition process. (In other words, they don’t have to have had surgery yet to be entitled to use a different restroom.)

3. Pregnancy. This is obviously a very hot area after the Young v. UPS case. Mr. Lopez said that many employers (smaller ones) still don’t know that “Yes, pregnancy discrimination is against the law.” Young was a “game-changer,” Mr. Lopez said, because it gave new life to the second part of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which requires treatment of pregnant women that is the same as the employer’s treatment of non-pregnant employees who are “similar in their ability or inability to work.”

2. Conciliation requirement. Mr. Lopez said that the victory for employers was that the SCOTUS said the courts do have authority to review the EEOC’s conciliation efforts. The victory for the EEOC, though, was that if the EEOC doesn’t fulfill its obligations, the court just tells the EEOC to go back and conciliate rather than dismissing the lawsuit.

1. Religious accommodation. “This is number one in my heart,” Mr. Lopez said. He was talking about Samantha Elauf, in the EEOC’s case against Abercrombie & Fitch, which we discussed in our 2015 Employment Law Workshop.

G. First Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act Suit Results In $2.3 Million Verdict

In what is believed to be the first jury verdict in a lawsuit filed under the Genetic

Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), a federal court jury in the Northern District of

Georgia awarded $2.3 million to two employees who were ordered to provide saliva samples as part of an internal investigation. In Lowe v. Atlas Logistics Group Retail Services (2015), the company was conducting an internal investigation to determine who was defecating on the floor of its warehouse, which resulted in the destruction of grocery products. The company suspected that the two plaintiffs may have been involved in the misconduct. It ordered the two plaintiffs to

18

3822795v.1 submit to the collection of saliva samples without informing of their rights under GINA. The two men were subsequently determined not to be involved.

The federal district court ruled against the company on summary judgment, and rejected the company’s argument that the tests used on the plaintiffs’ saliva samples did not detect medical information; or uncover the propensity of the plaintiffs to develop a disease; or discover whether the plaintiffs’ offspring would have a genetic mutation. After the granting of summary judgment in favor of the plaintiffs, the trial was conducted solely on damages. At the end of that trial, the jury awarded each plaintiff $250,000 for damages for emotional pain and suffering and awarded a total of $1.75 million in punitive damages.

H. Joint Employer Theory Applied to Title VII Cases

The National Labor Relations Board has received much publicity about its effort to expand the joint employer test to hold employers legally responsible for violations of law by contractors and franchisees. Less noted is the fact that the Department of Labor has applied a joint employer rationale to hold employers responsible for violations of the Fair Labor Standards

Act by contractors; and federal courts have held employers liable under Title VII for actions by their contractors on a joint employer theory.

In November, 2015, the joint employer theory was used by a federal judge in Tampa to hold that Sarasota Doctors’ Hospital was liable for the Title VII violations of one of its contractors in Scott v. Sarasota Doctors’ Hospital (2015). In that case, the federal district judge denied summary judgment to Sarasota Doctors’ Hospital in a suit filed by an employee of one of the hospital’s third-party contractors. The court ruled that a reasonable jury could find that the hospital exercised sufficient control over the plaintiff’s employment and the decision to terminate her employment to be deemed a joint employer under Title VII.

19

3822795v.1 In Scott, the Plaintiff was a physician who was placed at Sarasota Doctors’ Hospital by

Emcare, Inc. as a contract physician. After a short period of time, the Emcare on-site manager received complaints from the hospital that Scott was too curt with patients and nurses, and hospital officials expressed concern about her “fit” at the hospital. After Scott filed a discrimination charge claiming that a male doctor was treated differently, the hospital directed

Emcare to terminate her assignment at the hospital. In denying summary judgment, the court relied on the fact that the hospital controlled her employment by directing Emcare to terminate her employment at the hospital.

III. AGE DISCRIMINATION IN EMPLOYMENT ACT

A. ADEA Disparate Impact Claims By Applicants

On November 30, 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, which hears appeals from cases in Florida, Georgia and Alabama, held that job applicants may bring disparate impact claims against employers under the Age Discrimination in Employment Act in Billarreal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (2015). In Billarreal, the plaintiff had applied for a job as a sales territory manager. He was 49 years old at the time he applied. He subsequently discovered that R.J. Reynolds had encouraged hiring managers, in filling territory managers sales positions, to target younger applicants and to stay away from applicants with eight to ten years of sales experience. As a result, he filed an EEOC charge based on age and subsequently filed suit against R.J. Reynolds alleging both disparate treatment and disparate impact claims on behalf of himself and other similarly situated older applicants. The federal district court dismissed

Billarreal’s disparate impact claim, holding that the ADEA does not recognize disparate impact claims by job applicants although it does recognize disparate impact claims by current employees. Billarreal appealed to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Eleventh

20

3822795v.1 Circuit reversed the federal district court’s dismissal of his ADEA disparate impact claim. The

Eleventh Circuit reasoned that although the language of the statute is not clear on whether job applicants may pursue disparate impact claims, it was deferring to the EEOC’s interpretation of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act that authorizes disparate impact claims by job applicants.

The Eleventh Circuit reasoned that Section 4(a)(2) of the ADEA prohibits an employer from limiting, segregating or classifying employees in a way that would deprive “any individual of employment opportunities,” or “otherwise adversely affect” the employee’s status as an employee, because of age. In deferring to the EEOC’s regulation interpreting the ADEA, the court noted that the EEOC regulation does not distinguish between current and potential employees, but rather extends the ability to bring disparate impact claims based on age to all individuals within the protected age group.

As a result of Billarreal, employers in the Eleventh Circuit should be aware that they need to avoid hiring policies and practices that either expressly or implicitly encourage hiring younger candidates over older candidates, as well as hiring policies and practices that result in significant statistical disparities between the number of new hires who are below the age of 40 and above the age of 40.

B. Fired Sports Writer Wins $7.1 Million in Age Bias Case

In November, 2015, the trial of fired Los Angeles Times sports columnist T.J. Simers’ age discrimination claims against the Los Angeles Times garnered a great deal of publicity.

After a six week trial, the jury returned a verdict in favor of Simers, finding that the Los Angeles

Times had discriminated against him because of age. The jury awarded $7.1 million in past

21

3822795v.1 economic damages, future economic damages, past non-economic damages and future non- economic damages.

According to an interview of the jury foreman after the trial, the evidence that weighed most heavily in favor of a verdict in favor of the plaintiff included (1) the fact that the newspaper had issued the plaintiff a final written warning over alleged misconduct before ever issuing a first warning for the same conduct; and (2) that the plaintiff’s performance reviews were consistently positive. The jury foreman offered the opinion that the way that the plaintiff was treated by the

Los Angeles Times was “just not right.”

Although this case does not tread new ground or develop new legal theories under the

Age Discrimination in Employment Act, it illustrates the risks of terminating older employees without taking the time to deal with performance issues through progressive discipline and making sure that the process is “done right.”

IV. AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT

A. Increased Focus on Job Qualification Standards and Essential Job Functions

In recent months, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has been focusing on job qualification standards that have a disparate impact on individuals with disabilities. In doing so, the EEOC is distinguishing between job qualification standards, which may have to be modified as part of the reasonable accommodation process for a job applicant, and essential job functions, which do not have to be modified in the reasonable accommodation process.

Historically, an employee or applicant has been deemed to be qualified for a position if he or she meets basic skills, training, education and job-related requirements; and if he or she is able to perform the essential functions of the position with or without reasonable

22

3822795v.1 accommodation. The EEOC has begun to focus recently on the distinction between qualifications and essential functions, reasoning that essential job functions are what an employee does on the job; while qualification standards are requirements and predicting whether the individual can perform the essential functions. Examples of qualification standards include passing a drug test, an educational requirement, a driver’s license, or a good credit history.

The distinction between job qualification standards and essential job functions has sometimes been recognized by federal courts in ADA suits, but in other times the terms have been intermingled and intertwined. For example, in EEOC v. Ford Motor Company (2015), a case that we have discussed in prior Employment Law Workshops, the Sixth Circuit Court of

Appeals ruled in 2015 that regular and predictable on-site attendance was an essential job function for a buyer who suffered from irritable bowel syndrome. In Ford Motor Company, the

Sixth Circuit appeared to intermingle on-site attendance as both an essential job function and a job qualification standard, stating that: “regular, in-person attendance is an essential function— and a prerequisite to essential functions—of most jobs.” In that case, the EEOC took the opposite position, arguing in filing suit against Ford Motor Company that being present on the job was not an essential job function, but rather a job qualification standard that Ford Motor

Company was required to accommodate. In ruling against the EEOC, the Sixth Circuit pointed out the difficulty in sometimes distinguishing between the job qualification standards and essential job functions.

The distinction is important for employers in dealing with applicants or employees who request accommodations. The law is clear that an employer is not required to eliminate an essential job function and therefore may deny an accommodation request that involves eliminating an essential job function. However, if an employer denies an accommodation

23

3822795v.1 request involving relaxing or eliminating a job qualification standard, the employer must prove that eliminating or modifying that standard would create an undue hardship on the business of the organization. This can be a heavy burden of proof.

Distinguishing between the essential functions and job qualification standards is also the subject of two other cases decided in 2015. In Roberts v. Bayhealth Medical Center, Inc. (2015), a former part-time nurse who was normally scheduled for twelve-hour shifts requested an eight- hour shift schedule, three times a week, because of a brain tumor. When her request for an accommodation was denied, she filed suit. The defendant hospital filed a motion for summary judgment in federal district court, arguing that the hospital’s twelve-hour shift requirement was an essential job function for the nurse’s position; that the plaintiff was not a qualified individual with a disability because she could not perform that essential job function of working twelve- hour shifts, and therefore was not protected by the ADA.

The federal district court in Delaware denied the hospital’s motion for summary judgment. The court refused to rule that as a matter of law, a twelve-hour shift is really an essential job function; rather, finding that there were triable disputes of fact as to whether a twelve-hour shift really was an essential function.

In a case in California which also appeared to have difficulty reconciling essential functions with job qualification standards, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit decided in Mayo v. PCC Structurals, Inc. (2015), that a welder who was fired for repeatedly threatening to kill supervisors and managers was not a qualified individual with a disability and therefore was unprotected by the ADA.

In Mayo, the plaintiff had been treated for several years for the threats that led to his termination. During a meeting in which the plaintiff claimed to have been bullied by a

24

3822795v.1 supervisor, the plaintiff became upset and made threats against the supervisor. He repeated those threats shortly after the meeting, and when questioned by a human resources manager, he stated that he could not guarantee that he wouldn’t carry out his threats. As a result, the company suspended and then ultimately terminated the plaintiff because of his repeated threats against managers and supervisors.

Mayo filed suit and the federal district court granted summary judgment in favor of the company, ruling that Mayo’s violence and threats showed that he was not qualified to work for the employer even though the threats may have been caused by his disability. In affirming the granting of summary judgment in favor of the employer, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reasoned: “An essential function of almost every job is the ability to handle stress and interact with others … an employee whose stress leads to violent threats is not a ‘qualified individual.’”

In attempting to deal with the distinction between job qualification standards with respect to which a reasonable accommodation is required, and essential job functions that require no reasonable accommodation, employers who disqualify job applicants or employees who apply for other jobs based on qualification standards might consider the following frame work for analyzing the reason for disqualification:

Define what standard screened out the applicant or employee.

Ask whether the standard screened out the individual on the basis of disability.

If so, decide whether the standard is job related and consistent with business necessity.

If it is job-related and consistent with business necessity, determine whether the individual can meet the standard or perform the job’s essential functions with reasonable accommodation.

25

3822795v.1 If so, decide whether the employer can demonstrate that providing the accommodation would be an undue hardship or otherwise show that the accommodation would not be effective in performing the essential job functions.

C. EEOC Issues Proposed Regulation on Wellness Programs

On April 20, 2015, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) published a proposed regulation that describes how Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act

(ADA) applies to employee wellness programs that are part of group health plans and that include questions about employees' health (such as questions on health risk assessments) or medical examinations (such as screening for high cholesterol, high blood pressure, or blood glucose levels). The comment period on the proposed regulation ended on June 19, 2015. The proposed regulation is available at https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/04/20/2015-

08827/regulations-under-the-americans-with-disabilities-act-amendments. The following is a summary of the key provisions of the proposed regulation.

Wellness programs must be reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.

They must have a reasonable chance of improving health or preventing disease in participating employees, must not be unduly burdensome to employees, and must not violate the ADA.

A program that collects information on a health risk assessment to provide feedback to employees about their health risks, or that uses aggregate information from health risk assessments to design programs aimed at particular medical conditions is reasonably designed. A program that collects information without providing feedback to employees or without using the information to design specific health programs is not.

Wellness programs must be voluntary.

Employees may not be required to participate in a wellness program, may not be denied health insurance or given reduced health benefits if they do not participate, and may not be disciplined for not participating.

26

3822795v.1 Employers also may not interfere with the ADA rights of employees who do not want to participate in wellness programs, and may not coerce, intimidate, or threaten employees to get them to participate or achieve certain health outcomes.

Employers must provide employees with a notice that describes what medical information will be collected as part of the wellness program, who will receive it, how the information will be used, and how it will be kept confidential.

Employers may offer limited incentives for employees to participate in wellness programs or to achieve certain health outcomes.

The amount of the incentive that may be offered for an employee to participate or to achieve health outcomes may not exceed 30 percent of the total cost of employee- only coverage.

For example, if the total cost of coverage paid by both the employer and employee for self-only coverage is $5,000, the maximum incentive for an employee under that plan is $1,500.

Medical information obtained as part of a wellness program must be kept confidential.

Generally, employers may only receive medical information in aggregate form that does not disclose, and is not reasonably likely to disclose, the identity of specific employees.

Wellness programs that are part of a group health plan may generally comply with their obligation to keep medical information confidential by complying with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule.

Employers that are not HIPAA covered entities may generally comply with the ADA by signing a certification, as provided for by HIPAA regulations, that they will not use or disclose individually identifiable medical information for employment purposes and abiding by that certification.

Practices such as training individuals in the handling of confidential medical information, encryption of information in electronic form, and prompt reporting of breaches in confidentiality can help assure employees that their medical information is being handled properly.

Employers must provide reasonable accommodations that enable employees with disabilities to participate and to earn whatever incentives the employer offers.

For example, an employer that offers an incentive for employees to attend a nutrition class must, absent undue hardship, provide a sign language interpreter for a deaf employee who needs one to participate in the class.

27

3822795v.1 An employer also may need to provide materials related to a wellness program in alternate format, such as large print or Braille, for someone with vision impairment.

An employee may need to provide an alternative to a blood test if an employee's disability would make drawing blood dangerous.

Is the proposed rule good for employers, or bad?

Pretty good overall. The EEOC has, for the most part, proposed that providing

“incentives” for employees to participate in wellness programs (both rewards and penalties, which we’ll call “carrots” and “sticks”) will be all right as long as the employer complies with the limits in the HIPAA/Affordable Care Act. In other words, incentives to that extent would, for the most part, not make the wellness program “involuntary” for ADA purposes. Which means that medical inquiries made in connection with such a wellness program will generally not violate the ADA.

One catch: The wellness program would have to be associated with a group health plan

(either insured or self-insured).

Another catch: The EEOC proposals don’t exactly match the HIPAA/Affordable Care

Act (ACA) rules, but they are reasonably close.

What are the HIPAA/ACA requirements?

Under the HIPAA/ACA scheme, there are two types of wellness programs. A

“participatory” program is one that rewards employees just participating. Hence the name. (An example would be an employer who reimburses employees for fitness club memberships.) Under the HIPAA/ACA, participatory programs can be offered without limitation, as long as they are available to all similarly situated individuals.

28

3822795v.1 The other type of program is a “health-contingent” program. There are two types of

“health-contingent” programs: (1) activity-only programs, in which the employee is rewarded for completing an activity but doesn’t have to achieve or maintain an outcome (for example, “we’ll pay you $100 if you walk a mile three days a week for a year”); and (2) outcome-based programs, in which employees are rewarded for achieving or maintaining results (for example,

“we’ll pay you $100 if you keep your BMI at or below 25 for a year, or if you quit smoking”). If the program is health-contingent, employers are allowed to offer incentives (carrots or sticks) if

1. Employees are allowed to try to qualify at least once a year; 2. The total reward offered doesn’t exceed 30 percent of the total cost of employee-only coverage under the plan (total means the employee’s and the employer’s share), and the percentage is 50 percent for tobacco prevention or reduction; 3. The program is reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease; 4. The full reward must be available for all similarly situated individuals, and reasonable alternatives must be offered to those who can’t qualify; and 5. The availability of reasonable alternatives must be disclosed in plan materials and in any disclosure telling an individual that he or she did not meet an initial outcome-based standard. Under the HIPAA/ACA, the 30 percent/50 percent incentive applies only to “health- contingent” programs. HIPAA and the ACA have no limit on rewards that apply to “participatory” programs (if the programs are available to all similarly situated individuals).

The EEOC’s proposed rule is slightly different.

What does the EEOC say?

The EEOC would allow employers to offer incentives (carrots or sticks) for employee participation in wellness programs associated with group health plans if the total reward does not exceed 30 percent of the total cost of employee-only coverage under the plan for both participatory and health-contingent plans, AND if the wellness program is voluntary. The EEOC would define “voluntary” as follows: 29

3822795v.1 1. Employees aren’t forced to participate in the wellness program,

2. Health insurance coverage is not denied or made more difficult to get if the employee chooses not to participate (with the exception of the permitted “incentives”), and

3. The employer does not take adverse action against an employee for refusing to participate.

The employer would also be required to provide a notice “that clearly explains what medical information will be obtained, who will receive the medical information, how the medical information will be used, the restrictions on its disclosure, and the methods the covered entity will employ to prevent improper disclosure of the medical information.”

The EEOC recommended “best practices”

Make sure that employees who handle medical information know their obligations under the laws. Adopt privacy policies for collection and handling of employee medical information. If medical information is stored electronically, it should be encrypted. Employees who handle medical information should not be “making decisions related to employment, such as hiring, termination, or discipline.” If this isn’t possible (for example, with a small company that has to do it all), then the employer should ensure that there is no discrimination based on an employee’s disability. Breaches of confidentiality should be promptly and effectively addressed, and the affected employees should be informed immediately. Employers should take appropriate action against an employee who breaches confidentiality, and should “consider discontinuing” their relationships with vendors who breach confidentiality. The EEOC’s proposed regulation is inconsistent with a wellness/ADA decision from the

U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit, Seff v. Broward County in 2012. Employers in the

11th Circuit states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, can follow Seff, but employers who have operations in other states are probably better off trying to follow the EEOC once its proposal becomes final. (The conflict between the EEOC and the Eleventh Circuit will eventually be resolved in the courts.)

30

3822795v.1 As if employers had not seen enough new regulations on wellness programs, on October

30, 2015, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission issued a proposed rule on employer wellness programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). The GINA proposal accompanies the proposed rule on employer wellness programs and the Americans with

Disabilities Act, which the EEOC issued in April, 2015.

When viewed from an EEO standpoint, the proposed rule is pretty good news for employers. Many employers were concerned that the GINA rule might entirely prohibit employers from offering "inducements," or incentives, to employees’ family members who provided genetic information in connection with wellness programs. The proposed rule does allow inducements for certain health information from employees' spouses (although not their children).

On the other hand, the news is not quite so wonderful from the standpoint of the Health

Insurance Portability and Accountability Act or the Affordable Care Act. The proposed GINA rule is more complicated and restrictive than the HIPAA rule and ACA requirements. The GINA proposal focuses primarily on health information gathered from spouses of employees who participate in an employer's group health plan. (The employees' own rights are primarily governed by the ADA.)

Why didn't the EEOC just issue this latest proposal as part of the ADA proposal it issued in the spring?

The GINA is more restrictive than the ADA on the right of an employer to acquire certain medical information. In addition to placing more stringent restrictions on employers, the GINA protects not only employees but also their spouses and other family members in connection with wellness programs, while the ADA generally applies to employees only. The EEOC said that when it issued proposed GINA regulations (adopted in 2010), no one commented or asked about 31

3822795v.1 the impact on spouses participating in employer wellness programs, but it says it has "received numerous inquiries" since that time.

What does the GINA proposal say?

The proposal would amend the 2010 GINA regulations by making six additions:

1) It's ok for an employer to "request, require, or purchase genetic information" in connection with employer-provided health or genetic services only if the services "are reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease."

The proposal tells us what would not be considered "reasonably designed": *It must not be overly burdensome for the employees or family members participating, *It must not be a sneaky way of (also known as "subterfuge for") violating the GINA or other anti-discrimination laws, and *It must not be "highly suspect in the method chosen to promote health or prevent disease." The EEOC provides a few examples: *Collecting information but failing to provide any follow-up or feedback to the individual who provided the information. *Requiring a burdensome amount of time from the individual, or being intrusive, or imposing excessive costs on the individual. *Existing for the sole purpose of shifting costs from the covered entity to "targeted employees based on their health."

2) It is ok for an employer to provide "inducements" (either rewards or avoidance of penalties) to encourage an employee's spouse to provide information about his or her current or past health status, if

*The spouse is enrolled in the employer's group health insurance, and *The information is provided as part of a health risk assessment associated with the group health insurance, and *The spouse provides prior knowing, voluntary, and written authorization.

32

3822795v.1 On the other hand, the employer cannot offer inducements to obtain the spouse's "genetic information," or any information about the employee’s children. (And "children" includes not only biological children, but also adopted and stepchildren.)

One point of clarification: The GINA statute and the 2010 regulations have a broad definition of "genetic information" that includes, not only "true" genetic information like genotypes and DNA tests, but also medical history or examinations of the employee's family members. For example, it is normally a violation of the GINA for an employer to ask an employee whether anyone in his family has ever had cancer. Under the GINA, this is a request for "genetic information."

It appears that the EEOC is now distinguishing "true" genetic information (for example, genotypes and DNA tests) from medical history and medical examinations. Very strict rules apply to the former, but the rules relating to the latter are not as strict. For clarity, in this article, we will call "true" genetic information exactly that, and will refer to medical history or examinations using the EEOC’s term "current or past health status."

The spouse must also provide prior knowing, voluntary, and written authorization before disclosing past or current medical status in connection with a wellness program, and the authorization form has to "describe the confidentiality protections and restrictions on the disclosure of ["true"] genetic information or disclosure of current or past health status [for which inducements are allowed]." The employer may use the same form for both types of information or examinations. But remember that if the employer or wellness provider is collecting "true" genetic information from a spouse, it must do so without providing any inducements to the employee or spouse.

33

3822795v.1 As with inducements to the employee, there are limits on the amount of "inducement" that an employer can provide based on disclosure of past or current medical history of the spouse. The total inducement can’t exceed 30 percent of the cost of providing group health insurance coverage to the employee and spouse. Here's the EEOC’s example:

If the cost of providing group health coverage to employee and spouse (or family coverage) is $14,000, then the employer cannot offer an inducement in excess of $4,200 (30 percent of $14,000).

The EEOC's proposed 30 percent limitation is generally consistent with regulations under

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act issued in June 2013, which took effect in

2014.

Under the HIPAA regulations, there is a higher inducement cap for tobacco cessation programs (50 percent), the inducement may be increased if the wellness program includes dependents, and the cap applies only to inducements offered in the context of "health-contingent" programs. The EEOC has declined to incorporate these provisions in its ADA and GINA wellness regulations. In addition, the "30 percent" is a more complicated calculation under the proposed GINA rule than under the HIPAA regulations.

3) The "30-percent limit" described above must also be apportioned between the spouses, in cases where the inducement is designed to encourage the spouse to provide information (as opposed to the employee).

The employee's share of the inducement cannot exceed 30 percent of the employer's cost of providing individual coverage. And then the spouse’s share can’t exceed the difference between the employee's share of the inducement and the total allowable inducement for spousal/family coverage. Thankfully, the EEOC provides another example:

Using the same example as above, the cost of providing family coverage was $14,000, with a total “inducement allowance” of $4,200 to employee and spouse. 34

3822795v.1 The EEOC assumes (for purposes of the example) that the cost of individual coverage to the employer was $6,000. If so, the employee’s inducement cannot exceed 30 percent of $6,000, or $1,800. Then the spouse’s inducement would be a maximum of $2,400 ($4,200 minus $1,800).

While the EEOC tried to close the loop regarding inducements for spouses, the inducement allowance continues to stray from that permitted under the HIPAA rule, which has no "allocation" requirement for spouses. In order to be comfortable with compliance, wellness programs will need to follow the strictest allowance, which now seems to be the proposed allowance under the GINA.

The last three changes are a little simpler than the first three:

4) An employer is not allowed to require an employee, spouse, or other covered dependent to sell genetic information as a condition of participating in the wellness program or receiving an inducement. The employer also can't ask the individual to waive his or her rights under the GINA.

5) That said, the employer may obtain information about a spouse's past or current health status if the spouse is (a) covered under the employer's group health plan and (b) completing a health risk assessment on a voluntary basis (in other words, as long as the authorization and inducement requirements/limits already described are complied with).

6) "Inducements" include not only cash payments, but also "in-kind" items, "such as time-off awards, prizes, or other items of value, in the form of either rewards or penalties."

The comment period on the proposed rule ended on December 29, 2015.

Although the GINA proposal does not dovetail with the HIPAA/ACA requirements, it does appear that the EEOC is trying to harmonize its mission to protect employees’ privacy rights with respect to health-related information with the strong federal policy – especially now,

35

3822795v.1 in light of the Affordable Care Act - favoring wellness programs. The following chart attempts to illustrate the differences between the various laws and regulations.

36

3822795v.1 37

3822795v.1 V. FAIR LABOR STANDARDS ACT

A. FLSA Cases Continue To Flood Federal Courts

According to reports from the Bureau of National Affairs and Employment Law 360, the number of lawsuits alleging minimum wage and overtime violations under the Fair Labor

Standards Act (FLSA) continues to increase, with a five percent increase in suits filed between

2012 and 2015. In 2014, 7964 suits were filed in federal courts nationwide, with New York

State and Florida leading the nation in the number of federal court suits filed under the FLSA.

D. Proposed Overtime Rule Would More Than Double Salary Threshold For Exempt Employees, With Automatic Annual Increases

On June 30, 2015, the Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor released its long-awaited Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, proposing changes to the executive, administrative, professional, and highly-compensated employee exemptions from the overtime requirements of the Fair Labor Standards Act. In addition to the Notice, the Department has also issued a Fact Sheet and list of Frequently Asked Questions. Final regulations are expected sometime in mid-2016. The following are key highlights of the proposed regulations.

The Salary Test

Although the proposed rule is 295 pages long, the only substantive changes are in the weekly salary that must be paid in order for an employee to qualify for the executive, administrative, and professional exemptions to the FLSA overtime requirements, and in the annual compensation that must be paid for an employee to qualify for the “highly compensated employee” exemption. The current salary threshold for the executive, administrative, and professional exemptions is $455 a week ($23,660 a year). This figure was last updated in 2004.

In the proposed rule, the Department of Labor proposes to set the minimum weekly salary at the 40th percentile of weekly earnings for all full-time salaried employees. Assuming

38

3822795v.1 that a Final Rule is issued in 2016, the minimum weekly salary for the white collar exemptions would be $970 a week ($50,440 a year), more than double the current threshold. The effect of this change, of course, would be to dramatically increase the number of employees who are entitled to overtime pay. According to some estimates, approximately 5 million more employees nationwide would qualify for overtime if the proposed rule is adopted.

While the increase in the minimum weekly salary was expected, what was more of a surprise is the Department’s proposal, for the first time since the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed in 1938, to automatically increase the minimum weekly salary requirement each year based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Department, however, has not chosen between the two different indexing methods that it has studied and has solicited comments on the indexing process. The Department also proposes to increase the minimum annual compensation for the highly-compensated employee exemption. The current minimum is $100,000. The

Department proposes to increase that figure to $122,148 a year for 2016, and that this figure be increased annually based on the same index that would apply to the weekly salary requirement.

No Change to Duties Test

Many commentators had also predicted that the Department would propose changes to the so-called “duties test” for the executive, administrative, and professional exemptions, including the adoption of a California-style requirement that 50 percent of an exempt employee’s time each week be devoted to performing exempt tasks. In an interesting turn of events, the

Department has solicited comments regarding the respective duties tests but has not proposed any specific regulatory changes at this time. It remains to be seen what the Department will do as to the duties tests. By choosing not to include any proposed amendments regarding the duties tests in the Notice, the Department may have foreclosed its ability to make regulatory changes

39

3822795v.1 without further notice and comment. On the other hand, the solicitation for comments may indicate that the Department is considering issuing a second round of proposed amendments, and opening up a second comment period, at a more opportune time in the future.

What Happens Next?

For now, these are just proposed changes to the regulations. The DOL is expected to issue final regulations in mid-2016. The regulations have not changed, and employers are not required to take any action at this time. However, it is not too early for employers to begin their planning on how to comply with this new rule with respect to exempt employees whose salary currently is less than the expected new salary threshold.

E. Department of Labor Cracks Down on Independent Contractors

On July 15, 2015, Wage Hour Administrator David Weil issued Interpretive Guidance on the misclassification of employees as independent contractors. As employers probably expected, the U.S. Department of Labor takes the position that most workers are “employees” and not

“independent contractors.” The DOL has stated in support of its policy that “when employers improperly classify employees as independent contractors, the employees may not receive important workplace protections such as the minimum wage, overtime compensation, unemployment insurance, and workers’ compensation. . . . [S]ome employees may be intentionally misclassified as a means to cut costs and avoid compliance with labor laws.”