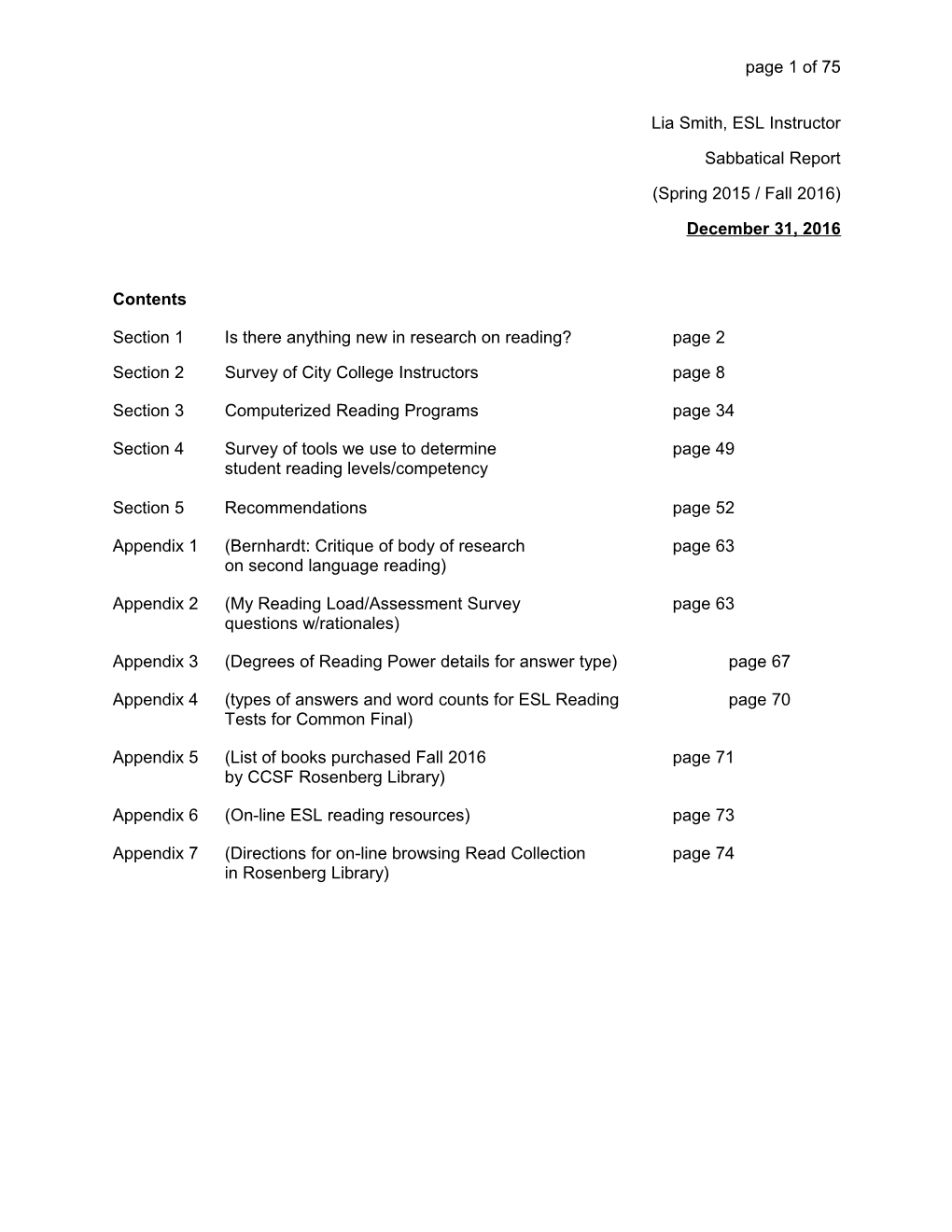

page 1 of 75

Lia Smith, ESL Instructor

Sabbatical Report

(Spring 2015 / Fall 2016)

December 31, 2016

Contents

Section 1 Is there anything new in research on reading? page 2

Section 2 Survey of City College Instructors page 8

Section 3 Computerized Reading Programs page 34

Section 4 Survey of tools we use to determine page 49 student reading levels/competency

Section 5 Recommendations page 52

Appendix 1 (Bernhardt: Critique of body of research page 63 on second language reading)

Appendix 2 (My Reading Load/Assessment Survey page 63 questions w/rationales)

Appendix 3 (Degrees of Reading Power details for answer type) page 67

Appendix 4 (types of answers and word counts for ESL Reading page 70 Tests for Common Final)

Appendix 5 (List of books purchased Fall 2016 page 71 by CCSF Rosenberg Library)

Appendix 6 (On-line ESL reading resources) page 73

Appendix 7 (Directions for on-line browsing Read Collection page 74 in Rosenberg Library) page 2 of 75

This report is organized in sections. Section 1 introduces the idea that there is no “general reading skill,” and presents what might be reasonable expectations for how well a literate, educated second language reader might be expected to handle advanced disciplinary texts. Section 2 contains the results of my survey “My Course Reading Load / Assessment” done here at City College of San Francisco (CCSF). Two hundred and thirty instructors across the disciplines participated and wrote voluminous comments, revealing that they are deeply engaged with their students, are doing superlative work, and support student reading. Four themes emerged: reading loads are significant; completion and comprehension of reading assignments are inextricably tied to success in courses; prior knowledge supports reading; instructors change reading loads as they evolve as teachers.

In Section 3, I describe and analyze two computerized reading improvement programs, Degrees of Reading Power, and Reading Plus, both used at City College. My research and analyses show that the creators of these programs have not drawn sufficiently from reading experts, that they have built their programs on the questionable notion that there is a general reading skill, and that the programs themselves may be requiring time that students might better use to read and/or receive support for comprehending course assignments.

Section 4 is a survey of tools used at City College to determine student reading levels/competency. In this Section, I include information from my survey literature on reading in a second language.

In section 5, I make recommendations.

Section 1

Is there anything new in research on reading?

Students in general, and ESL students in particular, struggle with reading but it is a fact of college study that instructors across the disciplines (science, technology, engineering, math, art, communications, etc.) use text to transmit information. Students who are poor readers, or are perceived as poor readers, may find it difficult to succeed in their college courses. When trying to find solutions to help struggling students, instructors may complain that students lack preparedness. If a student’s first language is not English, the English department may fault the ESL department: “Your job is to teach them the English.” Similarly, when faced with students who seem to be poor readers, content instructors may fault the English department: “Your job is to teach them to read.”

The assumptions behind both these charges are misguided. Although second language learners can gain a certain level of mastery over English in advanced ESL courses, there is no “body” of English that students can master before attempting content courses (e.g., Asian American Studies, Computer Science, Economics). Second language research shows that second language readers may comprehend at higher levels than tests necessarily show and, with explicit instruction, can learn to use their first language reading skills to good effect. Reading researchers also suggest that there is no such thing as a general reading skill, and that all readers must be explicitly taught to read advanced disciplinary texts.

Second language readers page 3 of 75

What is called the Compensatory Model of Reading is a helpful framework to discuss reasonable expectations for second language (L2) readers. In the Compensatory theory, skill in second-language reading breaks down as follows (Bernhardt, 2011):

i. Literacy in L1 accounts for 20%

ii. Language knowledge for 30% (grammar + vocabulary, L1/L2 distance, etc.)

iii. Other 50% unknown This means that it is supposed that a student literate in her first language can be predictably trained to a reading competency of 50% in another language. After that, what helps a second language reader develop her reading skills is unknown. To get at this mystery, one place researchers have looked is vocabulary. And, indeed, research in both first language (L1) and second language reading (L2) soundly proves that building vocabulary helps students advance in reading skills.

Since the 1940s, it has been maintained that for a reader to understand a text, she must know 95% of the words. Corpus linguistic studies have helped researchers determine that up to 50% of the words found in English texts are high frequency words, the body of which is sometimes cited as numbering 2,000 for reading of general texts, and up to perhaps 2,570, when an Academic Word List, providing “a coverage of about 90% in academic texts,” is added (Cobb, 2009). To illustrate, the word “the” accounts for 6-7% of the words in any given English text. Knowledge of this single function word moves a reader from 0% comprehension in English to 6%. In an academic discipline, such as science, direct instruction could potentially help students acquire and potentially master the vocabulary on an Academic Word List created for that domain, adding further coverage. It might seem that what are called “the first 2,000 words” can be learned in a systematic and predictable way by an average language learner; however, studies have shown that ESL students with upwards of 4,800 known words in English, typically know only about half of the 2,000 most frequent word families (ibid, p. 150-151). Experience indicates that ESL students will not “naturally” learn the first 2,000 words simply by reading available materials or reading according to interest. Promisingly, second language reading researchers and the experience of classroom instructors suggest that it’s possible to bring a literate, educated ESL student up to an 80% comprehension level in a relatively short period of time—several years of intensive, immersion study— through direct vocabulary instruction.

However, every gain in comprehension after that is very slow and quite incremental. In order to increase her vocabulary, a reader must be repeatedly exposed to an unknown word. If one assumes she can do this by reading new texts that are at her level, the fly in the ointment is that corpus studies show that the percentage of different words “that turned up only once” in authentic texts is approximately 54% (Adams, 2009). For learning new words, “the overall determination seems to be that at minimum, ten occurrences [of a new vocabulary item] are needed in most cases just to establish a basic representation in memory” (Cobb citing Horst, 2009). That is, if the foregoing is true, reading a text containing unknown words will not automatically expose a reader to new word items often enough for her to learn them.

The points above strongly suggest there are no obvious shortcuts for a second language reader to acquire the vocabulary it takes a native speaker twenty years to learn,

In fact, there is no manner to teach an ESL learner “the English” in an ESL program to prepare her for reading advanced disciplinary texts in content courses. In the U.S., it’s been estimated that an 8th grader must know 600,000 words to do well in school and that, through direct page 4 of 75 instruction, this same 8th grader might gain approximately 8,640 words over the course of 12 years. To address this confounding mismatch, what first language reading researchers have proposed is that average and ordinary readers build vocabulary through extensive, independent reading (Adams, 2009). With vocabulary gains for foreign language students studying abroad (in the target language environment) similarly estimated at 550 per year (Milton & Meara, 1995), it seems unreasonable to expect a college-age student whose native tongue is not English to learn, or be taught, “the English” before she enters a mainstream English class or begins taking general education courses. Indeed, like the native speaker, to make necessary vocabulary gains for academic success, a second language reader must read, a lot, and have access to materials that are at 95-98% her reading level. It’s important to note that the kinds of texts that would help both an ESL student who struggles with reading to achieve automaticity (able to ready fluently) and an ESL student who competently reads with 80% mastery to increase vocabulary through independent reading, are in short supply. We also need to keep in mind that, were materials for both struggling and masterful second language readers to be in full supply (materials that are at 95-98% difficulty and on subjects and topics pertinent to the student’s area of study and/or interests), adult second language learners don’t often have the kind of free time required to read the amount of material that would translate into rapid vocabulary gain. For the second language reader, the barriers between what can be learned and what must be learned are far more numerous than for the first language 8th grader.

All readers

Setting aside the issues of “Vocabulary” and availability of texts for a moment, the second idea, long held, that there is a “general reading skill” that can be taught in an English class and used on all manner of texts, is appearing to be wishful thinking, for two reasons. First, readers need to be trained to handle lexical density to read advanced disciplinary texts. The kind of reading one does in elementary school is very different from what is soon required for academic success as schooling proceeds. We begin reading largely by reading narrative texts. These texts can be vocabulary demanding (and for second language readers, demanding because of cultural referents and a preponderance of idiomatic language), but are typically not lexically demanding, even when written for adults. According to Halliday and Martin (1993), everyday spoken language has a lexical density of 2 and 3 compared to written texts at an index of 4 to 6, with science texts going up to 10 or higher. Moving from comprehending texts read in elementary school to texts in middle and high schools, and college, does not happen automatically. Responding to statistics from the Nations Report Card: Reading 2005, which showed that “strong early reading skills do not automatically develop into more complex skills that enable students to deal with the specialized and sophisticated reading of literature, science, history and mathematics,” Timothy and Cynthia Shanahan worked with experts in several disciplines (history, science, mathematics) and concluded, “Most students need explicit teaching of sophisticated genres, specialized language conventions, disciplinary norms of precision and accuracy, and higher level interpretive processes.”

Further, from discipline to discipline, texts are not read in the same manner. In 2001, Len Unsworth at the University of New England, Australia, proposed, “…there is a need to delineate ‘curriculum literacies,’ specifying the interface between a specific curriculum and its literacies rather than imagining there is a singular literacy that could be spread homogenously across the curriculum” (Unsworth, 2001), and the work of the Shanahans and others supports this idea. Through direct work with content experts in math, chemistry, history, and literature, the Shanahans learned that disciplinary experts read texts in their respective fields quite differently (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). page 5 of 75

Reading the work of Zhihui Fang (2012) gave me some of the “how” of what Shanahan and Shanahan outlined in 2008. Although the Shanahans focused their studies on adolescents, much of what they’ve uncovered has strong implications for community college instructors. Certainly, if a college instructor views herself as a mentor to her student apprentices, it follows that she will work to find ways to explicitly teach her students some of the building blocks they will need to approach and read the texts from her discipline in the same manner she does.

In his paper, The Challenges of Reading Disciplinary Text, Zhihui Fang provides analyses of secondary schooling texts from science, math and history. In order to show the leap that elementary school readers must make when they begin reading secondary education texts, he describes these texts according to how certain grammatical features of English are exploited to convey complex and advanced thought.

Fang explains that in science texts, readers are faced with technical vocabulary, long noun phrases, nominalizations, and metaphorical realizations of logical reasoning. For math, a reader must grapple with technical vocabulary, semi-technical terms, long noun phrases, symbolism and visual display. And, history texts are full of generic nouns, nominalizations, and abstractions that suggest causality. To approach a history textbook critically, a reader must be able to do several things, including being able to discern how a writer sandwiches a fact or set of facts between his own prediction and conclusion, which Fang calls “texture.”

Historical discourse…is often constructed in abstract language that infuses the historian’s ideological perspectives. The abstraction is realized through 1) the use of… generic nouns…2) nominalizations, which turn a series of events, an action, or time sequences into “things”…3) evaluative vocabulary to indicate affect, judgment and valuation…4) texture…5) within-clause realizations of causal relations that sometimes conflate causality and temporality (Fang, 61-63).

Fang’s work seems to clarify some of the difficulties that second language readers face when accessing advanced texts in high school and college. “The difficulties of disciplinary texts lie not just in vocabulary, but more broadly in the discourse grammar, or language patterns… [and these features serve] quite different functions across the subjects” (ibid, 63). To illustrate, Fang enumerates the following uses of nominalization:

In science, nominalization helps accumulate meanings so that a technical term can be defined or an explanation sequence synthesized for further discussion.

In history, nominalization is often used to portray events as things so that historians can develop a chain of reasoning that simultaneously embeds judgment and interpretation.

In mathematics, nominalization helps create semitechnical terms that are then quantified, reified as mathematical concepts, or put into new relationships with other concepts. Especially in a college environment, where it is not uncommon for English instructors to coax students away from over-use of nominalization in their writing, teaching students how nominalization is used effectively in advanced disciplinary texts is an important key to helping students improve their reading comprehension.

Limits of transfer of first language (L1) reading skills to second language (L2) reading page 6 of 75

Second language reading research strongly shows that L1 literacy has a markedly positive bearing on how well someone learns to read in a second language. Just as poor L1 readers tend to become worse readers as they advance in their schooling and good L1 readers tend to become better readers over time (keeping in mind that learning to read advanced disciplinary texts must be explicitly taught), good readers in L1 have superior advantages over poor readers in L1 in gaining high literacy in a second language. However, the assumption that a literate subject can transfer her reading skills in her first language (L1) to a second language (L2) has been largely based on the idea that there is some set of measurable “universal reading skills” that readers can employ across languages. This theory has not been proven and, according to Bernhardt, studies to date have been deeply flawed (see Appendix 1). I have already mentioned that there is a growing body of evidence that there is no such thing as “a universal reading skillset,” or even what could be called a “general reading ability” that can be used with any and all texts in a reader’s L1. Another wrong assumption is that just as a bi-lingual speaker of English and French changes her “code” when she leaves San Francisco (stops speaking English) and enters Paris (starts speaking French) this same individual will “turn off” her English when she reads French. On the contrary, both brain research on reading processes and L2 reading research show that the first language is always present and, paradoxically, can provide both interference and assistance.

As a means of organizing this discussion, I will use the hypothetical model Barbara Birch (2002) proposed in her book, English L2 reading: Getting to the bottom. She suggests that L2 reading has two parallel processing components:

Processing Strategies Knowledge Base

Cognitive Processing Strategies World Knowledge inference people predicting places problem solving events constructing meaning activities

Learning Processing Strategies Language Knowledge chunking into phrases sentences accessing word meaning phrases word identification words letter recognition letters sounds

page 7 of 75

I will start with the two bottom components, which are essential for reading. (The top two are necessary but not essential). First, looking at “Language Knowledge” a reader must be able to hear and differentiate sounds. This is the basis of spoken language, which humans began to write down when they invented writing. (This is not at all to say that deaf people cannot learn to read, but that is another discussion.) If the written language is alphabetic, the reader must next be able to determine what a letter is, and this must be taught. If you are unfamiliar with Arabic script, you might think that text is one continuous line. Untrained eyes (or untrained readers of Braille) cannot tell where one letter leaves off the next begins. Readers must be able to tell the boundaries of letters, of words, of phrases and of sentences. At all of these junctures, L1 can interfere with or slow down L2 processing. For a reader of Chinese, a logographic language, where native speakers memorize characters as part of learning to read, trying to use the same “accessing word meaning” strategy—memorization—to learn to read in English impedes progress; since English uses an alphabetic script, as long as a reader is mastering a foundation of “sight” words (words that must be memorized), it is far more efficient to read by sound. As a reader of English, when moving to Pinyin, a representation of modern Chinese using the Roman alphabet, when I read “qin” in Pinyin, to process the Chinese word, my English reading brain has to ignore the excitability of the letter ‘q’. That is, I can be slowed down as my English reading brain notes that the expected ‘u + vowel’ is not there (quick; brusque; quadrant), or when my brain miscues meaning because the pronunciation of “qin” is associated in my mind with the English word chin— [亲切 ( qīnqiè = cordial]. What about cognates? Do they help or hinder? Studies have shown that although cognates (words that are similar or the same from one language to another) can be helpful for an English speaker learning Spanish, false cognates (embarazada in Spanish means pregnant) and cognates that are limited to a single meaning (conveniente in Spanish is typically any cost/benefit advantage where convenient in English is most often related to location) mislead, and the promise of cognates limits some learners from acquiring vocabulary. “Well, in English, it’s ordinary and in Spanish, it is ordinario, so I’ll just add “o” to every word and I’ll be speaking Spanish.” If the reader reads from right to left in her L1, as in Arabic and Hebrew, adjustments have to be made to process letters with the opposite sweep. Syntactical differences can also slow down reading. In Japanese, the verb comes at the end of sentences. So, a native speaker of English will have to make this adjustment with her reading if she constructs meaning through subject verb pairs appearing at the beginning of sentences. All of these “interferences” are extremely slight, many happening in milliseconds or faster, but nevertheless can slow down reading and/or add to reader fatigue in L2.

Moving to the other two components, which “are necessary but not sufficient for competent reading” (Lems, 2010), L1 can also interfere with or slow down processing. For example, in Chinese, concession often comes at the end of a sentence, or paragraph, or even the entire text. This is quite different from texts typically read in American schools where the concession comes at the beginning of a sentence, paragraph, or the entire text. As long as these differences in how texts are organized are pointed out, mastery over L2 reading can proceed smoothly.

More problematic, however, is the final category: World Knowledge. Incomplete or a lack of world knowledge can lead readers astray. “[My student had read a passage in German and] answered all my content questions about the passage accurately… [and then remarked] that she didn’t know Martin Luther King, Jr. knew German” (Bernhardt, p. 103). If the student had been aware of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, might she have comprehended the passage more fully? World knowledge encompasses more than just historical facts; it also includes educational development. “… [We] memorized everything…and then reproduced what the teacher knew. That was what was considered literacy—being able to read and write what the teacher knew…. page 8 of 75

[It wasn’t until we reached higher levels of education] that we began to understand that literacy…was understanding what is around us” (Ball quoting Gafumbe, 2006). Mieko, an Asian American, reported not reading from junior high school through her first years of university. It wasn’t until she was assigned to keep a reading journal that she was “forced to think about the material…rather than simply absorb it, perhaps to be forgotten later” (Ball, 2006, p. 89). That is, we learn facts about the world—Martin Luther brought about reform in Germany in the 1500s; Martin Luther King, Jr. brought about reform in the United States in the 1950s— and we also grow as learners and thinkers, depending on where and how we are educated. If we are taught to memorize everything we read, we will be very different readers from those who are taught to consider any number of subtexts, for example the biases a writer brings to her writing.

Research studies (albeit imperfect) show that L2 readers sometimes use L1 reading strategies and world knowledge when reading in L2, but not always. One theory is that language learners will only start to use L1 reading strategies once they gain proficiency over L2, but researchers have not been able to discern any rhyme or reasons for when, and why L2 readers use L1 reading strategies and their world knowledge.

Are we using the best reading materials to teach language?

Historically, it has been assumed that a reader accesses language through the reading of literary texts. To this day, despite trends towards using communicative language methodology, upper level foreign language students largely study “classical” literature of the target language. There have been many reasons for this, least of which was the availability of texts. For example, it has been fairly easy for a K-12 teacher in the U.S. to get an inexpensive class set of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, or for an ESL instructor at CCSF to determine that a young adult fiction title will be accessible by his/her students.

However, despite the low cost of this approach, educators have found that using “classical” texts is problematic. In the United States, for example, so-called “classics” are often irrelevant to the lives of diverse students who come from a multitude of language and ethnic-origin backgrounds. Literary “classics” can also be narrow in focus. For example, in a lively discussion of vocabulary acquisition, Marlise Horst of Concordia University in Montreal points out that readers will easily learn the word “moor” if they should read an abridged version of Wuthering Heights (p. 46-47, Horst, Section 2 in Han & Anderson, 2009). However, the noun moor is not on any Academic Word list and is not in the word families that comprise 80% of the vocabulary one needs to read English with some ease. Finally, literary “classics” are often taught so that students comprehend the text “…at a literal level…and appreciate [the piece] as a work of literature…situated in a particular historical time frame” when what students need are opportunities to “…openly critique [a text] by comparing it to other classic and contemporary texts…to question [the themes, such as injustice], and to produce media” (Hicks & Steffel, 2012).

Still, finding a properly leveled set of non-fiction texts, without copyright restrictions, on current affairs is very difficult. The advent of the Internet brings a potential for change, and language educators have been considering and experimenting with using non-literary texts to help move students towards being able to handle “upper register texts.”

Section 2 – Survey of City College Instructors

I wanted to find out how much reading CCSF instructors were assigning, and survey the types of reading support they offered as well as the assessments they used to determine whether page 9 of 75 students were successfully completing reading assignments. My assumption was that a number of students were possibly being assigned more reading than they could handle and/or were not, for any number of reasons, completing reading assignments. I also suspected that reading loads had increased because of technology.

Part of my interest in this direction of inquiry came from a student-produced video, “Reading Between the Lives,” produced in 2009, by a group of Chabot Community College students. In this video documentary, recently posted on YouTube in 2015, students relate their experiences regarding “reading.” Tellingly, one states that he only buys the textbook if he judges his instructor to be a poor lecturer. The students in the video seem to understand text responsibility, and state that pragmatics, for the most part, determine how much and what kind of reading they do (Chabot, 2009).

Through my survey, I hoped to find out how the instructional practices of instructors here at City College of San Francisco, also a community college, might be encouraging or dissuading students from reading.

Please note that a somewhat similar survey was conducted at CCSF in the spring of 2013 by a Basic Skills Committee (Andrew King, Lisa King, Tore Langmo, Linda Legaspi, Caroline Minkowski, Cindy Slates, and Elizabeth Zarubin). This group wanted to investigate what CCSF instructors were doing to engage students with text. Ninety-seven instructors across twenty-one disciplines participated in the 2013 survey with the highest number of participants in ESL (21), and the next highest in English (9) and Biological Sciences (9). The project was put on hold when Basic Skills changed direction at the college, and no report was generated.

Overall, my survey revealed four main themes: that reading loads are significant, that completion and comprehension of reading assignments are inextricably tied to success in courses, that prior knowledge supports reading, and that instructors change reading loads as they evolve as teachers.

Reading Loads

Surveyed instructors are typically assigning at least 2 hours of reading per week, meaning that it’s possible that students who carry a full load (3-4 classes) carry a 6-8 hour load per week. One instructor did mention considering how the reading load might affect a student’s overall study time. “Many students have two to three classes with me per semester, so I try to manage their time… they will also have a written assignment with the reading” (#209, Health Care Technology). Instructors may be underestimating the time it takes students to complete reading assignments, particularly for ESL students, who tend to spend 3-4 more times on reading assignments than native speakers of English. A conservative estimate of the hours needed for reading class texts for an average full-time ESL student may be upwards of 20 hours per week.

Elizabeth Barre, Assistant Director for the Center for Teaching Excellence at Rice University, recently created an on-line workload estimator to help college instructors understand the factors to take into consideration when assigning reading. These factors include the number of words per page (typically 750 per page in a college textbook), the difficulty (no new concepts, some new concepts, many new concepts), and the purpose of the reading (survey, understanding, engagement). For the calculator, see: [http://cte.rice.edu/blogarchive/2016/07/11/workload]. page 10 of 75

Ancillary Reading Adds to Reading Loads In the survey, ancillary reading was defined in the question prompt to mean syllabus, assignment sheets, handouts, peer review, instructions for using Insight and other computer applications, Internet forums, etc. Due to the flawed survey question, instructors gave a variety of definitions about what constituted “ancillary reading,” and it was unclear from the data whether instructors considered ancillary reading part of the reading load. For example, a few instructors interpreted “ancillary” to mean optional independent reading.

Instructors reported assigning the following ancillary readings:

peer review

instructions

class handouts (some instructors go over these during class)

on-line resources (optional)

support resources (optional)

ad hoc newspaper articles (current events)

lab assignment

English and ESL instructors report providing the largest number of handouts and detailed assignment instructions. Instructors might consider how much ancillary reading adds to reading loads.

Direct Reading Instruction Question 10 asked instructors what direct instruction they gave their students during class to help them complete their reading assignments. Impressively, responses show instructors work hard to engage students in reading but, more importantly, responses show overwhelmingly that assigned readings serve to help students master course material. Most encouraging, in light of current research being done on reading was that 42% of respondents report that they instruct students to read texts “in the manner that reading in my discipline requires.” Cynthia and Timothy Shanahan, joined by other recognized experts in reading research, have questioned the idea of a “general reading skill” and argue that students must be explicitly trained by experts in a specific discipline to read advanced disciplinary texts in that particular discipline. In The Challenges of Reading Disciplinary Texts, Zhihui Fang quotes Michael Came, a math teacher, describing how he teaches his students to read word problems:

I summarize the goal of the problem and determine what is being asked before I do anything else…The goal of this particular problem is to find out the total area of the top surface of five round stools. The word round implies that the surface is a circle…I know that thinking about circles can involve many different concepts such as radius, diameter, and circumference…I also know that the formula for the area of a circle is A = π r2…So, now I know that I need the radius to find the area. Other page 11 of 75

formulas might be useful in case the radius isn’t given. These formulas are C = πd and d = 2r…. I also get rid of information that is not important by crossing it out… [127 words excerpted from 400+] (Fang, 2012). One surveyed CCSF math instructor stated, “I try to model careful reading of word problems and critical thinking when I solve problems for the class at the board” (#8, Math), an example that there is awareness that content instructors must explicitly teach students how to read according to the target discipline. Respondents also reported discussing genre and purpose with their students. Familiarity with genre is a good predictor of whether a reader will comprehend a text well enough to pass a standardized reading comprehension test, and reading for a purpose can guide readers to focus their reading. Considering genre is a method for activating prior knowledge, and identifying purpose is a method for determining importance. Both activating prior knowledge and determining importance are highly effective reading strategies.

Reading Comprehension Tied to Prior Knowledge The theme of reading being tied to prior knowledge came up in the question about reading assessments. A good number of CCSF instructors use assessments of their students’ reading comprehension to guide students to learning resources and generally support student learning. Notably, however, the majority of surveyed math instructors commented that without reading comprehension, a student would be unable to complete the coursework. “Reading comprehension is not explicitly part of my students' grades. Nevertheless, they must comprehend word problems in order to solve them correctly” (#8, Math). This need for reading comprehension was echoed by several instructors in other disciplines. “Their comprehension does affect their grade, in that their ability to succeed at the essay task is influenced by their reading comprehension” (#58, English). “Mostly in capstone project students are assessed on how thoroughly they have accomplished research and topics” (#136, Environmental Horticulture & Floristry). “I don't have a category for reading comprehension in the grade breakdown, but one can't pass an English class if the readings are not understood” (#199, English). “Reading is needed to complete in-class work, presentations, and papers” (#203, Child Development).

Conversely, in some courses, instructors state that prior knowledge or general competence is more important than unassessed reading comprehension. “Exams assess reading comprehension [of each student]. However, it is difficult to say whether the grade reflects their reading comprehension, or lecture comprehension, or their previous science knowledge. With science courses, their reading comprehension is highly affected by their previous course work!” (#86, Biological Sciences). “If they grasp the ideas in a classroom, college and in employment, then I am not too concerned with reading comprehension” (#174 Library Information Technology). These astute comments are directly tied to current reading research that shows how deeply knowledge influences reading. “Words are not just words. They are the nexus—the interface— between communication and thought” (Adams, 2009). To give an example, it is much easier for a cook who has worked in a kitchen for a number of years to understand an advanced text on how to prepare a dish, even if it contains words or grammatical and text structures she has never seen before, than for a lay person to comprehend the same text. The cook has the knowledge to interpret the text, whereas the lay person cannot visualize what the text expresses and so cannot “fill in the blanks” when she encounters unknown words or sentences with multiple clauses. page 12 of 75

Changes in Reading Loads Over the Past Ten Years The question of whether instructors had changed their reading loads in the last ten years, by far, elicited the most information in terms of what is required to use college reading as an effective teaching tool. One of my unstated hypotheses was that reading loads have increased, particularly ancillary loads, due to technology. The survey doesn’t show this, but the comments do. Any instructor who adds an on-line forum to her class (e.g. Insight or Canvas) has increased the reading load. Curiously, some instructors don’t consider computer use as reading. In an extreme example, one instructor commented that reading loads were not applicable since the course was offered on-line. I was also surprised that a Library Information Technology instructor did not see advanced reading skills as a must for successful completion his/her course work. Certain comments made me wonder if computer use has become so ubiquitous as to go unnoticed as a reading activity. Even if one appears only to be using a computer for accessing videos and other visual media, some reading is still required.

Factors Affecting Reading Loads

Although one instructor offered, “My [weekly] guideline has always been 30-50 pages for lower division undergrad, 100-200 pages for upper division, and 200-500 pages at the grad level” (#93, Political Science), it’s important to consider that while City College’s college curriculum committee always checks that a credit course assigns enough homework for the Carnegie units, including the reading load, this design (often far removed from what an instructor does in the classroom) is really the only standardization for how much text an instructor should assign. Some instructors may begin their careers assigning too much reading (unrealistic) or too little (inadequate for students to learn what is required). For the most part, instructors who offered comments revealed that they have matured over time in their teaching practices and how they assign reading loads

Several instructors report that increases in ancillary loads are due to new state requirements. “This is probably due to the fact that instructors are now being required to document so much of what they do in the classroom. The length of my first day handout has doubled!” (#105, ESL). “It is due to the increased amount of paper work that our school is required to complete” (#161, Disabled Students Programs and Services). But, by far, the majority of instructors report having increased reading loads due to the better availability of resources to encourage learning. “I am hoping that smaller or shorter ancillary readings that pertain to students' lives will get them to read more” (#109, ESL).

Indeed, instructors report having made changes to reading loads because they have gained experience and expertise. Experience gives instructors tools to better understand student needs, select reading materials judiciously, and create effective handouts.

One selection instructors make is textbooks, and better books can increase, decrease, or re- balance textbook and ancillary reading loads. “The new textbook includes enough [so I eliminated] ancillary text. Cost factored into this” (#171, Political science). “I got rid of the text… and now assign on-line articles and websites…I've customized many handouts to provide specific information in a simple, concise format. I have found that students learn better if the information is direct, well organized and not over burdening” (#196, Child Development). “I have a better textbook, and so I don't need to use as many handouts” (#200, English). Instructors also comment that they want to protect students from the high cost of textbooks whenever possible. “The main reason for a slight decrease is that I choose shorter, less expensive books” page 13 of 75

(#169, Anthropology). “Text books are outrageously priced…so I provide materials for the students to learn the information if they are not able to purchase the book” (#229, Photography).

Instructors who have increased their reading assignments express excitement about being able to offer more to students. “There is more I want students to learn. I have more resources” (# 5, Culinary Arts). “[I’ve added] more short introductions to readings to help them contextualize the reading, more handouts to check for reading comprehension/analysis” (131, History). “Reading is a great way to learn a language! I have been inspired by my own progress in foreign language, hugely improved through continual, daily reading” (#39, ESL). “I've diversified the sources, to provide a more diverse range of voices and approaches to the material” (#220 Visual Media Design).

Many who have pro-actively reduced the number of reading assignments cite having gained a better ability to focus students. “I have found that students…are more likely to complete the reading if there are fewer assignments, so I have focused on a few specific examples of what I most want them to learn” (#131, History). “Students with weak English were plowing through too much optional material…I decided to focus more on [basic concepts] that confused students” (#156, Economics). “As students have read less or been less able to read (due to time or comprehension), I have reduced the reading load so we can spend significant time on each [text]” (#91, Speech Communication). “Texts have changed… [and] require less work to understand… [I’ve also reduced ancillary reading assignments.] It has been hard enough to get them to read the text” (#113, Child Development). I found students overwhelmed by the reading; they learn more, unencumbered…learning by doing” (#163, Broadcast Electronic Media Arts).

Others have done so purely for pragmatics. “Too many students would fail the class if I required more of them” (#50 Psychology). “I feel that there is pressure from students and other faculty to reduce the out-of-class workload on students” (#134, Broadcast Electronic Media Arts).

Although one English instructor reports having reduced assigned readings due to “curriculum constraints,” all other instructors reporting that they have increased reading loads cite curriculum changes, pedagogical insights, and departmental shifts as reasons. “The course outline now specifically includes reading skills” (#13, Mathematics). “The text reading does not engage the type of learning found in Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive learning” (#78, Biological Sciences). “The English Department standard has shifted [in the last ten years] to include more authentic readings in English 91, and frequently to include a complete book” (#68, English). “Higher expectations from students and teachers” (#101, ESL).

Technological advances have had a great impact on reading loads. While it is true that information remains fairly stable in some fields, technological advances in certain fields and in methods for instructional delivery are significantly adding to reading loads. In Fire Science Technology, for example, patient assessment protocols have not “changed radically” (#205, Fire Science Technology) but “the Student study manual has been updated…for today’s demands in the life safety discussion, [and is more detailed]” (#210, Fire Science Technology). “Due to increased aircraft technical complexity, reading loads have increased. Students are required to obtain more technical information” (#217, Aircraft Maintenance). “Due to the use of newer software for post-production, more handouts and ancillary reading is given to students to give them more current information that the book might not cover” (#229, Photography). “Health care and technology changes happen daily. Textbooks are printed every 3-4 years. To keep the curriculum current, we assign additional reading to make sure students are prepared to enter the current workforce” (#209, Health Care Technology). page 14 of 75

A number of instructors report an increase in reading loads because they have been able to improve instruction by using the Internet. “The Internet makes it possible to research specific cases and we use that” (#166, Broadcast Electronic Media Arts). “Using websites to add online sources is now available” (#74, Biological Sciences). “I found better texts that come with a CD or have a video on YouTube” (#66, ESL). “Since I began using Insight five years ago, I have been assigning more reading” (#23, ESL).

At the same time, technology is also allowing instructors to replace reading assignments. “Most of my students have expressed more interest in required viewings such as TED talks. This change [allows me to respond to] differences in learning styles” (#122, Biological Sciences).

One group of instructors express a certain resignation about the state of reading. “The students don't read; that's the truth” (#7, Culinary Arts). They don't read, and lots of books at the bookstore tell students to stay away. I just can't handle the terrible writing anymore” (#168, Anthropology). “I find that students are increasingly reluctant to read. Many seem capable, but find it boring or old fashioned. They say they don't have time to do the reading or just didn't get to it in time” (#169, Anthropology). “I've found that students are less and less inclined to read lengthy material. I've cut way back on the reading assignments and rely more on in-class instruction” (#196, Child Development).

These comments about reading attitudes somewhat echo the comment of Mark Sadoski, author of Why? The Goals of Teaching Reading (2004), who states, “In fact, aliteracy [can read but don’t] may be one of our most pressing literacy issues because with reading, as with other abilities, its value lies not in its possession but its use.”

A caution for instructors is to remember that they themselves, and not the students, are changing. It is easy for experienced instructors to fall into the fallacy that somehow today’s students are not the same as students in the past. While it is true that “[it is not] sufficient to have motivated readers who read with little skill or read only in a restricted domain such as simple fiction” (Sadoski, 2004), the following comments may reflect the maturation and expanded knowledge base of the instructor more so than the students s/he encounters. “I expect that students who do not understand vocabulary will look things up but students have come to class expecting that they would be told how to connect the dots.” “[There has been a loss in] the ability to recognize abstract terminology & application of metaphor and analogy & [there has been a] lessening of a common cultural language and knowledge.” “Students preparedness for college has definitely declined, and as well, the number of students who seem to have natural ability to succeed in entry level classes has gone down.” Instructors who have these feelings, might consider Alfred Binet’s core belief: Intelligence increases with age. When France made public schooling a right for every child, Binet’s “intelligence test” was designed as a tool to help teachers serve students who came to school with less experience than the youngsters the private schools were habituated to serving. Students who can succeed in entry level classes have sufficient experience to do so.

In the age before the Internet, a high school reading level was considered more than adequate for nearly anyone to succeed in the work world (Adams, 1994; Chall, 1996). Today, because of the technological advances and the Internet, citizens need much higher reading levels. Changes to City College of San Francisco curriculum reflect this. “The writing assignments have become more sophisticated and plentiful in English 91. Students are doing more reading before they begin writing an essay than in the past. All essays are text-based and require using information from multiple sources” (#185, English). Regardless of whether English classes in high schools are preparing students as well as in the past to read literature, a claim that research tends to support, the same research shows that science texts are growing increasingly more difficult and page 15 of 75 that high school textbooks do not necessarily ask for the kind of advanced reading that college students and those in the workforce must do (Adams, 2009). It is reassuring that CCSF instructors are attuned to both the reading demands in their disciplines and the needs of their students, as well as making thoughtful changes to their reading assignments as they evolve in their teaching practices.

Survey Results

All CCSF instructors were invited to participate through list-serves, department chair requests, the EFF and personal request. Non-credit ESL instructors also participated. For the survey questions and rationales, see Appendix 2. Q1. What is your discipline? Two hundred and twenty seven CCSF instructors from forty three out of seventy seven CCSF disciplines (56%) participated, representing a broad range across the college curriculum, and over 15% of the 1,482 total number of faculty. Those who took the survey included instructors from Aircraft Maintenance, Art, Culinary Arts, Fire Science Technology, Mathematics, Photography, and Visual Media Design.

That 40% of respondents represent the English and English as a Second Language departments is not surprising given their large sizes. Despite the small sizes of their departments, instructors of Administration of Science, Biological Sciences, Broadcast Electronic Arts, Child Development, Culinary Arts, Disabled Students Programs & Services, Fire Science Technology, Health Care Technology, Library Information Technology, Nursing – Licensed Vocational, Photography, and Visual Media Design participated at high rates. Art, Foreign languages and Math instructors participated at significant rates, particularly as these disciplines are not viewed as “text” demanding.

Q2. Are you full or part-time? Full time: 158 (70%) Part-time: 69 (30%)

Q3. What division do you teach in?

Credit: 174 (76%) Non-Credit: 31 (14%) Both: 21 (9%) Other: 1 (.4%) This instructor reported on courses taught at another institution.

Q4. Which of the following reading skills do your students need to handle the texts you assign? [graph on following page] page 16 of 75

(Rounded numbers on the right represent number who chose item as “most important.” The percentage is courtesy of Survey Monkey. “Writing an essay” is my error. Please ignore.)

Recalling main ideas 69 (38%) Analyzing ideas in the readings 24 (13%) Summarizing ideas 13 (7%) Using information from the readings to solve problems 27 (15%) Synthesizing ideas drawn from different sources (including non-text sources) 7 (4%) Explaining readings in one’s “own words” 9 (5%) Reading critically and expressing one’s opinions 13 (7%) Writing an essay 13 (7%) page 17 of 75

To interpret the data for this question, it is best to keep in mind that 40% of polled instructors are English or ESL instructors. The fourth choice, Using information from the readings to solve problems, describes the reading students do in math and the sciences. Synthesizing ideas drawn from different sources (including non-text sources) similary describes reading processes for chemistry and math where the reader simultaneously uses descriptive text, symbolism (formulas), and visuals (e.g., graphs or diagrams), in concert to understand concepts.

Q5. Choose one core course to answer questions #6 and #7.

The courses listed for this question were extremely diverse, with very little duplication except in courses offered in multiple sections (e.g., English 95, English 96, ESL 150, ESL 160). This perhaps reflects the diversity among the faculty who took the survey. This could also partly be a reflection of specialization in certain fields (e.g., Fire Science Technology; Visual Media Design) where a particular instructor regularly teaches a particular course.

Q6. How many pages of core reading do you typically assign your students per semester for the selected course? How many words per page, on average?

The number of pages students are assigned per week was evenly spread across respondents with 26.8% assigning less than five pages per week, 24.4% assigning five to ten pages, 26.2% assigning ten to twenty pages, and 22.6% assigning more than twenty pages a week. page 18 of 75

These numbers are reflective of the discipline (e.g., less in Chemistry, more in Anthropology; low number of assigned pages for non-credit, high number of assigned pages in credit).

For the most part, the “less than five pages” per week is reflective of the instructors who teach non-credit ESL. English, ESL credit, and credit instructors fall into the 10-20 and more than 20 pages per week categories. Overall, instructors had only general ideas or none about the number of words per page of the reading texts they assigned. Some remarked that they had never given it much thought. Most gave general estimates for the number of pages they assigned. Instructors of General Education classes (e.g., Nutrition 12) assign 20-30 pages per week, so a student with a full load might have up to 150 assigned pages of reading per week.

Science instructors stated they used texts that contain lots of pictures and graphs. This does not necessarily lighten the reading load but may instead require more time as students grapple to understand concepts through the integration of information from text, symbolism, and visuals. One instructor noted that students with previous science backgrounds might spend less time (1-2 hours) on assigned readings than students new to the discipline. “Others can spend 4-5 hours and would have to re-read the chapters again!” (#86, Biological Sciences).

Math instructors emphasized that being able to comprehend word problems was critical. “… Reading comprehension in word problems is EXTREMELY important, so I feel a need to respond to this survey” (#12, Math). Although the text itself may not be lengthy, students may need to read the passage repeatedly in order to understand both what is being asked and how to go about finding the solution to the problem.

Some instructors noted that they assumed students only skimmed. “I don’t think they read in any great depth.” Others reported voicing expectations to students, with a number of instructors reporting that they expect students to spend up to six hours per week preparing for each class meeting. A Culinary Arts instructor advised students to read the “notes/summary/examples to get the main ideas, then if time allows, read entire chapter” (#2, Culinary Arts / Hospitality).

Q7. How many hours per week do you estimate it takes students to read these core reading assignments? page 19 of 75

Instructors estimate it takes their students two hours a week to complete the reading assignments, with 18.5% reporting less than 1 hour and 7% reporting more than five hours per week. Several instructors mentioned using the Carnegie unit—a minimum of two hours of out-of-class work for each class unit. And, for accelerated class, instructors stated reading loads were doubled.

Responses show that instructors are aware that factors such as level of education, or whether one is a native speaker of English, affect how much time students need to complete reading assignments. “[Four to five hours] for an average student who has completed a non-remedial based high-school education. About 1/3 of my students have Baccalaureate degrees already, so possibly less for them. And I also have many students from under-served populations who may find the reading takes them more than 5 hours per week for full comprehension” (#92, Broadcast Electronic Media Arts). “I think reading, understanding and synthesizing can be done in 1-2 hours per week but non-native English students often struggle with readings. They often translate into their language and then translate back, a strategy which doesn't work well for common usage words that have a different meaning in our discipline” (#190, Library Information Technology). “Reading assignments includes annotating, outlining, or summarizing - This could take 4-5 hours [compared to 2-3] if student are not strong readers” (#110, ESL).

Generally, ESL instructors gave higher estimates for reading time, 4-5 hours a week compared to the 1-2 hour estimates given by content instructors.

Responses also show that content instructors are aware of the type of reading required by their disciplines. “Reading a biology text (studying it) is slow work. Notes need to be taken, vocabulary retained…I [also] assign Connect [I couldn’t find out what this is], almost an hour per chapter, to encourage reading of the chapter” (#80, Biological Sciences). “To read the chapters doesn't take much time. However, to solve homework problems takes a long time. The book is useful as a reference for solving problems” (#124 Physics). “Besides reading, the student is required to remember the reading content and to apply the medical concepts during hands on practice session with manikins” (#205, Fire Science Technology). “In Econ there are frequently graphs or math problems in the text related to the reading. If they read slowly and carefully, which they should do, [a single reading] will take longer, from 1-2 hours. They could skim and just read the text, ignoring the graphs and examples, in under an hour” (#156, Economics). page 20 of 75

Q8. How many hours of ancillary reading do you require students to complete? (syllabus, assignment sheets, handouts, peer review, instructions for using Insight and other computer applications, Internet forums, etc.)

Ancillary reading loads were largely either less than an hour (44%) or 1-2 hours per week (39%). 21 instructors (13%) assigned 2-3 hours of ancillary reading per week. Q9. How are reading assignments distributed across the semester?

About the same number of pages per week 64 (38%) page 21 of 75

Some weeks, the number of pages is heavier… depending on other 75 (45%) assignments (writing/research/presentation/preparing for a test/etc.) The reading load is heaviest at the beginning of the semester 9 (5%) The reading load is heaviest as we approach midterm. 1 (6%) The reading load is heavy in the weeks leading up to a writing assignment 6 (3.6%) and this happens ______a semester. (Use comment box.) The reading load is heaviest towards the end of the semester. 6 (3.6%) other (Please use comment box.) 6 (3.6%)

Responses to this question show that the majority of instructors either assign regularly spaced readings or assign reading loads according to activity.

Most instructors have a clear idea of how reading assignments are distributed across the semester. In English classes, when students are reading full-length works, the same number of pages is assigned each week. ESL instructors report that texts don’t change in length, but the difficulty of concepts, and the difficulty of vocabulary steadily increase. Instructors across the disciplines remark that the reading difficulty increases as the semester unfolds. “[Through reading] the student is required to build on previous concepts of the course…[this] supports the student learning outcome for the course of effective patient assessment for both medical and injury related issues” (#205, Fire Science Technology). One instructor reported making sure to balance reading loads with other assignments.

Instructor comments predominantly show that reading assignments help students meet course objectives. “We start a unit with an inductive opener, which is not text-based, but soon after that we move into a heavy reading period as we are digesting new ideas” (#58, English). “[Reading load increases whenever] I choose to bring in additional information on the topic or provide further explanation of how to perform or understand a particular technique” (#156, Economics).

In some cases, assigned readings decrease as students work on semester projects. “Reading is front-loaded, and tapers off as we focus more on project-based activities” (#220, Visual Media Design). Some semester projects increase reading loads. “Students have a capstone project that requires additional reading for research” (#136, Environmental Horticulture and Floristry). “Reading is typically heavier in weeks between writing assignments. Towards the end of the semester textbook reading is reduced to a minimum but, hopefully, is compensated by students researching their topics of interest” (#166, Broadcast Electronic Media Arts). Q10. During class what direct instruction do you give your students to help them complete their reading assignments? (Check all that apply.) page 22 of 75

a. I specifically teach them how to read texts according to the manner that reading in my discipline requires. (42%)

b. I explain the genre of the reading and spend class time giving explicit instruction for approaching the text. (38%)

c. I instruct them to consider the genre and/or the purpose of the reading before they begin reading. (40%)

d. We do a close reading of each text. (21%)

e. I set aside class time for think-alouds (28%)

f. I interpret the text for the students. (36%)

g. I hold a class discussion about the students’ reading habits. (24%)

h. How a student approaches reading the texts is up to the individual student. (33%)

i. Other: (19%)

Fifty-seven instructors, across the disciplines, added detailed comments for this question, showing a deep involvement in student learning, and described how they specifically teach students to use and hone reading skills as tools for gaining knowledge.

Two instructors begin their courses with an emphasis on reading skills. “I put a long, specific section in the syllabus about how to do the reading and use the textbook…. [and] talk about taking the time to read through explanations of graphs” (#156, Economics). “I start every semester with a lesson in critical, active reading and support it throughout the semester” (#76, Biological Sciences). page 23 of 75

English and ESL instructors reported offering on-going, in-class direct instruction on the use of “reading strategies,” as well as facilitating pair, group, and whole class discussions. Some instructors use student generated questions for discussions, while other instructors invite students to ask questions during class. A number of instructors report that they regularly check comprehension through various means (e.g., requiring students to annotate; analyzing quotes). “Reading is a part of the lab experiment in class, given as homework… [and]…students need to read, comprehend and analyze to pass this class” (#77, Biology). “We conduct debates to test out different claims in the reading” (#91, Speech Communication). “Students have to quote one main point and then write at least one paragraph in their own words on what they learned” (#121, Child Development).

Several content instructors reported that the readings are covered through lecture. Instructors also reported creating study guides for their students. “[Notes in the form of power point guide students to form questions] about the material before [they read] the text” (#80, Biology). “… Written study guides…indicate what questions students should be able to answer after doing the reading… [and] I have quizzes…” (#169, Anthropology). “I give some general questions that will direct the students [to consider]…key issues raised in [the] text…I ask that they come to [some conclusions before they begin reading]” (#191, English).

Instructors reported modeling critical thinking. “Often, I point out challenging thoughts or idioms and we clarify them together” (#56, English). “[Together] we analyze a wide variety of broadcast scripts, and discuss the genre and the format used” (#166, Broadcast Electronic Media Arts). “We do assessments by following rubrics for particular assignments and making sure descriptions are adequate and make sense in regards to the topics we have covered” (#14, Math).

Instructors also report providing resources. "Students take a VARK test [Visual – Aural – Read – Kinesthetic questionnaire that seeks to identify learning preferences] and a variety of resources are available to them on the course website with additional access to iTutors” (#81, Biological Sciences). “I don't have time to teach how to read the text, but I provide resources that students can choose to read if they need help” (#84, Psychology). “The reading material is linked and repeatedly reiterated in the tech-enhanced material… Sometimes, I refer BACK to a reading from a previous week…and ask that they reflect again with their new knowledge” (#92, Broadcast Electronic Media Arts).

A number of instructors motivate their students to complete readings in various ways. “I say, Read the required text this week…it may show up on a quiz” (#157, Environmental Horticulture and Floristry). “I explain the purpose of the reading and highlight what that reading is about to capture students' attention” (#161, Disabled Students Programs & Services). Some report giving highly personalized help. “[I] encourage students who are having [reading] difficulties…to come in during office hours… [and] show them how to break down each chapter to learn the main concepts” (#205, Fire Science Technology).

And one instructor came up with a creative solution when met with student resistance to reading. “I gave up getting students to read and created video tutorials to [mirror] all the assigned readings. If students only watch the videos, they can do fine. The better students do both: reading and watching video tutorials” (#140, Earth Sciences).

Depending on the course, instructors either check comprehension (sciences), or encourage students to develop critical reading skills. “I occasionally must interpret, but it's more important for me that students engage and possibly come up short than for me to digest text for them” (#191, English). “I sometimes interpret particularly difficult sections for students to help them relate them to page 24 of 75 the main ideas of the text, but primarily I encourage and challenge them to interpret the texts themselves, and I give time and space for them to practice this” (#181, English).

Although one instructor admitted that assignments did not require text responsibility, “Some manage to skate through this requirement by skimming, BS'ing, etc.” (#89, Business), all other responses showed that the reading and comprehending of assigned texts is essential to successful completion of the course. Rather than giving up on assigning readings, the Earth Sciences instructor added a non-text redundancy (video tutorials) to deliver the same content. Q11. What reading guidance do you offer outside of class? Check all that apply.

a. The students complete a questionnaire about their reading history/habits and I offer individualized feedback. (4%) b. I provide guiding questions to help them focus their reading. (56%) c. I provide the topic question for the paper they will write. (42%) d. If students are struggling with the readings, I suggest they read the chapter questions first in order to focus their reading. (22%) page 25 of 75 e. I require my students to annotate. (24%) f. I ask my students to turn in outlines for each reading assignment. (6%) g. I ask my students to turn in summaries for each reading assignments. (19%) h. Students fill out worksheets. (Please attach a sample worksheet if possible.) (19%) i. How a student approaches the texts is up to the individual student. (16%) To interpret the data for this question, it’s best to keep in mind that 40% of polled instructors are English or ESL instructors. The fourth choice, “If students are struggling with the readings, I suggest they read the chapter questions first in order to focus their reading,” is a typical strategy for approaching text chapters in the sciences.

One political science instructor found this question to be flawed (gave no explanation). Some answers show there was confusion about the meaning of my question.

From those who reported offering guidance outside the classroom, instructors describe using a wide variety of practices to support student reading. One instructor screens students. “Students complete a form at the beginning of the semester asking what level of English/ESL they have completed…If it’s ESL 150 or below, I ask students to meet with me and try to tell through these meetings, and also from talking to or calling on students in class, which students have difficulty comprehending either spoken or written English. Usually those with low reading levels lack sufficient basic vocabulary to do well in this class” (#156, Economics).

Instructors report giving individual feedback by reviewing annotation work (a number of instructors teach annotation explicitly, and in depth), journal assignments, and other writing tasks connected to reading assignments. “They write a weekly short paper on something from the reading that intrigues them, tying it back to a real-life example such as an ad they have seen that uses a principle from the text” (#89, Business). “I ask students to hand in annotated assigned readings the first 4 weeks of school. As the semester goes on, checking of annotations and summaries becomes random. [I post] "Credit or no credit" on Insight on the same day it is checked” (#115, Child Development).

Some instructors remarked that they only had time to offer selective feedback. “While I do teach outlining and require this of some texts, and the same of summaries, I do not do this for each text. I'd be overwhelmed” (#199, English). “I don't require outlines and summaries and worksheets for EACH assignment. I vary it a bit and, as the semester progresses, I move towards less structured guidance” (#180, English).

Instructors report using a variety of modes to give students reading support outside the classroom, including that offering guiding questions, asking students to participate in on-line forums, offering post-reading activities/assignments, requiring students to use Reading Plus, an on-line reading program for English students, and discussing the nature of reading. “We do talk about reading habits: where they read, how long at a time they read, what sorts of things throw them off the track—I ask that they make note of when they give up or drift away and become conscious of that moment of disengagement—or, conversely, what sorts of readings don't throw them off. It is not that we should expect constant interest but that we must recognize when we are thrown off and devise a strategy for reintegration with the work” (#191, English). page 26 of 75

Instructors also encourage students to use college resources (e.g., tutoring services). “We have virtual tutors and the students have an opportunity to submit their FIRST assignment for comments with the option to re-submit revisions” (#81, Biology).

Two content instructors reported teaching students to outline during office hours (Psychology; Fire Sciences). Although no other instructors explicitly stated that they work with students during office hours, providing office help was mentioned often for Q16 (see below).

Q12. How often do you assess whether students understand the texts you’ve assigned?

Instructors report using on-going informal (class discussions; oral quizzes) and a variety of formal assessments, including written quizzes, tests, mid-terms, finals, and written assignments. “I also assess their understanding in weekly writing assignments…where they apply concepts learned in class… [and] from the textbook” (#122, Biological Sciences).

ESL instructors report assessing daily and English instructors report assessing for each text. “Most of the semester is spent in me assessing how well the students are completing and understanding the readings I assign” (#181, English).

Content instructors more commonly reported using a set number of quizzes (typically 4-5 throughout the semester), the midterm, and the final to assess. Several instructors are using technology (i.e., iclickers; on-line forum discussions). Several content instructors report assessing specific outcomes through direct observation. “[Students show they understand readings by] demonstrating correct hands-on assessments of the medical condition presented” page 27 of 75

(#205, Fire Science Technology). “Assessment is done through application of the content (designing the study guide layout), rather than written tests” (#220, Visual Media Design). “Students are assigned…to lead discussions on popular science articles” (#75, Biology).

Other instructors report relying on subjective measures. “We talk about the reading in class and I am in a good position to judge who gets it or not” (#174, Library Information Technology). “… Through discussion and hands-on work in class. I don't formally assess, but if they student is lost it becomes clear and they work to get caught up” (#89, Business). “From the main points or questions students answer each week, I can see if they understand some of the concepts. Some are still having challenges writing—using their own words. This is just after the midterm” (#121, Child Development).

Some instructors identified problems with assessment. “I assess the class "as a whole" probably weekly, but of course quieter or weaker students may get overlooked” (#48, ESL). “Not enough.... I need more tools for assessing basic comprehension…When I conference with them, I ask students to show me examples of how they are marking the text and use that as a springboard to talk about the reading and informally assess their comprehension. Also, their use of textual evidence to support their essay argument provides another window into their comprehension of the issues” (#68, English). “Students do online homework problems and exam problems that test their understanding of the techniques and formulas in the book and lecture. This may or not correlate to their understanding of the text” (#124, Physics). “I do not exactly understand this question. I check in every class whether students understand the concepts and terminology under discussion. But often they don't do the reading until after I present the material—except last year, when I used specific assignments on the reading before class discussion—” (#156, Economics).

Q13. How do you use the assessment you do of your students’ reading comprehension?

Assessments on reading comprehension are part of a student’s grade. 64 (42%) I use reading assessments to monitor my students’ reading comprehension and offer additional instruction as necessary. 86 (56%) Sixty four instructors (42%) count assessments of reading (quizzes, mid-terms, finals) as part of a student’s grade, but most reported that quiz, test, and course grades only indirectly reflected page 28 of 75 reading comprehension. Those that graded reading comprehension commented that the weight was low. “Not a large part of the grade” (#75, Biological Sciences). “If done at all, 10% of the course grade” (#80, Biology). “There are no grades, but I do use this information in determining whether or not a student has met the course’s Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs)” (#39, ESL).

Similar to comments instructors made about direct reading instruction, instructors again revealed that while reading is not being assessed directly, reading comprehension is strongly linked to both assignment and course success. “I assess student projects to ascertain how much of the reading material they were able to use in their work” (#163 Broadcast Electronic Media Arts). “Tests are based on the reading, so how well they comprehended the reading will be reflected in the test scores” (#209 Health Care Technology). “Study Guide layouts are a part of the grade” (#220 Visual Media Design). “[I use assessment] to see how well they are able to incorporate what they learn via class/textbook and [how well they can] critically evaluate research and proposed solutions to environmental problems” (#122 Biological Sciences).

Eighty six instructors (56%) reported using reading assessment to monitor student comprehension and offer additional instruction. “Sometimes I must repeat everything or go over certain subjects several times” (#7, Culinary Arts/ Hospitality Management). “I go back over things, often” (#102, ESL). Many used reading assessments to adjust teaching. “I use them primarily to inform my own teaching and evaluation of the students' writing” (#133, ESL). “Assessment of reading also informs the type of essay assignments I create” (#59, English). “I use evidence of struggle to refine how I teach the readings in the future” (#185, English). And many use the assessments to encourage individual students. “I use them mainly to inform the students of their challenges to encourage them to spend time on task. Many students severely underestimate the value of this” (#53, English). “I speak individually to those falling through cracks” (#62, English). “My [students] vary in demographics and previous educational experiences. I must assess each student independently, spending most of my time with the remedial students, who are taking their first course, with technical and multiple reading assignments each week. It is a subject matter that they are drawn to and gives them the impetus to take more courses in math and electronics to understand the world of audio engineering” (#92 Broadcast Electronic Media Arts). “Students who appear to be struggling, I meet with and discuss course requirements and assignments and try to determine issues affecting student performance” (#210 Fire Science Technology). “[The] class is designed for students who have serious intellectual disabilities, to help them find work. Reading and writing levels are very important for what sort of jobs they can reasonably manage. I assess literacy levels to help them apply for the appropriate jobs and find the assistance and services they need” (#214, Disabled Students Programs and Services). “I comment on their forum posts. If I feel they misunderstood the article, I will discuss it with them” (#134, Broadcast Electronic Media Arts).

One instructor states that assessments are guides for students. “Formative and Summative assessment. Students use results as indicators of their own understanding” (#140, Earth Sciences).