Declining US Marriage Rates

I. Some Background Information

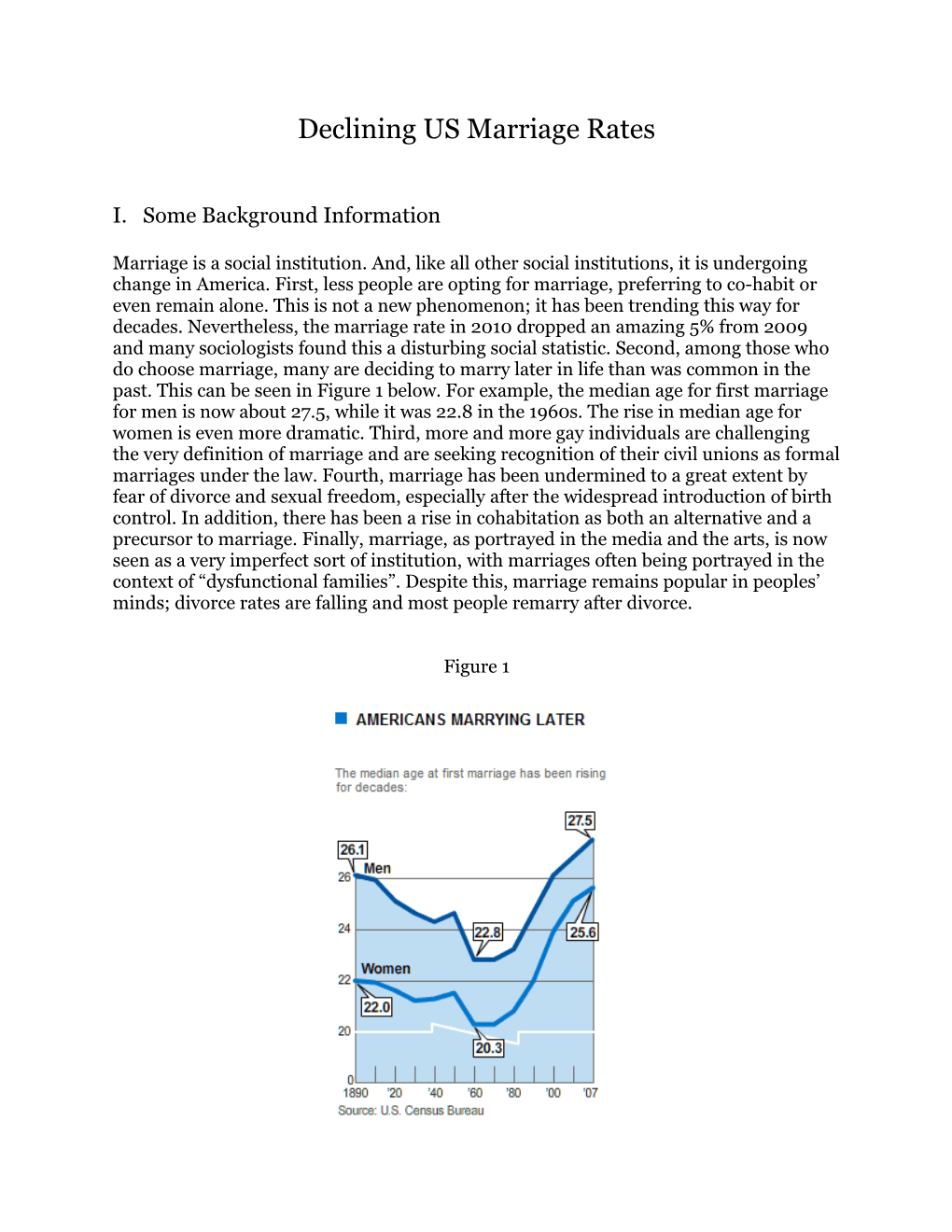

Marriage is a social institution. And, like all other social institutions, it is undergoing change in America. First, less people are opting for marriage, preferring to co-habit or even remain alone. This is not a new phenomenon; it has been trending this way for decades. Nevertheless, the marriage rate in 2010 dropped an amazing 5% from 2009 and many sociologists found this a disturbing social statistic. Second, among those who do choose marriage, many are deciding to marry later in life than was common in the past. This can be seen in Figure 1 below. For example, the median age for first marriage for men is now about 27.5, while it was 22.8 in the 1960s. The rise in median age for women is even more dramatic. Third, more and more gay individuals are challenging the very definition of marriage and are seeking recognition of their civil unions as formal marriages under the law. Fourth, marriage has been undermined to a great extent by fear of divorce and sexual freedom, especially after the widespread introduction of birth control. In addition, there has been a rise in cohabitation as both an alternative and a precursor to marriage. Finally, marriage, as portrayed in the media and the arts, is now seen as a very imperfect sort of institution, with marriages often being portrayed in the context of “dysfunctional families”. Despite this, marriage remains popular in peoples’ minds; divorce rates are falling and most people remarry after divorce.

Figure 1 Since the beginnings of the 1970s the US has experienced a secular decline in marriage rates. The marriage rate for people 25-34 years of age, having high school education or less, has been continuously falling at slightly less than 1.5% per year. In 1970 the marriage rate for this cohort was about 80%. It now stands at about 45%. For people having a bachelor’s degree or higher the rate also fell from 1970 to 1990 and then stabilized more or less. In 1972 the rate for this particular cohort was about 72%, but by 1990 it had fallen to around 58%. The rate currently stands at slightly above 50%.

Figure 2

Stevenson and Wolfers (2007) of the NBER consider some salient trends in US marriage over the past 150 years. They state in their abstract1

While divorce rates have risen over the past 150 years, they have been falling for the past quarter century. Marriage rates have also been falling, but more strikingly, the importance of marriage at different points in the life cycle has changed, reflecting rising age at first marriage, rising divorce followed by high remarriage rates, and a combination of increased longevity with a declining age gap between husbands and wives. Cohabitation has also become increasingly important, merging as a widely used step on the path to marriage. Out-of-

1 See Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, Marriage and Divorce: Changes and their Driving Forces, NBER Working Paper No. 12944, March 2007. wedlock fertility has also risen, consistent with declining "shotgun marriages". Compared with other countries, marriage maintains a central role in American life. We present evidence on some of the driving forces causing these changes in the marriage market: the rise of the birth control pill and women's control over their own fertility; sharp changes in wage structure, including a rise in inequality and partial closing of the gender wage gap; dramatic changes in home production technologies; and the emergence of the internet as a new matching technology. We note that recent changes in family forms demand a reassessment of theories of the family and argue that consumption complementarities may be an increasingly important component of marriage.

Having verified that there is indeed a declining marriage rate in the US, can we say that this is an undesirable social phenomenon? Why should there be marriage at all? What is the social value of marriage?

To begin with, it must be acknowledged that society in the past saw an intrinsic value to the institution of marriage – that is why it arose in the first place. Throughout US history, marriage was widespread and relatively stable. If marriage is no longer being sought by Americans, it is because US society today is vastly different than it was in the past. However, even today, most individuals eventually get married and most claim that marriage is a good thing.

Generally speaking social science studies of the benefits of marriage have been concentrated in looking at the effect marriage has on (1) child well-being, (2) adult earnings, and (3) adult physical health and mortality. These studies tend to show a high and positive correlation or linear association between the three indicators and marriage. Marriage appears to be good for people. As Ribar more objectively puts it 2

While the associations between marriage and various measures of well-being have been convincingly established, the associations do not, by themselves, make a compelling case that marriage has beneficial effects. As with many other types of social science data, the empirical relationships are likely to be confounded by problems of reverse causality and spurious correlation from omitted variables.

A report, specifically aimed at looking at the benefits of marriage, was developed by the Institute for American Values, which commissioned sixteen distinguished scholars from numerous respected universities. The results were a collection of 26 different beneficial effects from marriage. With respect to economics the panel found3

2 David C. Ribar, What Do Social Scientists Know About the Benefits of Marriage: A Review of Quantitative Methodologies, IZA DP No. 998, Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor, January, 2004 (p.1). 3 W. Bradford Wilcox, William Doherty, Norval Glenn, Linda Waite, et al., Why Marriage Matters: Twenty-Six Conclusions from the Social Sciences, 2nd Edition, Institute for American Values, 2005. Economics

1. Divorce and unmarried childbearing increase poverty for both children and mothers. 2. Married couples seem to build more wealth on average than singles or cohabiting couples. 3. Marriage reduces poverty and material hardship for disadvantaged women and their children. 4. Minorities benefit economically from marriage. 5. Married men earn more money than do single men with similar education and job histories. 6. Parental divorce (or failure to marry) appears to increase children’s risk of school failure. 7. Parental divorce reduces the likelihood that children will graduate from college and achieve high-status jobs.

Health and Longevity

1. Children who live with their own two married parents enjoy better physical health, on average, than do children in other family forms. 2. Parental marriage is associated with a sharply lower risk of infant mortality. 3. Marriage is associated with reduced rates of alcohol and substance abuse for both adults and teens. 4. Married people, especially married men, have longer life expectancies than do otherwise similar singles. 5. Marriage is associated with better health and lower rates of injury, illness, and disability for both men and women. 6. Marriage seems to be associated with better health among minorities and the poor.

The above represents only half of the conclusions reached by the scholars. It would be difficult to argue against the totality of these results even if there were some so-called selectivity problems associated with parts of the research.

What has the US government done to promote marriage in America? There have been numerous programs set up under different administrations. The usefulness of these programs in keeping children in stable and functional families (as opposed to handing children over to foster homes) is quite limited. As one report states4

Although there is debate among practitioners, research suggests that family preservation programs have very modest effects on family and child functioning. Researchers have found few significant differences between program and comparison groups in levels of child and families functioning after services have been provided.

4 See NRCFCPP Information Packet: Promoting Safe & Stable Families, 2002 (p.6) http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/socwork/nrcfcpp/downloads/information_packets/safe_and_stable_families-pkt.pdf As with most social programs, policies designed to enhance marriage and child-caring require effort on both sides, not just the government. A discussion of federal programs to 2002 is available at the government website http://www.childwelfare.gov/supporting/support_services/programs.cfm

II. A Simple Model of Marriage and Potential Job Changes

Suppose that person 1 has a utility function, U1, that depends on his own consumption, 2 c1, and the utility of person 2, U . We will assume that these two individuals are identical in preferences. This means that U2 must depend on both c2 and U1. The utility of person 1 can be written in implicit form as

1 1 2 1 U= U[ c1 , U ( c 2 , U )]

Under conditions given by the implicit function theorem, U1 can be solved explicitly as

U1 = ( c , c ) f 1 2 (1)

Now suppose that person 1 and person 2 decide to marry and their separate incomes (or endowments) are given by y1 and y2. Marriage yields a combined income ym such that

y= y + y = c + c m 1 2 1 2 (2)

if there is no scale economies in production or consumption due to marriage. The household maximizes (1) subject to (2). This yields the indirect function

U1 ( y )= ( y ) ** mf m . Now suppose that person 1 has the choice of continuing to look for employment at a location that makes marriage inconvenient, at the very least. We can assume that there are two employment states for the single person 1 – one which has income ym + h with probability p and another which has income ym – h with probability (1-p) . Person 1 must make a decision about whether it is better to remain in place and marry or pursue a career elsewhere with income risk. Clearly many married couples face this possibility with both individuals working and both subject to job displacement for one reason or another. Knowledge of this beforehand must undoubtedly make the marriage decision complicated, especially if there are considerable impediments to moving after marriage takes place. Not only does marriage (and children and other commitments) limit one in terms of which jobs can be taken in a locality, it cannot guarantee one’s current job will be stable. Thus, marriage becomes as permanent as one’s employment in a single location. In a world of globalization and creative destruction, the institution of marriage must also be subject to globalization and creative destruction. Those marriages that survive are those that are based on a set of employment opportunities that are relative safe from the forces of competition. It must be such that both individuals do not expect pressure to leave due to unemployment or advancement. In short, it simply may not be possible in today’s world to find a stable job on which a stable marriage can be predicated. Recognizing this, individuals will opt for an uncertain single life that nevertheless provides for freedom of choice, advancement, and movement, until such time as the probability of finding a better job is sufficiently reduced, the joint income from marriage is sufficiently high, the potential improvement that can be obtained from moving as a single person falls, or the care one has for another person rises sufficiently high. Each of these is likely to occur at an older age rather than at a younger age.

Given the two possible outcomes of remaining single and pursuing a better job elsewhere, person 1 can expect to have utility equal to5

2 U** = pU( ym (1 + h )) + (1 - p ) U ( y m / (1 + h )) = y ( y m , p , h )

where U( c1 ) is the utility function of person 1 while single. And where p > ½.

It follows that person 1 will want to marry if

5 We have assumed symmetric outcomes (one multiplied by (1=h) the other divided by (1+h)) for purposes of simplification. There is no need for this and introducing asymmetric outcomes would not affect the results. f(ym )> y ( y m , p , h ) .

and will wish to remain single otherwise.

Example: Let the utility of person 1 be written as

1 2 U=alog( c1 ) + h U 1 =alog(c1 ) + h [ a log( c 2 ) + h U ]

This can be solve explicitly for U1 as

1 1 U=2 [a log( c1 ) + ah log( c 2 )] (1- h )

a We can, of course, ignore the proportionality factor 2 and write this as a log linear (1- h ) function in the following manner

U1 =[log( c ) + log( c )] 1h 2 (3)

Note how that the utility function now depends only on the interlocking parameter, η. That is, person 1’s utility is crucially dependent on the strength of the feeling he had towards person 2. The parameter η transforms 2’s utility into 1’s utility.

Maximization of (3) subject to (2) yields the following indirect utility function 1+h h 1 ym h U* =f( ym , h ) = log[1+ ] (1+h ) h

while the expected utility from pursuing potential employment as a single individual can be written

1 2p- 1 U** =y ( ym , p , h ) = log[ y m (1 + h ) ]

and thus the difference between (married) indirect utility and (single) expected utility is equal to

h h 1 1 ymh D �U** = U * log{1+ 2p - 1 } (1+h )h (1 + h )

note that a rise in marriage income ym increases Δ and thus increases the likelihood that person 1 will marry. In addition, it is not hard to show, using the envelope theorem, that a rise in hwill increase Δ. By contrast, a rise in h or in p will tend to reduce Δ and thus reduce the chances of marriage.

III. Some Alternative Reasons for the Decline in Marriage

The model we have presented shows abstractly how that the marriage rate might fall over time due to globalization and creative destruction. Are there other reasons for the fall in marriage rates? Of course, here are a few considerations

(1) increased cohabitation substituting for formal marriages

(2) bad economy with marriages on average costing upwards of $30,000 USD for the weddings only.

(3) experience in the past with high divorce rates coupled with high divorce costs making marriage a risky business (4) the increasing need to first accumulate sufficient wealth is raising the marrying age

(5) difficulty in finding men who have salaries at or above women (especially a problem in minority cases) – a general dearth of acceptable men

(6) particular social changes (e.g. less complementary consumption, proliferation of rentals, etc.) that have accommodated single life

(7) the substitution of pets and the internet as substitutes for marital companionship

(8) increased use of birth control making marriage unnecessary in some cases

Discussion Questions:

#1. What evidence is there that the marriage rate in the US is falling? When did it begin?

#2. In what ways is it rational to co-habit instead of marry?

#3. Is the rising trend in unmarried births a good thing? Does it matter?

#4. What factor does our mathematical model show is at play in declining marriage rates? Explain how globalization and creative destruction is making marriage unstable.

#5. Why is it so difficult to use public policy to stabilize families?

#6. Why are people getting married for the first time at an older age?

#7. What benefits does marriage bring to society?

#8. Will marriage still be part of US society in the 22nd century? Why or why not?