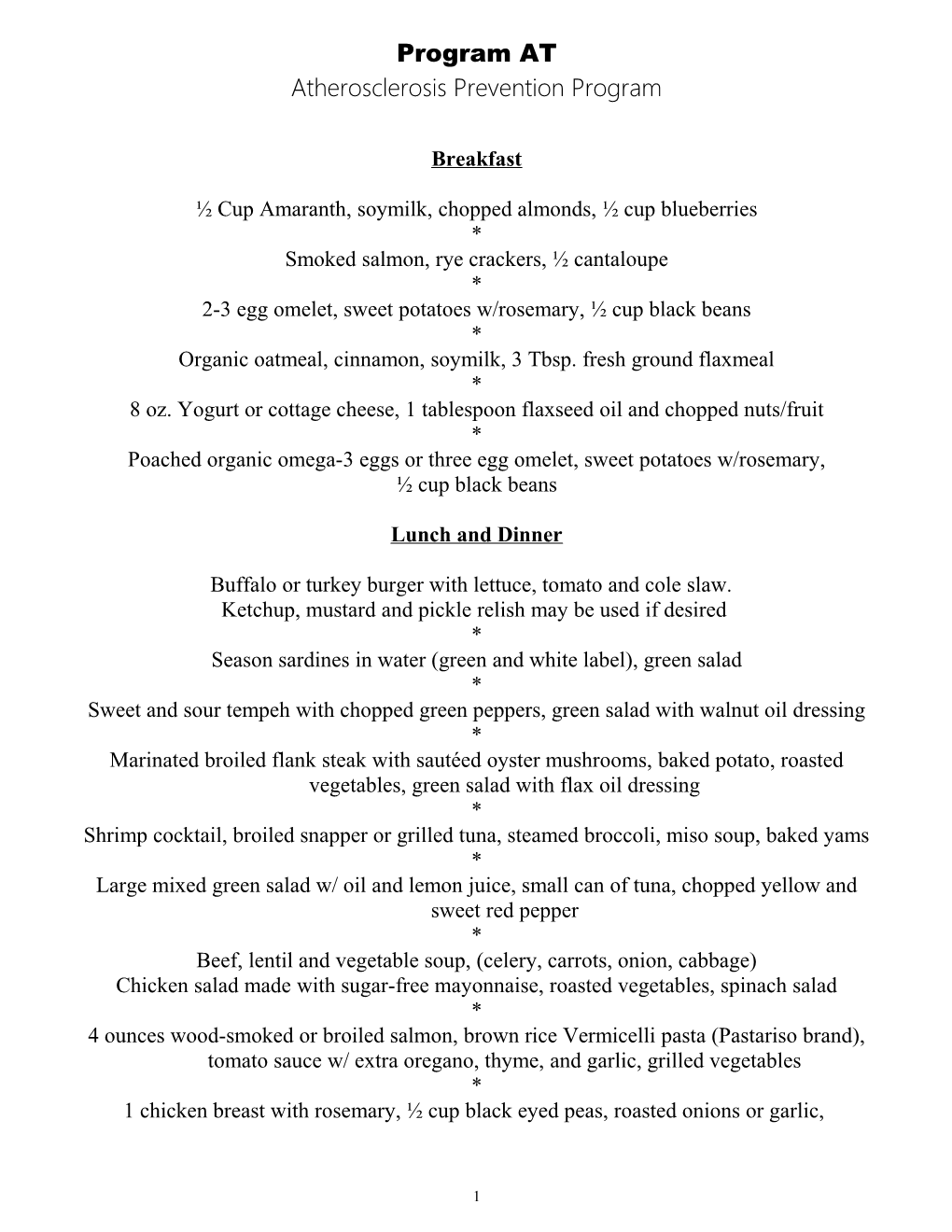

Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program

Breakfast

½ Cup Amaranth, soymilk, chopped almonds, ½ cup blueberries * Smoked salmon, rye crackers, ½ cantaloupe * 2-3 egg omelet, sweet potatoes w/rosemary, ½ cup black beans * Organic oatmeal, cinnamon, soymilk, 3 Tbsp. fresh ground flaxmeal * 8 oz. Yogurt or cottage cheese, 1 tablespoon flaxseed oil and chopped nuts/fruit * Poached organic omega-3 eggs or three egg omelet, sweet potatoes w/rosemary, ½ cup black beans

Lunch and Dinner

Buffalo or turkey burger with lettuce, tomato and cole slaw. Ketchup, mustard and pickle relish may be used if desired * Season sardines in water (green and white label), green salad * Sweet and sour tempeh with chopped green peppers, green salad with walnut oil dressing * Marinated broiled flank steak with sautéed oyster mushrooms, baked potato, roasted vegetables, green salad with flax oil dressing * Shrimp cocktail, broiled snapper or grilled tuna, steamed broccoli, miso soup, baked yams * Large mixed green salad w/ oil and lemon juice, small can of tuna, chopped yellow and sweet red pepper * Beef, lentil and vegetable soup, (celery, carrots, onion, cabbage) Chicken salad made with sugar-free mayonnaise, roasted vegetables, spinach salad * 4 ounces wood-smoked or broiled salmon, brown rice Vermicelli pasta (Pastariso brand), tomato sauce w/ extra oregano, thyme, and garlic, grilled vegetables * 1 chicken breast with rosemary, ½ cup black eyed peas, roasted onions or garlic,

1 Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program

spinach salad with goat cheese, walnuts and balsamic vinegar/walnut oil dressing * Salmon burger patties made with 6 oz. chopped salmon, onions, dill, an egg, and ¼ cup ground sesame seeds, and sautéed in skillet with 1 Tbsp. butter

Snacks Roasted garlic or almond butter on rice cake or celery, protein shakes with freshly ground flaxseeds added, handful of raw almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts, brazil nuts, or sesame seeds, an organic apple, pear, or grapes, sugar-free yogurt, rice cakes with nut butter, 2 oz. cheese, lean hormone free meat with mustard, hard boiled egg

Beverages 8 oz. fresh mixed vegetable juice 1-2x per day Green drinks: Green Magma, Kyogreen, or Green Kamut: 1 tsp. 1-3x day in water Herbal Teas: Licorice, Chamomile, Ginger, Green Tea

Avoid Smoking, cholesterol lowering medications, caffeine, sugar, hydrogenated oils, safflower, sunflower, corn oils, soft drinks, processed meats, refined or processed foods

Supplements Niacin/Inositol Hexanicotinate 300-600 mg Chromium 400 mcg Carnitine 1-3 grams (½ to 1 hour before breakfast and lunch) Vitamin C 1-3 grams Vitamin E 400-800 IUs B complex 50 mg Folic Acid 500 mcg B12 500 mcg Gamma and Delta tocotrienols 100-300 mg CoQ10 60 mg (especially for those on statin drugs) Copper Sebacate 2 mg Taurine 1-2 grams Phosphatidyl Choline 420 mg GLA 480 mg of GLA (Two capsule of GLA 240 mg) Fiber 1-3 Tbsp. of fiber (Ground Flaxmeal best)

2 Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program

Research Review

Higher Cholesterol and Higher Weight Helps Adults Over 65 Live Longer… A total of 5201 and 685 men and women aged 65 years or older in the original and African American cohorts, respectively, were studied. Neither high-density lipoprotein cholesterol nor low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was associated with mortality. Those with higher cholesterol levels and higher weight lived longer.1

In 724 participants (median age 89 years), total cholesterol concentrations were measured and mortality risks calculated over 10 years of follow-up. In people older than 85 years, high total cholesterol concentrations are associated with longevity owing to lower mortality from cancer and infection. The effects of cholesterol-lowering therapy have yet to be assessed.2

…but Lowering Cholesterol Still Benefits Younger Age Groups. We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE from 1966 through October 1996 for randomized, controlled trials of any cholesterol-lowering interventions reporting mortality data. We included 59 trials involving 85 431 participants in the intervention and 87 729 participants in the control groups. We pooled these trials into 7 pharmacological categories of cholesterol- lowering interventions: statins (13 trials), fibrates (12 trials), resins (8 trials), hormones (8 trials), niacin acid (2 trials), n-3 fatty acids (3 trials), and dietary interventions (16 trials). Of the cholesterol-lowering interventions, only statins showed a large and statistically significant reduction in mortality from coronary heart disease (risk ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54 to 0. 79) and from all causes (risk ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.86). Meta- regression analysis demonstrated that variability in results across trials could be largely explained on the basis of differences in the magnitude of cholesterol reduction.3

This overview of all published randomized trials of statin drugs demonstrates large reductions in cholesterol and clear evidence of benefit on stroke and total mortality. There was, as expected, a large and significant decrease in CVD mortality, but there was no significant evidence for any increases in either non-CVD deaths or cancer incidence.4

Mediterranean Diet This study showed that isoenergetic substitution of MUFAs for SFAs reduces plasma cholesterol and reduces the degree of postprandial factor VII activation. This study presents new insights into the biochemical basis of the beneficial effects associated with long-term dietary MUFA consumption, which may explain the lower rates of coronary mortality in Mediterranean regions.5

Fish Consumption A total of 20 551 US male physicians 40 to 84 years of age and free of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, and cancer at baseline who completed an abbreviated, semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire on fish consumption and were then followed up to 11 years. After controlling for age, randomized aspirin and beta carotene assignment, and coronary risk factors, dietary fish intake was

3 Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program associated with a reduced risk of sudden death, with an apparent threshold effect at a consumption level of 1 fish meal per week (P for trend=.03). These prospective data suggest that consumption of fish at least once per week may reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death in men.6

Trans Fats Our results show that the trans fatty acids decrease high density lipoprotein through their inhibition of lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) activity, and also alter LCAT's positional specificity, inducing the formation of more saturated cholesteryl esters, which are more atherogenic.7 Meal Frequency OBJECTIVES: To evaluate the effect of a single evening meal (gorging) on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in normal individuals observing the Ramadan Fast. Twenty-two healthy subjects who fasted during Ramadan and 16 non-fasting laboratory workers, were studied before Ramadan, at week 1, 2 and 4 of the Ramadan month, and again four weeks after the end of Ramadan. Plasma HDL increased by 23% after four weeks of gorging. The dietary change did not affect the composition of other lipoproteins, such as LDL, VLDL or Lp(a), other plasma biochemical parameters, or BMI. Prolonged gorging, well tolerated by all individuals, is a very effective non-pharmacological method to increase plasma HDL-cholesterol.8 Soy Foods The relationship between soy product intake and serum total cholesterol concentration was examined in 1242 men and 3596 women who participated in an annual health check-up program in Takayama City, Japan, provided by the municipality in 1992. A significant trend (P for trend = 0. 0001) was observed for decreasing total cholesterol concentration with an increasing intake of soy products in men after controlling for age, smoking status and intake of total energy, total protein and total fat. This negative trend (P for trend = 0.0001) was also noted in women after controlling for age, menopausal status, body mass index and intake of total energy and vitamin C. These data suggest a role for soy products in human cholesterol homeostasis.9 Soy Protein Regardless of plasma lipid status, the soy-protein diet was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the plasma concentrations of LDL cholesterol (P = 0.029) as well as the in the ratio of plasma LDL cholesterol to HDL cholesterol (P = 0.005).10 Textured Vegetable Soy Protein This study shows that TVP decreases serum LDL cholesterol (an effect of borderline significance in this study), an effect that occurs via a reduction in the absorption of cholesterol and perhaps bile acid. However, the potential benefit of decreasing LDL cholesterol in this way seems to be at least partially offset by a concomitant reduction in HDL cholesterol and an increase in serum triglycerides.11 Homocysteine, Vitamins B6, B12 and Folate

4 Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program

An elevated plasma homocysteine level is an established risk factor for atherosclerotic coronary heart disease (CHD), cerebrovascular disease (CVD), and lower extremity occlusive disease (LED). An elevated plasma homocysteine level can be reduced by therapy with folate and vitamins B6 and B12.12

Vitamin E

In this double-blind, placebo-controlled study with stratified randomization, 2002 patients with angiographically proven coronary atherosclerosis were enrolled and followed up for a median of 510 days (range 3-981). 1035 patients were assigned alpha-tocopherol (capsules containing 800 IU daily for first 546 patients; 400 IU daily for remainder); 967 received identical placebo capsules. Alpha-tocopherol treatment significantly reduced the risk of the primary trial endpoint of cardiovascular death and non-fatal MI (41 vs 64 events; relative risk 0.53 [95% Cl 0.34- 0.83; p=0.005). The beneficial effects on this composite endpoint were due to a significant reduction in the risk of non-fatal MI (14 vs 41; 0.23 [0.11- 0.47]; p=0.005). We conclude that in patients with angiographically proven symptomatic coronary atherosclerosis, alpha-tocopherol treatment substantially reduces the rate of non-fatal MI, with beneficial effects apparent after 1 year of treatment. 13

Tocotrienols

Tocotrienols are natural products that exhibit hypocholesterolemic activity in vitro and in vivo. The synthetic (racemic) and natural (chiral) tocotrienols exhibit nearly identical cholesterol biosynthesis inhibition and HMG-CoA reductase suppression properties as demonstrated in vitro and in vivo.14

Magnesium

We examined the relation of serum and dietary magnesium with CHD incidence in a sample of middle- aged adults (n=13,922 free of baseline CHD) from 4 US communities. Over 4 to 7 years of follow-up, 223 men and 96 women had CHD develop. These findings suggest that low magnesium concentration may contribute to the pathogenesis of coronary atherosclerosis or acute thrombosis.15

Copper

Bone disease and cardiovascular disease from diets-low in copper have been studied in animals for decades. Men and women fed diets close to 1 mg of copper per day, amounts quite frequent in the US, responded similarly to deficient animals with reversible, potentially harmful changes in blood pressure control, cholesterol and glucose metabolism, and electrocardiograms. Ischemic heart disease and osteoporosis are likely consequences of diets low in copper.16 The present study examined the effects of copper supplementation (2 mg/d for 4 weeks in a copper/placebo crossover design) in 20 adult men with moderately high plasma cholesterol. Although copper had no significant effects on any parameter for the entire study group, it did significantly increase

5 Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program two enzyme activities (SOD and DAO), as well as lipoprotein oxidation lag times, in 10 subjects in the lower half of a median split for precopper values.17

Excess Iron Promotes Atherosclerosis in an Animal Model Iron deposition is evident in human atherosclerotic lesions, suggesting that iron may play a role in the development of atherosclerosis. Our results clearly demonstrated that iron deposits are present in atherosclerotic lesions and tissue sections of heart and liver in an age-dependent manner. When the young mice received a low- iron diet for 3 months, the hematocrit, serum iron, hemoglobin, and cholesterol concentrations were not significantly altered compared with those of littermates placed on a chow diet. However, the serum ferritin level of animals in the iron-restricted group was 27% to 30% lower than that of the control group in either sex. Furthermore, the lipoproteins isolated from the iron-restricted group exhibited greater resistance to copper-induced oxidation. Histological examination revealed that atherosclerotic lesions developed in mice fed a low-iron diet were significantly smaller than those found in control littermates. Likewise, the iron deposition as well as tissue iron content was much less in aortic tissues of the iron-restricted animals. Circulating autoantibodies to oxidized LDL and immunostains for epitopes of malondialdehyde-modified LDL detected on lesions were also significantly lower in mice fed a low-iron diet. These results suggest that the beneficial effect of a low-iron diet may be mediated, at least in part, by the reduction of iron deposition as well as LDL oxidation in vascular lesions.18

Carnitine The effect of L-C on plasma lipoprotein fatty acids pattern was investigated in 24 male and female hyperlipoproteinemic patients, aged 51.3 +/- 7.8 years (lipoprotein phenotypes: IIb and IV, WHO, 1970). After hypolipidemic diet (P, 22%; C, 48%; L, 30%; S, 10%; M, 10%; PV, 10%, cholesterol 300 mg/d) lasting 30 days, L-C was given at a daily dosage of 1 g t.i.d. for 90 days. Plasma levels of total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol were reduced after one month. A less atherogenic plasma lipoprotein fatty acids profile was observed after 120 days of combined treatment with diet and L-Carnitine.19

These results indicate that L-carnitine affects the cholesterol metabolism through an inhibition of HMG- CoA reductase activity that could be responsible for the increased [125I]LDL binding in rat hepatocytes.20

CoQ10

Forty-five hypercholesterolemic patients were randomized in a double-blind trial in order to be treated with increasing dosages of either lovastatin (20-80 mg/day) or pravastatin (10-40 mg/day) over a period of 18 weeks. Serum levels of coenzyme Q10 were measured parallel to the levels of cholesterol at baseline on placebo and diet and during active treatment. A dose-related significant decline of the total serum level of coenzyme Q10 was found in the pravastatin group from 1.27 +/- 0.34 at baseline to 1.02 +/- 0.31 mmol/l at the end of the study period (mean +/- S.D.), P 0.01. After lovastatin therapy the decrease was significant as well and more pronounced, from 1.18 +/- 0.36 to 0.84 +/- 0.17 mmol/l, P 0.001. Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors are safe and effective within a limited time horizon, continued vigilance of a possible adverse consequence from coenzyme Q10 lowering seems important during long-term therapy.21

6 Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program

Taurine Lowers Lipids in Animal Study

Taurine lowers cholesterol and triglycerides in rats whose cholesterol is high or normal.22

GLA

Nineteen hypercholesterolemic patients (10 without and 9 with hypertriglyceridemia) were given evening primrose oil rich in gammalinolenic acid (GLA, 18: 3n - 6), in a placebo controlled cross- over design, over 16 weeks (8 + 8 weeks), with safflower oil as the placebo. Our results confirmed that evening primrose oil is effective in lowering low density lipoprotein in hypercholesterolemic patients.23

Aging is characterized by a wide variety of defects, particularly in the cardiovascular and immune systems. Cyclic AMP levels fall, especially in lymphocytes. Delta-6-desaturase (D6D) levels have been found to fall rapidly in the testes and more slowly in the liver in aging rats. D6D is an enzyme which converts cis-linoleic acid to gamma- linolenic acid (GLA). Other factors which inhibit D6D activity are diabetes, alcohol and radiation, all of which may be associated with accelerated aging. In meat eaters or omnivores which can acquire arachidonic acid from food, the main consequences of D6D loss will be deficiencies of GLA, dihomogamma-linolenic acid (DGLA) and prostaglandin (PG) E1. PGE1 activates T lymphocytes, inhibits smooth muscle proliferation and thrombosis, is important in gonadal function and raises cyclic AMP levels in many tissues. It is a good candidate for a key factor lost in aging. Moderate food restriction, the only maneuver which consistently slows aging in homoiotherms, raises D6D activity by 300%. Other factors important in regulating D6D and the conversion of GLA to PGE1 are zinc, pyridoxine, ascorbic acid, the pineal hormone, melatonin, and possibly vitamin B3. GLA administration to humans has been found to lower blood pressure and cholesterol, and to cause clinical improvement in patients with Sjogren's syndrome, scleroderma and alcoholism. The proposition that D6D loss is not only a marker of aging but a cause of some of its major manifestations is amenable to experimental test even in humans. The blocked enzyme can be by-passed by giving GLA directly.24

CLA

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) consists of a series of positional and geometric dienoic isomers of linoleic acid that occur naturally in foods. CLA exhibits antioxidant activity in vitro and in vivo. To assess the effect of CLA on atherosclerosis, 12 rabbits were fed a semi- synthetic diet containing 14% fat and 0.1% cholesterol for 22 weeks. For 6 of these rabbits, the diet was augmented with CLA (0.5 g CLA/rabbit per day). Blood samples were taken monthly for lipid analysis. By 12 weeks total and LDL cholesterol and triglycerides were markedly lower in the CLA-fed group. Interestingly, the LDL cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio and total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio were significantly reduced in CLA-fed rabbits. Examination of the aortas of CLA-fed rabbits showed less atherosclerosis.25

In both the aggregation and arachidonic acid metabolism experiments, the inhibitory effects of CLA on platelets were reversible and dependent on the time of addition of either the aggregating agent or the [14C]arachidonic acid substrate. These studies suggest that CLA isomers may also possess antithrombotic properties.26

7 Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program

Guggulipid

The effects of the administration of 50 mg of guggulipid or placebo capsules twice daily for 24 weeks were compared as adjuncts to a fruit- and vegetable-enriched prudent diet in the management of 61 patients with hypercholesterolemia (31 in the guggulipid group and 30 in the placebo group) in a randomized, double-blind fashion. Guggulipid decreased the total cholesterol level by 11.7%, the low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) by 12.5%, triglycerides by 12.0%, and the total cholesterol/high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio by 11.1% from the postdiet levels, whereas the levels were unchanged in the placebo group. The HDL cholesterol level showed no changes in the two groups. The lipid peroxides, indicating oxidative stress, declined 33.3% in the guggulipid group without any decrease in the placebo group. The compliance of patients was greater than 96%. The combined effect of diet and guggulipid at 36 weeks was as great as the reported lipid-lowering effect of modern drugs.27

Two hundred and five patients completed 12 week open trial with gugulipid in a dose of 500 mg tds after 8 week diet and placebo therapy. A significant lowering of serum cholesterol (av. 23.6%) and serum triglycerides (av. 22.6%) was observed in 70-80% patients. HDL-cholesterol was increased in 60% cases who responded to gugulipid therapy.28

Chinese Red Yeast Rice

Eighty-three healthy subjects (46 men and 37 women aged 34-78 y) with hyperlipidemia [total cholesterol, 5.28-8.74 mmol/L (204-338 mg/dL); LDL cholesterol, 3.31-7.16 mmol/L (128-277 mg/dL); triacylglycerol, 0.62-2.78 mmol/L (55-246 mg/dL); and HDL cholesterol 0.78-2.46 mmol/L (30-95 mg/dL)] who were not being treated with lipid-lowering drugs participated. Subjects were treated with red yeast rice (2.4 g/d) or placebo and instructed to consume a diet providing 30% of energy from fat, 10% from saturated fat, and 300 mg cholesterol daily. Red yeast rice significantly reduces total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and total triacylglycerol concentrations compared with placebo and provides a new, novel, food-based approach to lowering cholesterol in the general population.29

1. Fried LP, Kronmal RA, Newman AB, et al. Risk factors for 5-year mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study [see comments]. Jama 1998;279(8):585-92. 2. Weverling-Rijnsburger AW, Blauw GJ, Lagaay AM, Knook DL, Meinders AE, Westendorp RG. Total cholesterol and risk of mortality in the oldest old [published erratum appears in Lancet 1998 Jan 3;351(9095):70] [see comments]. Lancet 1997;350(9085):1119-23. 3. Bucher HC, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH. Systematic review on the risk and benefit of different cholesterol- lowering interventions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19(2):187-95. 4. Hebert PR, Gaziano JM, Chan KS, Hennekens CH. Cholesterol lowering with statin drugs, risk of stroke, and total mortality. An overview of randomized trials [see comments]. Jama 1997;278(4):313-21. 5. Roche HM, Zampelas A, Knapper JM, et al. Effect of long-term olive oil dietary intervention on postprandial triacylglycerol and factor VII metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68(3):552-60. 6. Albert CM, Hennekens CH, O'Donnell CJ, et al. Fish consumption and risk of sudden cardiac death [see comments]. Jama 1998;279(1):23-8.

8 Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program

7. Subbaiah PV, Subramanian VS, Liu M. Trans unsaturated fatty acids inhibit lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase and alter its positional specificity. J Lipid Res 1998;39(7):1438-47. 8. Maislos M, Abou-Rabiah Y, Zuili I, Iordash S, Shany S. Gorging and plasma HDL-cholesterol--the Ramadan model. Eur J Clin Nutr 1998;52(2):127-30. 9. Nagata C, Takatsuka N, Kurisu Y, Shimizu H. Decreased serum total cholesterol concentration is associated with high intake of soy products in Japanese men and women. J Nutr 1998;128(2):209- 13. 10. Wong WW, Smith EO, Stuff JE, Hachey DL, Heird WC, Pownell HJ. Cholesterol-lowering effect of soy protein in normocholesterolemic and hypercholesterolemic men. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68(6 Suppl):1385S-1389S. 11. Duane WC. Effects of soybean protein and very low dietary cholesterol on serum lipids, biliary lipids, and fecal sterols in humans. Metabolism 1999;48(4):489-94. 12. Taylor LM, Jr., Moneta GL, Sexton GJ, Schuff RA, Porter JM. Prospective blinded study of the relationship between plasma homocysteine and progression of symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 1999;29(1):8-19; discussion 19-21. 13. Stephens NG, Parsons A, Schofield PM, Kelly F, Cheeseman K, Mitchinson MJ. Randomised controlled trial of vitamin E in patients with coronary disease: Cambridge Heart Antioxidant Study (CHAOS) [see comments]. Lancet 1996;347(9004):781-6. 14. Pearce BC, Parker RA, Deason ME, Qureshi AA, Wright JJ. Hypocholesterolemic activity of synthetic and natural tocotrienols. J Med Chem 1992;35(20):3595-606. 15. Liao F, Folsom AR, Brancati FL. Is low magnesium concentration a risk factor for coronary heart disease? The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J 1998;136(3):480- 90. 16. Klevay LM. Lack of a recommended dietary allowance for copper may be hazardous to your health. J Am Coll Nutr 1998;17(4):322-6. 17. Jones AA, DiSilvestro RA, Coleman M, Wagner TL. Copper supplementation of adult men: effects on blood copper enzyme activities and indicators of cardiovascular disease risk. Metabolism 1997;46(12):1380-3. 18. Lee TS, Shiao MS, Pan CC, Chau LY. Iron-deficient diet reduces atherosclerotic lesions in apoE- deficient mice. Circulation 1999;99(9):1222-9. 19. Stefanutti C, Vivenzio A, Lucani G, Di Giacomo S, Lucani E. Effect of L-carnitine on plasma lipoprotein fatty acids pattern in patients with primary hyperlipoproteinemia. Clin Ter 1998;149(2):115-9. 20. Mondola P, Santillo M, De Mercato R, Santangelo F. The effect of L-carnitine on cholesterol metabolism in rat (Rattus bubalus) hepatocyte cells. Int J Biochem 1992;24(7):1047-50. 21. Mortensen SA, Leth A, Agner E, Rohde M. Dose-related decrease of serum coenzyme Q10 during treatment with HMG- CoA reductase inhibitors. Mol Aspects Med 1997;18(Suppl):S137-44. 22. Park T, Lee K. Dietary taurine supplementation reduces plasma and liver cholesterol and triglyceride levels in rats fed a high-cholesterol or a cholesterol- free diet. Adv Exp Med Biol 1998;442:319-25. 23. Ishikawa T, Fujiyama Y, Igarashi O, et al. Effects of gammalinolenic acid on plasma lipoproteins and apolipoproteins. Atherosclerosis 1989;75(2-3):95-104. 24. Horrobin DF. Loss of delta-6-desaturase activity as a key factor in aging. Med Hypotheses 1981;7(9):1211-20. 25. Lee KN, Kritchevsky D, Pariza MW. Conjugated linoleic acid and atherosclerosis in rabbits. Atherosclerosis 1994;108(1):19-25.

9 Program AT Atherosclerosis Prevention Program

26. Truitt A, McNeill G, Vanderhoek JY. Antiplatelet effects of conjugated linoleic acid isomers. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999;1438(2):239-246. 27. Singh RB, Niaz MA, Ghosh S. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of Commiphora mukul as an adjunct to dietary therapy in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1994;8(4):659-64. 28. Nityanand S, Srivastava JS, Asthana OP. Clinical trials with gugulipid. A new hypolipidaemic agent [see comments]. J Assoc Physicians India 1989;37(5):323-8. 29. Heber D, Yip I, Ashley JM, Elashoff DA, Elashoff RM, Go VL. Cholesterol-lowering effects of a proprietary Chinese red-yeast-rice dietary supplement. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69(2):231-6.

10