Economic Contexts for Renaissance Areas of Study

The following article is an attempt to provide teachers with some information about the economic circumstances of Europe between 1300 and the sixteenth century.

Trading Networks

One of the major myths is the idea that travel was limited in this period and that many of the states studied in Renaissance Areas of Study were isolated and that contact with other areas of the world was limited. However, as Evelyn Welch says on page 16 of Art in Renaissance Italy, “nevertheless what prevented the peninsula from becoming a series of isolated, independent fragments was the facility and ease with which men, women, and objects travelled.” The fact that a trader was often nothing more “than a peddler plodding dusty roads by the side of the Rhone, carrying his pack laden with eastern marvels to the rural fairs of Champagne” indicates how ready people were to walk vast distances when necessary. (J. Plumb, The Pelican Book of the Renaissance, pg 19.

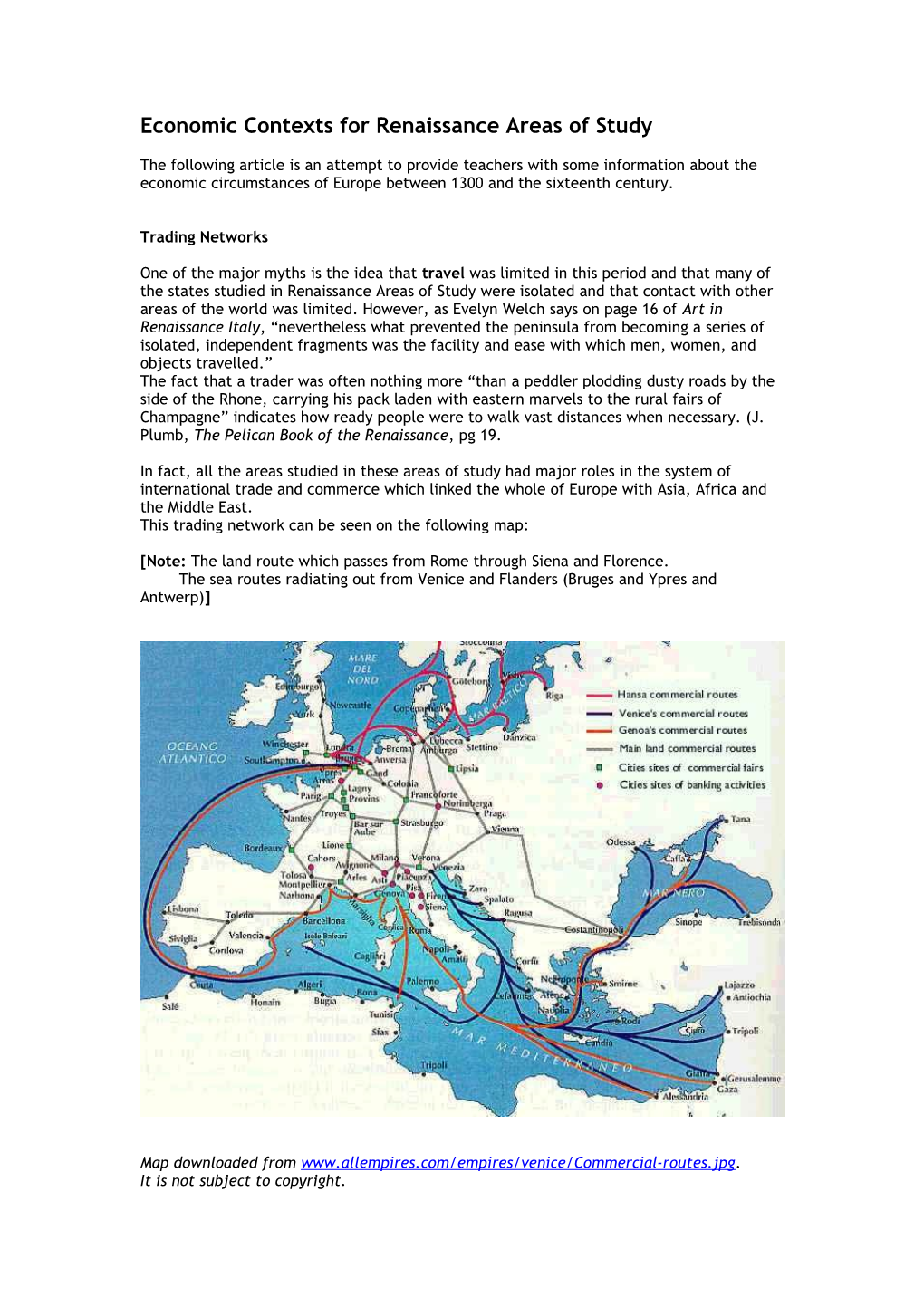

In fact, all the areas studied in these areas of study had major roles in the system of international trade and commerce which linked the whole of Europe with Asia, Africa and the Middle East. This trading network can be seen on the following map:

[Note: The land route which passes from Rome through Siena and Florence. The sea routes radiating out from Venice and Flanders (Bruges and Ypres and Antwerp)]

Map downloaded from www.allempires.com/empires/venice/Commercial-routes.jpg. It is not subject to copyright. These routes were also used for pilgrimage. All Christians tried to make a pilgrimage during their lifetime in search of healing, forgiveness and miracles. The poor travelled short distances, to local churches and shrines (think of Chaucer’s group of pilgrims in his Canterbury Tales) while pilgrimage for the nobility often meant international travel. In the fourteenth and fifteenth century wealthy pilgrims went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem in organised groups. The Crusades are a related example of international expeditions which covered great distances.

These routes were also used for the movement of armies during wartime. The common vocation of mercenary soldiers created a large international population of professional soldiers.

Trade

The invention of the maritime compass in the 1290s contributed to a rapid increase in shipping and led to the growth of the large mercantile navies which made city states like Genoa, Venice and Flanders wealthy. By the fifteenth century Italy had become a trading centre for all of Europe and the increasing wealth of Italian merchants and traders was threatening established systems of wealth and social and political order. In the eleventh century Venetian merchants were given special privileges which enabled them to travel freely throughout Byzantine territories. In the first half of the 14th century there were Italian merchant colonies in China, including several Bishops. The Sienese Bonsignori family and the Florentine Peruzzi and Bardi families were bankers to the English King Edward III. Italian traders are recorded in the North of England sourcing English wool in the fifteenth century. Traders from all over the world, including Italy, came to the Flemish Cloth Exchanges in Bruges and Ypres. Italian mercantile families, like the Arnolfini, settled in these lucrative market towns.

Traded Goods:

Lists of goods which were traded give a good indication of the widespread nature of these trading networks: (Much of this information was gathered from: www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/nistory/middleages/trade.html )

From Africa came slaves; sugar; gold; ivory; precious stones; From Asia – silk; carpets; furs; spices, porcelain (many of these were traded in the Middle East from Asian traders on the Silk Road) From the Holy Land – rice; cotton; perfume; mirrors; lemons; melons From Northern Europe: grain; salt; wool; copper; fish and timber were processed and traded. Glass was an important commodity, firstly from Baghdad, and then from Venice once that city’s glass manufacturers developed a monopoly trade over the best sources of soda used in its production. English wool was traded in the cloth towns of Flanders – Bruges, Lille. etc Cloth making workshops in Flanders also lace, tapestry, In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the Burgundian courts in Bruges, Lille and Brussels set the fashions for aristocratic Europe with clothing and tapestries which they produced for many European courts. England imported tar, timber, furs, and rope from the Baltic; cloth and lace from Flanders and glass from the Mediterranean. Other items included in cargo lists are rhubarb; mummy dust (used to make brown pigments); tamarinds; turpentine. Other English exports included wool; fish; metal and honey Western goods which were exported to the East included wood, steel and weapons which were exchanged for spices – pepper, ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg. silk, cochineal and indigo, cotton, drugs and sugar. Moroccan leather, Islamic swords; Persian carpets; Syrian damask; Egyptian cotton. Slaves were traded from Africa and Asia and the Crimea. The Crusades stimulated trade by opening up Eastern markets to supply lemons; apricots; sugar and Egyptian cotton.

Colours:

In Victoria Finlay’s book Colour, Sceptre, London, 2002, the origins of many of the pigments used in painting are discussed. The sources she identifies indicate the high dependence of painters on international trade. Ochre – Tuscany, especially Siena, the Luberon in France Graphite from Borrowdale (UK) recorded as being sent to an art school in Italy in 1564 (pg 96) Mummy brown from Egypt (a pigment made from the dust of mummies!) Indian ink from China Alum - the main alum market was in Champagne. It came from Aleppo in the East and Castile in the west but a huge source was discovered in Tolfa near Rome in 1458 and the Vatican developed a major trade in it Gums and resins for mixing from Chios and the markets of Northern Africa Turpentine made from larches purchased at Venetian markets Amber form the Baltic Indigo from India Purple from the Middle East Ultramarine from lapis lazuli from Afghanistan

Relics

There was a thriving trade in holy relics which is related to the lucrative pilgrimage traffic. Possession of a rare relic would entice pilgrims to a church which was obviously good for business. Often these were stolen in missions sanctioned by governments e.g. the expedition from the Italian town of Bari to the Turkish town of Myra to obtain the relics of St Nicolas. It was successful.

The Hansa League:

The German Hansa League was a powerful organisation of merchants and traders which was concentrated in the Baltic region trading from Novgorod in Russia, through Poland, Scandinavia and Germany itself. It was founded in the middle of the twelfth century and lasted 300 years. Traded materials – agricultural products; raw materials for shipping – grain; The league controlled trade within their boundaries with tariffs.

Fairs

While the great Exchanges controlled the large scale trade of merchants, international fairs were important for the sale of goods among private individuals and small merchants. Great international fairs at Geneva; Lyon; Medina, Frankfurt; Bruges; Champagne. The fairs in the Champagne area operated all year round.

Banking Increasing trade networks led to the development of new financial systems which would assist merchants in their travels and trade. All the great trading towns and cities had Exchanges representing the major trading nations, such as Italian credit exchanges at the Champagne fairs. The Exchanges changed currency and issued bills of exchange which were recognised internationally. Many of the major mercantile families got into banking because they need to operate Exchanges. In the thirteenth century many great banking innovations were made by Italian merchants who set up trading banks eg: account books with Arabic numbers; double entry bookkeeping; marine insurance; bills of landing; bills of exchange; promissory notes. Banks also accepted money to be held in deposit. In the 1520’s, the interest to be paid on deposits in Flemish banks had been fixed at 12% by decree of the Emperor Charles V and confirmed by his successor Philip. The role of Papal Banker gave a bank a huge financial advantage because in their role of banking agent to papacy the bank had the right to collect papal tithes and hold them until they were needed. While holding these funds the bank was entitled to use them in the form of loans. By the end of the fourteenth century the Florentine Acciaiouli family’s bank had 53 branches throughout Europe while another Florentine family, the Peruzzi had 83 branches.

Diplomacy

The Italians are credited with the development of official diplomacy by sending ambassadors to look after the interests of their merchants in the main cities of their trading partners. The first states to establish resident ambassadors were Mantua and |Milan however it was Venice which gained greatest recognition for the extent and influence of its diplomatic network.

The Social Position of the Merchant.

In Medieval society the merchant class was often criticised by the clergy because of their profiteering. Merchants were regarded with suspicion by the traditional aristocracy who believed in the primacy of property and wealth earned from the land. Increasing trade encouraged the merchant class to value education because of a need for knowledge and language in different parts of the world and the need to record transactions. This challenged the traditional domination on education by the aristocracy and the church. The aristocrats did not vanish; they lived on providing a snobbish goal to which the wealthy merchant might aspire. The rich merchants of Italy had become some of the major power brokers of the world and they wanted to be seen as such. This is one of the reasons for their conspicuous consumption. Commercial capitalism was expressed in the patronage of education and the arts. Architects and artists were employed to create environments befitting the new princes of mercantilism. Artists were also employed to record accumulated wealth – the imported furs and precious jewels worn in portraits, glimpses of opulent interiors and estates and villas which are slipped into paintings. Merchants demonstrated their wealth with commissions to decorate public places and atoned for their profits by spending a proportion annually on church building and decoration. It was customary to leave a financial legacy to a church or monastic order to provide for buildings and art works. Artisans and merchants were organised into guilds and by the thirteenth century these rich and influential groups had become the most important organisations in Italian city states with the ability to control industry, trade and foreign exchange. They were also important art patrons whose rivalry was expressed in competing art projects.

Siena Siena’s location astride the Via Francigena, the main road from Rome to the North – the only city between Lucca and Viterbo – encouraged the development of lucrative markets selling agricultural goods to the many travelling traders and pilgrims who passed through the city. It also led to the development of Exchanges and banks along the Via Francigena and the Campo. During the Avignon papacy, traffic through Siena increased because of its position on the main Italian road to Avignon.

Sienese wealth arose from its fertile agricultural soil and production of surpluses and the large silver mines in its territory.

In 1200 the most important families of the city and the Papal bankers started banking activity in the city. The city of Siena was given its full independence by Frederick Barbarossa who in 1180 acknowledged the right of bartering money. This decree gave Siena an early lead in the development of trading banks. The Gran Tavola was a group of Sienese bankers who lent money to the pope and cardinals in this period. The Tolomei was another Sienese family bank which looked after the pope’s affairs By the beginning of the fourteenth century most important Sienese families were engaged in banking and several had contracts with the papacy which gave them the right to act as papal agents internationally. In the mid thirteenth century two brothers, Orlando and Bonifazi, Buonsignori established a money lending business in Siena. By the late thirteenth century they were rumoured to be insolvent and Philip the Fair of France confiscated the assets of all Sienese merchants in France. For the next forty years papal agents were still trying to retrieve their money. The Buonsignori recovered, however a set back occurred in 1342 when King Edward III of England reneged on his Italian loans and confiscated the goods of these banks in England. This led to the collapse of the Sienese Buonsignori family and to the collapse of the Florentine Bardi and Peruzzi banks. This financial setback coincided with the onset of the severe outbreak of plague which decimated the Sienese population.

The immense wealth of Siena is evidenced in the huge building boom which took place in the fourteenth century and the commissioning of significant large works of art in the last third of the thirteenth century and the first half of the fourteenth century.

The Sienese were well known for their love of rich clothes, especially gold trimmed brocade. This Sienese fashion continued well into the fifteenth century when imported cloth from Flanders, finely woven in plain colours came into fashion in Italy. The Sienese love of expensive cloth of gold is well-illustrated in the following anecdote:

“There was a Sienese ambassador in Naples who was, as the Sienese tend to be very grand. Now King Alfonso usually dressed in black, with just a buckle in his cap and a gold chain around his neck; he did not use brocades or silk clothes much. This ambassador however dressed in gold brocade, very rich, and when he came to see the King he always wore this gold brocade. Among his own people the King often made fun of these brocade clothes. On day he said, laughing to one of his gentlemen, “I think we should change the colour of that brocade.” So he arranged to give an audience one day in a mean little room summoned ambassadors, and also arranged with some of his own people that in the throng everyone should jostle the Sienese ambassador and rub against his brocade. And on the day it was so handled and rubbed, not just by the other ambassadors, but by the king himself, that when they came out of the room no-one could help laughing when they saw the brocade, because it was crimson now, with the pile all crushed and the gold fallen off it, just yellow silk left; it looked the ugliest rag in the world. When he saw him go out of the room with his brocade all ruined and messed, the king could not stop laughing…..” pg 15, M. Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, quoting from a letter by the Florentine bookseller, Vespasiano da Bisticci Important Conclusions:

While it is true to say that Siena was landlocked, she was not isolated. In fact her position on the Via Francigena placed her in the middle of the wealthy papal trading and diplomatic traffic. Travel from Siena to important local cities like Assisi and Florence was well within the reach of all but the very poor, therefore the likelihood of well qualified and paid artists making journeys to see the work of other artists is very high. Siena had similar banking and trading practices to Florence. The Sienese government was also an individual form of Republic. Therefore it is not really appropriate to describe Siena as backward or old fashioned. While Siena may have been less wealthy than Florence by the mid fourteenth century she was still a wealthy state and some of her leading families were among the wealthiest in the world. The major Sienese artists of the fourteenth century do appear to have worked for foreign patrons and most of them are reported as having journeyed to cities beyond the immediate environment of Siena.

Florence

In the early fourteenth century Florentine banks began to gain the lucrative Papal monopolies. The gold florin which was first struck in 1252 was one of the first coins to become an international standard. The Venetian ducat, first struck in 1282, became its first major rival. In 1335 Bankers were entitled to charge 8 – 10% in interest for loaned money. The development of family banks usually grew out of trading activities eg: Giovanni di Bicci de Medici was a wool trader before becoming involved in banking. The Bardi family became Papal Bankers in the fourteenth century, then the Alberti, then the Medici. They had rights to collect taxes owed to Papacy by each metropolitan province of the church throughout the Christian world. The money was deposited in their own banks and could be used by the bankers until it was called for by the Pope. (The fact that many of the main wool producers in Northern Europe were monastic ensured that the Church was one of the greatest capitalists of this period.) The immense wealth of Florence is expressed in the building programmes of the first half of the fourteenth century and throughout the fifteenth century and the huge number of art works commissioned in the city throughout this period. Although this was a prosperous period for Florence, the city’s growing strength was challenged frequently and the Florentines developed diplomatic skills to maintain their independence.

.

Venice

In 1095 Venetian merchants were granted freedom of commerce throughout Germany and Italy by the Holy Roman Emperor Venice supported the Fourth Crusade in 1202-04 to protect its Middle Eastern colonies. After the defeat of Genoa Venice had domination over Eastern trade. With key outposts in Egypt and Syria Venetian merchants connected with caravans from India. By the thirteenth century Venice had the most impressive commercial and military fleet in the Mediterranean. Venice expanded into the Italian mainland to gain more space in the fourteenth century, occupying Vicenza; Verona and Dalmatia, and, in the fifteenth century, Ravenna, Brescia and Bergamo. The Peace of Lodi between Venice and Milan in 1454 fixed their boundary. In the fifteenth century Venice began losing Eastern territory to the expansionist Ottoman Empire, which had taken Constantinople in 1453. Venice exported 25% of the silver mined in Europe. Venetians retained their power with skilful diplomacy and alliance building, exploiting their strategic geographical position, and variously allying with the papacy; France, Milan and the Hapsburgs.

Rome:

For much of the fourteenth century the popes had lived at Avignon. This attracted the great bureaucracy which had grown up around the St Peter’s in Rome and the city’s lawyer’s clerics and merchants moved to Avignon to benefit from the Papal tithes that Western Europe paid to the Papacy. Although a few cardinals remained in Rome and tried to keep the Curia functioning, the city fell into an economic recession and political anarchy. In 1417 the Great Schism was healed when the Roman Cardinal Martin V was elected Pope and returned the Papal court to Rome. He was a capable administrator and soon stabilised the city. The wealth of the papal tithes returned to Rome; pilgrims and diplomats visited again (20,000 in 1500) and monasteries expanded to house the visitors. The wealthy nobles of Europe returned to build new palaces from which they could participate in church politics. The merchants and bankers returned to supply the luxuries demanded by a string of powerful Popes who were intent on rebuilding the glory of Rome. The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were periods of extravagant architecture and town planning in Rome.

**********************************************

The following summary is taken from a book titled The Dawn of a New Era 1250-1435 written by Edward P. Cheney, the first book in the 20-volume historical series The Rise of Modern Europe. The original copyright was in 1936; this particular copy is dated 1971, so the monetary figures in “modern value” are not accurate.

Chapter Two: Merchant Princes and Bankers

Merchant Moneylenders:

Capitalism entered into the life of Europe earlier than is commonly realized. Large-scale manufacturing was seen, especially in Italian and Flemish cities. Merchants and manufacturers were also the moneylenders, generating more money for them. In earlier times successful merchants invested their money in landed property in growing towns and became a patrician class living on their rents and on the gains of civil office. Eventually trade and banking became separate.

Tiedemann of Limburg was a German who traded goods with England, where he acquired wool and other products. He had a membership in the Steelyard and house on Thames Street in England, where he stayed from 1346 to 1360 and became wealthy. He and other Germans lent money to English nobles, citizens and even to the crown. He farmed certain of the taxes and took over the administration of the royal tin mines. Tiedemann had a home in Cologne and ran a wholesale wine business. He became the wealthiest property holder in that town and also had land in Andernach. Nicholas Bartholomew of Lucca was a contemporary of Tiedemann. He also lived in London, exporting wool in exchange for silk and other products. He was fined for smuggling and brought antagonism from native English mercers. He also loaned money to English monarchy.

Successive mayors of London, like Sir John Pultney, the cloth merchant who was mayor four times between 1331 and 1337, advanced money to the king. By way of compensation Pultney was allowed to export wool during an embargo without paying duty. He acquired much landed property in both the city and county and built a magnificent house.

Later in the 14th century Sir John Philpot, an importer of spices, sugar and other items lent to the king the equivalent of half a million dollars and to fit out at his own expense a squadron with 1,000 men to drive a predatory French fleet away from the English shore.

The Bankers:

There was also a class of genuine bankers. Modern banking is a result of four roots: from the excess profits of trade; from the business of money-changers who bartered coin of one country for that of another; from the transfer for a consideration of money from place to place or it’s safe-keeping; from the needs of kings, popes and others for money.

In England foreign merchants acted as moneychangers under royal license. At every fair and every point of international trade the establishments of moneychangers existed. The Taula di Cambi at Barcelona was the first bank of deposit in Europe. The Gran Tavola was a group of Sienese bankers who lent money to the pope, to cardinals and others throughout Europe. Italy was the prominent location for banking, due to its history, early economic development and the papal court at Rome. The pope had claim to Peter’s pence, annates and numerous other payments, all secured by bankers.

In the mid 13th century two brothers, Orlando and Bonifazio Buonsignori, established a money-lending business at Siena. They became regular bankers to the Holy See and six popes. In late 13th century there were rumours of their insolvency, they claimed that all their creditors sought reimbursement at the same time. With frozen assets and unavailable funds they sought help from Pope Boniface VIII, but in 1307 they closed their doors. Philip the Fair of France claimed that the agents of the Buonsignori had fled from France owning him money and, according to the practice of the time, seized the property of all Sienese merchants in France to make up for his losses. For the next forty years papal officials were still trying to close out their accounts, and the grabbing of the money by Philip was a disaster for the city of Siena.

The Buonsignori was one of many banking firms that tended to the pope’s financial affairs. The Tolomei (of Siena), the Ricciardi (Lucca), the Chiarenti and Ammanati (both of Pistoia) and a group of Florentine bankers also worked for the pope. In 1277 Pope Nicholas II borrowed 200,000 gold florins from Piotoian and Florentine bankers for the expedition of Rudolph II of Hapsburg against Ottokar of Bohemia, which led to victory for Rudolph and the establishment of the House of Hapsburg in the Austrian dominions. During the later 13th century Rome teemed with representatives of financial firms, at least twenty were named in the papal registers. Most were family businesses, although some banks combined the capital of several families and took the name of the most prominent or oldest constituent of the group.

Florence as a Banking City:

Florence excelled all other Italian cites as a money market. First wealthy from wool, banking became its principal avocation. Its banking families were many: the Mozzi, Peruzzi, Bardi, Cerci, Falconers, Alfani and the Alfani to name a few. Collection of Papal dues: The house of Spini was in charge of the collections from Germany; the Alfani in Hungary, Poland, Slavonia, Norway and Sweden; the Chiarenti in Spain, and six other companies in England. The Templar Knights were often assigned with the conveyance of the money, whether it be the papal dues, or riches of kings and other wealthy people.

Kings during times of war needed large sums of money immediately, and the bankers made much profit from these situations. In about the year 1290 three brothers, Muschiato, Biccio, and Niccolo Guidi left Florence for France to enter in the service of Philip the Fair. The eldest brother became the receiver of taxes and treasurer and all three acted as financial agents. They provided Philip money for the bribing of the Duke of Brabant and the Count of Holland to end their alliance with England. They were able to seize money deposited in two abbeys by the Bishop of Winchester and hired mercenaries used in the attack on Pope Boniface at Angani. They also assisted in the seizure of the treasures of the Templars.

Not all banking families were successful. By the early 14th century eighteen banking houses either failed or were absorbed by others. The Bardi and Peruzzi remained in England. The Peruzzi had agencies in sixteen cites in five countries. Representing the Bardi family was the father of novelist Giovanni Boccaccio.

In order for Edward III to finance his war against France he needed to borrow money from many sources all at interest and used his crown as a pledge and the queen’s crown as security. The crown jewels were also pawned off.

When the Hundred Years War began the bankers had made loans to both the Kings of France and England and also had deposits in both kingdoms. In 1338 Philip seized the property of the banker’s agents, suspecting them of being impartial towards England. The property was returned after large payments were made.

Since the debts were not always paid some banks failed. The king of Naples could not repay a debt and the Peruzzi failed in 1343. The Bardi followed the next year when Edward was not able to meet his payments, estimated to be about eight million dollars in modern value. Edward was loaned about twenty million dollars total and by 1391 the account was settled. After the Italian bankers failed the monarchs turned to German merchants and lesser Italian banks for loans. They also relied on their own nation’s capitalists for financial aid as well as towns, ecclesiastical bodies, noblemen and the gentry, leading to the increase of nationalism.

The Origin of Modern Banking:

When the principal Florentine companies failed in the mid 14th century the obscure Medici family survived, led by Giovanni de Medici and his sons Lorenzo and Cosimo. In Augsburg, in the year 1409, Jakob Fugger, a merchant’s son, became a banker. When he died fifty years later the business he left to his seven sons was one of the most powerful ever. Although private banking houses continued the modern form of the government-chartered bank began. Along with the merchant bankers were others who loaned money who were known as banchier.

The Influence of Coined Money:

Gold and silver were mined throughout Europe: Italy, southern France, Spain, Germany, Silesia, Austria, Hungary, Bohemia and England all had mines. In times of crisis holders of gold and silver plate were required to dispose a certain proportion of it at the mint for converting into coinage. England and other countries without a vast amount of native supply of the precious metals had to import bars. They would sometimes seize and re-coin money from other countries and forbade the export of their own coins. Foreign money was usually paid for by the export of goods, not in coin. In England all mints belonged to the government, though frequently sublet. In France 29 feudal lords had the right to coin money, in addition to the royal mints. Some cities also coined their own money. Up to the mid 13th century the money of Western Europe had been exclusively of silver. Within a half century gold was adopted for coinage in a dozen different states. In 1252 Florence began the issue of its gold florins. In 1257 Henry III coined a gold penny, twice the weight of and twenty times the value of the silver penny. The Venetian ducat appeared in 1284 and after that Philip the Fair minted gold coins in France. By the mid 14th century the English noble was in common use and various other gold coins were being issued.

The most prominent of these gold coins were the florins; its use was widespread throughout Europe. Soon many sovereigns and cities were minting coins of the same name and of nearly the same value. The English gold pennies were not popular and not long in use. The next generation of gold coins in 1344 were originally called florins; though double the weight of the original. The size increased again and the name was changed to nobles, the English gold coin for the next century. The Florentine minters were so respected that they were in charge of the mints of other countries. The ducat had the same reputation, although its circulation was eastward, in Italy, the Mediterranean, and the Orient.

Examples of contracts: A one pound partnership between a priest and a traveller for a journey to Acre in Syria A 6500 pound contract between the Spinola and Cibo clans to buy land in Sicily 1377