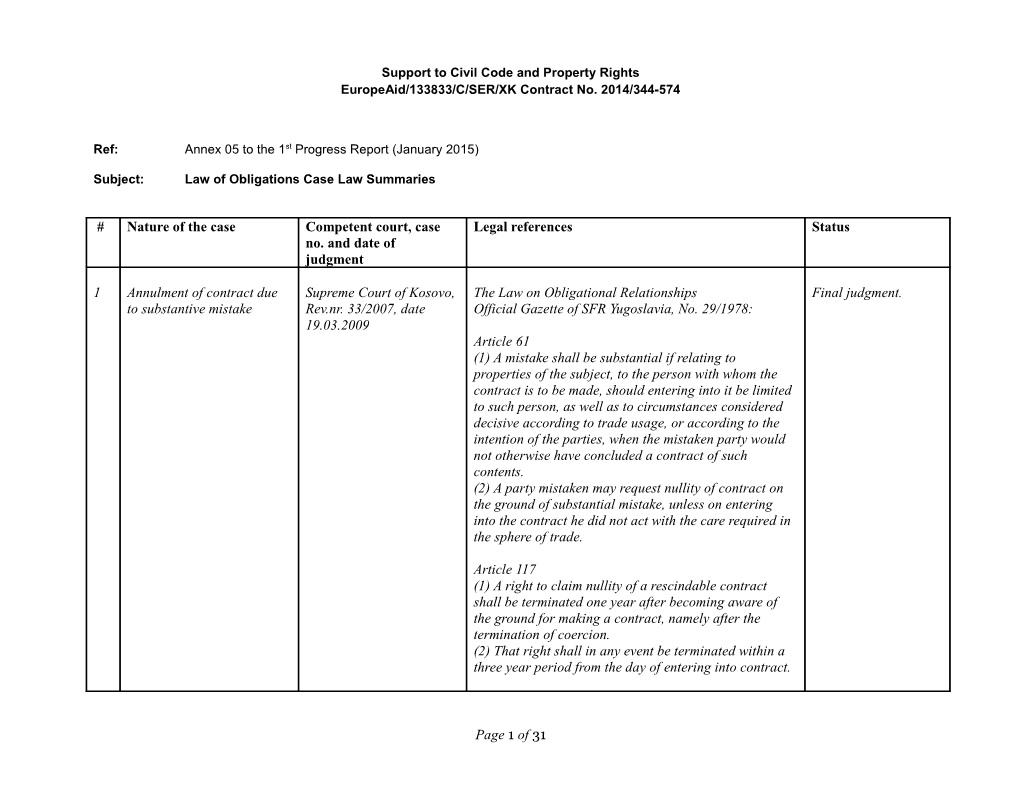

Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

# Nature of the case Competent court, case Legal references Status no. and date of judgment

1 Annulment of contract due Supreme Court of Kosovo, The Law on Obligational Relationships Final judgment. to substantive mistake Rev.nr. 33/2007, date Official Gazette of SFR Yugoslavia, No. 29/1978: 19.03.2009 Article 61 (1) A mistake shall be substantial if relating to properties of the subject, to the person with whom the contract is to be made, should entering into it be limited to such person, as well as to circumstances considered decisive according to trade usage, or according to the intention of the parties, when the mistaken party would not otherwise have concluded a contract of such contents. (2) A party mistaken may request nullity of contract on the ground of substantial mistake, unless on entering into the contract he did not act with the care required in the sphere of trade.

Article 117 (1) A right to claim nullity of a rescindable contract shall be terminated one year after becoming aware of the ground for making a contract, namely after the termination of coercion. (2) That right shall in any event be terminated within a three year period from the day of entering into contract.

Page 1 of 31 Cf. Article 46 and Article 102 of the Law of Obligational Relationships, O.G. of the R. of Kosovo nr. 16/2012), date 19.06.2012:

Article 46 (1) A mistake shall be deemed significant if it relates to the essential characteristics of the subject, to a person with whom a contract is being concluded if it is being concluded in respect of such person, or to circumstances that according to the custom in the transaction or according to the intention of the parties are deemed to be decisive, as otherwise the mistaken party would not have concluded the contract with such content. (2) The mistaken party may request the annulment of the contract for reason of a significant mistake, unless in concluding the contract the party failed to act with the diligence required in the transaction. (3) If a contract is annulled for reason of a mistake the party that acted in good faith shall have the right to demand reimbursement for damage incurred for this reason. (4) The mistaken party may not make reference to the mistake if the other party is prepared to perform the contract as if there had been no mistake.

Article 102 (1) The right to request the annulment of a challengeable contract shall expire one year from the day the entitled person learnt of the grounds for challengeability, or one (1) year after the end of duress. (2) In any case this right shall expire three (3) years after the day the contract was concluded.

Facts of the case

The Plaintiff, a juvenile represented by his father as legal representative, concluded with the Defendant (physical person) two contracts in 2001 Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

(respectively, no. 425/01 and 502/8) “for merger of funds for the construction of buildings” in the amount of 43.900 EUR. As an advance payment, the Plaintiff (investor/purchaser) paid to the Defendant (property owner/developer) the amount of 27.850 EUR as compensation in exchange for building two business premises on the Defendant’s land plot specified in the above-mentioned contracts. Both contracts were signed by the parties but were not verified in the court.

The disputed contracts referred in Clause 1 to a construction permit allegedly issued on 23.02.2001. However, after the conclusion of the two contracts the Plaintiff found out from the Directorate for urban planning that no construction permit had been issued for the construction of business premises on the land plot specified in the disputed contracts. As it turned out, the number of the permit shown in the disputed contracts was not the serial number for a construction permit; rather, it was the number of the “urban consent” (which only confirmed the status of construction land without implying any right to build). As a result, the Plaintiff was led into error with regard to the existence of a construction permit.

Soon after having been informed about the lack of a construction permit, the Plaintiff filed a lawsuit in the Municipal Court of Peja, claiming the annulment of both contracts and the repayment of the amount of money paid in advance. The court of first instance found that the Plaintiff had incurred a “substantial error” as foreseen in Article 61 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978). However, the court of first instance concluded that the claim was unfounded on the grounds of Article 117.1 of the same law, which provides that the right to request the annulment of a contract expires after one year from the day the party becomes aware of the grounds for annulment.

On 10.10.2006, the District Court of Peja confirmed that the court of first instance had correctly applied the material law when deciding in favour of the Defendant. In the opinion of the court, the annulment of the disputed contracts should have been sought within the “relative” and “absolute” limitation periods set forth in Article 117 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978). Since the claim was submitted after the above- mentioned periods had elapsed, the Municipal Court of Peja rightly decided to reject the claim as ungrounded.

Thereafter, the Plaintiff exercised an extraordinary legal remedy by submitting a request for revision to the Supreme Court. The Court found that both courts of first and second instance had wrongly applied the material law when determining that the claim of the Plaintiff was ungrounded.

The Court maintained that the Plaintiff was misinformed about the construction permit (which had not been issued) due to the fact that the disputed contracts provided the number of the urban consent as if it were the number of the construction permit. In this way, the Defendant induced the Plaintiff in substantial mistake within the meaning of Article 61 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), since the Plaintiff would have never given his consent to the disputed contracts if he would have been not misled by the Defendant’s misrepresentation of facts.

Page 3 of 31 The Court further argued that the lower instance courts had wrongly applied the provisions of Article 117(1) of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978) regarding the periods of limitation. According to the Court, the Plaintiff was informed by the Directorate of urban planning that there was an urban consent but no construction permit on 09.10.2003, whereas the claim for annulment of contract was lodged on 23.01.2004. Therefore, the Court concluded that the 1-year period of limitation for seeking annulment of contract had not expired yet.

Legal issue/s

This judgment concerns the question whether the circumstance that a construction permit – which the parties to a contract of merger of funds for the construction of buildings have erroneously regarded existing at the time of conclusion of the contract – can be considered a “substantial mistake” within the meaning of Article 61 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), and may therefore be invoked as a ground for annulment of the contract. The judgment also concerns the question whether the limitation period of one year foreseen in Article 117(1) of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978) starts running from the date of conclusion of the contract or from the date when the party which incurred into substantial mistake became aware of the grounds for annulment of the contract.

Abstract of judgment (general rule or principle of law)

The circumstance that the parties to a contract of merger of funds for the construction of buildings have erroneously regarded a construction permit as existing at the time of conclusion of the contract (as specified in the contract itself) may be considered a “substantial mistake” within the meaning of Article 61 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), and may therefore be invoked as a ground for annulment of the contract. The limitation period of one year foreseen in Article 117(1) of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978) starts running from the date when the party which was induced into mistake is informed by the Directorate for urban planning of the non-existence of the construction permit referred to in the contract.

If relevant – comments

This judgment is still relevant since Articles 46 and 102 of new Law on Obligational Relationships (2012) mostly reiterate the same provisions previously foreseen in Articles 61 and 117 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978).

# Nature of the case Co Legal references Status mp ete nt cou Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

rt, cas e no. an d dat e of jud gm ent

2 Contract for the transfer of immovable property / Su The Law on Obligational Relationships Final judgment. Validity of contract lacking the required “form”, pre Official Gazette of SFR Yugoslavia, No. 29/1978 i.e. court certification. me Co Article 73 urt A contract whose conclusion is made dependent on the of written form shall be considered valid although not Ko entered into such form, after contracting parties have sov performed, entirely or substantially, the obligations o – arising from such contract, unless something else Re obviously results from the purpose of prescribing the v. form. nr. 58/ Cf. Article 46 and Article 102 of the Law of Obligational 20 Relationships, O.G. of the R. of Kosovo nr. 16/2012), 07, date 19.06.2012: dat

Page 5 of 31 e Article 58 15. A contract for which the written form is required shall 03. be valid even if not concluded in this form if the 20 contracting parties fully or partly perform the 10 obligations arising there from, unless it clearly follows otherwise from the purpose for which the form was prescribed.

Facts of the case

In 1994 the Plaintiff, a private individual, purchased agricultural land from another private individual, the Defendant, for a total price of 19,558 DM. Pursuant to the sale-purchase contract, which was not certified in the court, the Plaintiff paid the price to the Defendant immediately upon signing the contract and entering into actual possession of such immovable property.

In 2005, the Plaintiff filed a claim in the Municipal Court of Gjilan, seeking recognition of his alleged ownership right over the immovable property for the purpose of registration in the cadaster. The Defendant objected that the purchase contract was not valid since it had not been certified by the court, and thus no ownership right was transferred to the Plaintiff. The court accepted the Plaintiff’s claim as founded, arguing that the Plaintiff owned the disputed land based on a valid contract, which the Defendant challenged without any ground.

The Defendant appealed the first-instance decision in the District Court of Gjilan, arguing that the contract was not valid as it lacked the form required by law, considering the fact that it had not been validly certified by the court. Accordingly, the Defendant contended that the Municipal Court of Gjilan had wrongly applied the material law. The court of second instance determined that in 1994 the Plaintiff had acquired ownership and possession over the disputed property, which he used without any solution of continuity until 2003. The court, therefore, confirmed that the Plaintiff had proven his ownership right to the disputed property and that the Defendant contested this right unreasonably.

Thereafter, the Defendant exercised an extraordinary legal remedy in the Supreme Court of Kosovo. However, the request for revision was rejected by the Court as unfounded. In its ruling, the court referred to Article 73 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), arguing that this provision is also applicable to contracts for the transfer of immovable property. According to this provision, a contract shall be valid, even where it lacks the required written form, if the contracting parties have performed, entirely or in substantial part, the obligations arising from the contract. As a result, a property transfer agreement must be deemed valid – in the opinion of the Supreme Court – where the obligations arising therefrom have been fully or substantially performed, even though the contract was not certified in the competent court as prescribed by the law. The court added that Article 73 shall be applicable to contracts for the transfer of immovable property on condition that the law does not provide otherwise and the contract does not infringe social interests. Legal issue/s

The judgment concerns the question whether the (written) contract for the transfer of immovable property lacking the required “form” (i.e. not being Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries certified in the court) may be considered valid under Article 73 of the SFRY Law on Obligations (1978), where both parties fully or substantially performed their contractual obligations.

Abstract of judgment (general rule or principle of law)

In accordance with Article 73 of the SFRY Law on Obligations (1978), the (written) contract for the transfer of immovable property shall be deemed valid if the obligations arising therefrom have been entirely or substantially performed, even though the contract was not certified in the competent court as prescribed by the law, on condition that the law does not provide otherwise and the contract does not infringe social interests.

If relevant – comments

This case is interesting because it recognises an ownership right over real estate that has been transferred pursuant to a sale-purchase contract which lacks a procedural formality, i.e. not duly certified by the competent authority (i.e. court) in accordance with Article 33 of the SFYR Law on Basic Property Relations.

With this judgment, the Supreme Court sanctions the lower courts’ interpretation that the “written form” requirement referred to in Article 73 of the SFRY Law on Obligations (1978) shall mean and include the court certification procedure foreseen by the then applicable law for the transfers of immovable property rights.

One should note, however, that Article 73 specifically refers to the written form of a contract and not to any formality. Given the process by which immovable property rights were transferred at the time when the dispute occurred, three formal requirements applied for the transfer of such rights to be legally binding: (1) written contract, (2) court certification (now replaced by notarisation (see Article 30.1 of the Law on Notary), (3) and recorded in the cadaster (currently, the immovable property rights register)1. On the contrary, Article 73 applies solely to contracts whose only formal

1 Article 36 of the new Law on Property and Other Real Rights Law (No. 03/L-154) provides that: “1. The transfer of ownership of an immovable property requires a valid contract between the transferor and the transferee as a legal ground and the registration of the change of ownership in the immovable property rights register. 2. The contract for the transfer of ownership of an immovable property must be concluded in written in the presence of both parties before a competent court or a notary public.” Article 115.1 further adds that “Acquisition, variation, transfer and termination of ownership, a right of pre-emption or a limited right relating to immovable property require a legally valid contract and registration of the relevant transaction in the immovable property rights register.

Page 7 of 31 requirement is a written form. This provision can only substitute for the necessity of a written contract when the only thing required for a valid transaction is a written contract. This is not the case for immovable property transactions, where written contracts certified in courts were originally required as an essential element for cadastral registration. Therefore, the Supreme Court may have “overstretched” the meaning of the aforesaid Article 73 through an overly extensive interpretation.

The approach of the Supreme Court (and lower courts as well) may be explained by the fact that when the purchase contract was concluded in 1994, Serbian discriminatory laws were in force in Kosovo (which prevented ethnic Albanians from acquiring and registering immovable property rights); hence, the lack of the formal element of court validation does not constitute an obstacle for the purchase contract to produce legal effects. See, e.g. Municipal Court in Lipjan, C.nr. 62/2003.

However, the Supreme Court’s judgment (like the judgments of the courts of first and second instance) fails to make reference to the circumstances referred to above. This raises serious concerns since the wording of Article 73 of the SFRY Law on Obligations (1978) has remained largely unchanged in the context of the new Law on Obligational Relationships of 2012, which provides under Article 58 that “A contract for which the written form is required shall be valid even if not concluded in this form if the contracting parties fully or partly perform the obligations arising there from, unless it clearly follows otherwise from the purpose for which the form was prescribed.”

The risk that courts in Kosovo, when applying Article 58 above, may follow the same reasoning and continue to argue, despite the change of circumstances, that an immovable property transaction is valid even where not notarised, is thus significant.

# Nature of the case Competent court, case Legal references Status no. and date of judgment

3 Enforceability of claim Municipality Court in The Law of Obligational Relationships, Published in the Final judgment. related to payment of debt Ferizaj, C.nr. 179/04, date Official Gazette of the SFRY nr. 29/1978 arising from sale contract 23.03.2012 due to unexpired general Article 371. General time limit for unenforceability due statute of limitation. to statute of limitations Claims shall become unenforceable after a ten year period, unless some other unenforceability time limit is provided by law.

Cf. Article 352 of the Law of Obligational Relationships, O.G. of the R. of Kosovo nr. 16/2012), date 19.06.2012: Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

Article 352. General statute-barring period Claims shall become statute-barred after five (5) years, unless a different period is stipulated by the statute of limitations.

Facts of the case

On 08.09.1997, the Plaintiff (seller) concluded a contract for the sale of a vehicle with the Defendant (purchaser). The price was agreed in German Marks, and according to the Defendant’s claim, the amount was equal to 10,750.00 euro. However, the Defendant never paid the agreed price for the purchase of the vehicle, despite the fact that the Plaintiff repeatedly requested the payment from him.

On 04.05.2004, the Plaintiff submitted a lawsuit to the Municipality Court in Ferizaj, requesting the payment of the vehicle’s price as agreed in the sale contract. The Plaintiff claimed that he transferred the possession of the vehicle to the Defendant, whereas the Defendant did not perform his obligations under the contract, i.e. the payment of the agreed price.

The Defendant did not dispute the fact that the Plaintiff had delivered the vehicle to him, nor did he contest the amount of the debt; however, he contested the Plaintiff’s claim by arguing that that the Plaintiff had lost the right to request performance of the obligation to pay the price of the purchased vehicle due to the expiration of the period of limitation.

The Municipal Court in Ferizaj accepted the Plaintiff’s claim as grounded and ordered the Defendant to pay the debt. In the opinion of the Court, the Plaintiff’s claim was still enforceable as the ordinary limitation period of 10 years foreseen in Article 371 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978) had still not passed.

Legal issue/s

This judgment confirms the enforceability of a claim related to the payment of a debt arising from a contract of sale if the general statute of limitation has not elapsed, in accordance with Article 371 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), which provides that a claim shall become unenforceable after a ten-year period, unless a shorter statute of limitation is specifically provided by law due to the nature of the claim.

Page 9 of 31 Abstract of judgment (general rule or principle of law)

The claim related to the payment of a debt arising from a contract of sale is enforceable if the general statute of limitation of 10 years has not passed, as foreseen in Article 371 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), unless a shorter statute of limitation is specifically provided by law due to the nature of the claim.

If relevant – comments

Although this is a simple case, the underlying judgment has been selected for review with the purpose of raising awareness about certain novelties introduced by the new Law on Obligational Relationships (2012), and notably the fact that the general limitation period has been shortened from ten to five years. Article 352 provides that “Claims shall become statute-barred after five (5) years, unless a different period is stipulated by the statute of limitations.” It is arguable that a 5-year term for an ordinary statute of limitation is too short for the satisfaction of certain claims. Therefore, a debate should take place in order to determine whether in the context of the Civil Code’s codification it would be more appropriate to amend this provision and return to the old rule envisaged in the former SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), which used to provide a general statute of limitation of 10 years.

# Nature of the case Co Legal references Status mp ete nt cou rt, cas e no. and dat e of jud gm ent Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

4 Nullity of the contract of donation of immovable Sup The Law on Transfer of Real Property Final judgment. property rem Official Gazette of SAP Kosovo, No. 45/81 and 29/86: e Co Article 8 urt The contract of donation of immovable property, of concluded under pressure, violence or in other Kos circumstances where it is concluded against the free ovo will of the party, it is absolutely null and produces no , legal effect from the moment of its conclusion. Rev .nr. 144 /20 09, dat e 08. 05. 201 2 Facts of the case

The case was initiated in 2009 by the Public Prosecutor of Prizren through an action of protection of legality pursuant to Articles 251 and 217 of the Law on Contested Procedure, whereby he appealed the final judgment of the District Court of Prizren which – by confirming the judgment of the Municipal Court of Prizren – had approved the claim of the Plaintiffs (physical persons) concerning a request to annul a contract of donation of immovable property.

The predecessors of the Plaintiffs – as donor – and the Assembly of the Municipality of Prizren – as recipient – concluded a contract for the donation of privately-owned immovable property (i.e. agricultural land) back in 1958. By means of this contract, the agricultural land of the Plaintiff’s

Page 11 of 31 predecessors was transferred to the Municipality of Prizren as socially-owned property.

In 2004 the Plaintiffs lodged a claim in the Municipal Court in Prizren requesting the annulment of the donation contract and the restitution of the disputed property. The Court, based on Article 8 of the Law on Transfer of Real Property, assessed that all the conditions were met for the contract to be declared null and void, since it had been concluded under pressure and against free will, under conditions of insecurity for people and property (e.g. the owner was interrogated by the police and threatened with losing his job in case the transaction was not completed). Therefore, the Court argued that the contract did not produce any legal effect ex tunc, that is from the moment of its conclusion. The District Court of Prizren upheld the judgment of the first instance court and rejected the appeal of the Defendant.

By contrast, the Supreme Court assessed that the courts of first and second instance wrongly applied the material law when approving the claim of the Plaintiffs. In particular, the Court argued that the annulment of the contract cannot be granted on the grounds of the SFRY Law of Obligational Relationships since the latter was not applicable at the time when the disputed property was transferred (as it entered into force only in 1978) and Article 1106 of this law expressly excludes that the same law may be applied retrospectively. The Court also noted that, while it was undisputable that the predecessors of the Plaintiff entered a contract to donate their immovable property in 1958, no evidence could be found that such a contract had been concluded under pressure, or that any form of pressure had been exerted which could have seriously endangered the life of Plaintiff’s predecessors.

However, the Court argued that even assuming that such a form of pressure, violence or lack of free will occurred, all legal deadlines to claim back the disputed property had passed after the lapse of some 46 years since the donation contract would be considered been relatively null “under general rules of civil law”. According to the Court, the time limit for claiming annulment in such circumstances was one year from the day of becoming aware of the reasons giving rise to annulment (“subjective limitation period”), and in any event no longer than three years from the conclusion of the contract (“objective limitation period”).

In light of the foregoing, the Supreme Court concluded that the courts of lower instance had wrongly applied the material law. Therefore, both judgments of the Municipal and District Courts of Prizren were overruled and the original claim submitted by the Plaintiffs in first and second instance was rejected.

Legal issue/s

The judgment relates to the practice of forced donation of private immovable property often used in former Yugoslavia, and more specifically concerns the question whether a contract of donation concluded in 1958 (allegedly, against free will) may be considered absolutely null and void (tamquam non esset) pursuant to Article 8 of the Law on Transfer of Real Property, and accordingly whether the donated property may be restituted to the former owner. The judgment also addresses the question whether the same contract may be annulled on the basis of the provisions of the FSRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978). Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

Abstract of judgment (general rule or principle of law)

A contract of donation of immovable property concluded in 1958 cannot be considered absolutely null and void, and accordingly the donated property cannot restituted to the former owner, pursuant to Article 8 of the Law on Transfer of Real Property, nor can such contract be annulled on the basis of the FSRY Law on Obligational Relationships since this law entered into force in 1978 and is not applicable retrospectively. Furthermore, after some 46 years all limitation periods for claiming the nullity of a contract under “general rules of civil law” have already passed.

If relevant – comments

This case deals with a problem of a very specific nature which derives from certain practices of the socialist regime in former Yugoslavia during the 50s and 60s, when the central government started to collect private property from owners by different means. If not expropriated through nationalisation, private owners were “persuaded” to conclude contractual agreements whereby they donated their property to the State.

With this judgment, the Supreme Court rejects the idea of introducing a “restitution right” through a legal action of annulment of donation contracts that very often – if not always – were concluded against free will.

Nevertheless, the judgment’s legal reasoning raises some concerns due to the fact that (1) the Supreme Court recalls provisions of the Law on Obligational Relationships (1978) whereas the Plaintiffs claimed the annulment of the contract based on Article 8 of the Law on Transfer of Real Property, and (2) when rejecting the claim as statute-barred, the Supreme Court generically refers to limitation periods under “general rules of civil law”, without any further explanation.

See in the same sense, Supreme Court of Kosovo – Rev.nr. 208/2004, date 20.07.2005. In this case, the Municipal and District Courts of Prizren had annulled a contract of donation (signed in 1959) pursuant to Article 103.1 of the FYRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978). According to this provision, “A contract contrary to compulsory regulations, public policy or fair usage shall be void unless the purpose of the rule violated refers to another sanction, or unless the law provides for something else in the specific case.” Again, the Supreme Court stated that the former Yugoslav law of obligations was not applicable at the time when the contract of donation was concluded and, when arguing that the claim was statute-barred, the court did not make reference to any specific legal act but only referred to general provisions of civil law.

Page 13 of 31 # Nature of the case Co Legal references Status m pe te nt co ur t, ca se no . an d da te of ju dg m en t

5 Calculation of timeframe claiming annulment of Su The Law on Obligational Relationships Final judgment. rescindable contracts pr Official Gazette of SFR Yugoslavia, No. 29/1978: em e Article 111 Co A contract shall be rescindable after being concluded by urt a party having a limited business capacity, should its of conclusion be followed by shortcomings in terms of Ko intention of the parties, or should this be determined by so the present Law or a particular precept. vo , – Article 117 Re (1) A right to claim nullity of a rescindable contract v. shall be terminated one year after becoming Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

nr. aware of the ground for making a contract, 20 namely after the termination of coercion. 2/ (2) That right shall in any event be terminated 20 within a three year period from the day of 10 entering into contract. , da Cf. Article 46 and Article 102 of the Law of Obligational te Relationships, O.G. of the R. of Kosovo nr. 16/2012), 03 date 19.06.2012: .0 1. Article 97 20 A contract shall be challengeable if concluded by a party 13 that has limited capacity to contract, if during conclusion there were errors regarding the parties’ intention, or if so stipulated in the present Law or any other act of law.

Article 102 1. The right to request the annulment of a challengeable contract shall expire one year from the day the entitled person learnt of the grounds for challengeability, or one (1) year after the end of duress. 2. In any case this right shall expire three (3) years after the day the contract was concluded.

Page 15 of 31 Article 560. Definition 1. Through a contract of lifelong maintenance a contracting party (the maintaining party) undertakes to support the other contracting party or any other person (the maintained party), and the other contracting party declares that he/she will leave the former all or part of his/her property comprising real estate and the movable property intended for the use and enjoyment of the real estate, whereby the delivery thereof is deferred until the deliverer’s death. 2. Such a contract may also cover other movable property of the maintained party, which must be cited in the contract. 3. Contracts by which against a promise of inheritance a union for life or a community of property is agreed or one contracting party agrees to take care of and protect the other, work his/her estate and attend to a funeral after his/her death or anything else for the same purpose shall also be deemed contracts of lifelong maintenance.

Facts of the case

On 05.02.1996, the Plaintiff, as maintained party, concluded with the Defendant (her husband), as maintaining party, a contract of lifelong maintenance2. The contract was certified by the Municipal Court of Pristina on 05.2.1996. The object of this contract was a cadastral land plot.

On 15.12.2004, the Defendant transferred the disputed land plot to a third party, pursuant to a contract of gift which the Municipal Court of Pristina certified on 20.12.2003. Therefore, the Plaintiff filed a claim in the Municipal Court of Pristina, seeking annulment of the contract of gift on the grounds that the Defendant had disposed of immovable property which would have only be delivered to him after the Plaintiff’s death. The court rejected the Plaintiff’s claim as being statute-barred, since it had been lodged after the lapse of the limitation period foreseen in Article 117.2 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), i.e. three (3) years from the conclusion of the contract. In this regard, the court referred to the circumstances that the contract of gift was concluded on 20.12.2003, whereas the claim for contract annulment was filed on 24.07.2008. Following

2 The lifelong maintenance contract is the one whereby one party undertakes to transfer the other party one or more assets in exchange for the maintenance and care obligation throughout his/her life. This contract was originally regulated by the Law on Inheritance (1965), SFRY OG No. 42/65, and 47/65, Article 122. See also Special Law on Autonomous Province of Kosovo, KSAK OG No. 43/74, Article 105. Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries the Plaintiff’s appeal, the second-instance court upheld the decision of the Municipal Court of Pristina.

Subsequently, the Plaintiff exercised an extraordinary legal remedy by submitting a request for revision to the Supreme Court of Kosovo. This court found that the claim was grounded due to wrong application of the material law by the lower instance courts. The Supreme Court referred to Article 111 and Article 117(2) of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), arguing that none of the lower instance courts sought to prove when the Plaintiff became aware of the existence of the contract of gift entered into between the Defendant and the third party.

On these grounds, the Supreme Court annulled the decisions of the courts of second and first instance and returned the case for retrial to the Basic Court of Pristina, stating that that in order to assess whether the Plaintiff had duly lodged his claim for contract annulment within the timeframe set forth in Article 117, the court of first instance should have determined the moment when the Plaintiff had become aware of the existence of the contract of gift.

Legal issue/s

The judgment concerns the question of calculation of the limitation periods for claiming annulment of voidable contracts pursuant to Article 111 and Article 117 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978).

Abstract of judgment (general rule or principle of law)

In the case where the maintaining party donates (prior to the death of the maintained party) the property left to him/her by the maintained party, in exchange for the obligation of maintenance undertaken pursuant to a lifelong maintenance contract, the limitation period for annulment of the contract of gift referred to under Article 117 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978) shall be interpreted as running from the date when the maintained party became aware of the contract of gift, regardless of when such contract was concluded.

If relevant – comments

This judgment raises serious concerns for two different reasons. First, the Supreme Court misreads Article 117 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978) in such a manner that it writes off paragraph 2 of this article, which foresees an absolute limitation period of three years as the maximum time limit within which action can be brought to annul a contract. According to this provision, a contract is no longer annullable after three

Page 17 of 31 years from the date of conclusion, irrespective of when the party willing to claim annulment has become aware of the grounds for annulment. In an effort to give primacy to the relative limitation period foreseen under paragraph 1, the Supreme Court completely disregards the above-mentioned rule and re-writes Article 117. As a result, the Supreme Court interprets the law contrary the latter’s literal meaning. Theory knows such kind of interpretation as an interpretation contra legem. Second, the Supreme Court could have more properly addressed the issue from the point of view of nullity/voidness of the contract due to contrariety to mandatory legal provisions, given that the maintaining party disposed through donation of immovable property which would only be delivered to him after the death of the maintained party, in violation of the law. In fact, the right of action to declare nullity of a contract is imprescriptible.

# Nature of the case Co Legal references Status mp ete nt cou rt, cas e no. an d dat e of jud gm ent

6 Nullity of settlement of claim concerning the Su The Law of Obligational Relationships, Published in the Final judgment. compensation of moral damages pre Official Gazette of the SFRY nr. 29/1978: me Co Article 103. Nullity urt, (1) A contract contrary to compulsory regulations, Re public policy of fair usage shall be void unless the v.nr purpose of the rule violated refers to another sanction, . or unless the law provides for something else in the 23 specific case. Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

9/2 (2) Should entering into a particular contract be 01 prohibited to one party only, the contract shall remain 2, valid unless otherwise provided by law for the specific dat case, while the party violating the statutory prohibition e shall suffer corresponding consequences. 15. 03. Article 1094. Excessive Damage 20 It shall not be possible to request revocation of the 13 settlement on the ground of excessive damage.

Cf. Articles 89 and 1052 of the Law of Obligational Relationships, O.G. of the R. of Kosovo nr.16/2012, date 19.06.2012.

Article 89. Nullity (1) A contract that contravenes the public order, compulsory regulations or moral principles shall be null and void if the purpose of the contravened rule does not assign any other sanction or if the law does not prescribe otherwise for the case in question. (2) If one party alone is prohibited from concluding a specific contract the contract shall remain in force unless stipulated otherwise by law for the case in question, while the party that infringed the legal prohibition shall bear the appropriate consequences.

Article 1052. Excessive deprivation The annulment of settlement may not be demanded for reason of excessive deprivation.

Page 19 of 31 Facts of the case

The Plaintiff suffered moral damages as a result of a traffic accident which occurred on 13.05.2002 due to the Defendant’s fault. On 18.02.2003, the parties to the dispute settled a claim to compensation for non-monetary damages. According to the terms of the settlement agreement, the Defendant agreed to pay to the Plaintiff the amount of 950 euro as compensation for the non-monetary damages suffered by the Plaintiff in the accident. The Defendant effected the agreed payment and the Plaintiff accepted such payment.

However, after having received the agreed payment the Plaintiff lodged a claim against the Defendant in the Municipal Court of Pristina, requesting the nullity of the settlement agreement on the grounds that such agreement failed to specify the type of damage which the Plaintiff suffered from. Furthermore, the Plaintiff claimed that he was not represented by his lawyer when negotiating the terms of the settlement agreement. The Plaintiff therefore contended that, not being aware of his rights, he was unable to assess whether the amount of compensation offered to him was satisfactory or not. The Plaintiff added that the compensation received from the Defendant did not adequately compensate him for injuries sustained and that he was entitled to greater compensation for the sake of fairness.

The Municipal Court in Pristina rejected the claim of the Plaintiff as being “manifestly ill-founded” with the reasoning that the parties had been free to negotiate and conclude the settlement agreement vis-à-vis the disputed claim, provided that the agreement did not contradict with mandatory rules of law. The first-instance decision was subsequently upheld by the District Court in Pristina.

Afterwards, the Plaintiff filed a revision request in the Supreme Court of Kosovo, arguing that both courts of first and second instance had wrongly assessed the facts and incorrectly applied the material law. The Plaintiff also contended that the judgment had not provided a detailed account of the evidence substantiating the underlying claim. The Court rejected the Plaintiff’s request and confirmed the previous decisions of the lower courts.

Furthermore, the Court stated that the nullity of such a type of contract, i.e. settlement of claims, cannot be invoked on the grounds of the principle of excessive damage (“laesio enormis”) as foreseen in Article 1094 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978). In the opinion of the Court, the purpose of the settlement agreement is to enable private parties to settle peacefully a dispute by making mutual concessions to each other based on free will. Therefore, once parties have reached an agreement and settled their dispute without breaching any mandatory rules of law, the agreement can no longer be revoked under the laesio enormis argument.

Legal issue/s

This judgment concerns the question whether a settlement agreement may be considered null and void pursuant to Article 103 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978) in circumstances other than those where such agreement does not conflict with mandatory rules of law. It also addresses the issue whether an agreement related to the settlement of claims may be revoked (annulled) on the grounds of excessive damage (“laesio enormis”) based on Article 1094 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978). Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

Abstract of judgment (general rule or principle of law)

According to Article 103 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), a settlement agreement shall not be considered null and void under circumstances other than those in which the agreement is contrary to mandatory rules of law, such as in circumstances where the settlement does not specify the type of damage for the compensation of which it has been reached, or where a party was not represented by a lawyer when it negotiated the terms of the settlement. Furthermore, the revocation (nullity) of a settlement shall not be invoked on the grounds of excessive damage (“laesio enormis”), pursuant to Article 1094 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), when the settlement agreement was concluded based on the free will of the parties.

If relevant – comments

This judgment is still relevant in light of the fact that the content of the provisions of Articles 89 and 1052 of the new Law on Obligational Relationships (2012) is very similar to that of Articles 103 and 1094 of the old SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978). See in the same sense Supreme Court of Kosovo – Rev. nr. 47/2005, date 29.12.2005.

# Nature of the case Co Legal references Status m pe te nt co ur t, ca se no . an

Page 21 of 31 d da te of ju dg m en t

7 Reimbursement of “unlawful” penalty interest Co The Law of Obligational Relationships, Official The Court of Appeals collected by a financial institution. Unjustified urt Gazette of the SFRY nr. 29/1978: CONFIRMS the enrichment. of judgment of the Ap Article 210 Economic Court II.C.nr. pe (1) After part of a person’s property is transferred in 272/11, date 30.01.2012. als any kind of way to another, and such transfer has no The judgment is final. , ground in any legal transaction or in the law, the one Ae who acquires property in such a way shall be bound to .nr restitute it, and should this be impossible – to pay . damages in the value of benefits gained. 35 (2) The duty of restitution, or paying damages shall 2/ also arise if something is received on a ground which 20 did not materialize, or which subsequently ceased to 12 exist. , da Article 270. General Rules te (3) Liquidated damages shall not be stipulated in 07 relation to monetary obligations; .0 6. Article 277. When Owed 20 (1) A debtor being late in the performance of a 13 pecuniary obligation shall owe, in addition to the principal, default interest, at the rate determined by federal council. (2) Should the rate of stipulated interest be higher than the rate of default interest, it shall continue to run even Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

after the debtor’s delay.

Cf. Articles 194, 381-383 of The Law of Obligational Relationships, O.G. of the R. of Kosovo nr. 16/2012), date 19.06.2012:

Article 194. General rule (1) Any person that without a legal basis becomes enriched to the detriment of another shall be obliged to return that which was received or to otherwise compensate the value of the benefit achieved. (2) The term enrichment also covers the acquisition of benefit through services. (3) The obligation to return or compensate shall also arise if a person receives something in respect of a basis that is not realized or subsequently disappears.

Article 381. Presumption of usurious interest (1) If the agreed interest rate for penalty or contractual interest is more then fifty percent (50%) higher than the prescribed penalty interest rate, calculated as per the following Article, such an agreement shall be deemed a usurious contract, unless the creditor shows that the creditor has not exploited the debtor’s distress, the severity of the pecuniary situation thereof, or the inexperience, recklessness or dependence thereof, or that the benefits reserved for the former or for a third person are not in clear disproportion to that which the former provided or did

Page 23 of 31 or undertook to provide or do.

Article 382. Penalty interest (1) A debtor that is in delay in performing a pecuniary obligation shall owe penalty interest in addition to the principal. (2) The interest rate for penalty interest shall amount to eight percent (8%) per annum, unless stipulated otherwise by a separate act of law.

Article 383.Contractually agreed penalty interest rate

The creditor and the debtor may agree that the penalty interest rate be lower or higher than the penalty interest rate prescribed by law.

Facts of the case

In 2005 and 2006, the Plaintiff (a business organisation) concluded with the Defendant (a bank) two different loan contracts for the total amount of 260,000 euro, with an annual contractual interest rate of 13.5% and a default interest of 3% per month or fraction thereof on any unpaid amounts.

In 2007, the Plaintiff failed several times to repay the loan as per the payment plan. Due to the Plaintiff’s default, the collateral securing the loan was seized and resold by the Defendant (through a public auction) and the proceeds of collateral were applied toward the satisfaction of the secured debt, the contractual interest and the penalty interest accrued.

The Plaintiff lodged a claim in the Economic Court in Pristina arguing that the Defendant should be ordered to pay back to him the amount of 44,640.54 euro as such amount had been paid to the Defendant as “unlawful” penalty interest. The Plaintiff disputed the legal basis for the penalty interest collected by the Defendant. The Economic Court in Pristina found that the Plaintiff’s claim was grounded as it considered that the clauses of the loan contract setting the monthly penalty interest at 3% (or yearly at 36%) were unlawful, and therefore declared the contractual clauses null and void. As a result, the Defendant, on the grounds of the principle of unjustified enrichment, was ordered to pay back to the Plaintiff the penalty interest collected.

Afterwards, the Defendant filed an appeal in the Court of Appeals on the grounds that the Economic Court of Pristina had wrongly applied the material law by applying in the given circumstances paragraph 3 of Article 270 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978). However, the Court rejected the Defendant’s request as manifestly ill-founded and upheld the judgment of the Economic Court of Pristina. Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

Legal issue/s

This case deals with the question whether the penalty interest foreseen in the context of a loan contract is “lawful” under paragraph 3 of Article 270 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), and if not, whether the penalty interest collected by the Defendant should be returned to the Plaintiff based on the principle of “unjustified enrichment” as enshrined in paragraphs 1 and 2 of Article 210 of the same law.

Abstract of judgment (general rule or principle of law)

Based on Article 270(3) of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), the clauses of a loan agreement related to penalty interest are to be regarded as unlawful, and the penalty interest, if collected by the Defendant, shall be paid back to the Plaintiff, in accordance with the principle of unjustified enrichment enshrined in Article 210(1) and (2) of the same law.

If relevant – comments

It is arguable that the Court has wrongly interpreted and applied the material law, notably paragraph 3 of Article 270 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978), when concluding that “the penalty interest clauses incorporated in the loan agreement” are null and void.

The provision of Article 270(3) relates to liquidated damages and stipulates that this form of compensation is not applicable to monetary obligations. By qualifying the monthly default interest rate of 3% as “liquidated damage” and inferring from this that the related clause was unlawful, the Court totally overlooked Article 277(1) of the same law, which establishes that “a debtor being late in the performance of a pecuniary obligation shall owe, in addition to the principal, default interest, at the rate determined by the federal council”.

Of course, this provision makes reference to an authority which does not exist in Kosovo since 1999. However, while the reference to “the federal council” may only be relevant for the purposes of determining the exact amount of the applicable interest rate, it is undisputable that Article 277(1) sanctions the creditor’s right to “default interest” in case the debtor is late in the performance of a pecuniary obligation.

It appears, therefore, that the Court may have fallen into error and confused (perhaps, intentionally) the principle of “default interest”, which is always due in case of late performance of monetary obligations, with the concept of “liquidated damage”, which is a form of pre-determined compensation applicable to non-monetary obligations only, such as the provision of a service.

Page 25 of 31 The question of lawfulness of penalty interest in the context of a loan agreement should have been more correctly addressed in light of Article 277 of the SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978). From this perspective, the Court should have asked itself whether the default interest rate foreseen in the loan agreement was in accordance with the consumer credit laws, including those applicable in matters of usury. However, as a new law of obligations entered into force in December 2012, the relevance of this judgment is limited by the fact that it does not apply to cases instituted thereafter, unless the case refers to facts which occurred prior to the entry into force of the new legislation.

The existing Law on Obligations Relationships (2012) provides in Article 382(1) that if the debtor fails to pay a pecuniary obligation, the same owes to the creditor the penalty interest in addition to the principal. The following Article 383 guarantees the parties’ autonomy to negotiate and agree the penalty interest rate. If parties fail to establish a penalty interest rate in their contract, paragraph 2 of Article 382 clarifies that the penalty interest rate amounts to 8% per annum, unless otherwise stipulated by law. According to Article 381 of the same law, in the context of contractual relations other than commercial contracts, the penalty interest shall not be above the yearly scale of 12% of the principal, i.e. 50% higher than the prescribed penalty interest rate.

# Nature of the case C Legal references Status o m pe te nt co ur t, ca se no . an d da te of ju dg m Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

en t

8 Construction contract / Additional remuneration for Su The Law of Obligational Relationships, Official Gazette Final judgment. unforeseen work executed without prior written pr of the SFRY nr. 29/1978: approval. e m Article 630. Notion e (1) A contract of construction shall be a contract for C services by which a contractor assumes the obligation to ou construct, rt according to a specific plan and within a stipulated time of limit, a specific building on an agreed building site, or to K perform on such building site, or on an already existing os facility, some other civil engineering works, while the ov purchaser assumes the obligation to pay in return an o, agreed pice. E. (2) A contract of construction must be concluded in R written form. ev .n Article 633. Departure from a Construction Plan r. (1) Every departure from a construction plan, or works 22 stipulated, effected by the supplier shall need written /2 approval 01 from the purchaser. 3, (2) He shall not be entitled to demand increase of price da stipulated for works done by him without such approval. te 13 Article 634. Urgent and Unforeseen Works .1 (1) Unforeseen works may be done by a contractor even

Page 27 of 31 1. without previous approval by the purchaser if, due to 20 their urgency, he was not able to obtain such approval. 13 (2) Unforeseen works shall be works the undertaking of which is necessary in order to ensure stability of a facility, or to prevent damage, and which were caused by an unexpectedly less favourable quality of soil, unexpected occurence of water or other extraordinary and unexpected events. (3) The contractor shall be bound to notify the purchaser without delay about such phenomena and of measures taken. (4) The contractor shall be entitled to fair remuneration for the unforeseen works which had to be done. (5) The purchaser may repudiate the contract if, due to such works, the price stipulated would have to be considerably raised, while being obliged to notify the contractor accordingly and without delay. (6) In case of repudiation of contract, the purchaser shall be bound to pay to the contractor a corresponding part of the price for works already carried out, as well as fair remuneration covering his necessary expenses.

Cf. Articles 645, 648, 649 of the Law of Obligational Relationships, O.G. of the R. of Kosovo nr. 16/2012, date 19.06.2012:

Article 645. Definition (1) A building contract is a contract for work through which the contractor undertakes to build a specific structure on specific land according to a specific plan by a specific deadline or to carry out any other construction work on such land or on an existing structure, and the ordering party undertakes to pay the contractor a specific fee for the work. (2) A building contract must be concluded in written Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

form. Article 648. Deviation from plan (1) The contractor must have written approval from the ordering party for any deviation from the construction plan or the contracted works. (2) The contractor may not demand an increase to the agreed fee for works performed without such approval.

Article 649. Urgent unforeseen works (1) The contractor may also carry out urgent unforeseen works without the ordering party’s prior approval if this cannot be supplied because of the urgency of the works. (2) Unforeseen works are those that had to be performed urgently to ensure the stability of the structure or to prevent the occurrence of damage, and that were caused by the unexpectedly heavy nature of the land, unexpected water or any other extraordinary, unexpected development. (3) The contractor must notify the ordering party without delay regarding such phenomena and the measures taken. (4) The contractor shall have the right to fair payment for the unforeseen works it was necessary to perform. (5) The ordering party may withdraw from the contract if the agreed fee would be considerably higher owing to such works; the ordering party must notify the contractor of such without delay. (6) In the event of withdrawal from the contract the ordering party must pay the contractor an appropriate

Page 29 of 31 part of the fee for the work already performed, and a fair reimbursement of the necessary costs.

Facts of the case

The Plaintiff (a private company) and the Defendant (a state agency) concluded two construction contracts (no. 01/04 no. 02/04) on 25.04.2004, pursuant to Article 630 of the SFRY on Obligational Relationships (1978). According to these contracts, the Defendant – as contracting authority – contracted the Plaintiff – as contractor – in order to execute work related to the construction and expansion of the pipelines for telephone cables in Peja and Decan, respectively for the price of 392,270.40 euro and 118,817.24 euro.

Apart from what agreed in the construction contracts, the Plaintiff executed some additional work unrelated to the contract in the neighborhood “Dubrave” of the city of Istog, the cost of which reached the amount of 87,504.98 euro. Although this additional work was not foreseen in the contracts entered into between the parties, its execution was apparently requested by an official of the contracting authority.

The Plaintiff, which despite its request was denied further compensation for the additional work executed, lodged a lawsuit against the Defendant in the Economic District Court in Pristina. In its ruling, this court rejected the Plaintiff’s claim as manifestly ill-founded, arguing that the Plaintiff should have sought approval from the Defendant in advance of commencing the execution of the disputed work.

Thereafter, the Plaintiff filed a request for revision of the above-mentioned judgment in the Supreme Court of Kosovo, on the grounds that the Economic District Court in Pristina had wrongly assessed the facts of the case and wrongly applied the material law.

On 13.11.2013, the Supreme Court confirmed the judgment of the Economic District Court, arguing that – as set forth in Article 633 of the SFRY on Obligational Relationships (1978) – every departure from the construction plan agreed between the contractor and the contracting authority needs the written agreement of both parties, the only exception to the rule being the case where the departure from the said plan is required by reason of the urgency of the situation, which prevents the contractor from obtaining such approval in due time, in accordance with Article 634 of the SFRY on Obligational Relationships (1978). The Court further stated that in the present case the Plaintiff failed to prove the urgent nature of the work departing from the original construction plan; therefore, the Plaintiff was not entitled to claim any additional remuneration for the unforeseen work executed.

Legal issue/s

This judgment concerns the question whether the contractor may be entitled to additional remuneration for the execution of work unforeseen in the construction contract if the contractor did not obtain previous written approval from the contracting authority nor was it able to convince the court that urgent circumstances prevented it from obtaining such approval.

Abstract of judgment (general rule or principle of law) Support to Civil Code and Property Rights EuropeAid/133833/C/SER/XK Contract No. 2014/344-574

Ref: Annex 05 to the 1st Progress Report (January 2015)

Subject: Law of Obligations Case Law Summaries

Pursuant to Article 630, read in conjunction with Articles 633 and 634, of the SFRY on Obligational Relationships (1978), the contractor shall not be entitled to an increase of remuneration for the execution of work unforeseen in the construction contract in the case where the contractor failed to seek written approval from the contracting authority prior to the execution of such work, and the contractor was unable to give evidence in court of the urgent circumstances that prevented it from obtaining such approval.

If relevant – comments

Although this judgment relates to the old Yugoslav law of obligations, it is still relevant in light of the fact that the provisions of Articles 645, 648 and 649 of the new Law on Obligational Relationships (2012) are very much alike the provisions of Articles 630, 633 and 634 of the old SFRY Law on Obligational Relationships (1978).

The judgment confirms the principle that the written form requirement is an essential element of the construction contract; hence, any change of such contract shall be effective only if executed in writing by both parties to the contract. Because of this, every departure from the original plan effected by the contractor shall need the previous written approval of the contracting authority.

The only exception to this rule is the case where the two following conditions are met: (a) the contractor is required to deviate from the construction plan in order to face unexpected circumstances of an extraordinary nature, such as structural instability or an imminent threat of damage, and (b) due to the urgency of such circumstances, the contractor is unable to obtain prior written approval from the contracting authority in regards to the unforeseen work to be executed.

In the present case, the contractor (Plaintiff) failed to convince the Court about the urgency of the additional work executed and, therefore, the Court concluded that it was not entitled to receive additional remuneration from the contracting authority (Defendant).

Page 31 of 31