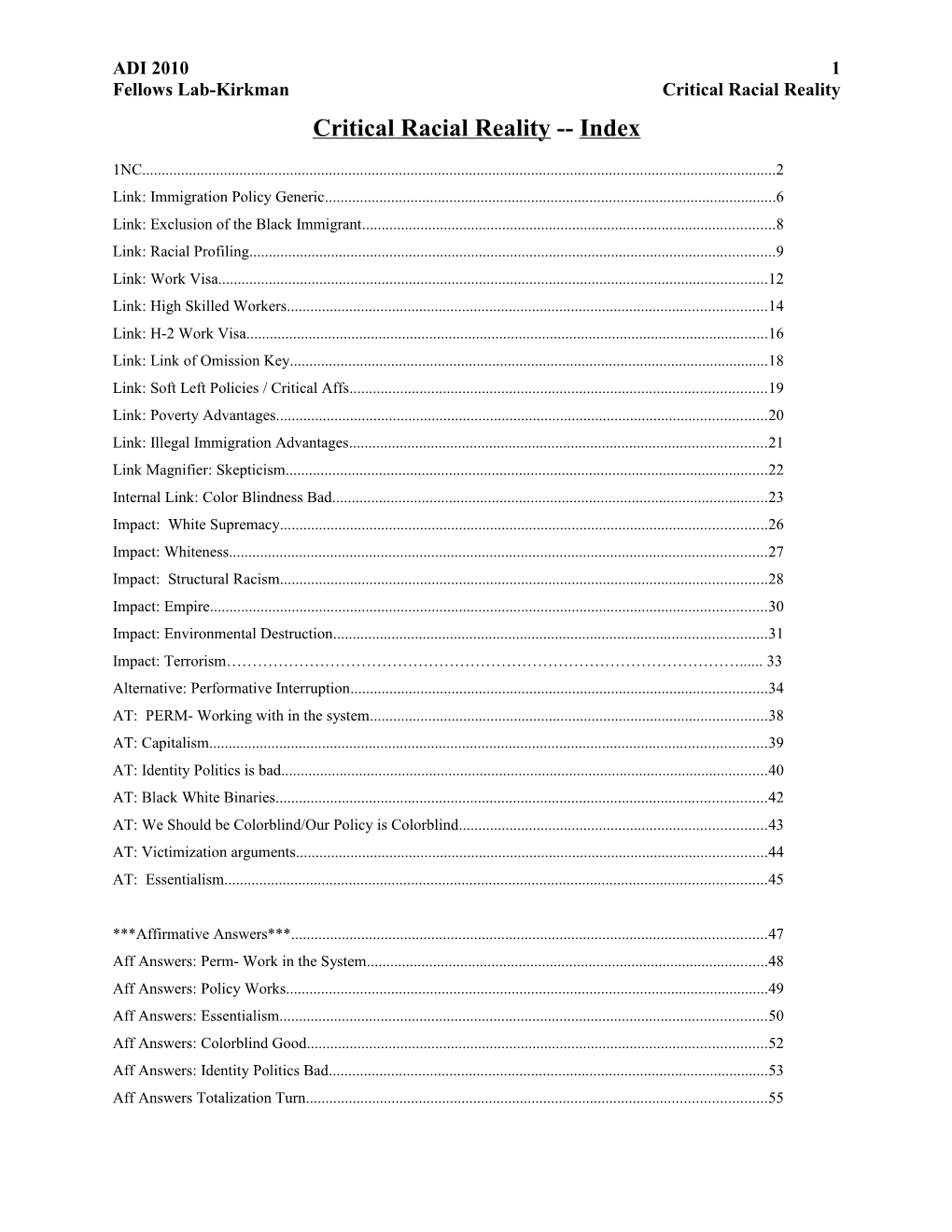

ADI 2010 1 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Critical Racial Reality -- Index

1NC...... 2 Link: Immigration Policy Generic...... 6 Link: Exclusion of the Black Immigrant...... 8 Link: Racial Profiling...... 9 Link: Work Visa...... 12 Link: High Skilled Workers...... 14 Link: H-2 Work Visa...... 16 Link: Link of Omission Key...... 18 Link: Soft Left Policies / Critical Affs...... 19 Link: Poverty Advantages...... 20 Link: Illegal Immigration Advantages...... 21 Link Magnifier: Skepticism...... 22 Internal Link: Color Blindness Bad...... 23 Impact: White Supremacy...... 26 Impact: Whiteness...... 27 Impact: Structural Racism...... 28 Impact: Empire...... 30 Impact: Environmental Destruction...... 31 Impact: Terrorism………………………………………………………………………………………...... 33 Alternative: Performative Interruption...... 34 AT: PERM- Working with in the system...... 38 AT: Capitalism...... 39 AT: Identity Politics is bad...... 40 AT: Black White Binaries...... 42 AT: We Should be Colorblind/Our Policy is Colorblind...... 43 AT: Victimization arguments...... 44 AT: Essentialism...... 45

***Affirmative Answers***...... 47 Aff Answers: Perm- Work in the System...... 48 Aff Answers: Policy Works...... 49 Aff Answers: Essentialism...... 50 Aff Answers: Colorblind Good...... 52 Aff Answers: Identity Politics Bad...... 53 Aff Answers Totalization Turn...... 55 ADI 2010 2 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality 1NC

A. Whiteness has assumed the position of an uninterrogated space leaving us unable to know what “whiteness” means. Yet we perceive whiteness as if it has a normative essence. By viewing whiteness as a rhetorical construction we expose its invisibility which has been manifested through its universality.

Nakayama & Krizak, 1995 Asst Prof, Dept of Communication @ Arizona State Univ. & Asst Prof, Dept of Communication @ St. Louis Univ. Thomas K. & Robert L.“WHITENESS: A Strategic Rhetoric”; Quarterly Journal of Speech, 81, 291-309

Historically, the development of the study of communication has followed a focus on the center. Plato and Aristotle, from a privileged class, were not interested in theorizing or empowering ways that women, slaves, or others culturally marginalized people might speak. The rhetor was always already assumed to be a member of the center. Spelman argues that “both Plato and Aristotle have a normative notion of humanness that is inseparable from a notion of masculinity (which is of course normative)” (54). Spelman’s analysis demonstrates the ways that “race” and gender get conflated in order to center male citizens. While the configuration of the racial/ethnic territory has shifted from the place of ancient Greece to contemporary North America, the assumption of centeredness has remained intact and unquestioned. As a consequence of this historical framework, in U.S. culture, whiteness has assumed the position of an uninterrogated space. In sum, we do not know what “whiteness” means. An earlier attempt to get at this problem, by a citizen of the center, underscores an important paradox and risk: When we examine ourselves as whites and all that we stand for in the world today, we find a paradox. We are not what we suppose ourselves to be. We have fancied ourselves the good guys who make a few mistakes. But that is not what we find. (Dutcher 97) The risk for critical researchers who choose to interrogate whiteness, including those in ethnography and cultural studies, is the risk of essentialism. Whatever “whiteness really means is constituted only through the rhetoric of whiteness. There is no “true essence” to “whiteness”; there are only historically contingent constructions of that social location. Foucault’s principle of “exteriority” explains the rhetorical sensibility, rather than essential nature, of discursive events: We are not to burrow into the hidden core of discourse, to the heart of thought or meaning manifested in it; instead, taking the discourse itself, its appearance and its regularity, that we should look for its external conditions of existence, for that which gives rise to the chance series of these events and fixes its limits. (“Discourse on Language” 229) Yet, the social location of “whiteness is perceived as if it had a normative essence. It is important that we acknowledge that “the radicality or conservatism of essentialism depends, to a significant degree, on who is utilizing it, how it is deployed, and where its effects are concentrated” (Fuss 20). By viewing whiteness as a rhetorical construction, we avoid searching for any essential nature to whiteness. Instead, we seek an understanding of the ways that this rhetorical construction makes itself visible and invisible, eluding analysis yet exerting influence over everyday life. The invisibility of whiteness has been manifested through its universality. The universality of whiteness resides in its already defined position as everything. Richard Dyer makes an important point:In the realm of categories, black is always marked as a colour (as the term “coloured”egregiously acknowledges), and is always particularizing: whereas white is not anythingreally, not an identity, not a particularizing quality, because it is everything-white is nocolour because it is all colours. (45)

Thus, the experiences and communication patterns of whites are taken as the norm from which Others are marked. If we take a critical perspective to whiteness, however, we can begin the process of particularizing white experience. This move displaces whites from a universal stance which has tended to normalize and to naturalize their positionality to a more specific social location in which they confront the kinds of questions and challenges facing any particular social location. As Frye underscores, “What this can mean to white people is that we are not white by nature but by political classification” (118). In light of the influential political position of whiteness, it is surprising that critical scholars have not yet scrutinized the center in the ways that they have been probing the margins. Despite the historical domination of the center and the myriad of ways it exerts its influence on the margins, our discipline has not been critical of this dominance over communication studies. In this paper we push the territory of the center in new directions, much as critical scholars have pushed the margins. By critically examining this space, it gains particularity, while losing universality. We see this conceptual move as one that is counterhegemonic, as it challenges the normalizing position of the center, whiteness. ADI 2010 3 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality B. This purported neutrality is also seen in immigration laws but also the enforcement of those laws

Hing 2009, Professor of Law at UC Davis Bill Ong “Institutional Racism ICE Raids and Immigration Reform “ University of San Francisco Law Review Fall 2009

Based on the manner in which immigration laws and enforcement policies have evolved, racism has been institutionalized in those laws and policies. However, writers such as john powell n136 urge us to do more and to examine how different institutions interrelate with one another to produce an even more sinister dynamic. n137 Thus, powell encourages us to look beyond the institutionalized racism within U.S. immigration laws and enforcement policies that has become part of the "structure" of those laws and policies, and to look at the interaction between institutions for what he terms "structural racism." n138 Whatever the terminology, powell invites us to take the institution of immigration laws and policies and see how that institution relates to other institutions that can produce racial outcomes. It does not take long to realize that while immigration laws and enforcement policies have evolved in a manner that continues to prey on Mexicans, Asians, and other Latin migrants, the relationship of those laws and policies with other racialized institutions underscores the structural challenges that immigrants of color face. Consider the NAFTA and the World Trade Organization. NAFTA has placed Mexico at such a competitive disadvantage with the United States in the production of corn that Mexico now imports most of its corn from the [*347] United States, and Mexican corn farm workers have lost their jobs. n139 The U.S.- embraced World Trade Organization, which advocates global free trade, favors lowest-bid manufacturing nations like China and India, so that manufacturers in a country like Mexico cannot compete and must lay off workers. n140 Is there little wonder that so many Mexican workers look to the United States for jobs? Think also of refugee resettlement programs as an institution. When Southeast Asian refugees are resettled in public housing or poor neighborhoods, their children find themselves in an environment that can lead to bad behavior or crime. n141 Consider U.S. involvement in wars and civil conflict abroad. Think also of U.S. involvement in places like Vietnam, Afghanistan, or Iraq - places that have produced involuntary migrants of color to our shores. Other racialized institutions that interact with immigration laws and enforcement also come to mind: the criminal justice system, poor neighborhoods, and inner city schools. Even coming back full circle to enslavement of people - today's human trafficking institutions - we begin to realize a sad interaction with immigration laws that requires greater attention. All of these institutions can lead to situations that spell trouble within the immigration enforcement framework. The immigration admission and enforcement regimes may appear neutral on their face, but (1) they have evolved in a racialized manner and (2) when the immigration framework interacts with other racialized institutions you realize that the structure generates racial group disparities as well. NAFTA and globalization form a big part of why many migrants of color cannot remain in their native countries. The criminal justice system and poverty prey heavily on poor communities of color, leading to deportable offenses if defendants are not U.S. citizens. ADI 2010 4 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality C. The Impact: This invisibility allows for white supremacy to be the underpinning of ALL system of domination

Mill 97, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Illinois Charles writes in his book the Racial Contract in 1997, p.1

White supremacy is the unnamed political system that has made the modern world what it is today. You will not find this term in introductory, or even advanced, texts in political theory. A standard undergraduate philosophy will start off with Plato and Aristotle, perhaps say something about Augustine, Aquinas, and Machiavelli, move on to Hobbes, Locke, Mill, and Marx, and then wind up with Rawls and Nozick. It will introduce you to notions of aristocracy, democracy, absolutism, liberalism, representative democracy, socialism, welfare capitalism, and libertarianism. But though it covers more than two thousand years of western political thought and runs the ostensible gamut of political systems, there will be no mention of the basic political system that has shaped the world for the past several hundred years. And this omission is not accidental. Rather, it reflects the fact that standard textbooks and courses have for the most part been written and designed by whites, who take their racial privilege so much for granted that they do not even see it as political, as a form of domination. Ironically, the most important political system of recent global history—the system of domination by which white people have historically ruled over and, in certain important ways, continue to rule over nonwhite people-is not seen as a political system at all. It is jus taken for granted, it is the background against which other systems, which we are to see as political, are highlighted. ADI 2010 5 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality D. Next the Alternative First the Text: We as debaters and people should engage in a constant interruption of whiteness as the dominant cultural norm. AND This is the most effective means of subverting the political system of white supremacy by approaching the transcendence of self and other

Warren and Fassett, 4, assistant professor in the School of Communication Studies at Bowling Green State University, where he teaches courses in performance, culture, identity, and assistant professor in the Department of Communication Studies at San José State University, where she teaches courses in instructional communication and critical, feminist, and performative pedagogies. John T. and Deanna L., Theatre Topics 14.2 (2004) 411-430 (pp. 414-415) Performative pedagogy, while still an undertheorized site of investigation (and pedagogical practice), has groundings in various fields ranging from dance and theatre to English and communication studies. Our commitment to performative pedagogy emerges from traditions of oral interpretation—a field of study where researchers and teachers feel one can develop a thoughtful and complex understanding of a literary or popular text, such as a poem, by performing that text, by reading that text through the body. Wallace A. Bacon's work on the potential of performance is indeed persuasive: "The performing act comes as close, perhaps, as we shall ever get to the transcendence of self into other. It is a form of knowing—not just a skill for knowing, but a knowing. [. . .] If the engagement is real, not simply pretended, the self grows" (73). While Bacon here discusses the transcendence of self into the other, his work is a possible way of thinking through whiteness—where whiteness is so invisible to the perceiving white subject that his own racial identity is effectively othered. Thus, the engagement with whiteness is an engagement with the other, a reconceptualization of the self as other. Certainly the work of Boal is key in this process of engagement. His work on forum theatre alone can be imagined as a productive and engaging site of understanding how power is situated in our lives, in our bodies. His work has been framed by several scholars as performative—most clearly by Elyse Lamm [End Page 414] Pineau, who, aligning her work with Boal's, argues that performative pedagogy is a trickster (that is, subversive) pedagogy. Pineau offers four ways of framing and defining performative pedagogy, noting that through this pedagogical method one might assist in challenging and subverting systems of power such as whiteness. She frames this redefinition as educational poetics, play, process, and power (15). In "Educational Poetics," the banking mode of education characterized by traditional information dispensing into waiting students is reframed into an "educational enterprise [that is] a mutable and ongoing ensemble of narratives and performances" (10). "Educational Play" resituates pedagogy in the body, asking students and teachers to engage in corporeal play—a mode of "experimentation, innovation, critique, and subversion" (15). "Educational Process," on the other hand, acknowledges that identities are always multiple, overlapping, ensembles of real and possible selves who enact themselves in direct relation to the context and communities in which they perform. ADI 2010 6 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link: Immigration Policy Generic

Immigration enforcement has a institutional bias against people of color

Hing 9, Professor of Law @ UC Davis Bill Ong “Institutional Racism ICE Raids and Immigration Reform “ University of San Francisco Law Review Fall 2009

During their interviews with ICE agents at the plant, the alleged undocumented workers were asked if they had children, but were not told that one of the parents would be allowed to remain to care for them. ... Immigration Policy This Article contends that the evolution of immigration laws and the manner in which immigration laws operate have institutionalized bias against Latino immigrants - Mexicans in particular - and Asian immigrants. ... By the mid 1990s, eighty-eight percent of the Border Patrol's agents were stationed along the Mexican border, and southern border apprehensions accounted for ninety-eight percent of all border apprehensions. . ... The categories of deportable aliens include the following: those who are in the United States in violation of the immigration laws (e.g., entry without inspection, false claim to citizenship); those non-immigrants who overstay their visas or work without authorization; those who have helped others enter (smuggled) without inspection; and those who are parties to sham marriages. ... From Dehumanization and Demonization to Criminalization The institutionalized racism of U.S. immigration laws and enforcement policies reflects the evolution of immigration laws that grappled with constant tension over who is and who is not acceptable as a true American. ... Given what we now know about the evolution of the immigration selection system, initial attention should be paid to the number of visas that are available to Latin and Asian countries. ... They have been set up by the vestiges of blatantly racist Asian exclusion laws, a border history of labor recruitment like the Bracero Program, Supreme Court deference to enforcement, and border militarization that laid the groundwork for current laws and enforcement policies. ... Many in the immigrant rights movement argue that the appalling effects of ICE raids, deaths at the border that result from its militarization, horrible backlogs in family immigration categories, immigration detention conditions, and the lack of second chance opportunities for longtime, lawful permanent residents convicted of aggravated felonies are sufficient bases for overhauling immigration laws and enforcement policies. ... As long as we remain mired in the belief that we need to prevent undocumented workers from working in the country through an employer sanctions system, workers will continue to get deported, families will be separated, and communities will suffer damage. ADI 2010 7 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Immigration raids and how they are conducted are filled with racial overtones that hurt people of color

Hing 9, Professor of Law @ UC Davis Bill Ong, “Institutional Racism ICE Raids and Immigration Reform “ University of San Francisco Law Review Fall 2009

ON A COLD, RAW DECEMBER MORNING in Marshalltown, Iowa, Teresa Blanco woke up to go to work at the local Swift meat packing plant. Hundreds of others across the town were doing the same thing, in spite of the miserable mixture of sleet, mist, and slush that awaited them outside their front doors. As they made their way to the plant, the workers, who were from Mexico, did not mind the weather. n1 Unfortunately, the workers' day turned into a nightmare soon after they reported for work. Not long after the plant opened, heavily armed agents from the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency ("ICE") stormed onto the scene. Pandemonium broke out. The workers panicked; many began to run; others tried to hide, some in dangerous and hazardous areas. n2 As the ICE agents began rounding up all the workers, they ordered those who were U.S. citizens to go to the cafeteria. Noncitizens were directed to a different section of the plant. Agents shouted out instructions: documenteds in one line, undocumenteds in another. If an agent suspected that the person in the citizens' line was undocumented, the agent would instruct the person to get into the undocumented line. More than one individual was told, "You have Mexican teeth. You need to go to that line [for undocumented persons] and get checked." n3 [*308] The nightmare was only beginning. Although supervisory ICE agents carried a civil warrant for a few individuals, the squad demanded that all plant employees be held, separated by nationality. That included U.S. citizen workers who were interrogated and detained. No one was free to leave - not even those who carried evidence of lawful status or proof they were in the process of seeking proper permission to be in this country. Each was interrogated individually. The process took the entire day, and phone calls were not permitted until later in the day. By the end of the day, ninety were arrested, but hundreds, including citizens, had been detained for hours. The entire community was shaken to its core. Although immigration raids are not a recent phenomenon, this Article focuses on a few egregious ICE raids that occurred after President Bush's push for immigration reform in 2004. n4 I had the opportunity to learn more about several such raids first hand as part of a commission that was established by the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union in 2008. n5 The Commission spent more than a year holding regional hearings, interviewing witnesses, and soliciting input from a wide range of workers, elected officials, policy experts, psychologists, and religious and community leaders. Commissioners learned about the abuse that ICE officials visited upon workers, their families, and the communities. This Article's discussion of ICE raids addresses racial profiling, the trauma to children and families, the damage to communities, and some legal considerations. Descriptions of ICE raids challenge us to think more seriously about the underlying racial implications of those raids. The tragic effects on families and communities, as well as the serious constitutional violations committed by ICE agents during the raids, provide ample moral and legal justification to end the raids. The inherent racism at the center of the ICE raids and other ICE and Border Patrol operations raises further concern that receives little public attention. With few exceptions, the ICE operations targeted Latinos - usually Mexicans. The exceptions were Chinese restaurants and other businesses that relied on workers of color. That racial effect is the focus of this Article and the basis for advocating that both immigration policies and ICE enforcement need to be rethought. ADI 2010 8 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link: Exclusion of the Black Immigrant

When Black people immigrate to the United States they are still considered the other

Lewis 9, Law Professor @ Northeastern University Hope Lewis, in “International Law Defining Race Transnational Dimensions of Race in America,” Albany Law Review 2009

Even before entry into the United States, Afro-Caribbean immigrants likely have engaged with the consciousness of race and color in many forms. Their celebrations of independence from British, French, or Spanish rule recognize the racialized character of colonial systems. Yet class and race tensions are also reflected in the phenomenon of "double-consciousness." Some aspire to neo-colonial standards and priorities perceived to be superior to those associated with African and indigenous Caribbean approaches to education, culture, religion, political organization, or resistance. n55 If the Afro- Caribbean immigrants in question have worked in island tourism industries (often a third or more of the economy), they have encountered white and Asian middle-class or wealthy tourists from the U.S., Canada, the U.K., China, and Japan. Increasingly, poor Black women and girls experience the intersection of gender and race stereotypes with the rise of sex tourism. n56 Many Black immigrants have had their fill of racist or racialized images from U.S. and British television and films; others download racial and cultural perceptions from the internet. Caribbean newspapers, radio, and television are filled with reports on the goings-on in the Big Brother countries of the North, including their racial aspirations and conflicts. n57 Some Afro-Caribbean immigrants to the U.S. might have seen their brothers, fathers, uncles, or sons incarcerated in U.S. prisons, then deported back to the islands. Dubbed "deportee violence," crime waves in Caribbean urban centers were blamed on such returnees. n58 [*1012] Ironically, U.S. prosecutors targeted "Jamaican drug posses" as particularly violent expressions of anti-social behavior among young urban Blacks. By contrast, media and politicians on the islands blamed the "taint" of violent American culture and prison life for having hardened the young Black men who returned to the islands after U.S. deportation. n59 When working-class Afro-Caribbean immigrants navigate the treacherous U.S. immigration and security terrain, they see and understand the racial differences in treatment at the airport in addition to the citizen/non-citizen divide. And when they enter the nursing homes, hospitals, day-care centers, and private homes of New York, Boston, or Miami, they see the racial, gender, and class demarcations that trace their lives. Black immigrant women see the irony of spending years caring for other people's children when their own children are being raised at home by grandparents or other relatives. n60 But Black immigrants are still placed by many American observers in an essentialized category of "foreign-born Blacks" and, therefore, exotic others. At one and the same time (and although they have far fewer economic resources than a Powell or Obama now have) they could be labeled "exceptional Blacks" - merely because of their foreign-ness, accent, or cultural differences. On the other hand, immigration or security officials might view them primarily as potential targets for racial/ethnic profiling - as undocumented workers (or visa overstays) or potential drug couriers. Others may treat them as members of the invisible underground who perform the "unskilled" labor that keeps the [*1013] country fed, clean, and cared for. n61 How Black immigrants see themselves in racial perspective is equally complicated. Some do, indeed, buy in to the exceptionalism of foreign-ness beliefs, others internalize the marginalization associated with "illegal" status, and still others identify with native-born Blacks in a complex mix of strategic, political, or cultural solidarity. ADI 2010 9 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality

Link: Racial Profiling

People of color are still discriminated against once they get into the country.

Romero 3, professor of law at Penn State University's Dickinson School of Law Victor C. Romero “Critical Race Theory in Three Acts Racial Profiling Affirmative Action and the Diversity Visa Lottery,”Albany Law Review, Accessed 7/28/09 Lexis

Whether one favors the pejorative Driving While Black (or Brown) or Flying While Arab (or Muslim), the stock liberal argument against racial and ethnic profiling in the law enforcement context is that stereotypical assumptions--that people of color are more apt to commit crime--violate the liberal tenet that each person should be treated as an individual, not as a member of a group. n7 Every innocent individual of color that is stopped on the highway or frisked at the airport is stigmatized by society's suspicion attending a police search. n8 Professor David Harris shares the story of Larry Sykes, the head of the Board of Education in Toledo, Ohio, bank vice-president, and respected civic leader, who was pulled over for no articulated reason on his drive home from an economic development conference in Cleveland. n9 Despite his having been dressed in a crisp business suit and having presented his license, registration, and insurance papers, all of which were in order, Mr. Sykes was told to get out of his car and the officer began frisking him. n10 When Mr. Sykes asked him for an explanation, the officer said, "'you can't be too careful. You might have a gun.'" n11 When Mr. Sykes asked why he would have a gun, the officer replied, "'Look, I'm just trying to get home tonight,'" n12 implying that Mr. Sykes might pull a gun out and shoot him. Embarrassment turned to humiliation when, realizing that the over six-foot tall Mr. Sykes would not fit in the patrol car, the officer ordered Mr. Sykes to stand next to the car with his legs spread and arms on the roof, palms down. n13 Just then, Mr. Sykes's conference colleagues drove by in a chartered bus and recognized him, leading some to comment that Mr. [*379] Sykes must have done something wrong for the police to have detained him. n14 Targeting individuals of color perpetuates the stereotype that minorities are more likely than whites to commit crime. Liberals would argue that even if this were true--a dubious proposition itself given enforcement biases n15--it would not excuse applying the stereotype to a particular individual, who may very well be innocent, as Mr. Sykes's story illustrates all too vividly. ADI 2010 10 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Immigration policy in the US is set up to support institutional racism and white supremacy, changing visa policy does nothing

Hing 9, Professor of Law @ UC Davis Bill Ong, “Institutional Racism ICE Raids and Immigration Reform “ University of San Francisco Law Review Fall 2009

The construction of the U.S. immigration policy and enforcement regime has resulted in a framework that victimizes Latin and Asian immigrants. These immigrants of color end up being the subject of ICE raids. They are the ones who comprise the immigration visa backlogs. They are the ones that attempt to traverse the hostile southwest border. Their victimization has been institutionalized. Any complaint about immigrants, fiscal or social, can be voiced in non-racial, rule-of-law terms because the institution has masked the racialization with laws and operations that are couched in non-racial terms. Anti-immigrant pundits are shielded from charges of racism by labeling their targets "law breakers" or "unassimilable." Deportation, detention, and exclusion at the border can be declared race-neutral by the DHS because the system has already been molded by decades of racialized refinement. Officials are simply "enforcing the laws." Like white privilege, institutionalized racism generally goes unrecognized by those who are not negatively impacted. n146 We should know better. The cards are stacked against immigrants of color. The immigration law and enforcement traps are set through a militarized border and an anachronistic visa system. It is no surprise that Latin and Asian immigrants are the victims of those traps. They have been set up by the vestiges of blatantly racist Asian exclusion laws, a border history of labor recruitment like the Bracero Program, Supreme Court deference to enforcement, and border militarization that laid the groundwork for current laws and enforcement policies. ADI 2010 11 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality This resolution does nothing to resolve the structural racism inherent in American Immigration policies and enforcement

Johnson in 2009, Dean, University of California, Davis, School of Law, and Mabie-Apallas Professor of Public Interest Law and Chicana/o Studies [Kevin R., Law and Contemporary Problems, Fall, 72.1, pp. 15-16

Several salient aspects of immigration law have disparate racial impacts. Express bars on the admission of certain races of noncitizens mar this nation's otherwise-proud immigration history. The Chinese exclusion laws and the national-origins quota system disfavoring immigration from southern and eastern Europe, serve as striking examples that the nation today views as indefensible and embarrassing chapters of U.S. history. Racial exclusions have evolved into new and different devices that have racially disparate effects on prospective immigrants to the United States. Consequently, race remains central to the operation and enforcement of U.S. immigration law. n78 Combined with such class-based exclusions as the public-charge exclusion and per-country ceilings, many other devices serve to disproportionately deny people of color from the opportunity of lawful admission into the United States. n79 The limited opportunities for unskilled noncitizens to secure employment visas tend to disproportionately affect people from the developing world (many of whom are people of color), as well. n80[*16] Moreover, race-based enforcement historically has been endemic to U.S. immigration law. n81 This continues to be true today. People of color dominate the populations of both legal and undocumented immigrants to the United States. n82 They are disparately affected by the various exclusion grounds in the U.S. immigration laws and frequently experience roadblocks to their lawful admission to the United States. n83 Not coincidentally, people of color in recent years consistently have been disproportionately represented among the hundreds of thousands of noncitizens deported annually from the United States. n84 ADI 2010 12 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link: Work Visa

Work Visa are used as a way to smuggle modern day black slaves into the country

Bales and Soodalter 9, President of Free the Slaves and American History Professor Kevin and Ron, The Next Door Slave: Human Trafficking and Slavery in America Today pg 22

Every year, foreign diplomats, as well as U.S. citizens and employees of such international agencies as the World Bank and the United Nations, legally import thousands of domestics, who are assigned work visas. Most are brought here from various parts of Africa and India; many are enslaved. The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) doesn’t include household workers in its defi nition of “employees.” This, in combination with an immigration policy that ties the domestic to her employer via her visa, works in the slaveholder’s favor and places in jeopardy any domestic who tries to escape. If he abuses her and she attempts to flee, she leaves herself open to deportation— unless she can prove abuse—since she has broken her contract, which can void the provisions of her visa. Should the case become public, as with Lakshmi, a foreign diplomat can simply claim immunity. In Lakshmi’s case, the diplomat was transferred out of the country, and the Kuwaiti government stated that there would be no investigation. “I guess she just wanted to stay here in the States,” said a Kuwaiti offi cial. “You only see such cases in countries where they see a good opportunity.”4 ADI 2010 13 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Selective prosecution of visa violations leave immigrants unprotected once they are in the country

Bales and Soodalter 9, President of Free the Slaves and American History Professor Kevin and Ron, The Next Door Slave: Human Trafficking and Slavery in America Today pg 67

This view, say representatives of the DOJ, is unduly harsh and not very realistic. One U.S. attorney presents a practical explanation: “I think it has less to do with ‘one version of traffi cking is worse than another,’ than with what could just be a lack of resources. We have to make tough calls about the types of cases we’re going to follow through on. Because of the diffi culty in proving many of these cases, my guess is, law enforcement may be going after the worst ones.”62However, as experience has shown, in cases that the federal government chooses not to pursue, a civil suit can actually succeed. In a civil case, where the burden of proof is less rigid, the plaintiff can sue all the way up the ladder, to the CEO of the corporation that hires the contractor, as well as the contractor himself. A case currently in the Connecticut courts comes out of what had all the earmarks of a traffi cking situation. A dozen Guatemalans were given legal work visas to plant trees in North Carolina; the contractors, however, allegedly packed them into a van, drove them to a nursery in Granby, Connecticut, confi scated their papers, and threatened them with arrest and deportation. According to the civil charges, they were forced to work eighty-hour weeks for practically no pay, denied emergency medical care, and clearly kept against their will.63 U.S. attorney Kevin O’Connor maintains that this situation does not represent a traffi cking case, and the government has decided not to pursue it.64However, Yale University’s clinical professor of law Michael Wishnie and four of his students brought civil suit on behalf of the workers, against not only the labor contractor (Pro Tree Forestry Services of North Carolina) but the grower (Imperial Nurseries) and the corporation that owns them (Griffi n Land and Nurseries), personally naming the parent company’s CEO, among others. Griffi n trades on NASDAQ, and Imperial Nurseries is ened on their fi elds, and they profi ted from the fact that these workers weren’t paid.”65 Regarding Wishnie’s civil suit, U.S. attorney O’Connor says, “We’re perfectly fi ne with Mike going ahead with his suit; it’s not an issue.”66 ADI 2010 14 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link: High Skilled Workers

Even if the number of work visa was increased low skilled people of color would still be excluded

Aoki and Johnson, 2009, Law Professors at UC Davis School of Law Keith and Kevin, “Latinos and the Law Cases and Materials The Need for Focus in Critical Analysis” Harvard Latino Law Review, vol. 12, 73

Scholars, as well as many employers, have long expressed concern with the number and type of employment visas available under the U.S. immigration laws. One common criticism is that the numerical limits and various other requirements for immigrant visas based on employment skills are not adequately calibrated to the nation's need for labor. n70 Importantly, the limited employment visas available under the Immigration & Nationality Act are much more plentiful for highly-skilled workers than for moderately-skilled and unskilled ones. Indeed, few legal avenues are open for unskilled workers without relatives in the United States to lawfully immigrate [*14] to this country. n71 To put it succinctly, "one critique of the entire [American] immigration system is ... that low-skilled workers, as a practical matter, do not have an avenue for lawful immigration to the United States, either temporarily or permanently." n72 Consequently, many low-and moderately skilled workers cannot lawfully migrate to the United States unless they are eligible for family visas (and then still must overcome the public- charge exclusion). As a result, many are tempted and in fact do enter or remain in the country in violation of the U.S. immigration laws. To make matters worse for the undocumented immigrants who circumvent the law, they often find themselves laboring in a secondary labor market - often without legal protections - for low wages and in poor conditions. n73 Even skilled workers often find it difficult to secure visas for which they are eligible under the U.S. immigration laws. n74 The complexities and delays in the process of certification by the U.S. Department of Labor - certification that granting the visa will not adversely affect American workers - necessary for a number of employment visa categories, as well as the potential for abuse, have been the subject of sustained criticism. n75 Microsoft CEO Bill Gates regularly testifies before Congress about the difficulties experienced by high tech employers seeking to bring skilled immigrant workers to the United States. n76 [*15] Even so, the bulk of the employment visas under U.S. immigration laws are for highly skilled workers; visas are also available to investors willing to make a substantial financial commitment in the United States. This disproportionately excludes low-and moderately skilled workers from the developing world, who generally are not eligible for employment visas but who nonetheless desire to pursue economic opportunities in the United States. The lack of lawful avenues for workers to migrate helps to explain the continuing flow of undocumented immigrants to this country. It also helps explain the persistent complaints by mainstream business leaders and organizations such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, about the difficulties of bringing skilled workers to this country, as well as frequent advocacy for guest-worker programs by employers that would allow unskilled laborers to lawfully enter and temporarily work in the United States. n77 ADI 2010 15 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality

Work visa policy has structural racism embedded in its functionality

Aoki and Johnson, 2009, Law Professors at UC Davis School of Law Keith and Kevin, “Latinos and the Law Cases and Materials The Need for Focus in Critical Analysis” Harvard Latino Law Review, vol. 12, 73

For example, U.S. immigration law on its face discriminates against poor immigrants, with rarely a reservation raised; n37 in contrast, ordinary U.S. domestic law cannot infringe upon the right of poor citizens to travel (at least domestically). n38 Immigration law has permitted race and class to operate in ways that are truly extraordinary in U.S. law - almost always to the detriment of immigrants. n39 The reason is the plenary-power doctrine, which remains the law of the land even though the Supreme Court forged it out of whole cloth initially to shield blatantly discriminatory laws from judicial review. n40 The doctrine creates a deep and wide gulf between ordinary constitutional law and the constitutional law of immigration. n41 The Court continues to invoke a doctrine n42 [*8] that academics, who contend that ordinary constitutional principles should apply to the review of the U.S. immigration laws as they generally do to other bodies of law, most simply love to hate. n43 The bottom line is that the proverbial deck is stacked against potential immigrants from the developing world. U.S. immigration law presumes that "aliens" cannot enter the United States and the burden is on the noncitizen to defeat the presumption and establish that all of the eligibility requirements for a visa have been satisfied. n44 Available immigrant visas are generally directed toward noncitizens with family members in this country and toward highly skilled workers. n45 Various exclusions and other features of U.S. immigration law make it difficult for noncitizens of limited education and moderate means from the developing world - even if eligible for a family, employment, or other immigrant visa - to immigrate lawfully to the United States. n46 Due to the plenary-power doctrine, the courts let all such laws stand. ADI 2010 16 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link: H-2 Work Visa

H-2 Visa are used as a way to oppress people of color under the guise of a government program for workers.

Bales and Soodalter, 9, President of Free the Slaves and American History Professor Kevin and Ron, The Next Door Slave: Human Trafficking and Slavery in America Today pg 70-71

It’s bad enough when slavery exists and the government is either unaware or unwilling to address it. But how about an ongoing federal program that makes it much too easy to bring people into the United States to be enslaved? Welcome to the “Guest Worker Program,” also known as the H-2program, after the type of visas assigned. Temporary agricultural workers from Latin America, Asia, eastern Europe, and the Caribbean are lured here by the offi cial guaranteeof good working conditions: so many hours a week at a fi xed and acceptable wage, government- inspected living conditions, and medical benefi ts, including “payment for lost time from work and for any permanent injury.” Guest workers are also entitled to “federally funded legal services for matters relating to their employment.” According to the rules, any employer who receives DOL approval to import guest workers must compensate them for their travel expenses—the plane or bus fare and food costs incurred on the way to the promised job. Finally, the worker is guaranteed three- fourths of the total hours promised in his contract for the period of employment specifi ed.71The conditions of the program also stipulate that the worker is obligated to stay with the employer who sponsored him; he cannot leave to seek a job elsewhere. Some employers adhere to the conditions of the law. But in a large number of cases, not a single one of these promises is honored because of employer abuses and government neglect. The Guest Worker Program is not a new concept: the United States has been taking in foreign workers almost since its inception. Our attitude toward them—at least over the last hundred years—has been ambivalent. America welcomed them when we needed them—during the two World Wars, for example, when most of the permanent work- force was in the service —and limited or simply ousted them when we didn’t. In 1943, to provide workers for the southern sugar cane fi elds, the government established the H-2program. From its beginning it was characterized by inequity and brutality. As recently as 1986, cane cutters who attempted a work stoppage over poor conditions were beset by armed police with dogs, acting at the employers’ behest. The incident became known as the “Dog Wars.” In that same year, the H- 2program was expanded to include nonagricultural workers, but the number of mainly Asian and Latin American guest workers arriving for farm work under the program is still signifi cant. The number of foreign workers certifi ed by DOL as agricultural—or H-2A—laborers went from forty- eight thousand in 2005to nearly seventy-seven thousand in 2007.72 The viability of a guest worker program has been endlessly debated, but one thing is clear: its lack of oversight provides a splendid opportunity for mistreatment and enslavement. In the words of Mary Bauer of the Southern Poverty Law Center, “The very structure of the program... lends itself to abuse.”73Increasingly, employers use labor contractors to recruit guest workers for them. In this way they avoid technical responsibility for the workers, legally distancing themselves from any abuses that follow. The brokers recruit the workers in their home countries. Unrestricted by law or ethics, they make promises of work and wages that far exceed the provisions of the program—so much so that the workers go into massive debt, often in excess of $10,000, to pay the recruiter’s infl ated fee. Employers often bring in more workers than they need. They exaggerate the number required, as well as the period of employment, since they know the government isn’t paying attention. Employers know they can get away with not paying the three-fourths of the wages or meeting the other conditions the contract stipulates. The worker, heavily in debt and doomed to few work hours and pay fraud, is indentured even before he leaves home. When he arrives in America, he fi nds himself at the mercy of his employer. The promised forty-hour week turns out to be only twenty-fi ve hours, and his looming debt becomes instantly insurmountable. Sometimes the workweek is eighty hours long, but the promised pay is withheld or radically reduced. The “free housing in good condition” can turn out to be a lightless, heatless shack with no bed or blankets, and sometimes no windows to keep out the cold, shared with twenty or thirty other workers. In some cases, he is locked in or kept under armed guard.74If transportation to the job is required, a travel fee is deducted from his pay. Fees are illegally charged for food and sometimes rent, both of which are guaranteed him by law. The pro- gram also promises him worker’s compensation for hospital or doctor’s costs and lost wages, but the moment he gets sick or hurt on the job he fi nds this is a lie. Ignorant of the system and the language, he has no clue how to seek medical help, and his employer, far from being solicitous in the face of losing a laborer, pushes him to keep working. To enforce control, the employer confi scates or destroys the guest worker’s passport and visa, making him an illegal alien. In this way, he faces ADI 2010 17 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality the threat of arrest and deportation should he attempt to leave or refuse to work. If he manages to escape and fi nd his way to the local police, the likelihood of the authorities taking the word of an undocumented migrant worker, with little or no English, over that of an established local grower is slim to none. Without his papers, the worker is at considerably greater risk than his employer. And once he has made waves, he runs the risk of being blacklisted and destroys any chance of coming back in the future for a decent job.75The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace reported in 1999,“Blacklisting of H-2A workers appears to be widespread, is highly organized, and occurs at all stages of the recruitment and employment process.”76 The large North Carolina Growers Association has blatantly kept a blacklist, which in 1997was titled “NCGA Ineligible for Rehire Report,” listing over a thousand workers’ names.77 All in all, there is little about this that doesn’t fall under the defi nition of slavery. Workers are often kept against their will, held by the threat of violence, paid as little as their employers wish, and denied every basic right guaranteed by law. In fact, there is little to distinguish these thousands of guest workers from the crews held in slavery by Miguel Flores—except for the stunning fact that this particular form of bondage occurs within a government-sponsored program. Admittedly, this scenario doesn’t play itself out in every instance: many employers honor the conditions of the H-2A laws, providing the work promised at the agreed-upon wage. Nonetheless, this doesn’t change the fact that because of the program’s lack of oversight the result can be coercion and peonage. ADI 2010 18 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link: Link of Omission Key

LINK OF OMISSION IS PRECISLY THE POINT

White social practice of not discussing whiteness is disturbing. Absence is as important as presence in evaluating symbolic action

NAKAYAMA & KRIZEK in 1995 Asst Prof, Dept of Communication @ Arizona State Univ. and Asst Prof, Dept of Communication @ St. Louis Univ. Thomas K. -& Robert L.“WHITENESS: A Strategic Rhetoric” Quarterly Journal of Speech, 81, 291-309

Thus, the “white” social practice of not discussing whiteness is especially disturbing. Sleeter explains: “I suspect that our privileges and silences [about whiteness] are invisible to us [whites] partly because numerically we constitute the majority of this nation and collectively control a large portion of the nation’s resources and media, which enable us to surround ourselves with our own varied experiences and to buffer ourselves from the experiences, and the pain and rage of people of color” (6). Within the context of academic writing that silences whiteness, what kinds of power relations are reproduced within our own discipline? McKerrow, in one of his principles of critical rhetoric, notes that “ absence is as important presence in understanding and evaluating symbolic action” (“Theory and Praxis” 107). In what ways and under what conditions does the silencing of whiteness, its presumed understanding, reproduce communication interactions between and among whites? Do our academic practices and publications reinforce these white communication practices by not interrogating whiteness? As we have shown above, whiteness is a complex, dynamic, and power-laden assemblage that remains elusive. And, as Volosimov has noted, the ideological sign is always already multi-accentual. To assume that readers of communication scholarship already understand the multi-accentuality of whiteness is a mistake, for it presumes a white audience. “White” here is ideological, as one must play the white game, it does not require that one be “white”-discursively or scientifically. ADI 2010 19 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link: Soft Left Policies / Critical Affs

Critical theory is divorced from material reality – This will only maintain whiteness. Only a critique that is attentive to identity can transform social reality

Young 90, professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago (Iris Marion, Polity and Group Differences) August 17, 1990 . Rejecting a theory of justice does not entail eschewing rational discourse about justice. Some modes of reflection, analysis, and argument aim not at building a systematic theory, but at clarifying the meaning of concepts and issues, describing and explaining social relations, and articu lating and defending ideals and principles. Reflective discourse about jus - tice makes arguments, but these are not intended as definitive demonstra tions. They are addressed to others and await their response, in a situated political dialogue. In this book I engage in such situated analysis and argument in the mode of critical theory.

As I understand it, critical theory is a normative reflection that is histor ically and socially contextualized. Critical theory rejects as illusory the effort to construct a universal normative system insulated from a particular society. Normative reflection must begin from historically specific circumstances because there is nothing but what is, the given, the situated interest in justice, from which to start. Reflecting from within a particular social context, good normative theorizing cannot avoid social and political description and explanation. Without social theory, normative reflection is abstract, empty, and unable to guide criticism with a practical interest in emancipation. Unlike positivist social theory, however, which separates social facts from values, and claims to be value neutral, critical theory denies that social theory must accede to the given. Social description and explanation must be critical, that is, aim to evaluate the given in normative terms. Without such a critical stance, many questions about what occurs in a society and why, who benefits and who is harmed, will not be asked, and social theory is liable to reaffirm and reify the given social reality.

Critical theory presumes that the normative ideals used to criticize a society are rooted in experience of and reflection on that very society, and that norms can come from nowhere else. But what does this mean, and how is it possible for norms to be both socially based and measures of society? Normative reflection arises from hearing a cry of Normative reflection arises from hearing a cry of suffering or distress, or feeling distress oneself. The philosopher is always socially situ ated, and if the society is divided by oppressions, she either reinforces or struggles against them. ADI 2010 20 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link: Poverty Advantages

Poverty Cannot Be Isolated From Race – Whiteness Structures The Spaces Impoverished People Can Live And Encourages Future Exclusions

Johnson 95, Perre Bowen Professor of Law and Thomas F. Bergin Research Professor of Law at the University of Virginia School of Law. Alex M., Jr. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, May, 1995 http://www.jstor.org/stable/3312487

In a world in which the poor have fewer choices because of their necessitous economic situation, one would expect that the socioeconomic status of the poor, both white and black, would consign them to live in relatively integrated, "poor" communities in which the only defining characteristic of the inhabitants is poverty. As Part III details, however, an examination of the data reveals that the poor are more likely to live in segregated communities than those who are economically advantaged. Indeed, it is my hypothesis that Blacks will encounter less discrimination and racism as they achieve higher degrees of economic status.'8 In this context, money or socioeconomic status has an impact on the degree of segregation experienced by Blacks . Poverty , then, serves a dual role in the maintenance of Black segregated communities . First, poverty and all that it entails'9 reinforces negative racial stereotypes of Blacks by whites and leads to efforts to exclude and separate . Second, the poverty experienced by whites causes them to value the only significant attribute they possess-the property right in their are well-known for the selectivity that they apply in approving or rejecting prospective tenants. ADI 2010 21 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link: Illegal Immigration Advantages

Claims to solve for illegal immigration always devolve to debate about solving for Mexican migration

Hing 9, Professor of Law at UC Davis Bill Ong “Institutional Racism ICE Raids and Immigration Reform “ University of San Francisco Law Review Fall 2009

Rightly or wrongly, today the so-called "illegal immigration" problem has become synonymous with the control, or lack thereof, of the [*326] southwest border. As such, the "problem" is synonymous with Mexican migration, and Mexican immigrants have come to be regarded by many anti-immigrant voices as the enemy. The anti-immigrant activists do not regard themselves as racist; they view themselves as the voice for law and order. The history of the border, labor recruitment, and border enforcement explains how the institutionalization of anti-Mexican immigration policies have created the structure to allow these voices to claim racial and ethnic neutrality and for many Americans to accept that claim. 1. Migration Between 1848 and the 1960sGerald Lopez provides a clear picture of the historical relationship between Mexican migration and the United States. n81 Long before the North American Free Trade Agreement ("NAFTA") and terms like globalization or transnationalism were in vogue, Mexicans and Americans were living the reality of interconnected economies and societies. The southwest border essentially became an open border in 1848, when the United States forced Mexico to sign the Treaty of Guadalupe. The United States gained California and New Mexico (including present-day Nevada, Utah, and Arizona) and recognition of the Rio Grande as the southern boundary of Texas. n82 This amounted to fifty-five percent of Mexico's former territory. The treaty gave all Mexicans living in the ceded territory the option of becoming U.S. citizens or relocating within Mexican borders. In the years immediately following the treaty, many Mexicans thought of the territories as part of Mexico. n83 "Mexicans and Americans paid little heed to the newly created international border, which was unmarked and wholly unreal to most." n84 ADI 2010 22 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Link Magnifier: Skepticism

Approach Their No Link Arguments With The Highest Degree Of Skepticism – Whiteness Assures That The Critique Of Race Is Always Sidelined. History Proves That This Denial Works In Service Of White Supremacy

Wise, 2009, antiracist activist, essayist and father (Tim, Color-Blind, Power-Oblivious: Eric Holder and the Whitewashing of Racism http://www.redroom.com/blog/tim-wise/color-blind-power-oblivious-eric-holder-and-whitewashing-racism

Sadly, whites are rarely open to what black and brown folks have to say regarding their ongoing experiences with racist mistreatment. And we are especially reluctant to discuss what that mistreatment means for us as whites: namely that we end up with more and better opportunities as the flipside of discrimination. After all, there is no down without an up, no matter how much we'd like to believe otherwise.

It is white denial, as much as anything, which has allowed racial inequity to persist for so long, and it's nothing new. In the early 1960s, even before the passage of modern civil rights laws, two out of three whites said blacks were treated equally, and nearly 90 percent said black kids had equal educational opportunity. Matter of fact, white denial has a longer pedigree than that, reaching back at least as far as the 1860s, when southern slave-owners were literally stunned to see their human property abandon them after the Emancipation Proclamation. After all, to the semi-delusional white mind of the time, they had always treated their slaves "like family."

Until we address our nation's long history of white supremacy, come to terms with the legacy of that history, and confront the reality of ongoing discrimination (even in the "Age of Obama"), whatever dialogue we engage around the subject will only further confuse us, and stifle our efforts to one day emerge from the thick and oppressive fog of racism. For however much audacity may be tethered to the concept of hope, let us be mindful that truth is more audacious still. May we find the courage, some day soon, to tell it. ADI 2010 23 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Internal Link: Color Blindness Bad

Making the legal advantages of Whites seem neutral is a crucial part of interest convergence

Stec 7, J.D. expected fall 2006, University of Minnesota Law School; M.P.P. expected Spring 2007, University of Minnesota, Humphrey Institute (Justin, Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy, The Deconcentration of Poverty as an Example of Derrick Bell's Interest-Convergence Dilemma: White Neutrality Interests, Prisons, and Changing Inner Cities, 2007, http://www.law.northwestern.edu/journals/njlsp/v2/n1/2/)

The interest-convergences dilemma does not say that white interests, and white interests alone, will be expanded, while black interests are wholly suppressed. Instead, the phenomenon is dilemmatic because white interests will supercede black interests through time, and efforts to help blacks will also work to further solidify white interests. The process is subtle; white interests will not be adequately exposed, operating in a neutral way, through different avenues than overt racism. The important aspect of interest-convergence to apply to deconcentration policies is the exposure of white interests in the process. ¶ 27Whiteness itself is not and will not be defined in an overtly racialized manner. White posturing instead holds onto a version of color-blindness toward its own privilege. Bonnie Grover writes that "white[ness] is transparent. That's the point of being the dominant race. Sure, the whiteness is there, but you never think of it. If you're white, you never have to think of it." 44 As whiteness has been institutionalized into a means of residential success 45 it has mutated into an economic forum—it can be equated with property interests and even property itself.46 Operating as such, multiple arenas that might typically involve race stigma have been castigated or removed from racial context precisely because they are fundamentally raced as white. "Racing" as white is likewise synonymous with a de-racializing generally because it changes the way in which race is conceived. De-racing provides that one can and should come out of a group-based status and supplant it with an individual ethos that stresses merit progress toward realizable and concrete goals. This is not to deny that whites operate as a group through individual actions (nor through economic actions), but instead to say that the justificatory mechanisms available to whites rely precisely on the appeal to a non-racial standpoint. Such a non-racial standpoint is important for groups that hold power because it does not allow them to be viewed as groups but works to maintain the group-based power nevertheless. ¶ 28 In this sense, whiteness performs a rhetorical and theoretical link to an apolitical standpoint, one that can decapitate conflict and promote permanent and numerous social constructions that then work to perpetuate inequality, even when seen as a salve, and even when actually helping those upon which oppression depends. If we accept Bell's logic that races cannot operate unilaterally without affecting each other in racialized ways, it is important to expand on potential white interests in deconcentration programs. This section aims to begin that project. In Section III, I will trace the linkages of white interests and property through the contact point of the prison system. Please keep in mind that the white reasoning I am particularly concerned with relies fundamentally on a spatial disassociation—relatively rigid segregation—that was explicated in the last section. Deconcentration programs may actually prove to further this kind of exclusion, enabling justification for affluent white solidification. Like Bell's ideas in relation to Brown, these are normative and symbolic points that have material consequences. ADI 2010 24 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality

The idea of “equal” and “color-blind” law is the new era of racism evolving around past strategies to form a racial hegemony

Bond 3, Visiting Associate Professor of Law and Assistant Director, International Women's Human Rights Clinic, Georgetown University Law Center (Johanna E., Emory Law Journal, 52 Emory L.J. 71, “International Intersectionality: A Theoretical and Pragmatic Exploration of Women’s International Human Rights Violations”, Winter 2003, Lexis Nexis.)

First, it cannot grasp the processual and relational character of racial identity and racial meaning. Second, it denies the historicity and social comprehensiveness of the race concept. And third, it cannot account for the way actors, both individual and collective, have to manage incoherent and conflictual racial meanings and identities in everyday life. 206 According to Winant, the civil rights movement transformed the nature of racial subordination in the United States from "racial domination" to "racial hegemony." 207 Prior to the civil rights movement, the period of racial domination included overt and coercive racist methods such as segregation and lynching. After the civil rights era, during which the idea of equality, at least in theory, took hold, opponents were forced to find more covert ways of maintaining white supremacy. Racial hegemony emerged as a result. Conservatives accepted the notion of "equality" but co-opted it and recast it in support of a conservative, "color-blind," anti- affirmative action ideology that failed to acknowledge that a history of race-conscious discrimination [*122] necessitates race-conscious remedial measures. 208 ADI 2010 25 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Colorblindness obfuscates the racism that has disadvantaged minorities for centuries by giving the appearance that such oppression doesn’t exist

Breshears, 02, former assistant instructor, communication studies, U Texas Austin, (David, "One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: The Meaning of Equality and the Cultural Politics of Memory in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke," 2002, Journal of Law in Society 3, Winter, 67-103, Lexis)

There is a growing body of scholarship dedicated to assailing defenders of colorblindness "for their complicity in maintaining the power of an edifice known as 'whiteness.'" n29 Scholars from a variety of academic disciplines have demonstrated the connection between the principle of colorblind equality and the persistence of white privilege. Legal scholars have challenged the principle of colorblindness by reestablishing its history as the legacy of white supremacy. Colorblindness demands race-neutral criteria to determine the distribution of governmental n30 goods and services, application of legal [*76] penalties and protections, the availability of employment and educational opportunities, and the accessibility of public programs and facilities. However, the "race-neutral" legal standards that guide decision making under the regime of colorblind equality - merit and individualism - are remnants of a period of "explicit racism," and therefore are inevitably marked by the residue of racial privilege. n31 According to legal scholar Gary Peller, colorblindness is premised upon "objectivity, rationality, and neutrality," standards of judgment that "justify racial domination - if not to its victims then at least to white beneficiaries who need to believe that their social positions result from something more than the brute fact of social power and racial domination." n32 As such, exclusionary criteria masquerade as objective measures of success, and the legacy of white privilege is rendered invisible. Under the guise of these apparently race-neutral standards, the material benefits of whiteness accruing from generations of legal, political, social and economic exclusion of non-whites, continue to accumulate in the pockets of white folk. Law Professor Jody Armour refers to this invisible legacy of privilege as the "glaring lacuna in anti-affirmative action rhetoric." n33 He [*77] argues that the forms of preferential assistance that disproportionately benefit white males constitute a vast, but unacknowledged, Antarctic of white affirmative action. n34 This "old boy network" includes membership in social and fraternal organizations, practices such as nepotism and cronyism, legal institutions such as inheritance and antimiscegenation laws, as well as the more visible signs of racism, such as prejudicial stereotypes of African-American students and workers. n35 This point is significant, for as both Armour and Peller note, defenses of affirmative action are most commonly framed in the rhetoric of restitution or promotion of diversity. What Armour suggests is that affirmative action is not simply a remedy for past discrimination, or for the promotion of diverse perspectives in an otherwise racially and culturally homogenous environment (although, these goals are certainly not discounted), but is instead a mechanism by which this invisible network of white affirmative action may be disassembled. n36 Armour draws upon empirical research to prove that, "far from being color-blind, post-civil rights America is rife with discrimination against marginalized groups." n37 The empirical data shows that the concept of merit is not truly objective and can never account for the persistent effects of a legacy of cultural, economic, and political exclusion. n38 [*78] Individualism and merit are not racially neutral measures of achievement - the antitheses of (racial) collectivism and (racial) preference. Rather, individualism is an effect of the invisibility of (white) collectivism, and merit is an effect of the invisibility of (white) preference. Colorblindness, therefore, is little more than a denial of the advantages gained and maintained by these racially coded constitutive values . I place my project in the context of these scholarly investigations of the connections between colorblindness, individualism, merit, and "whiteness" to suggest that it is ADI 2010 26 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Impact: White Supremacy

White supremacy makes wars, violence, and genocides inevitable

Daniels 09, writer, for over thirty years of commentary, resistance criticism and cultural theory, and short stories with a Marxist sensibility to the impact of cultural narrative violence and its antithesis, resistance narratives in American Literatures, with a specialty in Cultural Theory (race, gender, class narratives) from Loyola University, Chicago (Lenore Jean, PhD, U.S. Corporate-Militarist Government Motto: Oppress the Dialogue on White Supremacy - Oppress the Rage of Oppressed People Represent Our Resistance, April 2, 2009, http://www.phillyimc.org/en/us- corporate-militarist-government-motto)

White supremacy, bell hooks explains “evokes a political world that we can all frame ourselves in relationship to; the ideology of white supremacy allows for the collusion of black people with the forces of racism; it refers to an institutional structure and not individual beliefs.” White supremacy means, hooks writes in Killing Rage, “talking about imperialism, colonialism…genocide…the white colonizers’ exploitation and betrayal of Native Americans. [It’s] about ways the legal and governmental structures of this society from the Constitution on supported and upheld slavery, apartheid.” Today an “all- pervasive white supremacy,” hooks explains, is in this society an ideology and behavior. “Folks will insist that they are not racist, and then simultaneously argue that everyone knows property values will diminish if too many black people enter the neighborhood,” writes hooks in Class Matters. “Black people,” she writes in Killing Rage, “working or socializing in predominantly white settings whose very structures are informed by the principles of white supremacy who dare to affirm blackness, love of black culture and identity, do so at great risk.” White supremacy speaks to a structure of racist domination and oppression. The conservative and liberal commitment to white supremacy permits the huge discrepancies in quality of life between white and Black Americans. White supremacy is about the way foreign policy and capitalism are controlled by the fraternity of men on Wall Street and in Washington and how that policy of “free-trade,” torture, rendition, regime change, invasion for material resources builds capital for corporations which in term maintains a system dependent on oppressing the many, the majority of the Earth’s planet. ADI 2010 27 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Impact: Whiteness

Whiteness Is The Sticking Point Between Two Forms Of Oppression – It Encourages Internal Colonization In The Form Of Ghettos, Urban Spaces, And Segregation While Simultaneously Promoting External Imperialism White 7, Associate Professor of Political Science at Ohio University specializing in political theory, feminist ethics, and public policy Julie Anne,“The Hollow and the Ghetto: Space, Race, and the Politics of Poverty,” Politics and Gender 3:0202, 271-280

I begin with a piece from Charles Mills’s The Racial Contract (1997,41–42): “The norming of space is partially done in terms of the racingof space, the depiction of space as dominated by individuals of a certain race. At the same time, the norming of an individual is partially achieved by spacing it, that is, representing it as imprinted with the characteristics of a certain kind of space.” He continues, “Morally vice and virtue are spatialized” (p. 46). Mills and, more recently, Uday Mehta (1999) have noted that, historically, the contrast between civilized, white, European spaces and wild, savage spaces is used to justify imperial expansion and to reconcile the seemingly irreconcilable: the humanist universalism of liberalism and liberal states, and the colonizing practices of empire. Such practices often involved forced conversion, segregation, enslavement, genocide, the dismantling of indigenous traditions, particularly family and religious institutions, and the creation and state enforcement of new or previously meaningless ethnic divides—frequently by states expressly committed to human rights and equality. In the 1960s, as former colonies were gaining their independence, there were those within both academic and activist circles who turned to internal colonialism to describe the black experience in the United States. Some focused on understanding the American ghetto as a colony chiefly in the economic sense—that is, a geographically isolated and exploited labor market. Others placed greater emphasis on colonization as the practice of shaping the consciousness and reshaping the culture of the colonized. But both approaches found sympathizers. Similar arguments were made, though almost exclusively by academics, in the Appalachian context. Certainly, where colonialism is understood spatially chiefly as a practice of exploiting natural resources and labor from one region or territory for profits to be reaped by a distantly located class of owners, the colonial model applies well. It has always been the case and it remains so that despite the tremendous market value of natural resources, particularly of coal, few in the region who mine it see the profits. Appalachia remains by virtually every measure one of the poorest regions in the country. Left unchecked, whiteness will take over every aspect of the lifeworld.

Sullivan 8, Associate Professor of Philosophy and Women’s Studies at Penn State U (Shannon, "Whiteness as Wise Provincialism: Royce and the Rehabilitation of a Racial Category." Transactions of the Charles S. Pierce Society: A Quarterly Journal in American Philosophy 44.2 (2008): 236-262. Project MUSE.)

This advice is especially appropriate for the development of a wise form of whiteness since whiteness has a long history of oppressing through exclusive possession. Analyzing the attempts of white nations [End Page 249] in World War I to divide up and exploit “darker nations,” for example, Du Bois declares that whiteness is nothing less than “ ownership of the earth.” 26 White people have appropriated the gifts of African Americans, ignoring the economic, military, political, spiritual, and other contributions that black people made to the building of the United States. They also have usurped the land of Native Americans because of Native Americans’ allegedly inappropriate use of (read: failure to appropriate) it.27 Even more to the point, whiteness has defined itself through exclusive ownership of values such as goodness, cleanliness, and beauty. Other races, by comparison, tend to be characterized as the opposite: bad, dirty, and unattractive. Whiteness’s definition through opposition to a non-white other means that if whiteness possesses a particular value, then other races cannot. ADI 2010 28 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Impact: Structural Racism

With or without visa, people of color are not protected from discrimination

Hing 9, Professor of Law at UC Davis Bill Ong, “Institutional Racism ICE Raids and Immigration Reform “ University of San Francisco Law Review Fall 2009

This Article argues that the structure of immigration laws has institutionalized a set of values that dehumanize, demonize, and criminalize immigrants of color. The result is that these victims stop being Mexicans, Latinos, or Chinese and become "illegal immigrants." We are aware of their race or ethnicity, but we believe we are acting against them because of their status, not because of their race. n6 This institutionalized racism made the Bush ICE raids natural and acceptable in the minds of the general public. Institutionalized racism allows the public to think ICE raids are freeing up jobs for native workers without recognizing the racial ramifications. n7 Objections to ICE raids and the Border Patrol's Operation Gatekeeper are debated in non-racial terms. However, not viewing these operations from an institutionalized racial perspective inhibits the total revamping of our immigration system that needs to take place.

Part I begins with a description of selected ICE raids. Part II follows with a discussion of the institutional racism that is grounded in the history of U.S. immigration laws and policies. Part III explains how [*310] the racial history of immigration policy has become institutionalized so that seemingly neutral policies actually have racial effects. Understanding the historical underpinnings of race-driven immigration policy offers a broader range of solutions to current policy and enforcement challenges. Recognizing the racist nature of the system allows for a framework to remedy a racist system. ADI 2010 29 Fellows Lab-Kirkman Critical Racial Reality Structural violence is perpetuated by the racist views underlying the 1ac. This outweighs all other impacts and turns case. Aff deepens the inherent structural violence of society by partaking in racism. Mumia ’98, political prisoner who in his chosen role as a journalist has for a lifetime supported the aspirations and struggles of working class and oppressed people. (Abu-Jamal, Column Written 9/19/98 http://www.mumia.nl/TCCDMAJ/quietdv.htm)