1

Miranda Holmes 10/09/13 Rhetorical Analysis 2

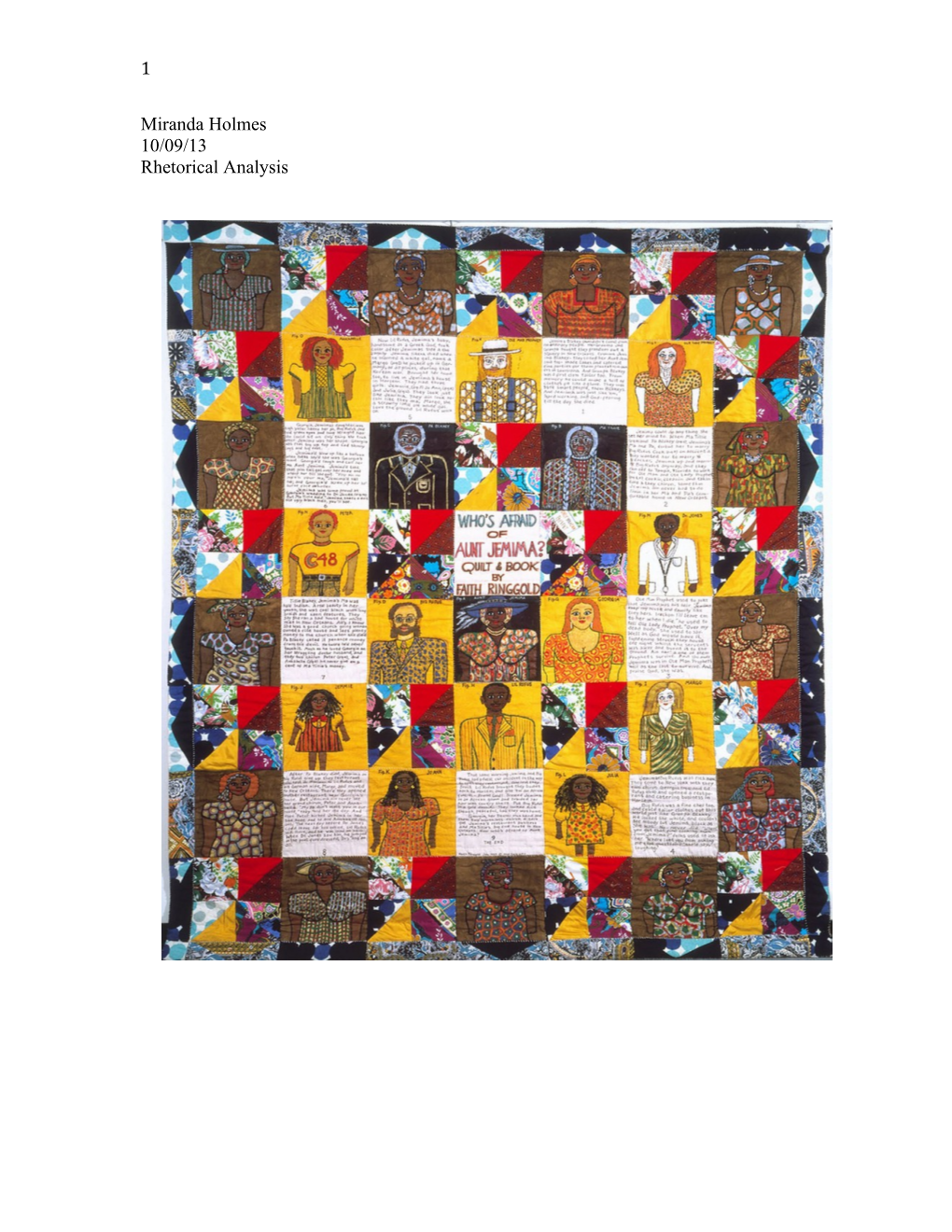

Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?

Emotionally stirring works are rarely found in the form of fabric and stitches.

Less common still are mundane bed sheets that make gender and racial statements. Yet stitched, painted, feminist, and racially argumentative are all adjectives that can describe

Faith Ringgold’s story quilt Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? Through both the story she tells as well as through the visual and material aspects of this piece, Ringgold makes the argument that despite the difficulties black women face in a white-male dominated world, they can still rise up in society and make a name for themselves.

Ringgold grew up in Harlem during the 1930s and 40s with her father and mother, who was a fashion designer. She received her Masters of Arts in 1959, and in the 1970s she became highly involved in feminist and anti-racist organizations (Hale). Since

Ringgold is a black female activist, her works as an artist circulate around the theme of black females in the community and the power that they hold. Her credibility is established through her activist work, making her artistic pieces of much more value. All these elements of her past, including her exposure to fabric textiles through her mother’s work to her participation in activist organizations play major roles specifically in her piece, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?

This work establishes one of the artist’s turning points in her career. It is the first in a series of story quilts she made during the 1980s that deal with feminist and racial issues. During this time, Ringgold was trying to get her autobiography published, but no publishers were interested in her story, so she began to make story quilts illustrating her life (Ringgold, “Biography”). The significance of employing a story quilt to get her message across comes from the history of making quilts: 3

There has been a strong African-American quilt-making tradition, influenced by the weaving done by the men in Africa, and brought to America with the slaves, where women continued the tradition. Quilts in the African-American slave community served various purposes: warmth, preserving memories and events, storytelling, and even as

"message boards" for the Underground Railroad… (Doyle).

By referencing her culture and its heritage as a slave community, Ringgold evokes the idea of passing down the feminine tradition of quilt making, and by doing so, she passes down stories in her community, specifically to women. In her quilts, she conveys stories of discrimination and hardship, but more importantly, of African-

Americans and females overcoming it all. “Preserving memories” is important so that a minority won’t forget their heritage, so that they can build on their past and continue making new stories of hope. Thus, this medium allows the work of art to contain much more than “purely pictorial intentions”; by providing warmth as well as familiar stories to those who use it, the quilt functions to both visually engage and to bind a community

(Doyle). Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? follows in the footsteps of this tradition, providing a sort of family tree, and recounting the story of Jemima, a fictional character whose life relates loosely to Ringgold’s own life.

The story, written in vernacular with uneven lettering, follows the life of Jemima, the daughter of Pa Blakely and Ma Tillie, whose grandparents were freed from slavery.

She falls in love with a white man, Big Rufus, and they elope due to her parents’ disapproval of him. They begin working hard for a wealthy couple, but when the couple dies, Jemima and Big Rufus inherit all of their money, and decide to move to Harlem to open a restaurant. They start a family; their daughter, Georgia, takes after her dad 4 because she has white skin, and their son, Lil Rufus, has black skin. In their old age,

Jemima and Big Rufus die in a car accident and Georgia and her husband inherit the restaurant. The story ends with the line, ‘Now, who’s afraid of Aunt Jemima?’ (Ringgold

1983). Jemima and her family are dressed in luxurious clothing; Jemima is even sporting a grandiose hat and a pearl necklace. Further, there are portraits along the sides of the quilt of well-dressed black women, and it is important to note that all the characters are very cartoonish with broad shoulders, little arms, and blank stares suggesting a childish style. While the written story contains some true elements of Ringgold’s life, it’s mostly fictional; however, the visual aspects of the piece speak strongly to the artist’s ideologies.

Through her use of materials, along with a strong female character, Ringgold makes the statement that despite being dealt with unfair circumstances, black women can still be successful in life. By choosing to make a quilt, Ringgold hints at her own roots since her mother was a fashion designer, but she also makes a deeper statement about society and femininity. Women typically sew and make quilts so they are seen as feminine objects. Further, fabric is not a strong material; it is easily manipulated and pliable. Ringgold contrasts the softness of the material with a strong female character in her story. Since Jemima is black, and her daughter has white skin, she must deal with racial issues: “Jemima’d blow up like a balloon when folks say’d she was Georgia’s maid. Georgia’d laugh and call her ma Aunt Jemima…” to which Jemima responds to her prideful daughter, “‘You ain no more’n your ma’” (Ringgold 1983). Even Jemima’s daughter mocks her about her skin color, calling her “Aunt Jemima”. The significance of this epithet comes from the typical black “mammy” figure popular in early cinematic and literary works. In the early 19th century, black women playing significant parts were 5 almost always placed in servile or domestic roles. One such example is Mammy, played by Hattie McDaniels, in “Gone with the Wind” (Wallace). Even more important is the cultural reference to the figure Aunt Jemima who is the face of a pancake mix and syrup.

Since Aunt Jemima is tied to the domestic task of cooking, she fits the archetypal feminine role of a woman stuck in the kitchen. Even the Aunt Jemima syrup bottle is modeled after a robust, busty, apron-donning, homebody kind of woman, again thrusting the black woman into this eternal role as an obedient yet subservient domestic. When

Georgia ridicules her mother by calling her “Aunt” Jemima, she is at once putting her into this black servile role as the mammy serving her white counterpart, and also exiling her to the kitchen of femininity. Yet, since Jemima puts her daughter in her place, and is depicted as a successful businesswoman dressed in upper-class clothes, Ringgold makes the statement that even though factors, such as a weak material, and a belittling epithet, work against Jemima (the personification of black women) she still beats the odds, embodying the thriving working woman, not the feminine mammy. Here, the title is significant; since Jemima rejects the commonplace role as a “mammy”, do the viewers, possibly white male art critics, fear her power?

The artist’s use of a childish style and color blocking references important historical trends in art, through which Ringgold stresses the inequalities for female artists.

Ringgold blurs the line between “high” art and craft; can quilts be considered museum- worthy pieces, or rather should they be kept in the home hung in the dining room or laid out on a bed? Faith Ringgold painted the figures on canvas and then stitched them into the quilt, so the material was not deterring her from creating a realistic image. Choosing to paint distorted figures with lop-sided shoulders, limp arms, and expressionless faces 6 allowed Ringgold to make a statement about female artists. Non-artists often describe twentieth century art as “irregular” or that “a child could have done that”. Picasso’s famous work, “The Weeping Woman”, for example, is painted with a distorted face, including eyes that are too far up on the forehead, and a nose that is proportionally too large for the face, both “errors” that a child typically makes when painting a portrait.

Since Ringgold and Picasso both paint their figures in a childish way, what makes critics consider Picasso’s piece as high art, and Ringgold’s piece as borderline craft? Here,

Ringgold makes the argument to her audience, which includes art critics (a field dominated by white males), that pieces are considered differently based on the artist’s gender and skin color. Additionally, the similarities between the color blocking patterns on the quilt and the Cubist movement are important to note. Since quilts with blocks and triangles of color have been made by women for centuries, and artists only began exploring Cubism during the 20th century, Ringgold makes the argument that women were creating this blocking effect long before Picasso or Braque. Credited with establishing this technique are not the female quilt-makers, but the male painters. Despite the many points Ringgold makes about the inequality of artists, she still keeps her message hopeful, since in the story component, Jemima rises up in society despite her skin color and gender. Not only is this represented visually, but also the same theme is found in the story Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?

The story component is written entirely in casual vernacular, adding to the idea that black women are born into a society that is often viewed by the dominating class as uneducated, thus showing they must work against the odds to be successful in life. The story follows a family whose ancestors were slaves, and they make their fortune not by 7 going to college, but through hard work in the catering and restaurant businesses.

Sentences are written in a choppy, conversation manner, as if someone was orally telling the story. Phrases like, “Georgia, Jemima’s daughter, was high yaller likena her pa, Big

Rufus”, and “Jemima up and married Big Rufus anyway, and they run off to Tampa… cookin, cleanin and takin care a they chirrun” (Ringgold, 1983), are written in the typical vernacular often tied to African Americans. The sentences are ungrammatical and use incorrect words that only make sense when spoken aloud. Her message is that people don’t have to use correct grammar or be highly educated to be successful in life. Black women are one of the most underprivileged minorities in the United States, so some may not have the option of higher education available to them. By closely relating to her community’s language, Ringgold creates a pathos-ridden message to her African

American audience. Again, since the artist writes about a successful black woman who did not attend college, but worked hard to get to her status in life, she supports the idea that black women may have a disadvantage in society, but that doesn’t mean they cannot be successful. Jemima, pictured in an opulent dress with an extravagant necklace, hat, and feather, and a sly smile on her face, is the embodiment of this resilient black female figure.

Ringgold’s activist work for black and female improvement during the 1980s is still relevant today. She and her contemporaries laid the groundwork for black female rights through protests and artwork alike, but the struggle will not be over for years to come. The topic of women’s rights was hot during the 1980s; the Equal Rights

Amendment affirming gender equality in the United States was nearly added to the

Constitution in 1982, but narrowly missed ratification (Francis). Since Ringgold’s piece 8 was finished in 1983, her moment of addressing the issue of gender inequality was spot on. By creating a piece directly relating to the important issues at the time, Ringgold took a stance and became an spokeswoman through her art and her activism. Due to the rhetorical “kairos” out of which this work of art arose, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? has become a historically important piece in art history as well as in the history of women’s rights. In this way, Ringgold mirrors her character again; Ringgold made a name for herself through hard work and by fighting against racial inequalities, much like our no- nonsense character Jemima. In addition, Ringgold fought alongside black female activists, and on the quilt are portraits of well-dressed black figures encircling and supporting Jemima. Since these issues are still relevant 30 years later, both Ringgold and

Jemima are perpetually marked as trailblazers for the minority, and spokeswomen for the voiceless. In this way, Jemima, the quintessence of the powerful black female, has become larger-than-life, and certainly larger than any plastic syrup bottle. So, the question begs to be asked; Are you afraid of her now? 9

Works Cited

Doyle, Nancy. "Artist Profile: Faith Ringgold." Nancy Doyle Fine Art. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Oct 2013.

Francis, Roberta. "The History Behind the Equal Rights Amendment." The Equal Rights Amendment . National Council of Women's Organizations. Web. 6 Oct 2013.

Hale, Christy. "Faith Ringgold." Instructor. Jan/Feb 2004: n. page. Web. 8 Oct. 2013.

Ringgold, Faith. "Biography, Faith Ringgold." Scholastic. n.d. n. page. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.

Ringgold, Faith. Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?. 1983., acrylic paint, textile

Wallace, Michele. "Whose Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983) by Faith Ringgold." Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman Revisited. N.p., 29 Feb 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.