December 2007/January 2008 | Volume 65 | Number 4 Informative Assessment

What Student Writing Can Teach Us

Mark Overmeyer

"If you read carefully, a poem will teach you how to read it."

This comment came from Jake York, a poet and teacher who was facilitating a summer institute workshop offered by the Denver Writing Project. I immediately copied this statement into my writer's notebook. Jake had been helping us unravel the meaning behind a tricky poem. He kept encouraging us to stick with it and assured us we would be rewarded with greater understanding. Because my work as a district literacy coordinator means I lead teachers in carefully examining and assessing student writing, I began to wonder whether it is possible to read student writing in the same way Jake suggested we read poetry.

Can student writing "teach" us how to read it if we look carefully at what the writer has to say, where the writer shines in saying it, and what instruction would increase the writer's polish? And if so, can we use this technique of careful reading as a kind of formative assessment to guide instruction? And can the rubrics now so common in evaluating student writing help teachers read more deeply? Moving Beyond the Score

Teachers use rubrics, scoring guides that define expectations at various performance levels, to guide their reading of student work. When any group of teachers meets to assess student writing, their first step is often to examine the rubric. Rubrics are meant to make the scoring of writing less subjective, but although this is a laudable goal, I have seen teachers in many scoring sessions wrestle to reach agreement on a particular score.

In my school district, which is heavily involved in using rubrics to examine student work, teachers often spend many hours scoring and cross-scoring samples of writing, determining which pieces best reflect various performance levels. Some good comes from this: We have raised our expectations for student writing, and we are more transparent about what we expect. But when our thinking doesn't move beyond reaching a score in these meetings, we are not taking advantage of what the writing can teach us.

Last spring, I worked with a group of about 20 teachers from grades K–12 in my district. We were meeting to align our district's benchmarks document with actual student writing samples. During one particular session, we decided to discuss one piece in a large group to clarify our own thinking. We chose the following 4th grade piece:

My favorite place to play is my bedroom. My bedroom is painted extremely light pink. Also I have a peanut-colored carpet. It is full of meowing. It never stops! Most of the time I play by myself. My friend Megan comes over sometimes. When Megan is in my room we play Pokemon Stadium. Another thing we do is play with my multicolored cat. Her name is Maxie. We throw a lime green toy mouse for Maxie and she sprints after it. Megan and I also throw a ball for Maxie to get. We also play Conga sometimes. I play in my room at 3:30 pm with Megan. I like to play in my room because it is very fun and it is mine. I love to play in my room!

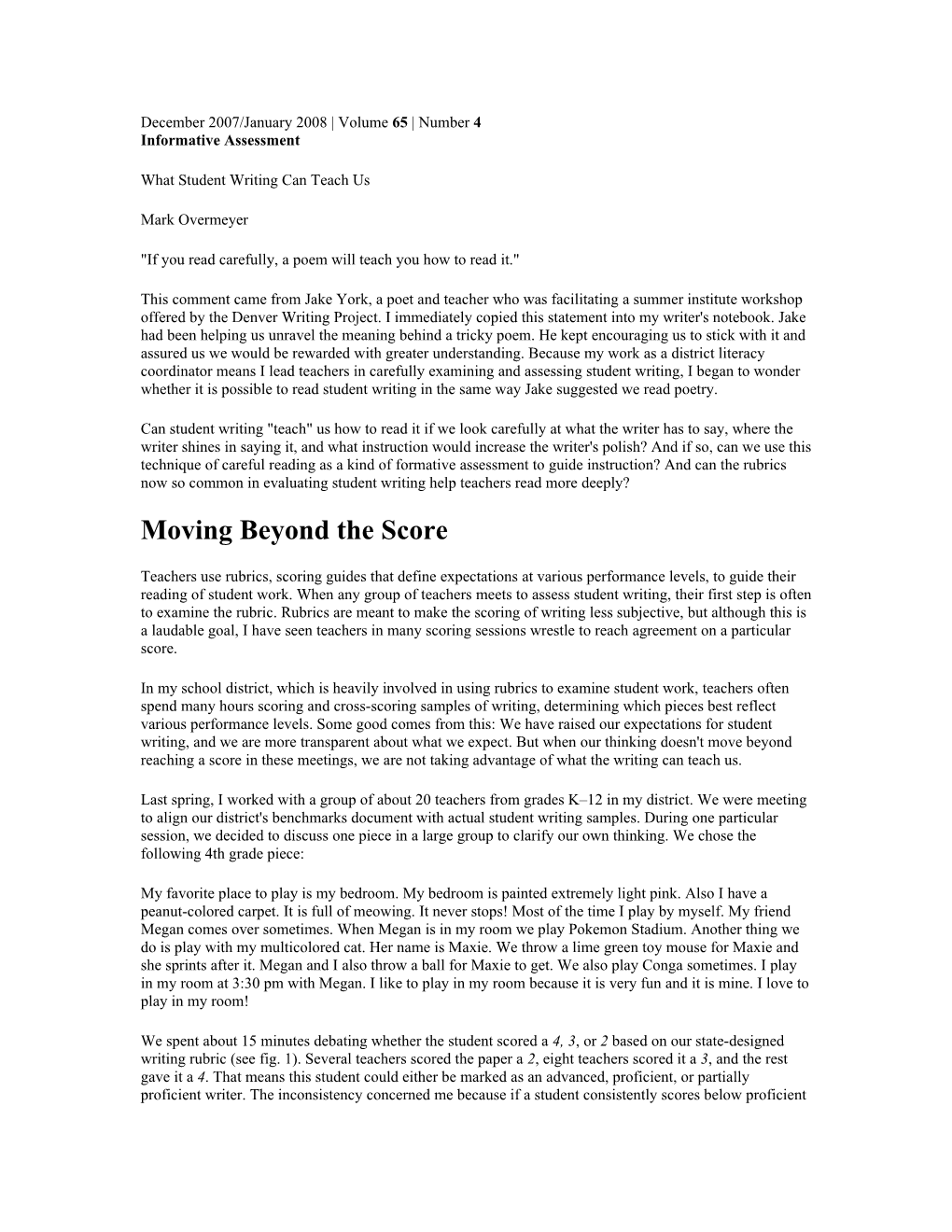

We spent about 15 minutes debating whether the student scored a 4, 3, or 2 based on our state-designed writing rubric (see fig. 1). Several teachers scored the paper a 2, eight teachers scored it a 3, and the rest gave it a 4. That means this student could either be marked as an advanced, proficient, or partially proficient writer. The inconsistency concerned me because if a student consistently scores below proficient on standardized assessments in my district, then the school must develop a learning plan, hold a parent conference, and discuss interventions for the student. So if we intend for rubrics to clarify, how did this group of teachers end up in a potentially high-stakes debate on this student? And why did we spend 15 minutes talking about a score without thinking about how this piece might inform our instruction for this writer? If rubrics are to be used successfully for formative assessment, we must look beyond the search for a score.

Figure 1. Holistic Writing Rubric for the Short Constructed-Response Task — Grades 4–10

Score Content and Organization Style and Fluency Level

Supporting details are relevant and The writer selects words provide important information about that are accurate, specific, the topic. and appropriate for the The writing has balance; the main idea specified purpose. stands out from the details. The writer may experiment The writer seems in control and with words and/or use develops the topic in a logical, figurative language and/or 4 organized way. imagery. The writer connects ideas to the The writer uses a variety of specified purpose. sentence structures. The writing is readable, neat, and nearly error-free.

The writer has defined but not The writer mostly selects thoroughly developed the topic, idea, words that are accurate, or story line. specific, and appropriate Some supporting details are relevant for the purpose of the but limited or overly general or less writing. important. The writer uses age- The writer makes general observations appropriate words that are without using specific details or does accurate but may lack not delineate the main idea from the precision. 3 details. The writer uses simple but The writer attempts to develop the accurate sentence topic in an organized way but may structures. falter in either logic or organization. Errors in language usage, The writer connects ideas with the spelling, and mechanics do specified topic implicitly rather than not impede explicitly. communication.

2 The writer has defined but not The writer sometimes thoroughly developed the topic, idea, selects words that are not or story line; response may be unclear accurate, specific, or or sketchy or may read like a appropriate for the purpose collection of thoughts from which no of the writing. central idea emerges. Writing may be choppy or Supporting details are minimal or repetitive. irrelevant or no distinction is made Portions of the writing are between main ideas and details. unreadable or messy; errors The writer does not develop the topic may impede in an organized way; response may be communication in some a list rather than a developed portions of the response. paragraph. Ideas are not connected to the specified purpose.

The writer has not defined the topic, Much of the writing is idea, or story line. unreadable or messy. Supporting details are absent. Word choice is inaccurate Organization is not evident; may be a or there are many brief list. repetitions. Ideas are fragmented and unconnected Vocabulary is age- with the specified purpose. inappropriate. 1 The writer uses simple, repetitive sentence structures or many sentence fragments. Errors severely impede communication.

The response is off-topic or The response is off-topic or unreadable. unreadable. 0

Courtesy of Unit of Assessment, Colorado Department of Education. This material also appeared in When Writing Workshop Isn't Working, by Mark Overmeyer, 2005, Portland, ME: Stenhouse. Used with permission.

Using Rubrics Formatively

Holistic rubrics that give only one score—which evaluators often use for state and national testing—are particularly difficult to use for informing instruction because the assessor cannot separate out individual qualities of the writing. Each piece can only receive one score. Trait-based rubrics lend themselves better to differentiated comments, but assessors still must give a single score for each trait. So even if a piece has strengths, readers can't highlight strengths fairly in the push to give the entire paper one mark. But teachers can, and should, adapt rubrics to serve the purposes of guiding our instruction as well as the purposes of testing. When the teacher group I lead in finding exemplars for our district finally moved the conversation away from scoring the 4th grader's paragraph, we engaged in discussion about what this writer did well and how she could improve. We all agreed that the student clearly stayed on the topic, provided sufficient supporting details, and showed some strong word choice. We soon began discussing instructional strategies, which is a crucial step in assessing student writing. Everyone agreed that although specificity and rich vocabulary were the writer's strong suit, she could benefit from thinking about how to organize details within a piece of writing. This experience helped us realize as a group that the goal of looking at student writing must be to develop strategies to help students write better. Signaling Strengths and Weaknesses

Because our group began focusing more on how to help teachers see our thinking about each piece of writing, we had to devise a format that would show teachers that deeper thinking and give them a model for using a rubric to inform instruction. Our goal was to provide a more helpful document than a tidy, completed rubric. We created a chart on writing strengths and weaknesses (shown in fig. 2). This format draws from the state-created rubric (fig. 1) but shows how a teacher can annotate student work in such a way as to discover what to teach a student next—in other words, to hear what the writing has to teach.

Figure 2. Strengths and Weaknesses Found in a 4th Grader’s Essay

Meets or Exceeds These Does Not Meet These Suggested Next Instructional Benchmarks Benchmarks Strategies

Supporting details The writer seems in This student may benefit are relevant. control and from creating a bulleted The writer connects develops the topic list or a graphic ideas to the in an organized organizer prior to specified purpose. way. writing. The writer selects The teacher can ask the words that are student to read through accurate and the piece aloud to clarify specific. any confusing details. The writer uses a variety of sentence structures. The writing is nearly error-free.

Sample chart annotating a piece of writing’s strengths and weaknesses in terms of benchmarks on a standardized rubric. Benchmarks are drawn from the Colorado Department of Education’s rubric for student writing.

Overmeyer, M. (2007/2008). What Student Writing Can Teach Us. Educational Leadership, 65(4) [Online]. Figure 2 shows how we pinpointed strengths and weaknesses for the 4th grader's piece on her room. It indicates which benchmarks from the rubric this writer meets (such as including relevant details), which benchmarks need more work (such as organization), and a few suggested next steps (such as creating a bulleted list). Comments on a chart like this can be directly aligned to the rubric, as shown here, or be based on teacher discussion. Either way, the goal is to read more deeply and go for teaching points.

We explained to administrators and curriculum leaders in language arts departments throughout the district our thinking about how student writing samples can be used to inform instruction and made this annotated format accessible on our district Web site. Teachers at all grade levels have used the format to work with student writing.

Like a well-written poem, each piece of student writing can teach us how to read it—and how to read the author's needs. Every piece of writing we collect from students can become part of formative assessment.

Mark Overmeyer is Literacy Coordinator at Cherry Creek School District in Denver, Colorado, and the author of When Writing Workshop Isn't Working (Stenhouse, 2005); [email protected].

Copyright © 2007 by Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development