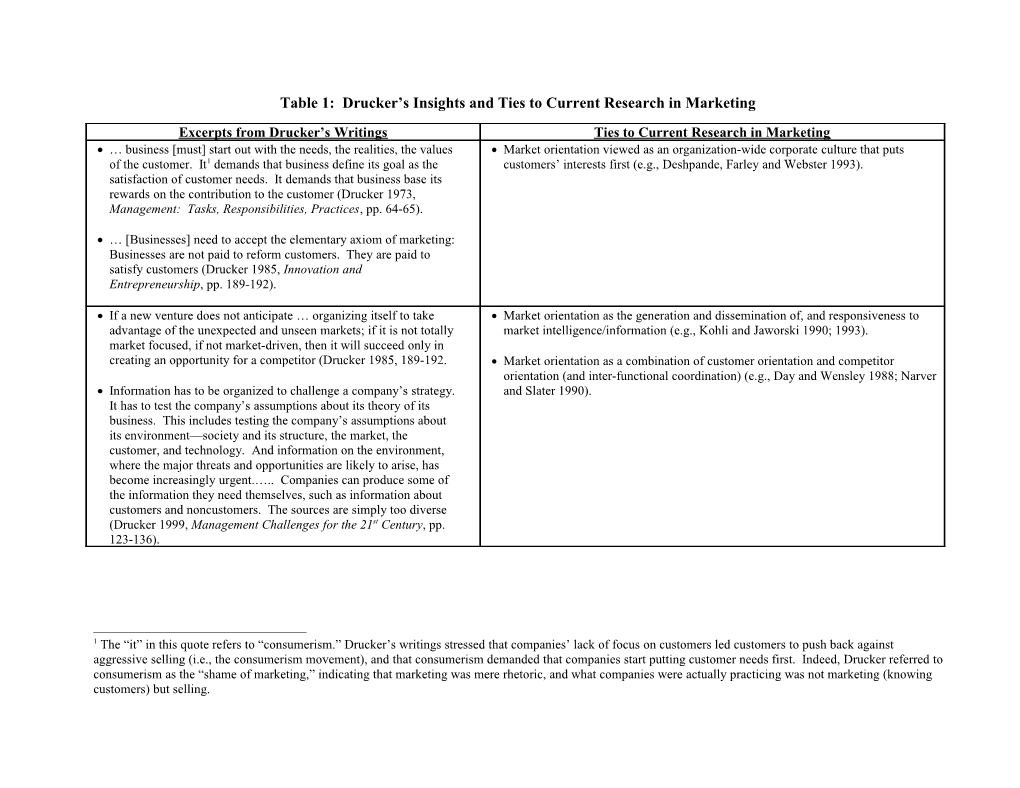

Table 1: Drucker’s Insights and Ties to Current Research in Marketing

Excerpts from Drucker’s Writings Ties to Current Research in Marketing … business [must] start out with the needs, the realities, the values Market orientation viewed as an organization-wide corporate culture that puts of the customer. It1 demands that business define its goal as the customers’ interests first (e.g., Deshpande, Farley and Webster 1993). satisfaction of customer needs. It demands that business base its rewards on the contribution to the customer (Drucker 1973, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices, pp. 64-65).

… [Businesses] need to accept the elementary axiom of marketing: Businesses are not paid to reform customers. They are paid to satisfy customers (Drucker 1985, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, pp. 189-192).

If a new venture does not anticipate … organizing itself to take Market orientation as the generation and dissemination of, and responsiveness to advantage of the unexpected and unseen markets; if it is not totally market intelligence/information (e.g., Kohli and Jaworski 1990; 1993). market focused, if not market-driven, then it will succeed only in creating an opportunity for a competitor (Drucker 1985, 189-192. Market orientation as a combination of customer orientation and competitor orientation (and inter-functional coordination) (e.g., Day and Wensley 1988; Narver Information has to be organized to challenge a company’s strategy. and Slater 1990). It has to test the company’s assumptions about its theory of its business. This includes testing the company’s assumptions about its environment—society and its structure, the market, the customer, and technology. And information on the environment, where the major threats and opportunities are likely to arise, has become increasingly urgent.….. Companies can produce some of the information they need themselves, such as information about customers and noncustomers. The sources are simply too diverse (Drucker 1999, Management Challenges for the 21st Century, pp. 123-136).

1 The “it” in this quote refers to “consumerism.” Drucker’s writings stressed that companies’ lack of focus on customers led customers to push back against aggressive selling (i.e., the consumerism movement), and that consumerism demanded that companies start putting customer needs first. Indeed, Drucker referred to consumerism as the “shame of marketing,” indicating that marketing was mere rhetoric, and what companies were actually practicing was not marketing (knowing customers) but selling. Table 1 (Continued) Excerpts from Drucker’s Writings Ties to Current Research in Marketing Market domination tends to lull the leader to sleep …. Market Neglecting new innovations because of investments –both marketing and domination produces tremendous internal resistance against any manufacturing investments—in a current product offering is consistent with the innovation and thus makes adaptation to change dangerously notion of the “innovator’s dilemma” (Christensen 1997) and the subsequent difficult (Drucker 1973, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, dialogue spawned with Christensen’s theory of disruption (cf. Daneels 2006). Practices, pp. 105-107). Organizational competence, as embedded in routines, procedures, and Success always obsoletes the very behavior that achieved it. It knowledge of established companies, is likely a central reason for the failure of always creates new realities. It always creates, above all, its own established firms to compete effectively with disruptive innovation (Henderson and different problems. It is not easy for the management of a 2006). successful company to ask, “What is our business?” Everybody in the company thinks that the answer is so obvious as not to deserve discussion. It is never popular to argue with success, never popular to rock the boat. But the management that does not ask “What is our business?” when the company is successful is, in effect, smug, lazy, and arrogant. It will not be long before success will turn into failure…Above all: when management attains the company’s objectives, it should always ask seriously, ‘What is our business?’ This requires self-discipline and responsibility. The alternative is decline (Drucker 1973, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practice, pp. 88, 106).

A large organization is effective through its mass rather than In contrast to an “incumbent’s curse,” more radical innovations have been through its agility. Mass enables the organization to put to work a introduced by larger, established firms than by smaller firms and new entrants. great many more kinds of knowledge and skill than could possibly As radical innovations and the technology necessary to generate them become be combined in any one person or small group (Drucker 1968, The more complex, larger firms with greater resources for both R&D and marketing, Age of Discontinuity, pp. 192-193). have an edge in developing such innovations (Chandy and Tellis 2000).

Innovating organizations spend neither time nor resources on Chandy and Tellis (1998) operationalized this notion of creative destruction in defending yesterday. Systematic abandonment of yesterday alone their empirical study of the factors that facilitate an organization’s development can free the resources, and especially the scarcest resource of them of radical technological innovations. More specifically, they found that all, capable people, for work on the new. Your being the one who managers in firms who market the dominant technology in the industry are more makes your product, process, or service obsolete is the only way to “willing to cannibalize” their legacy products when they have a focus on prevent your competitor from doing so (Drucker 1992, Managing “markets of the future” rather than on current markets and current customers. for the Future, pp. 281-282). Table 1 (Continued) It is always with noncustomers that basic changes begin and Consistent with the idea of the “innovator’s solution” (Christensen and Raynor become significant. At least half of the important new 2003), companies should not be overly wedded to an existing customer base. technologies that have transformed an industry in the past fifty years came from outside the industry itself (Drucker 1999, The difficulty of established companies to introduce disruptive innovations is Management Challenges for the 21st Century, pp. 121-123). not simply due to failures in product development; the difficulty is also due to excessive reliance on a certain class of customers (see also Danneels 2002, 2004): “focusing on their current customers, managers literally do not see other opportunities” (Henderson, 2006, p. 7).

Businesses, like judo fighters, tend to become set in their A 1999 Harvard Business Review article (and a subsequent book on the topic), behaviors. And then Entrepreneurial Judo turns what the market discussed in detail how companies can implement judo tactics (Yoffie and leaders consider their strengths into the very weaknesses that Cusumano 1999; Yoffie and Kwak 2001). defeat them. For example, the Japanese became the leaders in one American market after the other …The Americans saw high profitability as their greatest strength. And thus they focused on the high end of the market and left the mass market undersupplied and under-serviced. The Japanese moved in with low-cost products with minimum features. The Americans didn’t even try to fight them. But when the Japanese had taken over the mass market, they had the cash flow to move in on the high-end market, too. And they soon came to dominate both the mass market and the high-end market (Drucker 1985, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, pp. 225-227).

Under the other entrepreneurial strategies, the innovator has to Disruption can occur not only in the development of radical new technologies, come up with an innovative product or service; here the strategy but also in the creation of new business models that disrupted the existing “rules itself is the innovation. The innovative strategy converts an of the game” for a particular industry (Christensen 1997; Hamel 1997; Hamel existing product or service into something new by changing its and Prahalad 1996). utility, its value, and its economic characteristics. There is new economic value and new customers, but no new product or service. … This changes the characteristics of the industry (Drucker 1985, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, pp. 2, 43, 247). Table 1 (Continued) Innovative efforts, especially those aimed at developing new “Nurseries” to nurture new innovations, unfettered by the “adults,” are often businesses, products, or services, should normally report directly to referred to as skunkworks, new product innovation teams that work outside the the ‘executive in charge of innovation.’ They should never report normal operating rules and procedures of the company in order that they avoid to line managers charged with responsibility for ongoing being encumbered by the old way of doing business. Leifer, et al. (2000) found operations. Unfortunately, this is a common error. The new that in most established firms, radical innovation efforts need to be nurtured product is an infant and will remain one for the foreseeable future outside the mainstream protocols guiding innovation (i.e., the company’s new and infants belong in the nursery. The ‘adults,’ that is, the product development processes and procedures); successful radical innovation executives in charge of existing businesses or products, will have efforts needed to be protected from the methods of performance evaluation and neither time nor understanding for the infant project. The best- accountability (such as financial/accounting metrics) traditionally employed by known practitioners of this approach … set up the new venture as a the firms’ managers, especially early in the innovation’s development. separate business from the beginning and put a project manager in charge (Drucker 1985, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, pp. 162- 163).

… Modern organization must be capable of initiating change, that This is commonly known today as the knowledge-based view of the firm (Grant is, innovation. It must be able to move scarce and expensive 1996; Kogut and Zander 1992; Nonaka 1994), and the related stream of resources of knowledge from areas of low productivity and literature on organizational learning. Innovative organizations have a learning nonresults to opportunities for achievement and contribution. This, orientation (Darroch and McNaughton 2003; Slater and Narver 1995), including however, requires the ability to stop doing what wastes resources the capability to unlearn (Akgun, Lynn and Bryne 2006). (Drucker 1968, The Age of Discontinuity, pp. 192-193).

An organization must be organized for constant change. It will no longer be possible to consider entrepreneurial innovation as lying outside of management or even as peripheral to management. Entrepreneurial innovation will have to become the very heart and core of management. The organization’s function is entrepreneurial, to put knowledge to work – on tools, products, and processes; on the design of work; on knowledge itself (Drucker 1954, The Practice of Management, p. 70). [Citing IBM’s eventual success in the PC market, relative to Regarding the value of a fast-follower strategy, Min, Kalwani, and Robinson Apple, as an example of a “fast follower” strategy], the innovator (2006) showed that for radical innovations, fast followers outperform market doesn’t create a major new product or service. Instead, it takes pioneers (see also Slater, Hult, and Olson 2007). something just created by somebody else and improves upon it. This is imitation. But it is creative imitation because the innovator reworks the new product or service to better satisfy customers’ wants and needs. Once the innovator succeeds in creating what customers want, it can achieve leadership and take control of the market (Drucker 1985, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, pp. 220 -221).