Chapter 14: The Digestive System Lecture Notes taken from: Marieb,E.N. 2009. Essentials of Human Anatomy and Physiology. PBC

The digestive system is basically a tube with 2 openings (mouth and anus) and a set of accessory organs that empty secretions into the tube to promote digestion (i.e. the breakdown of food into nutrients). The hollow center of the ‘tube’ is called the lumen; food and liquid inside the lumen are actually outside the body until they are absorbed by passing through body membranes and into the blood.

There are 4 different functional operations of the digestive system: Ingestion – taking food into the body. Digestion – food must be broken down into nutrient molecules small enough to be absorbed. Absorption – nutrients and fluids must be passed across the lumen wall and into the blood. Defecation – undigested/unabsorbed residues must be eliminated.

General anatomy along the ‘tube’ includes the mouth (oral cavity), pharynx (throat), esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anus – these structures make up the alimentary canal (a.k.a. the gastrointestinal tract; a.k.a. the GI tract). Accessory organs (salivary glands, pancreas, and liver with gallbladder) produce necessary digestive enzymes and other materials, but are located outside of the tube.

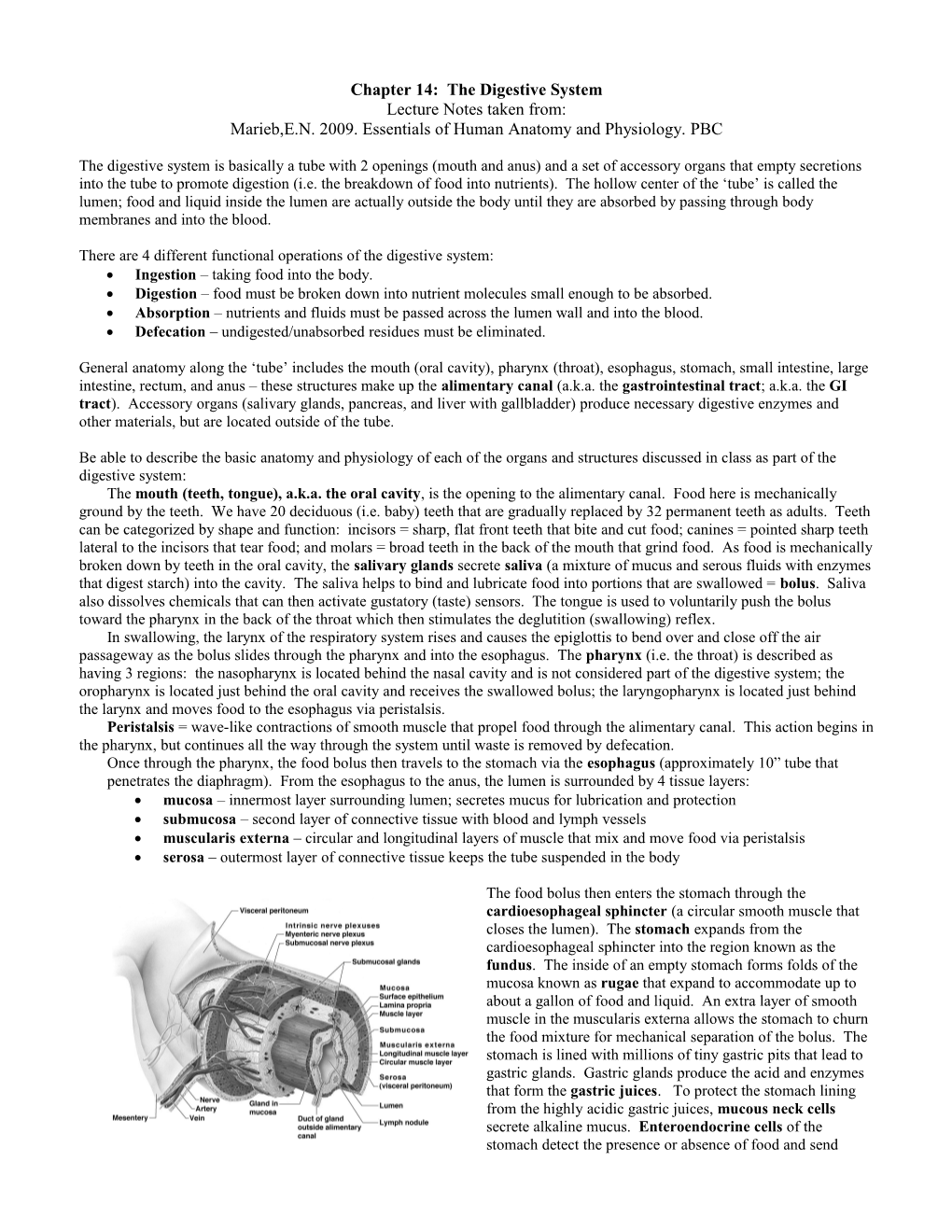

Be able to describe the basic anatomy and physiology of each of the organs and structures discussed in class as part of the digestive system: The mouth (teeth, tongue), a.k.a. the oral cavity, is the opening to the alimentary canal. Food here is mechanically ground by the teeth. We have 20 deciduous (i.e. baby) teeth that are gradually replaced by 32 permanent teeth as adults. Teeth can be categorized by shape and function: incisors = sharp, flat front teeth that bite and cut food; canines = pointed sharp teeth lateral to the incisors that tear food; and molars = broad teeth in the back of the mouth that grind food. As food is mechanically broken down by teeth in the oral cavity, the salivary glands secrete saliva (a mixture of mucus and serous fluids with enzymes that digest starch) into the cavity. The saliva helps to bind and lubricate food into portions that are swallowed = bolus. Saliva also dissolves chemicals that can then activate gustatory (taste) sensors. The tongue is used to voluntarily push the bolus toward the pharynx in the back of the throat which then stimulates the deglutition (swallowing) reflex. In swallowing, the larynx of the respiratory system rises and causes the epiglottis to bend over and close off the air passageway as the bolus slides through the pharynx and into the esophagus. The pharynx (i.e. the throat) is described as having 3 regions: the nasopharynx is located behind the nasal cavity and is not considered part of the digestive system; the oropharynx is located just behind the oral cavity and receives the swallowed bolus; the laryngopharynx is located just behind the larynx and moves food to the esophagus via peristalsis. Peristalsis = wave-like contractions of smooth muscle that propel food through the alimentary canal. This action begins in the pharynx, but continues all the way through the system until waste is removed by defecation. Once through the pharynx, the food bolus then travels to the stomach via the esophagus (approximately 10” tube that penetrates the diaphragm). From the esophagus to the anus, the lumen is surrounded by 4 tissue layers: mucosa – innermost layer surrounding lumen; secretes mucus for lubrication and protection submucosa – second layer of connective tissue with blood and lymph vessels muscularis externa – circular and longitudinal layers of muscle that mix and move food via peristalsis serosa – outermost layer of connective tissue keeps the tube suspended in the body

The food bolus then enters the stomach through the cardioesophageal sphincter (a circular smooth muscle that closes the lumen). The stomach expands from the cardioesophageal sphincter into the region known as the fundus. The inside of an empty stomach forms folds of the mucosa known as rugae that expand to accommodate up to about a gallon of food and liquid. An extra layer of smooth muscle in the muscularis externa allows the stomach to churn the food mixture for mechanical separation of the bolus. The stomach is lined with millions of tiny gastric pits that lead to gastric glands. Gastric glands produce the acid and enzymes that form the gastric juices. To protect the stomach lining from the highly acidic gastric juices, mucous neck cells secrete alkaline mucus. Enteroendocrine cells of the stomach detect the presence or absence of food and send hormonal signals that regulate stomach activity. In the stomach: Gastric juices (acid and enzymes) begin breakdown of proteins as food is mixed and chyme (highly acidic mixture of food and gastric juices) is produced. Acid kills most microbes and helps break down proteins. The pyloric sphincter moderates the passage of the resulting chyme into the small intestine. Only small amounts of chyme are released into the small intestine; 4 to 6 hours required to empty a full stomach. Though few if any nutrients are absorbed in the stomach, both alcohol and aspirin are absorbed through the stomach lining.

The small intestine is divided into 3 major regions: duodenum = first section joining the stomach; jejunum = middle section; and the ileum = last section that connects to the large intestine. In the small intestine: Bicarbonate from pancreas neutralizes the acidic chyme and enzymes from the pancreas and bile (required for fat digestion) from the gallbladder continue the breakdown of food. The digestive enzymes from the pancreas are capable of breaking down all of the important biological molecules (fats, carbs, proteins, and nucleic acids) into there basic components. Most digestion and absorption takes place in the small intestine: 20 feet long and enormous surface area created by circular folds, villi (finger-like projections of the mucosa), and microvilli (tiny outward folds of the cell membranes of the epithelial cells) allow for efficient absorption of nutrients into the blood. Bile is made by the liver and is composed of salts and lipids that act like soap to emulsify (break down large fat droplets into smaller ones) fats so that enzymes can interact to break the fat molecules down. Cholesterol (a normal component of bile) can crystallize under certain conditions to form painful gallstones that can block the release of bile.

In the large intestine: Some nutrients are absorbed, lots of water is absorbed, and waste products are eliminated. Near the beginning of the large intestine is a fingerlike pocket known as the appendix. Little is known about the function of the appendix, but if feces back up into the appendix it can easily become inflamed = appendicitis. Two sphincters control the opening of the anus, an internal involuntary sphincter relaxes when feces distend the rectum and stimulates the urge to defecate; final release is under the voluntary control of the external anal sphincter.

A final note on the liver: The liver is the largest gland of the body responsible for bile production, but it is also responsible for managing the nutrients absorbed by the digestive system. Unlike most capillary beds, those surrounding the small intestine do not drain directly back to the heart. Instead, nutrient rich blood is delivered to the liver via the hepatic portal vein where the nutrients are stored and managed by the liver.

Control of the digestion process is carried out by both the nervous system (electrical communication) and the endocrine system (molecule/hormonal communication). Respond to amount of food and the chemical make-up of food. Some examples: Nerves detect stretching stomach and send “full” message to brain. Proteins in stomach are detected by stomach cells that send hormonal signal to release acid. Once empty, very high acidity of stomach triggers release of another hormone that signals the shutdown of acid production.