Chia-Ying Liao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

25 WNBA Facts

25 WNBA Facts Copyright (c) 2021 Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast 25 WNBA Facts In celebration of the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) 25th Season, Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast has developed 25 WNBA Facts for educational purposes. WNBA began its first season on June 21, 1997. 1 The first eight WNBA franchises were located in 2 cities with NBA teams. Currently, there are 12 WNBA teams: six in the eastern conference and 3 six in the western Sheryl Swoopes was the conference. first player signed to the 4 WNBA. Copyright (c) 2021 Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast 25 WNBA Facts The eight teams with the best regular season record qualify for the 5 postseason. Houston Comets (defunct) won the first four WNBA 6 titles: (1997, 1998, 1999, 2000). The 3-point line is 22 feet, 1.75 inches. 7 Cynthia Cooper is the only player in WNBA 8 history to win back-to-back WNBA MVP awards. Copyright (c) 2021 Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast 25 WNBA Facts The Houston Comets (defunct), the Minnesota Lynx, and the Seattle 9 Storm are tied with the most championship wins In its inaugural season, (4) in league history. WNBA attendance 10 exceeded one million fans. The tallest player is Margo Dydek (deceased). She was 7 feet, 2 inches. 11 Sue Bird became the first player in WNBA history to 12 win a championship in three different decades (2004, 2010, 2018, 2020). Copyright (c) 2021 Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast 25 WNBA Facts WNBA's regulation ball is 28.5 inches in circumference and one 13 inch smaller than the NBA’s regulation ball. -

Alp(LK)26 3 7 M.Mažvydo Biblioteka • ------SECOND CLASS USPS 157-580 the LITHUANIAN NATIONAL NEVVSPAPER 19807 CHEROKEE AVENUE CLEVELAND, OHIO 44119 VOL

,-zo-uvos , Alp(LK)26 3 7 M.Mažvydo biblioteka • ----------------------------------- SECOND CLASS USPS 157-580 THE LITHUANIAN NATIONAL NEVVSPAPER 19807 CHEROKEE AVENUE CLEVELAND, OHIO 44119 VOL. XCV 2010 DECEMBER - GRUODŽIO 7, NR.24. , DEVYNIASDEŠIMT PENKTIEJI METAI _____________________ LIETUVIŲ TAUTINĖS MINTIES LAIKRAŠTIS MĖNAIČIUOSE - LIETUVOS LAISVĖS KOVOS SĄJŪDŽIO MEMORIALAS Lapkričio 22 d. Miknių- vardai. džio Tarybos posėdyje priim Pėtrėčių sodyboje Mėnaičių Į bunkerio vidų patekti ta deklaracija, kurią pasirašė kaime, Radviliškio rajone, nebus galima, jį lankyto aštuoni posėdžio dalyviai. iškilmingai atidaryta Lietuvos jai galės apžiūrėti iš vir Nė vienas iš aštuonių šią laisvės kovos sąjūdžio šaus, įėję į atstatytą klėtį. istorinę deklaraciją pasira Tarybos 1949 m. vasario 16 Bunkerio viršus uždengtas šiusių signatarų neišdavė d. Nepriklausomybės deklara stiklu. Ekspozicijoje - restau juos saugojusių ir globoju cijos paskelbimo memorialas. ruoti partizanų daiktai, eks sių žmonių ir savo idealų. Memorialą, kurį sudaro ponatai iš Šiaulių „Aušros“ Deja, nė vienas legendinės atstatytas Lietuvos partizanų muziejaus ir Genocido aukų partizanų Deklaracijos si vyriausiosios vadavietės bun muziejaus fondų. gnataras laisvės nesulaukė. keris, virš jo esanti klėtis ir Istorija mena, kad Lietuva Nežinoma, kur ilsisi jų palai šalia bunkerio pastatytas pa ginklu priešintis sovietinei kai, todėl tikimasi, kad tin minklas, pašventino Lietuvos okupacijai pradėjo 1944 m. kamai sutvarkyta ši Lietuvai kariuomenės ordinaras vys ir ši kova tęsėsi iki 1953 m., svarbi istorinė vieta taps ne kupas Gintaras Grušas. kai buvo sunaikintos orga tik 1949 m. vasario 16-osios Memorialo atidarymo iš nizuotos Lietuvos partizanų deklaraciją pasirašiusių par kilmėse dalyvavo prezidentė pajėgos. tizanų atminimo ženklu, bet Dalia Grybauskaitė, kraš 1949 m. vasario 2-22 die ir amžinos pagarbos visų to apsaugos ministrė Rasa nomis Mėnaičių kaime buvo Lietuvos partizanų laisvės Juknevičienė, kariuomenės sušauktas visos Lietuvos siekiams simboliu. -

2020-21 Middle Tennessee Women's Basketball

2020-21 MIDDLE TENNESSEE WOMEN’S BASKETBALL Tony Stinnett • Associate Athletic Communciations Director • 1500 Greenland Drive, Murfreesboro, TN 37132 • O: (615) 898-5270 • C: (615) 631-9521 • [email protected] 2020-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS GAME 22: MIDDLE TENNESSEE VS. LA TECH/MARSHALL Thursday, March 11 , 2021 // 2:00 PM // Frisco, Texas OVERALL: 14-7 C-USA: 12-4 GAME INFORMATION THE TREND HOME: 8-5 AWAY: 6-2 NEUTRAL: 0-0 Venue: Ford Center at The Star (12,000) Location: Frisco, Texas NOVEMBER Tip-Off Time: 2:00 PM 25 No. 5 Louisville Cancelled Radio: WGNS 100.5 FM, 101.9 FM; 1450-AM Talent: Dick Palmer (pxp) 29 Vanderbilt Cancelled Television: Stadium Talent: Chris Vosters (pxp) DECEMBER John Giannini (analyst) 6 Belmont L, 64-70 Live Stats: GoBlueRaiders.com ANASTASIA HAYES is the Conference USA Player of the 9 Tulane L, 78-81 Twitter Updates: @MT_WBB Year. 13 at TCU L, 77-83 THE BREAKDOWN 17 Troy W, 92-76 20 Lipscomb W, 84-64 JANUARY 1 Florida Atlantic* W, 84-64 2 Florida Atlantic* W, 66-64 8 at FIU* W, 69-65 9 at FIU* W, 99-89 LADY RAIDERS (14-7) C-USA CHAMPIONSHIP 15 Southern Miss* W, 78-58 Location: Murfreesboro, Tenn. Location: Frisco, Texas 16 Southern Miss* L, 61-69 Enrollment: 21,720 Venue: Ford Center at The Star 22 at WKU* (ESPN+) W, 75-65 President: Dr. Sidney A. McPhee C-USA Championship Record: 10-4 Director of Athletics: Chris Massaro All-Time Conf. Tourn. Record: 61-23 23 at WKU* (ESPN+) W, 77-60 SWA: Diane Turnham Tourn. -

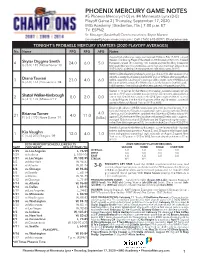

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) Vs

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) vs. #4 Minnesota Lynx (0-0) Playoff Game 2 | Thursday, September 17, 2020 IMG Academy | Bradenton, Fla. | 7:00 p.m. ET TV: ESPN2 Sr. Manager, Basketball Communications: Bryce Marsee [email protected] | Cell: (765) 618-0897 | @brycemarsee TONIGHT'S PROBABLE MERCURY STARTERS (2020 PLAYOFF AVERAGES) No. Name PPG RPG APG Notes Aquired by the Mercury in a sign-and-trade with Dallas on Feb. 12, 2020...named Western Conference Player of the Week on 9/8 for week of 8/31-9/6...finished 4 Skylar Diggins-Smith 24.0 6.0 5.0 the season ranked 7th in scoring, 10th in assists and tied for 4th in three-point G | 5-9 | 145 | Notre Dame '13 field goals (46)...scored a postseason career-high and team-high 24 points on 9/15 vs. WAS...picked up her first playoffs win over Washington on 9/15 WNBA's all-time leader in postseason scoring and ranks 3rd in all-time assists in the playoffs...6 assists shy of passing Sue Bird for 2nd on WNBA's all-time playoffs as- 3 Diana Taurasi 23.0 4.0 6.0 sists list...ranked 5th in the league in scoring and 8th in assists...led the WNBA in 3-pt G | 6-0 | 163 | Connecticut '04 field goals (61) this season, the 11th time she's led the league in 3-pt field goals... holds a perfect 7-0 record in single elimination games in the playoffs since 2016 Started in 10 games for the Mercury this season..scored a career-high 24 points on 9/11 against Seattle in a career-high 35 mimutes...also posted a 2 Shatori Walker-Kimbrough 8.0 2.0 0.0 career-high 5 steals this season in the 8/14 game against Atlanta...scored G | 6-1 | 170 | Missouri '19 in double figures 5 of the final 8 games of the regular season...scored 8 points in Mercury's Round 1 win on 9/15 vs. -

USA Vs. Oregon State

USA WOMEN’S NATIONAL TEAM • 2019 FALL TOUR USA vs. Oregon State NOV. 3, 2019 | GILL COLISEUM | 7 PM PST | PAC-12 NETWORKS PROBABLE STARTERS 2019-20 SCHEDULE/RESULTS (7-0) NO NAME PPG RPG APG CAPS 2019 FIBA AMERICUP (6-0) 5 Seimone Augustus 10.8 1.8 2.6 105 6 Sue Bird 10.1 1.7 7.1 140 9/22 USA 110, Paraguay 31 13 Sylvia Fowles 13.6 8.9 1.5 73 9/24 USA 88, Colombia 46 16 Nneka Ogwumike 16.1 8.8 1.8 48 9/25 USA 100, Argentina 50 12 Diana Taurasi 20.7 3.5 5.3 132 9/26 USA 89, Brazil 73 9/28 USA 78, Puerto Rico 54 9/29 USA 67, Canada 46 RESERVES 2019 FALL TOUR (1-0) NO NAME PPG RPG APG CAPS 23 Layshia Clarendon 4.8 1.8 2.2 21 11/2 USA 95, No. 3 Stanford 80 Pac-12 Networks 24 Napheesa Collier 13.1 6.6 2.6 40* 11/4 Oregon State (7/6)7 pm Pac-12 Networks 17 Skylar Diggins-Smith 17.9 3.3 6.2 38* 11/7 Texas A&M (6/7) 7 pm TBA 35 Allisha Gray 10.6 4.1 2.3 3 11/9 Oregon (1/1) 4 pm Pac-12 Networks 18 Chelsea Gray 14.5 3.8 5.9 0 2019 FIBA AMERICAS PRE-OLYMPIC 9 A’ja Wilson 16.5 6.4 1.8 39 QUALIFYING TOURNAMENT NOTES: 11/14 USA vs. Brazil Bahía Blanca, ARG • Stats listed for most athletes are from the 2019 WNBA 11/16 USA vs. -

North Carolina State University's Student Newspaper Since 1920

Weath‘ér Time to break out the electric blankets, muffs and long underwear 'cause it‘s 30mg to be a Techniciana bit on the nippy side tonight, baby! Today's highs shOuId be In the low 505, wuth tonight's lows North Carolina State University’s Student Newspaper Since 1920 plummeting to the 905 Volume LXVII. Number 40 Monday. December 2. 1985 Raleigh. North Carolina Phone 737-241 1/2412 Improvements cited for fee increases John Price have resources to meet." Haywood Dorsch said publications fees Staff Writer said. haven't increased since 1980 and that Housing costs will increase for he anticipated another fee increase Various university departments students in fraternity houses if an won't be needed for another four explained before the Student Fee increase proposed by the Fraternity years. Review Committee last week why Court Renters Board is approved. A representative from University they are requesting increased stu~ The board requested an increase of Dining said a $50 increase in the cost dent fees. $2.000 per house for next year. A of meal plans is necessary to pay for If approved by the university. the board member said the increase is salary increases and rising food proposed increases would increase necessary to repair many of the prices. tuition for the 198687 year by $21 houses. The official said the increases were and would increase the yearly cost of The board originally planned to unavoidable because salaries were a dorm room from $56 to 890. ask for a $4.000 increase but decided increased by the state Legislature depending on the residence hall. -

WOMEN in SPORTS Live Broadcast Event Wednesday, October 14, 2020, 8 PM ET

Annual Salute to WOMEN IN SPORTS Live Broadcast Event Wednesday, October 14, 2020, 8 PM ET A FUNDRAISING BENEFIT FOR Women’s Sports Foundation Sports Women’s Contents Greetings from the Women’s Sports Foundation Leadership ...................................................................................................................... 2 Special Thanks to Yahoo Sports ....................................................................................................................................................................4 Our Partners ....................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Benefactors ......................................................................................................................................................................................................6 Our Founder .....................................................................................................................................................................................................8 Broadcast Host ................................................................................................................................................................................................9 Red Carpet Hosts ............................................................................................................................................................................................10 -

Women's Basketball Women's Basketball

2014-15 USC WOMEN’S BASKETBALL 2014-15 USC WOMEN’S BASKETBALL 2014-15 USC WOMEN’S BASKETBALL #1 Jordan Adams #5 McKenzie Calvert #10 Courtney Jaco #13 Kaneisha Horn #21 Alexyz Vaioletama #23 Brianna Barrett Cynthia Cooper-Dyke Beth Burns #24 Drew Edelman #25 Alexis Lloyd #23 Brianna Barrett #32 Kiki Alofaituli #35 Kristen Simon #43 Amy Okonkwo Beth Burns Jualeah Woods Taja Edwards 2014-15 USC WOMEN’S BASKETBALL Numerical No. Name Pos. Ht. Yr. Exp. Hometown Previous School 1 Jordan Adams G 6-1 So.* 2V Irvine, Calif. Mater Dei HS 5 McKenzie Calvert G 5-9 Fr. HS Schertz, Texas Byron P. Steele HS 10 Courtney Jaco G 5-8 So. 1V Compton, Calif. Windward School 13 Kaneisha Horn F 6-1 Sr. 1V Birmingham, Ala. Ramsay HS/Alabama 21 Alexyz Vaioletama F 6-1 Sr. 3V Fountain Valley, Calif. Mater Dei HS 23 Brianna Barrett G 5-7 Jr. 2V Winnetka, Calif. Oaks Christian HS 24 Drew Edelman F 6-4 So. 1V Sunnyvale, Calif. Menlo School 25 Alexis Lloyd G 5-9 So. RS Chicago, Ill. Whitney Young HS/Virginia Tech 32 Kiki Alofaituli G 6-1 Sr. 2V Tustin, Calif. Mater Dei HS 35 Kristen Simon F 6-1 Fr. HS Gardena, Calif. Windward School 43 Amy Okonkwo F 6-2 Fr. HS Fontana, Calif. Etiwanda HS Alphabetical No. Name Pos. Ht. Yr. Exp. Hometown Previous School 1 Jordan Adams G 6-1 So.* 2V Irvine, Calif. Mater Dei HS 32 Kiki Alofaituli G 6-1 Sr. 2V Tustin, Calif. Mater Dei HS 23 Brianna Barrett G 5-7 Jr. -

Reps. Cheeks, Pastor, Voorhees, Bieda, Brandenburg, Condino

Reps. Cheeks, Pastor, Voorhees, Bieda, Brandenburg, Condino, Dennis, Farrah, Richardville, Sak, Spade, Waters, Emmons, Hager, Hopgood, Kolb, Kooiman, Law, Murphy, O'Neil, Stahl, Stallworth, Tobocman, Wojno, Adamini, Anderson, Brown, Caswell, Caul, Daniels, DeRossett, Elkins, Farhat, Gieleghem, Gillard, Jamnick, Julian, Lipsey, Nitz, Paletko, Reeves, Rivet, Sheltrown, Shulman, Smith, Woodward and Zelenko offered the following resolution: House Resolution No. 121. A resolution honoring the Detroit Shock Basketball Team and Head Coach Bill Laimbeer upon winning their first Women’s National Basketball Association Championship. Whereas, With no starting players older than 28 and no player older than 29, the Detroit Shock are now among the WNBA elite as they defeated their rivals the New York Liberty and the Charlotte Sting to win the Eastern Conference Championship. The Shock became the first Eastern Conference team to finish the regular season with the best overall record and the first Eastern Conference team to win the title. Their play was based on teamwork, citizenship, dedication and unselfishness. The Shock set a league record with a 16-victory improvement over 2002; and Whereas, A WNBA record-crowd of more than 22,000 saw the Shock defeat the two- time defending champion Los Angeles Sparks by a score of 83-78 in the third and final game of the finals at the Palace of Auburn Hills. This accomplishment was the first time in professional sports a team won the title after having the worst record in the league the previous season; and Whereas, Detroit Shock Head Coach Bill Laimbeer was voted WNBA's Coach of the Year. He led the Shock to a league-best 25-9 record this season and worked tirelessly to instill energy and enthusiasm in the team; and Whereas, Shock forward Cheryl Ford was selected WNBA Rookie of the Year. -

2003 NCAA Women's Basketball Records Book

AwWin_WB02 10/31/02 4:47 PM Page 99 Award Winners All-American Selections ................................... 100 Annual Awards ............................................... 103 Division I First-Team All-Americans by Team..... 106 Divisions II and III First-Team All-Americans by Team ....................................................... 108 First-Team Academic All-Americans by Team.... 110 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners by Team ....................................................... 112 AwWin_WB02 10/31/02 4:47 PM Page 100 100 ALL-AMERICAN SELECTIONS All-American Selections Annette Smith, Texas; Marilyn Stephens, Temple; Joyce Division II: Jennifer DiMaggio, Pace; Jackie Dolberry, Kodak Walker, LSU. Hampton; Cathy Gooden, Cal Poly Pomona; Jill Halapin, Division II: Carla Eades, Central Mo. St.; Francine Pitt.-Johnstown; Joy Jeter, New Haven; Mary Naughton, Note: First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Women’s Perry, Quinnipiac; Stacey Cunningham, Shippensburg; Stonehill; Julie Wells, Northern Ky.; Vanessa Wells, West Basketball Coaches Association. Claudia Schleyer, Abilene Christian; Lorena Legarde, Port- Tex. A&M; Shannon Williams, Valdosta St.; Tammy Wil- son, Central Mo. St. 1975 land; Janice Washington, Valdosta St.; Donna Burks, Carolyn Bush, Wayland Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Dayton; Beth Couture, Erskine; Candy Crosby, Northeast Division III: Jessica Beachy, Concordia-M’head; Catie Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Harris, Ill.; Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Okla. Cleary, Pine Manor; Lesa Dennis, Emmanuel (Mass.); Delta St.; Jan Irby, William Penn; Ann Meyers, UCLA; Division III: Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Kaye Cross, Kimm Lacken, Col. of New Jersey; Louise MacDonald, St. Brenda Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Debbie Oing, Indiana; Colby; Sallie Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Elizabethtown; John Fisher; Linda Mason, Rust; Patti McCrudden, New Sue Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. St.; Susan Yow, Elon. -

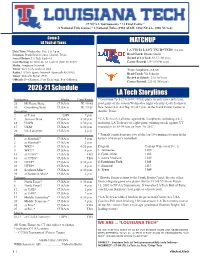

2020-21 Schedule MATCHUP LA Tech Storylines

2020-21 LOUISIANA TECH WOMEN’S BASKETBALL 27 NCAA Tournaments * 13 Final Fours * 8 National Title Games * 3 National Titles (1981 AIAW, 1982 NCAA, 1988 NCAA) Gamel 3 LA Tech at Texas MATCHUP LA TECH LADY TECHSTERS (2-0, 0-0) Date/Time: Wednesday, Dec. 2 at 7 p.m. Location: Frank Erwin Center (Austin, Texas) Head Coach: Brooke Stoehr Series History: LA Tech leads 8-3 Record at LA Tech: 68-57 (5th year) Last Meeting: #2 Texas 88, LA Tech 54 (Nov. 30, 2017) Career Record: 139-115 (9th year) Media: Longhorn Network Talent: Alex Loeb, Andrea Lloyd Texas Longhorns (2-0, 0-0) Radio: LA Tech Sports Network (Sportsalk 99.3 FM) Head Coach: Vic Schaefer Talent: Malcolm Butler (PxP) Record at School: 2-0 (1st Year) Officials: Dee Kantner, Scott Yarbrough, Roy Gulbeyan Career Record: 223-62 (9th year) 2020-21 Schedule LA Tech Storylines November Media Time/Result * Louisiana Tech (2-0, 0-0 C-USA) plays its only non-conference 25 McNeese State CUSA.tv W, 90-45 road game of the season Wednesday night when the Lady Techsters 30 Grambling State CUSA.tv W, 79-69 face Texas (2-0, 0-0 Big 12) at 7 p.m. at the Frank Erwin Center in December Austin, Texas. 2 at Texas LHN 7 p.m. 8 Jackson State CUSA.tv 6:30 p.m. * LA Tech is 8-3 all-time against the Longhorns, including a 4-1 14 UAPB CUSA.tv 6:30 p.m. in Austin. LA Tech saw its eight-game winning streak against UT 17 ULM CUSA.tv 6:30 p.m. -

USA (2-0) Vs. France (1-1)

2020 U.S. OLYMPIC WOMEN’S BASKETBALL TEAM USA (2-0) vs. France (1-1) JULY 30, 2021 | SAITAMA SUPER ARENA | 1:40 PM JT | 12:40 AM ET | USA NETWORK PROBABLE STARTERS 2019-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS (20-3) NO NAME PPG RPG APG CAPS 6 Sue Bird 1.5 4.0 9.5 153 2019 FIBA AMERICUP (6-0) 15 Brittney Griner 14.0 7.5 2.5 41 9/22 USA 110, Paraguay 31 10 Breanna Stewart 12.0 12.0 5.0 95 9/24 USA 88, Colombia 46 12 Diana Taurasi 10.5 1.5 1.5 140 9/25 USA 100, Argentina 50 9 A’ja Wilson 19.5 11.5 2.0 52 9/26 USA 89, Brazil 73 RESERVES 9/28 USA 78, Puerto Rico 54 9/29 USA 67, Canada 46 NO NAME PPG RPG APG CAPS 7 Ariel Atkins 0.0 0.0 0.0 16 2019 FALL TOUR (3-1) 14 Tina Charles 3.0 3.5 2.0 96 11/2 USA 95, No. 3 Stanford 80 11 Napheesa Collier 0.0 0.0 0.0 54* 11/4 USA 81, No. 7/6 Oregon State 58 5 Skylar Diggins-Smith 1.0 0.0 0.0 53* 11/7 USA 93, Texas A&M No. 6/7 63 13 Sylvia Fowles 6.5 4.5 0.5 89 11/9 No. 1/1 Oregon 93, USA 86 8 Chelsea Gray 6.0 2.0 3.0 16 4 Jewell Loyd 10.0 4.5 1.5 36* 2019 FIBA AMERICAS PRE-OLYMPIC NOTES: QUALIFYING TOURNAMENT (3-0) • Stats listed are from the 2020 Olympic Games.