Elijah Program 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joshua Cockayne Thesis.Pdf

The God-Relationship: A Kierkegaardian account of the Christian spiritual life Joshua Luke Cockayne PhD University of York Philosophy July 2016 Abstract By drawing on the writings of Søren Kierkegaard, I address the question of what it is to live in relationship with God. In answering this question, it is important to recognise that God, as he is described in the Christian tradition, is a personal God. For this reason, the account of the Christian spiritual life I outline is described as a life of coming to know God personally, rather than as a life of coming to know about God by learning about him. As I argue, a minimal condition for knowing God personally in this way is that an individual has a second-person experience of God. However, one of the barriers which prevents relationship with God from occurring in this life is that the human will is defective in such a way that human beings cannot will to be in union with God. Because of this problem, human beings cannot live in union with God in this life. And so, in order to allow for the possibility of union with God in the life to come, the human will must be repaired; consequently, one of the key tasks of the spiritual life is this task of repairing a person’s will by re-orienting it so that union with God is possible. Since a person cannot be in union with God in this life, it is important to give an account of what it is to be in relationship with God in the spiritual life. -

The Critical Reception of Beethoven's Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op

The Critical Reception of Beethoven’s Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op. 124 Translated and edited by Robin Wallace © 2020 by Robin Wallace All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-7348948-4-4 Center for Beethoven Research Boston University Contents Foreword 6 Op. 123. Missa Solemnis in D Major 123.1 I. P. S. 8 “Various.” Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 1 (21 January 1824): 34. 123.2 Friedrich August Kanne. 9 “Beethoven’s Most Recent Compositions.” Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung mit besonderer Rücksicht auf den österreichischen Kaiserstaat 8 (12 May 1824): 120. 123.3 *—*. 11 “Musical Performance.” Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode 9 (15 May 1824): 506–7. 123.4 Ignaz Xaver Seyfried. 14 “State of Music and Musical Life in Vienna.” Caecilia 1 (June 1824): 200. 123.5 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of May.” 15 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 26 (1 July 1824): col. 437–42. 3 contents 123.6 “Glances at the Most Recent Appearances in Musical Literature.” 19 Caecilia 1 (October 1824): 372. 123.7 Gottfried Weber. 20 “Invitation to Subscribe.” Caecilia 2 (Intelligence Report no. 7) (April 1825): 43. 123.8 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of March.” 22 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 29 (25 April 1827): col. 284. 123.9 “ .” 23 Allgemeiner musikalischer Anzeiger 1 (May 1827): 372–74. 123.10 “Various. The Eleventh Lower Rhine Music Festival at Elberfeld.” 25 Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 156 (7 June 1827). 123.11 Rheinischer Merkur no. 46 27 (9 June 1827). 123.12 Georg Christian Grossheim and Joseph Fröhlich. 28 “Two Reviews.” Caecilia 9 (1828): 22–45. -

Beethoven (1819-1823) (1770-1827)

Friday, May 10, 2019, at 8:00 PM Saturday, May 11, 2019, at 3:00 PM MISSA SOLEMNIS IN D, OP. 123 Ludwig van Beethoven (1819-1823) (1770-1827) Tami Petty, soprano Helen KarLoski, mezzo-soprano Dann CoakwelL, tenor Joseph Beutel, bass-baritone Kyrie GLoria Credo Sanctus and Benedictus* Agnus Dei * Jorge ÀviLa, violin solo Approximately 80 minutes, performed without intermission. PROGRAM NOTES The biographer Maynard SoLomon him to conceptuaLize the Missa as a work described the Life of Ludwig van of greater permanence and universaLity, a Beethoven (1770-1827) as “a series of keystone of his own musicaL and creative events unique in the history of personaL Legacy. mankind.” Foremost among these creative events is the Missa Solemnis The Kyrie and GLoria settings were (Op. 123), a work so intense, heartfeLt and largely complete by March of 1820, with originaL that it nearly defies the Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus and categorization. Agnus Dei foLLowing in Late 1820 and 1821. Beethoven continued to poLish the work Beethoven began the Missa in 1819 in through 1823, in the meantime response to a commission from embarking on a convoLuted campaign to Archduke RudoLf of Austria, youngest pubLish the work through a number of son of the Hapsburg emperor and a pupiL competing European houses. (At one and patron of the composer. The young point, he represented the existence of no aristocrat desired a new Mass setting for less than three Masses to various his enthronement as Archbishop of pubLishers when aLL were one and the Olmütz (modern day Olomouc, in the same.) A torrent of masterworks joined Czech RepubLic), scheduLed for Late the the Missa during this finaL decade of following year. -

A Study of Suffering in T~E Thought of S0ren Kierkegaard

A STUDY OF SUFFERING IN T~E THOUGHT OF S0REN KIERKEGAARD BY EDWARD ERIC IVOR GLASS SUBMITTED IN PART FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE OF RELIGION IN THE FACULTY OF ARTS AT THE UNIVERISTY OF DURBAN-WESTVILLE Supervisors Professor G.C. Oosthuizen Professor R. Singh DATE SUBMITTED 1 NOVEMBER 1987 CONTENTS Introduction The goal in truth through suffering The diale~tic - accepted choice through freedom 2 Examples, identification 3 Relevance of suffering .> .' 4 Impact 5 Life-long dimension 6 ~he individual in the moment 7 Understanding the ever-present immediacy of Suffering 8 Hum i I i ty 9 Loneliness 10 ~Challenge 11 S.K. the missioner. Hegel 12 S.K. the Catalyst 13 ;. S. K• and the Church 14 The enigmatic believer 16 :Suffering and the reader 18 ·Subjective action. The risk 19 Chapter 1. Kierkegaard's background. Influences on him. The development of thought amongst his precursors 22 The personal/emotional background Early years 23 Thought development 24 The Corsair 25 Attacks on Church .... death 26 The philosophical background 27 The individual - guilt The time factor 28 Inwardness 30 CONTENTS The precursors: 37 Pascal 38 Hume 43 Kant 46 Hamann 48 Hegel 51 Schleiermacher 58 von Schelling 60 Lessing 64 von Badaar 66 Locke 67 Voltaire 68 Socrates 69 Luther 69 The Bible 71 Phenomenology 73 Early tension 75 The melancholy youth 76 Angst 77 Maturing 78 The Student 79 Distrust develops 80 The Stages 81 The revelation of his prayers 83 Genuine existential suffering and love 85-87 Indirect Communication and the mystical 89 Presentiment 91 Blessed misery. -

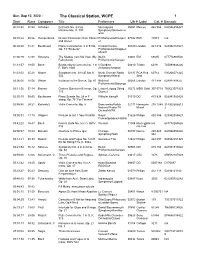

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Sep 13, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 07:52 Schubert Entr'acte No. 3 from Minneapolis 05051 Mercury 462 954 028946295427 Rosamunde, D. 797 Symphony/Skrowacze wski 00:10:2208:46 Humperdinck Dream Pantomime from Hansel Philharmonia/Klemper 07382 EMI 13073 n/a and Gretel er 00:20:0838:41 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Curzon/Vienna 04349 London 421 616 028942161627 Op. 73 "Emperor" Philharmonic/Knappert sbusch 01:00:19 12:38 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My Berlin 03600 EMI 69005 077776900520 Fatherland) Philharmonic/Karajan 01:13:5718:05 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in Il Giardino 04810 Teldec 6019 745099844226 F, BWV 1046 Armonico/Antonini 01:33:02 25:28 Mozart Symphony No. 39 in E flat, K. North German Radio 02135 RCA Red 60714 090266071425 543 Symphony/Wand Seal 02:00:0010:56 Weber Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65 National 00266 London 411 898 02894189820 Philharmonic/Bonynge 02:11:56 37:14 Brahms Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. Leister/Leipzig String 10273 MDG Gold 307 0719 760623071923 115 Quartet 02:50:1008:00 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 24 in F Wilhelm Kempff 01310 DG 415 834 028941583420 sharp, Op. 78 "For Therese" 02:59:40 29:21 Karlowicz Violin Concerto, Op. 8 Danczowka/Polish 02170 Harmonia 278 1088 314902505612 National Radio-TV Mundi 2 Orchestra/Wit 03:30:0111:19 Wagner Prelude to Act 1 from Parsifal Royal 01626 Philips 420 886 028942088627 Concertgebouw/Haitink 03:42:2016:47 Bach French Suite No. -

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra War and Peace

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra War and Peace Jane Glover, Music Director Jane Glover, conductor William Jon Gray, chorus director Soprano Violin 1 Flute Laura Amend Robert Waters, Mary Stolper Sunday, May 17, 2015, 7:30 PM Alyssa Bennett concertmaster Pick-Staiger Concert Hall, Evanston Bethany Clearfield Kevin Case Oboe Sarah Gartshore* Teresa Fream Robert Morgan, principal Monday, May 18, 2015, 7:30 PM Katelyn Lee Kathleen Brauer Peggy Michel Harris Theater, Chicago (Millennium Park) Hannah Dixon Michael Shelton McConnell Ann Palen Clarinet Sarah Gartshore, soprano Susan Nelson Steve Cohen, principal Kathryn Leemhuis, mezzo-soprano Anne Slovin Violin 2 Daniel Won Ryan Belongie, countertenor Alison Wahl Sharon Polifrone, Zach Finkelstein, tenor Emily Yiannias principal Bassoon Roderick Williams, baritone Fox Fehling William Buchman, Alto Ronald Satkiewicz principal Te Deum for the Victory of Dettingen, HWV 283 George Frideric Handel Ryan Belongie* Rika Seko Lewis Kirk (1685–1759) Julie DeBoer Paul Vanderwerf 1. Chorus: We praise Thee, o God Julia Elise Hardin Horn 2. Soli (alto, tenor) and Chorus: All the earth doth worship Thee Amanda Koopman Viola Jon Boen, principal 3. Chorus: To Thee all angels cry aloud Kathryn Leemhuis* Elizabeth Hagen, Neil Kimel 4. Chorus: To Thee Cherubim and Seraphim Maggie Mascal principal 5. Chorus: The glorious company of the apostles Emily Price Terri Van Valkinburgh Trumpet 6. Aria (baritone) and Chorus: Thou art the King of Glory Claudia Lasareff-Mironoff Barbara Butler, 7. Aria (baritone): When Thou tookest upon Thee Tenor Benton Wedge co-principal 8. Chorus: When Thou hadst overcome Madison Bolt Charles Geyer, 9. Trio (alto, tenor, baritone): Thou sittest at the right hand of God Zach Finkelstein* Cello co-principal 10. -

SAMUEL BARBER Evening During Term in the College Chapel and Presents an Annual Concert Series

559053bk Barber 15/6/06 9:51 pm Page 5 Choir of Ormond College, University of Melbourne Deborah Kayser Deborah Kayser performs in areas as diverse as ancient Byzantine chant, French and German Baroque song and In June and July of 2005 the Choir of Ormond College gave its eleventh international concert tour, visiting classical contemporary music, both scored and improvised. Her work has led her to tour regularly both within AMERICAN CLASSICS Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Poland and Italy. Other tours have included New Zealand, Singapore, Japan, Australia, and internationally to Europe and Asia. She has recorded, as soloist, on numerous CDs, and her work is Holland, England, Scotland, Switzerland and Belgium. These tours have received outspoken praise from the public frequently broadcast on ABC FM. As a member of Jouissance, and the contemporary music ensembles Elision and and critics alike. The choir was formed by its Director; Douglas Lawrence, Master of the Chapel Music, in 1982. Libra, she has performed radical interpretations of Byzantine and Medieval chant, and given premières of works There are 24 Choral Scholars: ten sopranos, four altos, four tenors, and six basses. The choir sings each Sunday written specifically for her voice by local and overseas composers. Her performance highlights include works by SAMUEL BARBER evening during term in the College chapel and presents an annual concert series. Each year a number of outside composers Liza Lim, Richard Barrett and Chris Dench, her collaboration with bassist Nick Tsiavos, and oratorio and engagements are undertaken. These have included concerts for the Australian Broadcasting Commission, Musica choral works with Douglas Lawrence. -

ALBAN Gerhardt ANNE-Marie Mcdermott

THE KINDLER FOUNDATION TRUST FUND iN tHE LIBRARY oF CONGRESS ALBAN GERHARDT ANNE-MARIE MCDERMOTT Saturday, January 16, 2016 ~ 2 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building In 1983 the KINDLER FOUNDATION TRUST FUND in the Library of Congress was established to honor cellist Hans Kindler, founder and first director of the National Symphony Orchestra, through concert presentations and commissioning of new works. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Saturday, January 16, 2016 — 2 pm THE KINDLER FOUNDATION TRUST FUND iN tHE LIBRARY oF CONGRESS ALBAN GERHARDT, CELLO ANNE-MARIE MCDERMOTT, PIANO • Program SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) Sonata for cello and piano, op. 6 (1932) Allegro ma non troppo Adagio—Presto—Adagio Allegro appassionato BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976) Sonata in C major for cello and piano, op. 65 (1960-1961) Dialogo Scherzo-pizzicato Elegia Marcia Moto perpetuo LUKAS FOSS (1922-2009) Capriccio (1946) iNtermission 1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918-1990) Three Meditations from Mass for cello and piano (1971) Meditation no. -

Graduate-Dissertations-21

Ph.D. Dissertations in Musicology University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Music 1939 – 2021 Table of Contents Dissertations before 1950 1939 1949 Dissertations from 1950 - 1959 1950 1952 1953 1955 1956 1958 1959 Dissertations from 1960 - 1969 1960 1961 1962 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 Dissertations from 1970 - 1979 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 Dissertations from 1980 - 1989 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 Dissertations from 1990 - 1999 1990 1991 1992 1994 1995 1996 1998 1999 Dissertations from 2000 - 2009 2000 2001 2002 2003 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Dissertations since 2010 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2018 2019 Dissertations since 2020 2020 2021 1939 Peter Sijer Hansen The Life and Works of Dominico Phinot (ca. 1510-ca. 1555) (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1949 Willis Cowan Gates The Literature for Unaccompanied Solo Violin (under the direction of Glen Haydon) Gwynn Spencer McPeek The Windsor Manuscript, British Museum, Egerton 3307 (under the direction of Glen Haydon) Wilton Elman Mason The Lute Music of Sylvius Leopold Weiss (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1950 Delbert Meacham Beswick The Problem of Tonality in Seventeenth-Century Music (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1952 Allen McCain Garrett The Works of William Billings (under the direction of Glen Haydon) Herbert Stanton Livingston The Italian Overture from A. Scarlatti to Mozart (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1953 Almonte Charles Howell, Jr. The French Organ Mass in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (under the direction of Jan Philip Schinhan) 1955 George E. -

A Conductor's Guide to Twentieth-Century Choral-Orchestral Works in English

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9314580 A conductor's guide to twentieth-century choral-orchestral works in English Green, Jonathan David, D.M.A. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1992 UMI 300 N. -

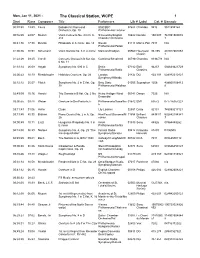

Mon, Jan 11, 2021 - the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Mon, Jan 11, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 13:59 Fauré Ballade for Piano and Stott/BBC 07688 Chandos 9416 9511594162 Orchestra, Op. 19 Philharmonic/Tortelier 00:16:2924:07 Mozart Violin Concerto No. 4 in D, K. Sitkovetsky/English 10822 Novalis 150 007 761991500072 218 Chamber Orchestra 7 00:41:36 17:30 Dvorak Rhapsody in A minor, Op. 14 Slovak 01118 Marco Polo 7013 N/A Philharmonic/Pešek 01:00:3620:53 Schumann Violin Sonata No. 3 in A minor Malikian/Kradjian 05560 Haenssler 98.355 401027601053 Classic 1 01:22:29 09:45 Corelli Concerto Grosso in B flat, Op. Cantilena/Shepherd 00794C Chandos 8336/7/8 N/A 6 No. 11 01:33:1426:09 Haydn Symphony No. 090 in C Berlin 07182 EMI 94237 094639423729 Philharmonic/Rattle Classics 02:00:53 10:19 Mendelssohn Hebrides Overture, Op. 26 London 01435 DG 423 104 028942310421 Symphony/Abbado 02:12:1235:57 Fibich Symphony No. 2 in E flat, Op. Brno State 01355 Supraphon 1256 498800106413 38 Philharmonic/Waldhan 8 s 02:49:0910:16 Handel Trio Sonata in B flat, Op. 2 No. Heinz Holliger Wind 00341 Denon 7026 N/A 3 Ensemble 03:00:5509:48 Weber Overture to Der Freischutz Philharmonia/Sawallisc 01642 EMI 69572 077776957227 h 03:11:4301:06 Heller Etude Lily Laskine 02591 Erato 92131 745099213121 03:13:49 45:30 Brahms Piano Quartet No. 2 in A, Op. Han/Faust/Giuranna/M 11858 Brilliant 94381/1 502842194381 26 eunier Classics 7 04:00:4910:11 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. -

Divine Violence and Divine Sovereignty

Divine Violence and Divine Sovereignty DIVINE VIOLENCE AND DIVINE SOVEREIGNTY: KIERKEGAARD AND THE BINDING OF ISAAC By H. MATTHEW LEE, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by H. Matthew Lee, September 2015 i McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2015) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Divine Violence and Divine Sovereignty: Kierkegaard and the Binding of Isaac AUTHOR: H. Matthew Lee SUPERVISOR: Dr. P. Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: 111 ii Abstract This thesis examines the concept of sovereignty, as developed by the jurist Carl Schmitt, and argues that this concept helps to elucidate the very core of Fear and Trembling, a text that continues to be heavily misunderstood despite its great fame in Western thought today. Through a close examination of Schmitt’s formulation of the concept of sovereignty and the method by which he develops this concept through Kierkegaard’s concept of the exception in Repetition, I show how Kierkegaard influenced Schmitt and also how Schmitt’s interpretation is useful for reading Fear and Trembling. However, I also show how Schmitt’s usage of Kierkegaard, despite its ingenuity, is misleading, and present a more faithful reading of Kierkegaard’s concept of exception. With this reorientation, I in turn critique Schmitt’s methodology and the way he understands sovereignty. Following this reinterpretation of sovereignty, I examine the text of Genesis 22 and Fear and Trembling and examine the theological themes that ground the narrative of the Binding of Isaac. I argue that the problem of the Binding and the arguments set forth in Fear and Trembling cannot be understood adequately without a clear awareness of the image of reality that is presupposed.