Fourier Optics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Green-Function Transform and Wave Propagation

1 The Green-function transform and wave propagation Colin J. R. Sheppard,1 S. S. Kou2 and J. Lin2 1Department of Nanophysics, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Genova 16163, Italy 2School of Physics, University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia *Corresponding author: [email protected] PACS: 0230Nw, 4120Jb, 4225Bs, 4225Fx, 4230Kq, 4320Bi Abstract: Fourier methods well known in signal processing are applied to three- dimensional wave propagation problems. The Fourier transform of the Green function, when written explicitly in terms of a real-valued spatial frequency, consists of homogeneous and inhomogeneous components. Both parts are necessary to result in a pure out-going wave that satisfies causality. The homogeneous component consists only of propagating waves, but the inhomogeneous component contains both evanescent and propagating terms. Thus we make a distinction between inhomogenous waves and evanescent waves. The evanescent component is completely contained in the region of the inhomogeneous component outside the k-space sphere. Further, propagating waves in the Weyl expansion contain both homogeneous and inhomogeneous components. The connection between the Whittaker and Weyl expansions is discussed. A list of relevant spherically symmetric Fourier transforms is given. 2 1. Introduction In an impressive recent paper, Schmalz et al. presented a rigorous derivation of the general Green function of the Helmholtz equation based on three-dimensional (3D) Fourier transformation, and then found a unique solution for the case of a source (Schmalz, Schmalz et al. 2010). Their approach is based on the use of generalized functions and the causal nature of the out-going Green function. Actually, the basic principle of their method was described many years ago by Dirac (Dirac 1981), but has not been widely adopted. -

Approximate Separability of Green's Function for High Frequency

APPROXIMATE SEPARABILITY OF GREEN'S FUNCTION FOR HIGH FREQUENCY HELMHOLTZ EQUATIONS BJORN¨ ENGQUIST AND HONGKAI ZHAO Abstract. Approximate separable representations of Green's functions for differential operators is a basic and an important aspect in the analysis of differential equations and in the development of efficient numerical algorithms for solving them. Being able to approx- imate a Green's function as a sum with few separable terms is equivalent to the existence of low rank approximation of corresponding discretized system. This property can be explored for matrix compression and efficient numerical algorithms. Green's functions for coercive elliptic differential operators in divergence form have been shown to be highly separable and low rank approximation for their discretized systems has been utilized to develop efficient numerical algorithms. The case of Helmholtz equation in the high fre- quency limit is more challenging both mathematically and numerically. In this work, we develop a new approach to study approximate separability for the Green's function of Helmholtz equation in the high frequency limit based on an explicit characterization of the relation between two Green's functions and a tight dimension estimate for the best linear subspace approximating a set of almost orthogonal vectors. We derive both lower bounds and upper bounds and show their sharpness for cases that are commonly used in practice. 1. Introduction Given a linear differential operator, denoted by L, the Green's function, denoted by G(x; y), is defined as the fundamental solution in a domain Ω ⊆ Rn to the partial differ- ential equation 8 n < LxG(x; y) = δ(x − y); x; y 2 Ω ⊆ R (1) : with boundary condition or condition at infinity; where δ(x − y) is the Dirac delta function denoting an impulse source point at y. -

Waves and Imaging Class Notes - 18.325

Waves and Imaging Class notes - 18.325 Laurent Demanet Draft December 20, 2016 2 Preface In the margins of this text we use • the symbol (!) to draw attention when a physical assumption or sim- plification is made; and • the symbol ($) to draw attention when a mathematical fact is stated without proof. Thanks are extended to the following people for discussions, suggestions, and contributions to early drafts: William Symes, Thibaut Lienart, Nicholas Maxwell, Pierre-David Letourneau, Russell Hewett, and Vincent Jugnon. These notes are accompanied by computer exercises in Python, that show how to code the adjoint-state method in 1D, in a step-by-step fash- ion, from scratch. They are provided by Russell Hewett, as part of our software platform, the Python Seismic Imaging Toolbox (PySIT), available at http://pysit.org. 3 4 Contents 1 Wave equations 9 1.1 Physical models . .9 1.1.1 Acoustic waves . .9 1.1.2 Elastic waves . 13 1.1.3 Electromagnetic waves . 17 1.2 Special solutions . 19 1.2.1 Plane waves, dispersion relations . 19 1.2.2 Traveling waves, characteristic equations . 24 1.2.3 Spherical waves, Green's functions . 29 1.2.4 The Helmholtz equation . 34 1.2.5 Reflected waves . 35 1.3 Exercises . 39 2 Geometrical optics 45 2.1 Traveltimes and Green's functions . 45 2.2 Rays . 49 2.3 Amplitudes . 52 2.4 Caustics . 54 2.5 Exercises . 55 3 Scattering series 59 3.1 Perturbations and Born series . 60 3.2 Convergence of the Born series (math) . 63 3.3 Convergence of the Born series (physics) . -

The Gauss-Airy Functions and Their Properties

Annals of the University of Craiova, Mathematics and Computer Science Series Volume 43(2), 2016, Pages 119{127 ISSN: 1223-6934 The Gauss-Airy functions and their properties Alireza Ansari Abstract. In this paper, in connection with the generating function of three-variable Hermite polynomials, we introduce the Gauss-Airy function Z 1 3 1 −yt2 zt GAi(x; y; z) = e cos(xt + )dt; y ≥ 0; x; z 2 R: π 0 3 Some properties of this function such as behaviors of zeros, orthogonal relations, corresponding inequalities and their integral transforms are investigated. Key words and phrases. Gauss-Airy function, Airy function, Inequality, Orthogonality, Integral transforms. 1. Introduction We consider the three-variable Hermite polynomials [ n ] [ n−3j ] X3 X2 zj yk H (x; y; z) = n! xn−3j−2k; (1) 3 n j! k!(n − 2k)! j=0 k=0 2 3 as the coefficient set of the generating function ext+yt +zt 1 n 2 3 X t ext+yt +zt = H (x; y; z) : (2) 3 n n! n=0 For the first time, these polynomials [8] and their generalization [9] was introduced by Dattoli et al. and later Torre [10] used them to describe the behaviors of the Hermite- Gaussian wavefunctions in optics. These are wavefunctions appeared as Gaussian apodized Airy polynomials [3,7] in elegant and standard forms. Also, similar families to the generating function (2) have been stated in literature, see [11, 12]. Now in this paper, it is our motivation to introduce the Gauss-Airy function derived from operational relation 2 3 y d +z d n 3Hn(x; y; z) = e dx2 dx3 x : (3) For this purpose, in view of the operational calculus of the Mellin transform [4{6], we apply the following integral representation 1 2 3 Z eys +zs = esξGAi(ξ; y; z) dξ; (4) −∞ Received February 28, 2015. -

Implementation of Airy Function Using Graphics Processing Unit (GPU)

ITM Web of Conferences 32, 03052 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/itmconf/20203203052 ICACC-2020 Implementation of Airy function using Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) Yugesh C. Keluskar1, Megha M. Navada2, Chaitanya S. Jage3 and Navin G. Singhaniya4 Department of Electronics Engineering, Ramrao Adik Institute of Technology, Nerul, Navi Mumbai. Email : [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Special mathematical functions are an integral part Airy function is the solution to Airy differential equa- of Fractional Calculus, one of them is the Airy function. But tion,which has the following form [22]: it’s a gruelling task for the processor as well as system that is constructed around the function when it comes to evaluating the d2y special mathematical functions on an ordinary Central Processing = xy (1) Unit (CPU). The Parallel processing capabilities of a Graphics dx2 processing Unit (GPU) hence is used. In this paper GPU is used to get a speedup in time required, with respect to CPU time for It has its applications in classical physics and mainly evaluating the Airy function on its real domain. The objective quantum physics. The Airy function also appears as the so- of this paper is to provide a platform for computing the special lution to many other differential equations related to elasticity, functions which will accelerate the time required for obtaining the heat equation, the Orr-Sommerfield equation, etc in case of result and thus comparing the performance of numerical solution classical physics. While in the case of Quantum physics,the of Airy function using CPU and GPU. -

Summary of Wave Optics Light Propagates in Form of Waves Wave

Summary of Wave Optics light propagates in form of waves wave equation in its simplest form is linear, which gives rise to superposition and separation of time and space dependence (interference, diffraction) waves are characterized by wavelength and frequency propagation through media is characterized by refractive index n, which describes the change in phase velocity media with refractive index n alter velocity, wavelength and wavenumber but not frequency lenses alter the curvature of wavefronts Optoelectronic, 2007 – p.1/25 Syllabus 1. Introduction to modern photonics (Feb. 26), 2. Ray optics (lens, mirrors, prisms, et al.) (Mar. 7, 12, 14, 19), 3. Wave optics (plane waves and interference) (Mar. 26, 28), 4. Beam optics (Gaussian beam and resonators) (Apr. 9, 11, 16), 5. Electromagnetic optics (reflection and refraction) (Apr. 18, 23, 25), 6. Fourier optics (diffraction and holography) (Apr. 30, May 2), Midterm (May 7-th), 7. Crystal optics (birefringence and LCDs) (May 9, 14), 8. Waveguide optics (waveguides and optical fibers) (May 16, 21), 9. Photon optics (light quanta and atoms) (May 23, 28), 10. Laser optics (spontaneous and stimulated emissions) (May 30, June 4), 11. Semiconductor optics (LEDs and LDs) (June 6), 12. Nonlinear optics (June 18), 13. Quantum optics (June 20), Final exam (June 27), 14. Semester oral report (July 4), Optoelectronic, 2007 – p.2/25 Paraxial wave approximation paraxial wave = wavefronts normals are paraxial rays U(r) = A(r)exp(−ikz), A(r) slowly varying with at a distance of λ, paraxial Helmholtz equation -

Simple and Robust Method for Determination of Laser Fluence

Open Research Europe Open Research Europe 2021, 1:7 Last updated: 30 JUN 2021 METHOD ARTICLE Simple and robust method for determination of laser fluence thresholds for material modifications: an extension of Liu’s approach to imperfect beams [version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 2 approved with reservations] Mario Garcia-Lechuga 1,2, David Grojo 1 1Aix Marseille Université, CNRS, LP3, UMR7341, Marseille, 13288, France 2Departamento de Física Aplicada, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, 28049, Spain v1 First published: 24 Mar 2021, 1:7 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.13073.1 Latest published: 25 Jun 2021, 1:7 https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.13073.2 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract The so-called D-squared or Liu’s method is an extensively applied 1 2 3 approach to determine the irradiation fluence thresholds for laser- induced damage or modification of materials. However, one of the version 2 assumptions behind the method is the use of an ideal Gaussian profile (revision) report that can lead in practice to significant errors depending on beam 25 Jun 2021 imperfections. In this work, we rigorously calculate the bias corrections required when applying the same method to Airy-disk like version 1 profiles. Those profiles are readily produced from any beam by 24 Mar 2021 report report report insertion of an aperture in the optical path. Thus, the correction method gives a robust solution for exact threshold determination without any added technical complications as for instance advanced 1. Laurent Lamaignere , CEA-CESTA, Le control or metrology of the beam. Illustrated by two case-studies, the Barp, France approach holds potential to solve the strong discrepancies existing between the laser-induced damage thresholds reported in the 2. -

Fourier Optics

Fourier Optics 1 Background Ray optics is a convenient tool to determine imaging characteristics such as the location of the image and the image magni¯cation. A complete description of the imaging system, however, requires the wave properties of light and associated processes like di®raction to be included. It is these processes that determine the resolution of optical devices, the image contrast, and the e®ect of spatial ¯lters. One possible wave-optical treatment considers the Fourier spectrum (space of spatial frequencies) of the object and the transmission of the spectral components through the optical system. This is referred to as Fourier Optics. A perfect imaging system transmits all spectral frequencies equally. Due to the ¯nite size of apertures (for example the ¯nite diameter of the lens aperture) certain spectral components are attenuated resulting in a distortion of the image. Specially designed ¯lters on the other hand can be inserted to modify the spectrum in a prede¯ned manner to change certain image features. In this lab you will learn the principles of spatial ¯ltering to (i) improve the quality of laser beams, and to (ii) remove undesired structures from images. To prepare for the lab, you should review the wave-optical treatment of the imaging process (see [1], Chapters 6.3, 6.4, and 7.3). 2 Theory 2.1 Spatial Fourier Transform Consider a two-dimensional object{ a slide, for instance that has a ¯eld transmission function f(x; y). This transmission function carries the information of the object. A (mathematically) equivalent description of this object in the Fourier space is based on the object's amplitude spectrum ZZ 1 F (u; v) = f(x; y)ei2¼ux+i2¼vydxdy; (1) (2¼)2 where the Fourier coordinates (u; v) have units of inverse length and are called spatial frequencies. -

Diffraction Fourier Optics

Lab 3: Diffraction & Fourier Optics This week in lab, we will continue our study of wave optics by looking at diffraction and Fourier optics. As you may recall from Lab 1, the Fourier transform gives us a way to go back and forth between time domain and frequency domain. Here we will explore how Fourier transforms are useful in optics. Learning Objectives: In this lab, students will: • Learn how to understand diffraction by extending the concept of interference (Huygens' principle) • Learn how spatial Fourier transforms arise in optical systems: o Lenses o Diffraction gratings. • Learn how to change an image by manipulating its Fourier transform. Huygen’s Principle Think back to the Pre-Lab assignment. You played around with the wave simulator (http://falstad.com/ripple/). Here you saw that we can create waves by arranging point sources in a certain way. It's done in technological applications like antenna arrays where you want to create a radio wave going in a certain direction. In ultrasound probes of the body an array of acoustic sources is used to create a wave that focuses at a certain point. In the simulation we used sources with the same phase, but if you vary the phase, you can also move the focused point around. In 1678, Huygens figured out that you could calculate how a wave propagates by making a cut in space and measuring the phase and amplitude everywhere on that plane. Then you place point emitters on the plane with the same amplitude and phase as you measured. The radiation from these point sources adds up to exactly the same wave you had coming in (Figure 1). -

On Airy Solutions of the Second Painlevé Equation

On Airy Solutions of the Second Painleve´ Equation Peter A. Clarkson School of Mathematics, Statistics and Actuarial Science, University of Kent, Canterbury, CT2 7NF, UK [email protected] October 18, 2018 Abstract In this paper we discuss Airy solutions of the second Painleve´ equation (PII) and two related equations, the Painleve´ XXXIV equation (P34) and the Jimbo-Miwa-Okamoto σ form of PII (SII), are discussed. It is shown that solutions which depend only on the Airy function Ai(z) have a completely difference structure to those which involve a linear combination of the Airy functions Ai(z) and Bi(z). For all three equations, the special solutions which depend only on Ai(t) are tronquee´ solutions, i.e. they have no poles in a sector of the complex plane. Further for both P34 and SII, it is shown that amongst these tronquee´ solutions there is a family of solutions which have no poles on the real axis. Dedicated to Mark Ablowitz on his 70th birthday 1 Introduction The six Painleve´ equations (PI–PVI) were first discovered by Painleve,´ Gambier and their colleagues in an investigation of which second order ordinary differential equations of the form d2q dq = F ; q; z ; (1.1) dz2 dz where F is rational in dq=dz and q and analytic in z, have the property that their solutions have no movable branch points. They showed that there were fifty canonical equations of the form (1.1) with this property, now known as the Painleve´ property. Further Painleve,´ Gambier and their colleagues showed that of these fifty equations, forty-four can be reduced to linear equations, solved in terms of elliptic functions, or are reducible to one of six new nonlinear ordinary differential equations that define new transcendental functions, see Ince [1]. -

15C Sp16 Fourier Intro

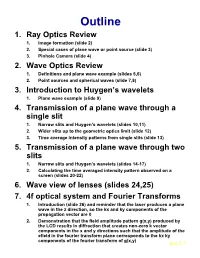

Outline 1. Ray Optics Review 1. Image formation (slide 2) 2. Special cases of plane wave or point source (slide 3) 3. Pinhole Camera (slide 4) 2. Wave Optics Review 1. Definitions and plane wave example (slides 5,6) 2. Point sources and spherical waves (slide 7,8) 3. Introduction to Huygen’s wavelets 1. Plane wave example (slide 9) 4. Transmission of a plane wave through a single slit 1. Narrow slits and Huygen’s wavelets (slides 10,11) 2. Wider slits up to the geometric optics limit (slide 12) 3. Time average intensity patterns from single slits (slide 13) 5. Transmission of a plane wave through two slits 1. Narrow slits and Huygen’s wavelets (slides 14-17) 2. Calculating the time averaged intensity pattern observed on a screen (slides 20-22) 6. Wave view of lenses (slides 24,25) 7. 4f optical system and Fourier Transforms 1. Introduction (slide 26) and reminder that the laser produces a plane wave in the z direction, so the kx and ky components of the propagation vector are 0 2. Demonstration that the field amplitude pattern g(x,y) produced by the LCD results in diffraction that creates non-zero k vector components in the x and y directions such that the amplitude of the efield in the fourier transform plane corresponds to the kx ky components of the fourier transform of g(x,y) Lec 2 :1 Ray Optics Intro Assumption: Light travels in straight lines Ray optics diagrams show the straight lines along which the light propagates Rules for a converging lens with focal length f, with the optic axis defined as the line that goes through the center of the lens perpendicular to the plane containing the lens: 1. -

Fourier Optics

Fourier optics 15-463, 15-663, 15-862 Computational Photography http://graphics.cs.cmu.edu/courses/15-463 Fall 2017, Lecture 28 Course announcements • Any questions about homework 6? • Extra office hours today, 3-5pm. • Make sure to take the three surveys: 1) faculty course evaluation 2) TA evaluation survey 3) end-of-semester class survey • Monday are project presentations - Do you prefer 3 minutes or 6 minutes per person? - Will post more details on Piazza. - Also please return cameras on Monday! Overview of today’s lecture • The scalar wave equation. • Basic waves and coherence. • The plane wave spectrum. • Fraunhofer diffraction and transmission. • Fresnel lenses. • Fraunhofer diffraction and reflection. Slide credits Some of these slides were directly adapted from: • Anat Levin (Technion). Scalar wave equation Simplifying the EM equations Scalar wave equation: • Homogeneous and source-free medium • No polarization 1 휕2 훻2 − 푢 푟, 푡 = 0 푐2 휕푡2 speed of light in medium Simplifying the EM equations Helmholtz equation: • Either assume perfectly monochromatic light at wavelength λ • Or assume different wavelengths independent of each other 훻2 + 푘2 ψ 푟 = 0 2휋푐 −푗 푡 푢 푟, 푡 = 푅푒 ψ 푟 푒 휆 what is this? ψ 푟 = 퐴 푟 푒푗휑 푟 Simplifying the EM equations Helmholtz equation: • Either assume perfectly monochromatic light at wavelength λ • Or assume different wavelengths independent of each other 훻2 + 푘2 ψ 푟 = 0 Wave is a sinusoid at frequency 2휋/휆: 2휋푐 −푗 푡 푢 푟, 푡 = 푅푒 ψ 푟 푒 휆 ψ 푟 = 퐴 푟 푒푗휑 푟 what is this? Simplifying the EM equations Helmholtz equation: