Julia Krueger. Prairie Pots and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Saskatchewan

SASKATCHEWAN RV PARKS & CAMPGROUNDS RECOMMENDED BY THE NRVOA TABLE OF CONTENTS Assiniboia Assiniboia Regional Park & Golf Course Battleford Eiling Kramer Campground Bengough Bengough Campground Big Beaver Big Beaver Campground Blaine Lake Martins Lake Regional Park Bulyea Rowans Ravine Candle Lake Sandy Bay Campground Canora Canora Campground Carlyle Moose Mountain Carrot River Carrot River Overnite Park Chelan Fishermans Cove Christopher Lake Anderson Point Campground Churchbridge Churchbridge Campground Christopher Lake Murray Point Campground Cochin The Battlefords Provincial Park Craik Craik & District Regional Park Cut Bank Danielson Campground Canada | NRVOA Recommended RV Parks & Campgrounds: 2019 Return To Table of Contents 2 Cut Knife Tomahawk Campground Davidson Davidson Campground Dinsmore Dinsmore Campground Dorintosh Flotten Lake North Dorintosh Flotten Lake South Dorintosh Greig Lake Dorintosh Kimball Lake Dorintosh Matheson Campground Dorintosh Mistohay Campground Dorintosh Murray Doell Campground Dundurn Blackstrap Campground Eastend Eastend Town Park Eston Eston Riverside Regional Park Elbow Douglas Campground Fishing Lake Fishing Lake Regional Park Glaslyn Little Loon Regional Park Govan Last Mountain Regional Park Grenfell Crooked Lake Campground Grenfell Grenfell Recreational Park Canada | NRVOA Recommended RV Parks & Campgrounds: 2019 Return To Table of Contents 3 Gull Lake Antelope Lake Campground Gull Lake Gull Lake Campground Harris Crystal Beach Regional Park Humboldt Waldsea Lake Regional Park Kamsack Duck Mountain -

Healthy Beaches Report

Saskatchewan Recreational Water Sampling Results to July 8, 2019 Water is Caution. Water Water is not Data not yet suitable for quality issues suitable for available/Sampling swimming observed swimming complete for season Legend: Recreational water is considered to be microbiologically safe for swimming when single sample result contains less than 400 E.coli organisms in 100 milliliters (mLs) of water, when the average (geometric mean) of five samples is under 200 E.coli/100 mLs, and/or when significant risk of illness is absent. Caution. A potential blue-green algal bloom was observed in the immediate area. Swimming is not recommended; contact with beach and access to facilities is not restricted. Resampling of the recreational water is required. Swimming Advisory issued. A single sample result containing ≥400 E.coli/100 mLs, an average (geometric mean) of five samples is >200 E.coli/100 mLs, an exceedance of the guideline value for cyanobacteria or their toxins >20 µg/L and/or a cyanobacteria bloom has been reported. Note: Sampling is typically conducted from June – August. Not all public swimming areas in Saskatchewan are monitored every year. Historical data and an annual environmental health assessment may indicate that only occasional sampling is necessary. If the quality of the area is deteriorating, then monitoring of the area will occur. This approach allows health officials to concentrate their resources on beaches of questionable quality. Every recreational area is sampled at least once every five years. Factors affecting the microbiological quality of a water body at any given time include type and periodicity of contamination events, time of day, recent weather conditions, number of users of the water body and, physical characteristics of the area. -

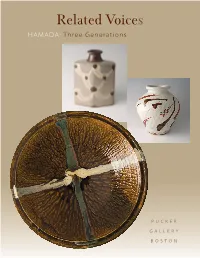

Related Voices Hamada: Three Generations

Related Voices HAMADA: Three Generations PUCKER GALLERY BOSTON Tomoo Hamada Shoji Hamada Bottle Obachi (Large Bowl), 1960-69 Black and kaki glaze with akae decoration Ame glaze with poured decoration 12 x 8 ¼ x 5” 4 ½ x 20 x 20” HT132 H38** Shinsaku Hamada Vase Ji glaze with tetsue and akae decoration Shoji Hamada 9 ¾ x 5 ¼ x 5 ¼” Obachi (Large Bowl), ca. 1950s HS36 Black glaze with trailing decoration 5 ½ x 23 x 23” H40** *Box signed by Shoji Hamada **Box signed by Shinsaku Hamada All works are stoneware. Three Voices “To work with clay is to be in touch with the taproot of life.’’ —Shoji Hamada hen one considers ceramic history in its broadest sense a three-generation family of potters isn’t particularly remarkable. Throughout the world potters have traditionally handed down their skills and knowledge to their offspring thus Wmaintaining a living history that not only provided a family’s continuity and income but also kept the traditions of vernacular pottery-making alive. The long traditions of the peasant or artisan potter are well documented and can be found in almost all civilizations where the generations are to be numbered in the tens or twenties or even higher. In Africa, South America and in Asia, styles and techniques remained almost unaltered for many centuries. In Europe, for example, the earthenware tradition existed from the early Middle Ages to the very beginning of the 20th century. Often carried on by families primarily involved in farming, it blossomed into what we would now call the ‘slipware’ tradition. The Toft family was probably the best known makers of slipware in Staffordshire. -

The Leach Pottery: 100 Years on from St Ives

The Leach Pottery: 100 years on from St Ives Exhibition handlist Above: Bernard Leach, pilgrim bottle, stoneware, 1950–60s Crafts Study Centre, 2004.77, gift of Stella and Nick Redgrave Introduction The Leach Pottery was established in St Ives, Cornwall in the year 1920. Its founders were Bernard Leach and his fellow potter Shoji Hamada. They had travelled together from Japan (where Leach had been living and working with his wife Muriel and their young family). Leach was sponsored by Frances Horne who had set up the St Ives Handicraft Guild, and she loaned Leach £2,500 as capital to buy land and build a small pottery, as well as a sum of £250 for three years to help with running costs. Leach identified a small strip of land (a cow pasture) at the edge of St Ives by the side of the Stennack stream, and the pottery was constructed using local granite. A tiny room was reserved for Hamada to sleep in, and Hamada himself built a climbing kiln in the oriental style (the first in the west, it was claimed). It was a humble start to one of the great sites of studio pottery. The Leach Pottery celebrates its centenary year in 2020, although the extensive programme of events and exhibitions planned in Britain and Japan has been curtailed by the impact of Covid-19. This exhibition is the tribute of the Crafts Study Centre to the history, legacy and continuing significance of The Leach Pottery, based on the outstanding collections and archives relating firstly to Bernard Leach. -

Ted Godwin: Last of the Regina Five

TED GODWIN: LAST OF THE REGINA FIVE FOLDFORMING: OF LIGHT AND LUSTRE Fall 2012 ANACHRONISMS IN CLAY BEES IN BERLIN ACAD IN ACTION FALL.2012 | ACAD Publisher External Relations Statements, opinions and Account Director Stephanie Hutchinson viewpoints expressed by the Managing Editor Miles Durrie writers of this publication do Creative Director Anders Knudsen not necessarily represent the (Diploma in Visual Communications, 1988) views of the publisher. Art Director Venessa Brewer (Bachelor of Design, 2002) Alberta College of Art + Design Contributors Kelley Abbey, Shelley Arnusch, in partnership with RedPoint Carol Beecher, Miles Durrie, Kim Alison Media & Marketing Solutions. Fraser, Mackenzie Frère, Kevin Kurytnik, Alison Miyauchi, Jared Sych, Lori Van Copyright 2012 by RedPoint Rooijen, Colin Way Media Group Inc. No part of this Project Manager Kelly Trinh publication may be reproduced Production Manager Mike Matovich without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Illustration Karen Klassen BFA Print Media, 2005 To view more of Karen’s work go to www. karenklassen.com 100, 1900 – 11th Street SE Alberta College of Art + Design Calgary, Alberta T2G 3G2 1407 – 14th Avenue NW Phone: 403.240.9055 Calgary, Alberta T2N 4R3 Media & Marketing Solutions redpointmedia.ca Phone: 403.284.7600 TRAVEL TO THE ANCIENT STONE VILLAGE OF LARAOS, PERU AND ITS SPECTACULAR STONE TERRACES. 14 DAYS OF ESCORTED DAY TRIPS INTO THE SURROUNDING NATIONAL PARK WILL CONCLUDE OVERNIGHT AT A HISTORIC PLANTATION, NOW RENOWNED AS A FINE DINING DESTINATION. -

The National Gallery of Canada: a Hundred Years of Exhibitions: List and Index

Document generated on 09/28/2021 7:08 p.m. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review The National Gallery of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions List and Index Garry Mainprize Volume 11, Number 1-2, 1984 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1074332ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1074332ar See table of contents Publisher(s) UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des universités du Canada) ISSN 0315-9906 (print) 1918-4778 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Mainprize, G. (1984). The National Gallery of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions: List and Index. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 11(1-2), 3–78. https://doi.org/10.7202/1074332ar Tous droits réservés © UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Association d'art des universités du Canada), 1984 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ The National Gallery of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions — List and Index — GARRY MAINPRIZE Ottawa The National Gallerv of Canada can date its February 1916, the Gallery was forced to vacate foundation to the opening of the first exhibition of the muséum to make room for the parliamentary the Canadian Academy of Arts at the Clarendon legislators. -

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism by Matthew Purvis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Matthew Purvis i Abstract This dissertation concerns the relation between eroticism and nationalism in the work of a set of English Canadian artists in the mid-1960s-70s, namely John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, and Joyce Wieland. It contends that within their bodies of work there are ways of imagining nationalism and eroticism that are often formally or conceptually interrelated, either by strategy or figuration, and at times indistinguishable. This was evident in the content of their work, in the models that they established for interpreting it and present in more and less overt forms in some of the ways of imagining an English Canadian nationalism that surrounded them. The dissertation contextualizes the three artists in the terms of erotic art prevalent in the twentieth century and makes a case for them as part of a uniquely Canadian mode of decadence. Constructing my case largely from the published and unpublished writing of the three subjects and how these played against their reception, I have attempted to elaborate their artistic models and processes, as well as their understandings of eroticism and nationalism, situating them within the discourses on English Canadian nationalism and its potentially morbid prospects. Rather than treating this as a primarily cultural or socio-political issue, it is treated as both an epistemic and formal one. -

Lowe, W. D. High School Yearbook 1962-1963

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Essex County (Ontario) High School Yearbooks Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive 1963 Lowe, W. D. High School Yearbook 1962-1963 Lowe, W. D. High School (Windsor, Ontario) Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/essexcountyontariohighschoolyearbooks Part of the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Lowe, W. D. High School (Windsor, Ontario), "Lowe, W. D. High School Yearbook 1962-1963" (1963). Essex County (Ontario) High School Yearbooks. 90. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/essexcountyontariohighschoolyearbooks/90 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Essex County (Ontario) High School Yearbooks by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r R 373. 71332 LOW ...... {,llJ. t()/{/(J "l&t'kt11/ Essex County Branch of The Ontario Genealogical Society (EssexOGS) Active Members: Preserving Family History; Networking & Collaborating; Advocates for Archives and Cemeteries This yearbook was scanned by the Essex County Branch of The Ontario Genealogical Society in conjunction with the Leddy Library on the campus of the University of Windsor for the owners of the book. The EssexOGS yearbook scanning project is for preservation and family history research purposes by the Essex County Branch membership. This document is made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder and cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. -

Bernard Leach and British Columbian Pottery: an Historical Ethnography of a Taste Culture

BERNARD LEACH AND BRITISH COLUMBIAN POTTERY: AN HISTORICAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF A TASTE CULTURE by Nora E. Vaillant B. A. Swarthmore College, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Department of Anthropology and Sociology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia October 2002 © Nora E. Vaillant, 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of J^j'thiA^^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This thesis presents an historical ethnography of the art world and the taste culture that collected the west coast or Leach influenced style of pottery in British Columbia. This handmade functional style of pottery traces its beginnings to Vancouver in the 1950s and 1960s, and its emergence is embedded in the cultural history of the city during that era. The development of this pottery style is examined in relation to the social network of its founding artisans and its major collectors. The Vancouver potters Glenn Lewis, Mick Henry and John Reeve apprenticed with master potter Bernard Leach in England during the late fifties and early sixties. -

14Th Annual Report the Canada Council 1970-1971

1 14th Annual Report The Canada Council 1970-1971 Honourable Gérard Pelletier Secretary of State of Canada Ottawa, Canada Sir, I have the honour to transmit herewith the Annual Report of the Canada Council, for submission to Parliament, as required by section 23 of the Canada Council Act (5-6 Elizabeth Ii, 1957, Chap. 3) for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1971. I am, Sir, Yours very truly, John G. Prentice, Chairman. June 341971 3 Contents The Arts The Humanities and Social Sciences Other Programs 10 Introduction 50 Levels of Subsidy, 1966-67 to 1970-71 90 Prizes and Special Awards 12 Levels of Subsidy, 1966-67 to 1970-71 51 Research Training 91 Cultural Exchanges Doctoral Fe//owships; distribution of 14 Music and Opera Doctoral Fellowships by discipline. 96 Canadian Commission for Unesco 21 Theatre 54 Research Work 100 Stanley House Leave Fellowships; distribution of Leave 27 Dance Fellowships by discipline; Research Finances Grants; distribution of Research Grants 102 Introduction 30 Visual Arts, Film and Photography by disciph’ne; list of Leave Fellowships, Killam Awards and large Research 105 Financial Statement 39 Writing Grants. Appendix 1 48 Other Grants 78 Research Communication 119 List of Doctoral Fellowships List of grants for publication, confer- ences, and travel to international Appendix 2 meetings. 125 List of Research Grants of less than $5,000 86 Special Grants Support of Learned Societies; Appendix 3 Other Assistance. 135 List of Securities March 31. 1971 Members John G. Prentice (Chairman) Brian Flemming Guy Rocher (Vice-Chairman) John M. Godfrey Ronald Baker Elizabeth A. Lane Jean-Charles Bonenfant Léon Lortie Alex Colville Byron March J. -

Keep on Going Frank & Victor Cicansky

Keep On Going Frank & Victor Cicansky This exhibition features the paintings, sculptures and craft objects of folk artist, Frank Cicansky, in dialogue with the ceramics and sculptural work of his son, internationally renowned artist, Victor Cicansky. The presentation of these artists’ works together offers an opportunity to consider the shared values, creative drives and narratives of memory, place and origin that inform both of their artistic practices. Together these works reflect a sincere and compelling response to place, offering immigrant narratives of first and second generation settler Canadians in southern Saskatchewan, while also exploring the influential connections between our province’s folk art and funk art genres. Frank Cicansky’s work not only reflects his skilled craftsmanship, from his training as a blacksmith and wheelwright in Romania before he immigrated in 1926, but offers narratives of his experiences of settlement in his new country, in the Wood Mountain area south of Moose Jaw. Carvings and wooden sculptures of pioneer life depict horses and wagons of threshing teams he would have worked on and the barns and houses he would have built, while the paintings, including a series titled In the Thirties, highlight the hardships of settling in southern Saskatchewan. Known as a great storyteller, Frank chose to depict these memories visually in paint, while incorporating mixed media and text. He also shared the memories behind each image verbally, having them recorded in audio, which have been transcribed in his voice, in his spoken vernacular, and included on the exhibition labels. In these folk images with incorporated text, we see depictions of farmsteads abandoned during the Depression by desperate families with their belongings piled in a wagon, a dead horse, an empty well and clouds of grasshoppers.