Widespread Panic – NPR by Ann Powers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jason Cale Band Song List Izabella

Jason Cale Band Song list Izabella - Hendrix Heavy (I Want You)-- Beatles Tired of Talking--Robben Ford Get in the Clear-- Original *Tall and Lanky-- Jeff Coffin World of Wonder-- Original *Rock me Right-- Susan Tedeschi Mountain Time-- Joe Bonamassa Tell Me I’m Your Man-- Robben Ford Stranglehold-- Ted Nugent Made a Fool of My Heart --Original Django-- Jeff Beck Walk On-- Original Afro Blue-- Fusion jazz standard Our way back--Original Rugged Road-- Robben Ford What ya Say--Original Last Night-- Tab Benoit New Orleans Ladies--Louisiana Lareaux Keep Movin-- Marcus King Band A Fool Like You- Original Cissy Strut--- The Meters *What is and What Should Never Be-- Zeppelin The Chicken-- James Brown *Day of the Eagle*-- Robin Trower Freedom-- Hendrix Never Make Your Move Too Soon-- BB King Say One Thing-- Doyle Bramhall Jump In-- Original Couldn’t Stand the Weather-- SRV *My Love Will Never Die-- Willie Dixon Tightrope--SRV *Anyhow-- Tedeschi Trucks Let Love Take Control--Tab Benoit some kind of wonderful--Grand Funk Railroad Problem Child-- Doyle Bramhall Slave to Society-- Original Iko Iko-- Dr. John When I’m Missing You-- Original? The Storm-- Joe Bonamassa *Human Nature-- Michael Jackson Little Wing-- Hendrix I’m Here to Tell Ya-- Original Lenny-- SRV *Stairway to Heaven-- Zeppelin Mississippi Queen-- Mountain Down the Road- Henrik Fleischander That’s messed UP-- My 3 Sons trio Lay There and Hate Me-- Ben Harper Can’t Always Get What ya Want-- Rolling Stones Her Mind is Gone-- Professor Longhair Scapegoat Blues-- Jimmy Herring *Honky Tonk Women-- Rolling Stones All Blues-- Jazz standard Good love Gone Bad-- Original Sweet Melissa-- Allman Bros Empty Arms-- SRV Burn it Down- blues standard Asking Around for You-- Joe Bonamassa Too Sweet for Me-- Tab Benoit Whipping Post-- Allman Bros Gravity-- John Mayer *Rock and Roll-- Zeppelin Come Together-- Beatles Who Did You Think I Was-- John Mayer Over You-- Original Somber-- Original . -

Relix Magazine

RELIX MAGAZINE Relix Magazine is devoted to the best in live music. Originally launched in 1974 to connect the Grateful Dead community, Relix now features a wide spectrum of artists including: Phish, My Morning Jacket, Beck, Jack White, Leon Bridges, Ryan Adams, Tedeschi Trucks Band, Chris Stapleton, Tame Impala, Widespread Panic, Fleet Foxes, Joe Russo’s Almost Dead, Umphrey’s McGee and plenty more. Relix also offers a unique angle on the action with sections such as: Tour Diary, Behind The Scene, Global Beat, Track By Track, On The Verge and My Page as well as extensive reviews of live shows and recorded music. Each of our 8 annual issues covers new and established artists and comes with a free CD and digital downloads. TOTAL READERSHIP: 360,000+ MONTHLY PAGEVIEWS: 1.6 Million+ MONTHLY UNIQUE USERS: 280,000+ EMAIL SUBSCRIBERS: 225,000+ SOCIAL MEDIA FOLLOWERS: 410,000+ RELIX MEDIA GROUP Relix Media Group is a multifaceted, innovative, open-minded and creative resource for the live music scene. We are a passionate mix of writers, photographers, videographers, event coordinators, musicians and industry professionals. Above all, we are music lovers. Our mission is to seek out exciting, innovative performers and foster the live music community by connecting with the people who matter most: the fans. Since our earliest inception, we have opened doors for the sonically curious and sought to represent the voice of the concert community. Relix Media Group Info • relix.com • jambands.com • 3,700,000 total impressions • 375,000 total unique visitors -

Tanner Strickland Song List

Tanner Strickland Song List: 46 Days- Phish AC/DC Bag- Phish Alaska- Phish Amen Omen- Ben Harper Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way- Waylon Jennings Atlantic City- Bruce Springsteen Banana Pancakes- Jack Johnson Better Together- Jack Johnson Black Balloon- Goo Goo Dolls Blue Sky- The Allman Brothers Band Broke Down Palace- The Grateful Dead Brown Eyed Woman- The Grateful Dead Bubbly Toes- Jack Johnson Casey Jones- The Grateful Dead Catfish John- The Grateful Dead Daughters- John Mayer Deal- The Grateful Dead Dinosaur- Hank Williams, Jr. Dirt- Phish Flake- Jack Johnson Fire On The Mountain- The Grateful Dead Free- The Zac Brown Band Get It While You Can- Infamous Stringdusters Get Up Sex Machine- James Brown Girl I Wanna Lay You Down- Jack Johnson Going Down The Road Feeling Bad- Woody Guthrie Grace Is Gone- The Dave Matthews Band Hard To Handle- The Black Crowes Hold My Hand- Hootie And The Blowfish If It Takes A Lifetime- Jason Isbell I Know You Rider- The Grateful Dead I’m Goin’ Home- Hootie And The Blowfish I’m On Fire- Bruce Springsteen In Color- Jamey Johnson Into The Mystic- Van Morrison Jimi Thing- The Dave Matthews Band Johnny B. Goode- Chuck Berry Julius- Phish Kryptonite- 3 Doors Down Last Train To Clarksville- The Monkeys Lawyers, Guns And Money- Warren Zevon Let Her Cry- Hootie And The Blowfish Man On The Side- John Mayer Melissa- The Allman Brothers Band Midnight Special- Creedence Clearwater Revival Mike’s Song- Phish My Girl- The Temptations Morning Dew- The Grateful Dead Mr. Charlie- The Grateful Dead Ophelia- The Band Picking -

Dominion Energy Riverrock Announces Full 2017 Music Lineup

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release January 24, 2017 Contact: Pete Woody (804) 285-9495 x237 Dominion Riverrock announces full music lineup for 2017 festival Hard Working Americans and The SteelDrivers to headline RICHMOND, VA – Dominion Riverrock announced today the full list of music acts performing at this year’s festival. On Friday, May 19th, The SteelDrivers will take the stage at 8:30 p.m. On Saturday, May 20th, Hard Working Americans will be the headliner, taking the stage at 8:00 p.m. The ninth annual outdoor sports and music festival will be held on Brown’s Island and Historic Tredegar in Richmond, Virginia, May 19-21, 2017. All concerts are free and open to the public. Touring in support of their most recent album ‘Rest In Chaos,’ the follow up to their critically acclaimed self- titled debut in 2014, Hard Working Americans offers a sound invoking the past, present, and future of rock’n’roll music. The group combines the talents of Todd Snider, Widespread Panic’s Dave Schools and Duane Trucks, Chris Robinson Brotherhood’s Neal Casal, Great American Taxi’s Chad Staehly, and Jesse Aycock to form a unique blues and southern rock sound and stage experience. The SteelDrivers, winner of the 2016 Grammy Award for Best Bluegrass Album, are a group of seasoned and distinguished veterans who blend their bluegrass roots with country, soul, and other contemporary influences. The result is a hybrid sound described as ‘new music with old feeling’ that was born in Nashville and has been embraced across the country. (more) Dominion Riverrock Music Lineup Friday, May 19 Time Band 6:00 – 7:00 p.m. -

Black Sabbath the Complete Guide

Black Sabbath The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 17 May 2010 12:17:46 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Black Sabbath 1 The members 23 List of Black Sabbath band members 23 Vinny Appice 29 Don Arden 32 Bev Bevan 37 Mike Bordin 39 Jo Burt 43 Geezer Butler 44 Terry Chimes 47 Gordon Copley 49 Bob Daisley 50 Ronnie James Dio 54 Jeff Fenholt 59 Ian Gillan 62 Ray Gillen 70 Glenn Hughes 72 Tony Iommi 78 Tony Martin 87 Neil Murray 90 Geoff Nicholls 97 Ozzy Osbourne 99 Cozy Powell 111 Bobby Rondinelli 118 Eric Singer 120 Dave Spitz 124 Adam Wakeman 125 Dave Walker 127 Bill Ward 132 Related bands 135 Heaven & Hell 135 Mythology 140 Discography 141 Black Sabbath discography 141 Studio albums 149 Black Sabbath 149 Paranoid 153 Master of Reality 157 Black Sabbath Vol. 4 162 Sabbath Bloody Sabbath 167 Sabotage 171 Technical Ecstasy 175 Never Say Die! 178 Heaven and Hell 181 Mob Rules 186 Born Again 190 Seventh Star 194 The Eternal Idol 197 Headless Cross 200 Tyr 203 Dehumanizer 206 Cross Purposes 210 Forbidden 212 Live Albums 214 Live Evil 214 Cross Purposes Live 218 Reunion 220 Past Lives 223 Live at Hammersmith Odeon 225 Compilations and re-releases 227 We Sold Our Soul for Rock 'n' Roll 227 The Sabbath Stones 230 Symptom of the Universe: The Original Black Sabbath 1970–1978 232 Black Box: The Complete Original Black Sabbath 235 Greatest Hits 1970–1978 237 Black Sabbath: The Dio Years 239 The Rules of Hell 243 Other related albums 245 Live at Last 245 The Sabbath Collection 247 The Ozzy Osbourne Years 249 Nativity in Black 251 Under Wheels of Confusion 254 In These Black Days 256 The Best of Black Sabbath 258 Club Sonderauflage 262 Songs 263 Black Sabbath 263 Changes 265 Children of the Grave 267 Die Young 270 Dirty Women 272 Disturbing the Priest 273 Electric Funeral 274 Evil Woman 275 Fairies Wear Boots 276 Hand of Doom 277 Heaven and Hell 278 Into the Void 280 Iron Man 282 The Mob Rules 284 N. -

April 2019 Newsletter.Pub

Newsletter Date Volume 7, Issue 4 PARK Roanoke’s Newsletter© www.PARKRoanoke.com April 2019 How to Navigate In a Traffic Circle or Roundabout Don’t be a Clark Griswold and drive in continual circles for hours on end as in the famous European Vacation movie. While we don’t have many of these in the Roanoke area, there are more being built throughout our driving area. Often called traffic circles, roundabouts are designed to make intersections safer and more efficient for drivers while avoiding long waits at a standard traffic light. It’s important to know the rules of the road with roundabouts. There are a few key rules to know when driving in a roundabout: 1. The vehicle already in the circle has the right of way 2. Do not Stop in the roundabout 3. Avoid driving next to an oversized vehicle 4. Always watch for pedestrians and pedestrian signal lights. 5. Stay in your lane and give your turn signal when you are ready to exit Prior to entering the roundabout, choose a lane. Once you see a gap in traffic, enter the circle and proceed to your exit. If there is no traffic in the roundabout, you may enter without yielding. To go straight or right, get into the right lane; and, to go straight or left, enter the left lane. Because large vehicles may need extra room to complete their turn in a roundabout, drivers should remember never to drive next to large vehicles in a roundabout. Roundabouts are designed to accommodate vehicles of all sizes, including emergency vehicles, buses, farm equipment and semitrucks with trailers. -

WIDESPREAD PANIC Street Dogs

WIDESPREAD PANIC Street Dogs Widespread Panic has been together going on 30 years. Formed by original members vocalist/guitarist John “JB” Bell, bassist Dave Schools and late guitarist Michael Houser, who lived together in a suburban house in Athens, GA, where they met as students not far from the University of Georgia campus, later to be joined by drummer Todd Nance. Shortly after that, the band’s line-up was solidified with the addition of percussionist Domingo “Sunny” Ortiz and keyboard player John “JoJo” Hermann. Formed in the tradition of the great southern guitar blues bands, with an improvisatory ethos, Widespread Panic continue to explore a sound all its own on the band’s 12th album, Street Dogs, their first studio effort since 2010’s Dirty Side Down. When asked to describe Street Dogs, Widespread Panic’s debut album on Vanguard Records, JB references the way Dr. John describes the music scene in New Orleans as “a gumbo of musical influences.” JB cites Van Morrison and George Carlin as influences while Dave (Grateful Dead/Miles Davis), Mike (Emerson Lake and Palmer), Todd (Steely Dan), Sunny (Tito Puente), JoJo (classically trained with a love for Professor Longhair) and Jimmy (Beatles/ Mahavishnu Orchestra) all bring something different to the table. “Above all, after nearly thirty years together, we are arguably each other’s greatest influence,” JB concludes. That eclectic approach includes the funky New Orleans flavor of “Sell Sell,” their cover of The Animals keyboardist Alan Price’s song from the soundtrack of the 1973 Malcolm McDowell film O Lucky Man!, and the playful nod to a missing feline in the gentle prog- rock of “Steven’s Cat,” written and recorded in a single day in the studio. -

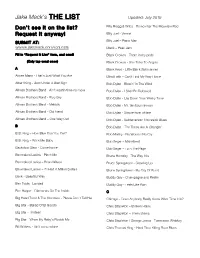

Jake Mack's the LIST

Jake Mack’s THE LIST Updated: July 2019 Don’t see it on the list? Billy Bragg & Wilco - Remember The Mountain Bed Request it anyway! Billy Joel - Vienna SUBMIT AT: Billy Joel – Piano Man wwww.jakemack.com/requests Black – Pearl Jam Fill in “Request It Live” form, and send! Black Crowes - Thorn in my pride (Only tap send once) Black Crowes - She Talks To Angels A Black Keys - Little Black Submarines Aimee Mann - That’s Just What You Are Blind Faith – Can’t Find My Way Home Albert King - Born Under A Bad Sign Bob Dylan - Blowin’ in The Wind Allman Brothers Band - Ain’t wastin time no more Bob Dylan - I Shall Be Released Allman Brothers Band - Blue Sky Bob Dylan - Lay Down Your Weary Tune Allman Brothers Band - Melissa Bob Dylan - Mr. tambourine man Allman Brothers Band - Old friend Bob Dylan - Simple twist of fate Allman Brothers Band – One Way Out Bob Dylan - Subterranean Homesick Blues B Bob Dylan – The Times Are A-Changin’ B.B. King – How Blue Can You Get? Bob Marley - No Woman No Cry B.B. King – Rock Me Baby Bob Seger – Mainstreet Backdoor Slam - Come home Bob Seger – Turn The Page Barenaked Ladies - Pinch Me Bruce Hornsby - The Way It Is Barenaked Ladies – Brian Wilson Bruce Springsteen - Growing Up Barenaked Ladies – If I Had A Million Dollars Bruce Springsteen - My City Of Ruins Beck - Beautiful Way Buddy Guy - Champagne and Reefer Ben Folds - Landed Buddy Guy - Feels Like Rain Ben Harper - Diamonds On The Inside C Big Head Todd & The Monsters - Please Don’t Tell Her Chicago - Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is? Big Star - Ballad -

A Q&A with Dave Schools of Hard Working Americans Dave Schools

A Q&A with Dave Schools of Hard Working Americans Dave Schools is best known as the bassist for legendary Southern jam band Widespread Panic. But this wailer is no one-trick pony: the Richmond, Virginia, native is also an accomplished producer and a member of the new folk-hippy supergroup Hard Working Americans, which is helmed by Todd Snider. We spoke with Schools recently about producing the group’s debut album and playing bass for this wily group of miscreants. What was your initial reaction to the project when you were first approached about it? An emphatic yes, I said I’d love to do it. Anytime I can get a chance to work with Todd, I’ll take it. He’s such a great, positive, entertaining, and special person. Whether it’s just playing bass behind his music or talking about stuff or a project like this, the answer is yes. So this wasn’t the first time you’d worked with him? It’s the first time in the studio, I think. Todd and his band The Nervous Wrecks opened a lot of shows for [Widespread] Panic sometime back in the mid-’90s, and that’s how we kind of got to know each other. And then we reconnected in Nashville when Panic was touring with the Allman Brothers, celebrating their 40th anniversary. I hadn’t seen Todd in a while. He never fell off the radar or anything personally, but we reconnected and last fall he calls out of the blue and says, “I’m playing a gig at the Napa Opera House, do you want to play with me?” And I’m like “sure,” so we did. -

This Is a Great Band, and I Had a Great Time” Bob Weir, Grateful Dead Founding Member (Guitar/Vocalist)

“This is a great band, and I had a great time” Bob Weir, Grateful Dead founding member (guitar/vocalist) “Inspired and accomplished musical discourse at such a deep and serious level: I had no problem at all believing that this was what the Grateful Dead sounded like 40 years ago.” David Gans, Grateful Dead Hour “I've always been impressed by DSO, but the other night I thought they'd taken it to a new level. It was some of the best Grateful Dead music I've heard in the past 20 years, and that covers some ground. Somehow, Jeff Mattson manages to play Jerry's parts perfectly in the spirit, but without any sense of being imitative. And boy, does the band pick up on this energy. Big fun!” Dennis McNally, Grateful Dead publicist & biographer 1980 – 1995; Author “A Long Strange Trip: The History of the Grateful Dead” “As one who is classically trained, I actually always thought that DSO was very cool, treating Grateful Dead music as repertoire- much as I've tried to do in my various bands.” Phil Lesh, Grateful Dead founding member (bass/vocals) “Playing with Dark Star Orchestra is something that feels just exactly like it felt when I was playing with the Grateful Dead.” Donna Jean Godchaux, Grateful Dead vocalist, frequent DSO guest “There are moments where I can close my eyes and go back 30 years and have it be every bit as rewarding and satisfying. Dark Star is an amazingly legitimate representation of the Dead.” Dan Healy, Grateful Dead sound engineer 1966 -1994 “Thank you for a real good time.” Jon Fishman, Phish drummer after sitting in with DSO “The Dark Star Orchestra re-creates Grateful Dead shows with a flashback-inducing meticulousness.” The New Yorker “...recreates the Dead concert experience with uncanny verisimilitude. -

Terence Higgins Drummer Percussionist

TERENCE HIGGINS DRUMMER PERCUSSIONIST BIO New Orleans is known for its great music and culture, and it is also known for spawning some of greatest In The Bywater is named after the neighborhood in which the CD was recorded, one of the most historic drummers in the world. Every serious drummer has been influenced by New Orleans style drumming at in New Orleans. Just down the Mississippi River from the French Quarter, Bywater's colorful, diverse some point in there development. With a unique blend of slinky street beats, New Orleans funk, R&B, history seeps through into the sounds contained on the disc. But with that history comes a marked Zydeco, blues, traditional jazz, and swing, gives New Orleans Drummers that thang!!!.....But don't get it modern slant full of synthetic sounds and forward-thinking musical interplay. Higgins is joined by many of twisted, "New Orleans style of drumming is not method book friendly, it’s all about the feel of it, it’s a his NOLA compatriots here, including sibling keyboard and sax players (Andy and Scott) with the feeling thing and its part of the fabric of New Orleans". impossibly Cajun surname of Bourgeois. Also featured on the album are DDBB guitar craftsman Jamie McLean, trombonist Sammy Williams, bassist Calvin Turner (Jason Crosby, Marc Broussard), and noted Terence was born in New Orleans in 1970 and was raised in the suburb of old Algiers. He was introduced funk guitarist Renard Poche. Together they display the stuff that makes New Orleans music not only to the drums at a very young age by his great grandfather and he has been playing ever since. -

Fact Sheet 2016 2016 Marks Widespread Panic's

Fact Sheet 2016 th ☻ 2016 marks Widespread Panic’s 30 Anniversary th ☻ In celebration of the band’s 25 Anniversary, Widespread Panic took part in the first- ever joint South By Southwest Music Conference showcase and Austin City Limits th television program taping on March 17PP PP 2011PPPPP. “We’ve had Widespread Panic on ACL twice, but we wanted to do something special with them for their 25th anniversary," said ACL Series Executive Producer Terry Lickona. The show aired in Fall 2011. ☻Widespread Panic has been featured on ABC Good Morning America, CBS Sunday Morning, CNN’s Showbiz Today, and has performed on Late Night with Conan O’Brien, Late Show with David Letterman, The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, Austin City Limits, Late Night with Jimmy Fallon and A&E Breakfast with the Arts. ☻2008: Inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame. ☻ Widespread Panic has UUUUheadlinedUUUU most major US festivals, including Bonnaroo (2002-2 days, 2003, 2005-2 days, 2007 and 2008, 2011), Lockn’ Music Festival, Counterpoint Music Festival, Summer Camp, Lollapalooza, 10,000 Lakes, Austin City Limits, Jazz Aspen, Mile High Festival, The Forecastle Festival, Rothbury Festival, All Good Music Festival, Outside Lands Music Festival, Phases of the Moon, Gathering of the Vibes, Vegoose and The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. ☻Widespread Panic has remained in Pollstar’s Top 50 Tours of the Year for the past decade. ☻ In 2003, Widespread Panic sold out 2 nights at New York’s Madison Square Garden and in 2005 sold out 3 nights at the prestigious Radio City Music Hall in NYC.