T He History of the 1911 Pistol the Model 1911 .45 Automatic Pistol Is the World's Most Respected Handgun, and Has Been

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gordon V. Sig Sauer, Inc

Case 4:19-cv-00585 Document 1 Filed on 02/20/19 in TXSD Page 1 of 31 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION DANTÉ GORDON, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, CASE NO. _____________ Plaintiff, v. CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT SIG SAUER, INC., JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Defendant. PLAINTIFF’S ORIGINAL COMPLAINT Plaintiff Danté Gordon, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated as set forth herein, alleges as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. This is a class action brought by gun owners against Defendant SIG SAUER, Inc. (“SIG” or “SIG SAUER”) for manufacturing, distributing, and selling SIG P320-brand semi- automatic pistols that, due to a defect, can inadvertently discharge a round of ammunition if dropped on the ground (a “drop fire”). SIG repeatedly misrepresented and warranted that the P320 pistols were “drop safe,” “won’t fire unless you want [them] to,” and are “originally manufactured free of defects in material, workmanship and mechanical function.” SIG’s original design and manufacture of the P320 pistol rendered the weapon unreasonably dangerous for its intended uses. 2. The P320 is a popular and commercially successful pistol. It is used by law enforcement agencies all over the country, and owned by hundreds of thousands of civilians. In Case 4:19-cv-00585 Document 1 Filed on 02/20/19 in TXSD Page 2 of 31 2016, the U.S. Army selected the SIG P320 to replace the M9 service pistol as the standard-issue sidearm of U.S. military servicemembers. -

The Gunsite 250 Defensive Pistol Class

Here, Jeremy takes part in a final day “Man-On-Man” shoot- off. This kind of pressure shows how well (or not) you operate under stress. Coming Home At SHift’S end Good teachers like to get “hands-on” when teaching. NsITE Here, teacher ThE Gu Sheriff Ken Campbell, a Gunsite adjunct sIvE instructor, hones EfEN a student’s 250 D form on the roll-over prone at 25 yards. Ass stol Cl uGh PI Jeremy D. Cl O cademy and semi-annual qualification simply aren’t enough training and practice for you to develop the skills required to survive a shoot- ing. In real-world shootings cops hit their in- tended target somewhere around 20 percent of the time; that’s four misses for every five rounds fired. That’s also four little lawsuits Afinding some target you didn’t intend, or four rounds worth of time during which the bad guy is shooting at you — and maybe not missing. Consider also pistol bullets are lousy stoppers. While most of us carry hollow points, only 50 percent of those ac- tually expand according to the FBI. But self-defense isn’t a math problem, it’s a time problem, and whoever gets rounds on-target first, lives. 44 WWW.AMERICANCOPMAGAZINE.COM • MAY/JUNE 2011 Room clearing drills are some- In the “Donga” outdoor simulator at Gunsite, students thing we never get enough of “clear” a trail of bad guys, learning how to shoot, in our regular police training, move, be accurate and monitor distance and threats. unless you’re on a SWAT team. -

List of Guns Covered by C&R Permit

SEC. II: Firearms Classified As Curios Or Relics Under 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44 The Bureau has determined that the following firearms are curios or relics as defined in 27 CFR 178.11 because they fall within one of the categories specified in the regulations. Such determination merely classifies the firearms as curios or relics and thereby authorizes licensed collectors to acquire, hold, or dispose of them as curios or relics subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44 and the regulations in 27 CFR Part 178. They are still "firearms" as defined in 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44. Alkartasuna, semiautomatic pistol, caliber .32. All Original military bolt action and semiautomatic rifles mfd. between 1899 and 1946. All properly marked and identified semiautomatic pistols and revolvers used by, or mfd. for, any military organization prior to 1946. All shotguns, properly marked and identified as mfd. for any military organization prior to 1946 and in their original military configuration only. Argentine D.G.F.M. (FMAP) System Colt Model 1927 pistols, marked "Ejercito Argentino" bearing S/Ns less than 24501. Argentine D.G.F.M. - (F.M.A.P.) System Colt model 1927, cal. 11.25mm commercial variations. Armand Gevage, semiautomatic pistols, .32ACP cal. as mfd. in Belgium prior to World War II. Astra, M 800 Condor model, pistol, caliber 9mm parabellum. Astra, model 1921 (400) semiautomatic pistols having slides marked Esperanzo Y Unceta. Astra, model 400 pistol, German Army Contract, caliber 9mm Bergmann-Bayard, S/N range 97351-98850. Astra, model 400 semiautomatic pistol, cal. -

American N Ational Standard

SAAMI Z299.5-2016 Voluntary Industry Performance Standards Criteria for Evaluation of New Firearms Designs Under Conditions of Abusive Mishandling for the Use of Commercial Manufacturers American National Standard Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute, Inc. 11 Mile Hill Road, Newtown, Connecticut 06470-2359 SAAMI Z299.5-2016 Voluntary Industry Performance Standards Criteria for Evaluation of New Firearms Designs Under Conditions of Abusive Mishandling for the Use of Commercial Manufacturers Sponsor Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute, Inc. Members Beretta USA Corporation Marlin Firearms Company Broadsword Group LLC North American Arms, Inc. Browning Arms Company O.F. Mossberg & Sons, Inc. CCI/Speer Ammunition Olin Corporation/Winchester Division Colt’s Manufacturing Company LLC Remington Arms Company, LLC COR-BON/Glaser LLC Savage Arms, Inc. Federal Cartridge Company SIG SAUER, Inc. Fiocchi of America, Inc. Smith & Wesson Holding Corp. Glock St. Marks Powder, Inc. Hodgdon Powder Company Sturm, Ruger & Co., Inc. Hornady Manufacturing Company Taurus Holdings, Inc. Kahr Arms Weatherby, Inc. Associate Members: New River Energetics, LLC Nosler, Inc. Ruag Ammotech USA, Inc. Supporting Members: Advanced Tactical Armament Concepts, LLC Barnes Bullets, LLC Black Hills Ammunition, Inc. Doubletap Ammunition, Inc. Kent Cartridge, America Knight Rifles MAC Ammo One Shot, Inc. Southern Ballistic Research, LLC d/b/a SBR War Sport Industries, LLC Approved March 14, 2016 Abstract This Standard provides procedures for evaluating new firearms designs and applies to rifle, shotguns, pistols and revolvers. In the interest of safety these tests are structured to demonstrate to the designer of new firearms that the product will resist abusive mishandling. These procedures are specifically understood not to apply to muzzle loading and black powder firearms of any type. -

Curios Or Relics List — Update January 2008 Through June 2014 Section II — Firearms Classified As Curios Or Relics, Still Subject to the Provisions of 18 U.S.C

Curios or Relics List — Update January 2008 through June 2014 Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. • Browning, .22 caliber, semiautomatic rifles, Grade III, mfd. by Fabrique Nationale in Belgium. • Browning Arms Company, “Renaissance” engraved FN Hi Power pistols, caliber 9mm, manufactured from 1954 to 1976. • Browning FN, “Renaissance” engraved semiautomatic pistols, caliber .25. • Browning FN, “Renaissance” Model 10\71 engraved semiautomatic pistols, caliber .380. • Colt, Model Lawman Mark III Revolvers, .357 Magnum, serial number J42429. • Colt, Model U, experimental prototype pistol, .22 caliber semiautomatic, S/N U870001. • Colt, Model U, experimental prototype pistol, .22 caliber semiautomatic, S/N U870004. • Firepower International, Ltd., Gustloff Volkssturmgewehr, caliber 7.92x33, S/N 2. • Firepower International, Ltd., Gustloff Volkssturmgewehr, caliber 7.92x33, S/N 6. • Johnson, Model 1941 semiautomatic rifles, .30 caliber, all serial numbers, with the collective markings, “CAL. 30-06 SEMI-AUTO, JOHNSON AUTOMATICS, MODEL 1941, MADE IN PROVIDENCE. R.I., U.S.A., and Cranston Arms Co.” —the latter enclosed in a triangle on the receiver. • Polish, Model P64 pistols, 9 x 18mm Makarov caliber, all serial numbers. • Springfield Armory, M1 Garand semiautomatic rifle, .30 caliber, S/N 2502800. • Walther, Model P38 semiautomatic pistols, bearing the Norwegian Army Ordnance crest on the slide, 9mm Luger caliber, S/N range 369001-370000. • Walther, post World War II production Model P38- and P1-type semiautomatic pistols made for or issued to a military force, police agency, or other government agency or entity. • Winchester, Model 1894, caliber .30WCF, S/N 399704, with 16-inch barrel. -

Firearms Production in the United States with Firearms Import and Export Data

INDUSTRY INTELLIGENCE REPORTS Helping Our Members Make Informed Decisions FIREARMS PRODUCTION IN THE UNITED STATES WITH FIREARMS IMPORT AND EXPORT DATA roviding a comprehensive overview of firearms KEY FINDINGS production trends spanning a period of 25 years, this • The average annual production of firearms Preport is based primarily on the data sourced from the in the U.S. was 5,278,368 for the last Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives’ (ATF’s) quarter century. Annual Firearms Manufacturing and Export Reports (AFMER). • Total firearm production reported in the Every effort has been made to provide accurate and updated 2017 AFMER was 7,901,218 – a decrease of 25.5% over 2016 reported figures. information so the reader may keep this edition as a reliable • Long guns totaled 3,489,295 and resource for trend information. Production data is a leading accounted for 44.2% of total U.S. firearms indicator of industry performance; this is especially true when production. Of that, rifles totaled 2,821,945 combined with other valuable sources of information. (80.9% of long gun production) and shotguns totaled 667,350 (19.1%). This edition includes manufacturing trends for ammunition * See back for all Key Findings as sourced from Census Bureau’s Economic Census, which is conducted once every five years. The Annual Survey of Manufacturers (ASM) is used for all years that fall between those fifth-year economic census reports. Import and export statistics for firearms compiled from the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) are presented in conjunction with the AFMER numbers to provide a more accurate picture of the historical production that has been made available to the U.S. -

Modern Technique of the Pistol by Greg Boyce Morrison Jeff Cooper, Editorial Advisor

The Modern Technique of the Pistol by Greg Boyce Morrison Jeff Cooper, Editorial Advisor reviewed by John M. Buol Jr. Jack Weaver was interviewed by American Handgunner magazine (May/June 2008) about how he created the Weaver Stance and the history of practical shooting. These developments led to what is known as the The Modern Technique of the Pistol. Greg Morrison, under advisement from Jeff Cooper, wrote a book of the same name that stands as the definitive text of the subject. Overview This 1991 effort codifies the then-current doctrine of defensive pistol as taught by the American Pistol Institute (API), now under different management and called Gunsite Ranch. The forward begins with "The Evolution of the Modern Technique", as described by co-creator and chief proponent, Jeff Cooper. Dissatisfied with handgun technique of of the time, Cooper attempted to improve handgun technique by helping put forth an "Advanced Combat Pistol Course" just after World War II. Upon separation from service, and free from bureaucratic restriction, he formed several shooting clubs and ran a number of different competitive venues with the help of several like-minded marksmen, mostly from the civilian sector. Over the course of time, consistent winners and their technique began to surface in these varying, freestyle matches. These events would lead to the creation of the International Practical Shooting Confederation and lay the foundation for a number of practical shooting disciplines. The best, most consistent techniques of the day were codified into the "Modern Technique of the Pistol." and Cooper founded API to teach it. The Modern Technique consists of three components, or the "Combat Triad": 1.Marksmanship 2.Gun Handling 3.Mind-Set The book begins with Mind-Set, which includes the "thinking side" of the triad, ranging from safety procedures, combat mind-set, and basic, individual tactics. -

Small Arms for Urban Combat

Small Arms for Urban Combat This page intentionally left blank Small Arms for Urban Combat A Review of Modern Handguns, Submachine Guns, Personal Defense Weapons, Carbines, Assault Rifles, Sniper Rifles, Anti-Materiel Rifles, Machine Guns, Combat Shotguns, Grenade Launchers and Other Weapons Systems RUSSELL C. TILSTRA McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Tilstra, Russell C., ¡968– Small arms for urban combat : a review of modern handguns, submachine guns, personal defense weapons, carbines, assault rifles, sniper rifles, anti-materiel rifles, machine guns, combat shotguns, grenade launchers and other weapons systems / Russell C. Tilstra. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6523-1 softcover : acid free paper 1. Firearms. 2. Urban warfare—Equipment and supplies. I. Title. UD380.T55 2012 623.4'4—dc23 2011046889 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2012 Russell C. Tilstra. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Front cover design by David K. Landis (Shake It Loose Graphics) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com To my wife and children for their love and support. Thanks for putting up with me. This page intentionally left blank Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations . viii Preface . 1 Introduction . 3 1. Handguns . 9 2. Submachine Guns . 33 3. -

Catalogue Browning 2009

2009 Browning | Hunting & Shooting © Robert Giede Browning: the most sensitive of passions Since 1897, the date of birth of the first Browning gun, millions, even tens of millions, of shotguns and rifles for hunting or target-shooting have created and signed by Browning. BAR Zenith Prestige Wood The inventor of the semi-automatic shotgun, the semi-automatic rifle and, the most recent innovation, an over-and-under gun with the lowest action frame and fastest firing system on the market has left its mark on the history of gun-making with a profu- sion of models, all different, but with one thing in common – their reliability and their unequalled levels of performance. Every day throughout the world, Browning guns, old and new, continue to give their owners great pleasure. Browning guns have a much deserved reputation for quality and reliability which gives their owners complete confidence in our products. John Moses Browning was dedicated to excellence, quality and reliability and this philosophy contin- ues throughout Browning today and going forward into the future. Browning guns have an unrivalled reputation for quality and reliability, a tradition which Browning continues to build on. We are mightly proud of our history and work hard to ensure that those who choose Browning benefit from our years of experience, skill and dedication to quality. Browning, Simply - The Best there is. X-Bolt Hunter 2 Contents | Browning 2009 Introduction 2-11 Hunting Firearms | big game 50-77 Browning: the most sensitive of passions 2 Double Express Rifles -

Christian Sailer: 1

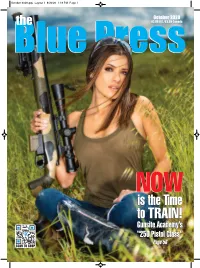

October 2020.qxp_Layout 1 8/20/20 1:18 PM Page 1 October 2020 the $2.99 U.S./$3.99 Canada BlueBlue PressPress NOW is the Time to TRAIN! Gunsite Academy’s “250 Pistol Class” Page 56 SCAN TO SHOP October 2020.qxp_Layout 1 8/20/20 1:18 PM Page 2 2 800-223-4570 • 480-948-8009 • bluepress.com Blue Press October 2020.qxp_Layout 1 8/20/20 1:19 PM Page 3 Which Dillon is Right for YOU? Page 28 Page 24 Page 20 Page 16 Page 12 SquareOur automatic-indexing Deal B The World’sRL 550C Most Versatile Truly theXL state 750 of the art, OurSuper highest-production- 1050 Our RLnewest 1100 reloader progressive reloader Reloader, capable of loading our XL 750 features rate reloader includes a features an innovative designed to load moderate over 160 calibers. automatic indexing, an swager to remove the crimp eccentric bearing drive quantities of common An automatic casefeeder is optional automatic from military primer system that means handgun calibers from available for handgun casefeeder and a separate pockets, and is capable of smoother operation with .32 S&W Long to .45 Colt. calibers. Manual indexing station for an optional reloading all the common less effort, along with an It comes to you from the and an optional magnum powder-level sensor. handgun calibers and upgraded primer pocket factory set up to load powder bar allow you to Available in all popular several popular rifle swager. Loads up to .308 one caliber. load magnum rifle calibers. pistol and rifle calibers. -

ANNUAL SIGHTING in DAY EVENT RUNS from 9:00AM TILL 4:00PM SUNDAY NOVEMBER 8Th

KALAMAZOO ROD & GUN CLUB 7533 N. Sprinkle Rd. Kalamazoo, Michigan 49019 Newsletter October – December 2020 2020 Officers and Board of Directors (all #’s are area code 269 unless otherwise stated) President Tom Fenwick 323-1330 Two Year Directors Jerry Trepanier 366-8281 Vice President Randy Hendrick 716-0140 Scott Tyler 615-8947 Treasurer Caleb Miller (517) 420-1789 Dave Van Lopik 207-4494 Recording Secretary Sonya Terburg 569-2562 Andy Woolf 377-0840 Membership Secretary John Ceglarek 312-8008 One Year Directors John Ceglarek 312-8008 Range Safety Officer Vince Lester 838-6748 Bill Nichols 743-8401 Newsletter Bill Nichols 743-8401 Chris Ronfeldt 492-4021 Mike Tyler 350-6340 KALAMAZOO ROD AND GUN CLUB 7533 N SPRINKLE RD PHONE 269-377-0840 ANNUAL SIGHTING IN DAY EVENT RUNS FROM 9:00AM TILL 4:00PM SUNDAY NOVEMBER 8th. THE TARGETS WILL BE AT 50 & 100 YARDS. TARGETS AND SPOTTERS WILL BE FURNISHED. WE WILL BORE SIGHT GUNS THAT NEED IT. THIS EVENT IS FOR RIFLES, SHOTGUNS, MUZZLELOADERS, PISTOLS AND REVOLVERS. WE DO NOT ALLOW ANY CALIBERS BELOW .223 AT THIS EVENT. THIS EVENT IS NOT FOR TARGET PRACTICE. This is a FREE event OPEN TO THE PUBLIC. SAFETY GLASSES AND HEARING PROTECTION ARE REQUIRED. PUBLIC IS WELCOME. Visit our website: kalamazoorodandgunclub.com Fall Work Day New Member Applications Now Volunteers Needed for November Available On Website Sighting In Day Most readers of this Newsletter know that because of the governor’s If you know anyone interested in As you saw on the introduction page lockdown earlier this year, our joining our Club, please direct of this Edition, the Club will once annual Spring Work Day was them to our website, where the again be hosting its annual Sighting- cancelled. -

Ruger M77 Ruger

Krebs Custom AK 7.62x39 & More! $4.95$4.95 OUTSIDEOUTSIDE U.S.U.S. $7.95$7.95 NOVEMBERNOVEMBER 20112011 GUNSITE SCOUT RUGER M77 .308.308 WIN SxS ELEGANCE FAUSTI 28 GAUGE RIMFIRE EXTRA • BROWNING 1911-22 • COLT 1911-22 HANDLOADING THE.338 WIN PETITE DEFENSE S&W BODYGUARDS .380 ACP & .38 SPECIAL SERVING SOLDIER’S CHRISTMAS GIFT GUIDE www.gunsmagazine.com 2 WWW.GUNSMAGAZINE.COM • NOVEMBER 2011 Untitled-2 1 7/13/11 2:08:32 PM WWW.GUNSMAGAZINE.COM 3 Untitled-2 1 7/13/11 2:08:32 PM NOVEMBER 2011 Vol. 57, Number 11, 671st Issue COLUMNS CROSSFIRE 6 LEttERS tO thE EdItOR RANGING SHOTS™ ENtER 8 CLINt SMIth 84 1 2 HANDLOADING tO WIN! JOhN BARSNESS KREBS CUSTOM 1 6 HANDGUNS MASSAd AyOOB AK-103K BUILT 1 8 RIMFIRES 28 HOLt BOdINSON ON A RUSSIAN MONTANA MUSINGS SAIGA CARBINE! 2 4 MIkE “dUkE” VENtURINO UP ON ARs 2 6 GLEN ZEdIkER RIFLEMAN Dave 2 8 ANdERSON KNIVES A 68 P t COVERt VIEWS, NEWS & REVIEWS DEPARTMENTS 7 0 RIGhtS WAtCh: David COdREA SURPLUS LOCKER™ Hol30 t BOdINSON ODD ANGRY SHOT .310 MARtINI CAdEt 86 JOhN CONNOR 34 OUT OF THE BOX™ 9 0 CAMPFIRE TALES miKE CUMPSTON JOhN TaffIN 24 S&W BOdyGUARdS SEMI-AUtO ANd revolver QUESTIONS & ANSWERS 38 JEff JOhN QUARTERMASTER Fea78 tURING GUNS ALLStARS! THIS MONTH: GUNS Magazine (ISSN 1044-6257) is published • JEff JOhN monthly by Publishers’ Development Corpora- • MIkE CUMPStON tion, 12345 World Trade Drive, San Diego, CA 92128. Periodicals Postage Paid at San Diego, CA and at additional mail- ing offices.