IGA 8/E Chapter 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Screening of the Second-Site Suppressor Mutations of The

Int. J. Cancer: 121, 559–566 (2007) ' 2007 Wiley-Liss, Inc. The screening of the second-site suppressor mutations of the common p53 mutants Kazunori Otsuka, Shunsuke Kato, Yuichi Kakudo, Satsuki Mashiko, Hiroyuki Shibata and Chikashi Ishioka* Department of Clinical Oncology, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, and Tohoku University Hospital, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan Second-site suppressor (SSS) mutations in p53 found by random mutation library covers more than 95% of tumor-derived missense mutagenesis have shown to restore the inactivated function of mutations as well as previously unreported missense mutations. some tumor-derived p53. To screen novel SSS mutations against We have shown the interrelation among the p53 structure, the common mutant p53s, intragenic second-site (SS) mutations were function and tumor-derived mutations. We have also observed that introduced into mutant p53 cDNA in a comprehensive manner by the missense mutation library was useful to isolate a number of using a p53 missense mutation library. The resulting mutant p53s 16,17 with background and SS mutations were assayed for their ability temperature sensitive p53 mutants and super apoptotic p53s. to restore the p53 transactivation function in both yeast and Previous studies have shown that there are second-site (SS) mis- human cell systems. We identified 12 novel SSS mutations includ- sense mutations that recover the inactivated function of tumor- ing H178Y against a common mutation G245S. Surprisingly, the derived mutations, so-called intragenic second-site suppressor G245S phenotype is rescued when coexpressed with p53 bearing (SSS) mutations.18–23 Analysis of the molecular background of the H178Y mutation. -

Antibiotic Resistance by High-Level Intrinsic Suppression of a Frameshift Mutation in an Essential Gene

Antibiotic resistance by high-level intrinsic suppression of a frameshift mutation in an essential gene Douglas L. Husebya, Gerrit Brandisa, Lisa Praski Alzrigata, and Diarmaid Hughesa,1 aDepartment of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology, Biomedical Center, Uppsala University, Uppsala SE-751 23, Sweden Edited by Sankar Adhya, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, and approved January 4, 2020 (received for review November 5, 2019) A fundamental feature of life is that ribosomes read the genetic (unlikely if the DNA sequence analysis was done properly), that the code in messenger RNA (mRNA) as triplets of nucleotides in a mutants carry frameshift suppressor mutations (15–17), or that the single reading frame. Mutations that shift the reading frame gen- mRNA contains sequence elements that promote a high level of ri- erally cause gene inactivation and in essential genes cause loss of bosomal shifting into the correct reading frame to support cell viability viability. Here we report and characterize a +1-nt frameshift mutation, (10). Interest in understanding these mutations goes beyond Mtb and centrally located in rpoB, an essential gene encoding the beta-subunit concerns more generally the potential for rescue of mutants that ac- of RNA polymerase. Mutant Escherichia coli carrying this mutation are quire a frameshift mutation in any essential gene. We addressed this viable and highly resistant to rifampicin. Genetic and proteomic exper- by isolating a mutant of Escherichia coli carrying a frameshift mutation iments reveal a very high rate (5%) of spontaneous frameshift suppres- in rpoB and experimentally dissecting its genotype and phenotypes. sion occurring on a heptanucleotide sequence downstream of the mutation. -

Genetic Dissection of Developmental Pathways*§ †

Genetic dissection of developmental pathways*§ † Linda S. Huang , Department of Biology, University of Massachusetts-Boston, Boston, MA 02125 USA Paul W. Sternberg, Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Division of Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 USA Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 2. Epistasis analysis ..................................................................................................................... 2 3. Epistasis analysis of switch regulation pathways ............................................................................ 3 3.1. Double mutant construction ............................................................................................. 3 3.2. Interpretation of epistasis ................................................................................................ 5 3.3. The importance of using null alleles .................................................................................. 6 3.4. Use of dominant mutations .............................................................................................. 7 3.5. Complex pathways ........................................................................................................ 7 3.6. Genetic redundancy ....................................................................................................... 9 3.7. Limits of epistasis ...................................................................................................... -

Genetic Suppression* §

Genetic suppression* § Jonathan Hodgkin , Genetics Unit, Department of Biochemistry, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3QU, UK Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................2 2. Intragenic suppression by same site replacement ............................................................................ 2 3. Intragenic suppression by compensatory second site mutation .......................................................... 2 4. Intragenic suppression by altered splicing ..................................................................................... 2 5. Intragenic suppression of dominant mutations by loss-of-function in cis. ............................................2 6. Extragenic suppression — overview ............................................................................................ 3 7. Informational suppression — overview ........................................................................................ 4 8. Nonsense suppression ............................................................................................................... 4 9. Extragenic suppression by modified splicing ................................................................................. 5 10. Suppression by loss of NMD (Nonsense Mediated Decay) ............................................................. 6 11. Extragenic suppression by non-specific physiological effects ......................................................... -

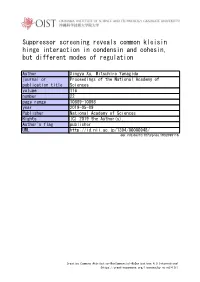

Suppressor Screening Reveals Common Kleisin–Hinge Interaction in Condensin and Cohesin, but Different Modes of Regulation

Suppressor screening reveals common kleisin hinge interaction in condensin and cohesin, but different modes of regulation Author Xingya Xu, Mitsuhiro Yanagida journal or Proceedings of the National Academy of publication title Sciences volume 116 number 22 page range 10889-10898 year 2019-05-09 Publisher National Academy of Sciences Rights (C) 2019 the Author(s). Author's flag publisher URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1394/00000948/ doi: info:doi/10.1073/pnas.1902699116 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/) Suppressor screening reveals common kleisin–hinge interaction in condensin and cohesin, but different modes of regulation Xingya Xua and Mitsuhiro Yanagidaa,1 aG0 Cell Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Onna-son, 904-0495 Okinawa, Japan Contributed by Mitsuhiro Yanagida, April 1, 2019 (sent for review February 15, 2019; reviewed by Kerry Bloom, David M. Glover, and Robert V. Skibbens) Cohesin and condensin play fundamental roles in sister chromatid establishment/dissolution cycle have been demonstrated (7). This cohesion and chromosome segregation, respectively. Both consist kind of approach, if employed systematically using numerous of heterodimeric structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) mutations, can be developed on a much more comprehensive subunits, which possess a head (containing ATPase) and a hinge, scale, and will give us a systematic view of how complex molec- intervened by long coiled coils. Non-SMC subunits (Cnd1, Cnd2, ular assemblies are organized (8). and Cnd3 for condensin; Rad21, Psc3, and Mis4 for cohesin) bind to Condensin and cohesin are two fundamental protein com- the SMC heads. -

The Molecular Basis of Suppression in an Ochre Suppressor Strain Possessing Altered Ribosomes* by T

THE MOLECULAR BASIS OF SUPPRESSION IN AN OCHRE SUPPRESSOR STRAIN POSSESSING ALTERED RIBOSOMES* BY T. KENT GARTNER, EDUARDO ORIAS, JAMES E. LANNAN, JAMES BEESON, AND PARLANE J. REID DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA (SANTA BARBARA) Communicated by Charles Yanofsky, January 30, 1969 Abstract.-Escherichia coli K12 2320(X)-15B has a mutation that results in ochre suppressor activity.1 This mutation concomitantly causes a decreased growth rate in rich medium, an increased sensitivity to streptomycin,l and the production of some altered 30S ribosomes which are differentially sensitive to RNase.2 The results presented below demonstrate that the molecules which cause suppression are tRNA. These observations justify the conclusions that the suppressor mutation did not occur in a structural gene for a ribosomal component, and that the decreased growth rate in rich medium, the increased sensitivity to streptomycin, and the production of altered 30S ribosomes are probably all secondary consequences of the suppressor mutation. Introduction.-Strain 15B is an ochre suppressor mutant which was isolated as a phenotypically lac+ revertant of strain 2320(X).1 Strain 15B is an atypical ochre suppressor mutant because the mutation that causes the suppression also causes the synthesis of some altered 30S ribosomes,2 a decreased growth rate in rich medium, and an increased sensitivity to streptomycin.1 Since the mu- tation that causes ochre suppressor activity in strain 15B also causes the syn- thesis of some altered 30S ribosomes, the ribosomes of strain 15B were tested for suppressor activity. The results of this investigation which are presented below demonstrate, however, that most if not all of the suppressor activity of strain 15B resides in tRNA. -

Fall 1996 ANSWER KEY Exam 1 Q1. a Frameshift Mutation in the Arc Gene Results in Premature Termination of the Encoded Protein at an Amber Codon

Mcbio 316 - Fall 1996 ANSWER KEY Exam 1 Q1. A frameshift mutation in the arc gene results in premature termination of the encoded protein at an amber codon. However, the mutant is not suppressed by an amber suppressor. (5) Explain why. Downstream of the frameshift mutation translation occurs in the wrong reading frame. Thus even if premature termination is prevented by suppression of the "out- of-frame" nonsense codon, translation in the wrong reading frame will produce multiple amino acid changes, resulting in an inactive protein. Note - this question specifically asked about the effect of an amber suppressor on a frameshift mutation, not how amber suppressors work or how frameshift suppressors work. Q2. It is not possible to obtain true revertants of a deletion mutation in a haploid organism. However, it is sometimes possible to obtain second site revertants of a deletion mutation. (5) a. What type of second site reversion event is most likely? [Explain.] The most likely type of reversion event is a bypass suppressor because it completely avoids the need for the gene product. Note - failure to obtain true revertants indicates that the deletion mutation described is not a simple frameshift mutation. Thus, your answer should explain how a large deletion can revert. It is true that in some very rare cases an insertion mutation could compensate for the deletion, but this is less likely than a bypass suppressor. Furthermore, if you suggested that an insertion mutation could compensate, you would need to describe (i) how it would compensate, and (ii) where the insertion of DNA might come from. -

Science Journals

RESEARCH ◥ us to formulate and quantify the general RESEARCH ARTICLE SUMMARY mechanisms of genetic suppression, which has the potential to guide the identification of modifier genes affecting the penetrance of YEAST GENETICS genetic traits, including human disease.▪ Exploring genetic suppression Genetic suppression Wild type interactions on a global scale Jolanda van Leeuwen, Carles Pons, Joseph C. Mellor, Takafumi N. Yamaguchi, Helena Friesen, John Koschwanez, Mojca Mattiazzi Ušaj, Maria Pechlaner, Mehmet Takar, Matej Ušaj,BenjaminVanderSluis,KerryAndrusiak,Pritpal Bansal, Anastasia Baryshnikova, Claire E. Boone, Jessica Cao, Atina Cote, Marinella Gebbia, Gene Horecka, Ira Horecka, Elena Kuzmin, Nicole Legro, Wendy Liang, Natascha van Lieshout, Margaret McNee, Normal fitness Reduced fitness Restored fitness (sick) (healthy) Bryan-Joseph San Luis, Fatemeh Shaeri, Ermira Shuteriqi, Song Sun, Lu Yang, Ji-Young Youn, Michael Yuen, Michael Costanzo, Anne-Claude Gingras, Patrick Aloy, Chris Oostenbrink, Andrew Murray, Todd R. Graham, Chad L. Myers,* Brenda J. Andrews,* Mapping a global suppression network Frederick P. Roth,* Charles Boone* • 1842 Literature curated suppression interactions • 195 Systematically derived INTRODUCTION: Genetic suppression oc- ping and whole-genome sequencing, we also suppression interactions curs when the phenotypic defects caused by isolated an unbiased, experimental set of ~200 - Genetic mapping a mutated gene are rescued by a mutation in spontaneous suppressor mutations that cor- - Whole genome sequencing another gene. rect the fitness defects of deletion or hypomor- on January 22, 2017 These genetic interactions can connect phic mutant alleles. Integrating these results genes that work within the same pathway yielded a global suppression network. Enrichment of suppression gene pairs or biological process, providing new ◥ The majority of suppression in- ON OUR WEBSITE colocal- GO coan- coex- same same 0164 mechanistic insights into cellular teractions identified novel gene-gene ization notation pression pathway complex fold enrich. -

Suppression Mechanisms Reviews Suppression Mechanisms Themes from Variations

Suppression mechanisms Reviews Suppression mechanisms themes from variations Suppressor analysis is a commonly used strategy to identify functional relationships between genes that might not have been revealed through other genetic or biochemical means. Many mechanisms that explain the phenomenon of genetic suppression have been described, but the wide variety of possible mechanisms can present a challenge to defining the relationship between a suppressor and the original gene. This article provides a broad framework for classifying suppression mechanisms and describes a series of genetic tests that can be applied to determine the most likely mechanism of suppression. he analysis of any biological process by classical genetic basis for distinguishing the classes, allowing the investigator Tmethods ultimately requires multiple types of mutant to: (1) pursue the class that best suits their particular interests; selections to identify all the genes involved in that process. (2) identify systematically the relationship between the two One strategy commonly used to identify functionally gene products; and (3) design rationally future suppressor related genes is to begin with a strain that already contains hunts to increase the likelihood of obtaining the desired a mutation affecting the pathway of interest, selecting for classes of mutations. Some practical aspects should be mutations that modify its phenotype. Modifiers that result considered when designing suppressor hunts (Box 1). in a more severe phenotype are termed enhancers, while mutations that restore a more wild-type phenotype despite Intragenic suppression the continued presence of the original mutation are termed The simplest suppression mechanism to conceptualize is suppressors. Historically, suppressors have proven intragenic suppression, where a phenotype caused by a extremely valuable for determining the relationship primary mutation is ameliorated by a second mutation in between two gene products in vivo, even in the absence of the same gene. -

The Red Strain "Ad2, , SU-Ad2, 1"

i/i, A CYTOPLASMIC SUPPRESSOR OF SUPER-SUPPRESSOR IN YEAST B.S. COX Departmentof Genetics. University of Liverpool Received24.ii.65 1.INTRODUCTION IN1963, Hawthorne and Mortimer reported an analysis of some suppressors of auxotrophic requirements in yeast. They found that such suppressors were unspecific in the sense that the suppression effect was not dependent on the function affected by a mutation, but were specific in that not all, only a proportion of the alleles leading to any particular loss of function were suppressible. Manney (1964) has confirmed that about a third of all ultra-violet induced mutants of yeast are suppressible by such suppressors. It appears from the data that separately isolated suppressors are often inherited in- dependently of one another, and that, whenever tested, they have the same specificity. During the course of studies on spontaneous inter-allelic reversions during vegetative growth in yeast, a number of revertants were recovered whose behaviour, on analysis, showed that they were due to genetically controlled suppression of one of the alleles in the diploid. A typical segregation, that of the revertant Q,isshown in table i. The original diploid used in the cross was composed as follows: —a,ad2,, hi8,se1, me2, fr1 — adenine-requiring. ad2, —--— - = red, All markers except adenine requirement and colour segregate 2+: 2— in every tetrad. The adenine requirement, however, segregates 1+: 3— in four tetrads and 0+: 4— in two tetrads. It is possible to distinguish ad2, 1 from ad2, by a complementation test (Woods, 1963). When this is done it is seen that ad2, and ad2, segregate regularly each to two spores in every tetrad. -

Missense Mutations Allow a Sequence-Blind Mutant of Spoiiie to Successfully Translocate Chromosomes During Sporulation

Missense Mutations Allow a Sequence-Blind Mutant of SpoIIIE to Successfully Translocate Chromosomes during Sporulation The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bose, Baundauna, Sydney E. Reed, Marina Besprozvannaya, and Briana M. Burton. 2016. “Missense Mutations Allow a Sequence-Blind Mutant of SpoIIIE to Successfully Translocate Chromosomes during Sporulation.” PLoS ONE 11 (2): e0148365. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0148365. Published Version doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148365 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:25658517 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA RESEARCH ARTICLE Missense Mutations Allow a Sequence-Blind Mutant of SpoIIIE to Successfully Translocate Chromosomes during Sporulation Baundauna Bose¤a, Sydney E. Reed, Marina Besprozvannaya¤b, Briana M. Burton¤c* Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America ¤a Current address: Evelo Biosciences, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America ¤b Current address: Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of California, Davis, Davis, California, United States of America ¤c Current address: Department of Bacteriology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Bose B, Reed SE, Besprozvannaya M, Burton BM (2016) Missense Mutations Allow a SpoIIIE directionally pumps DNA across membranes during Bacillus subtilis sporulation Sequence-Blind Mutant of SpoIIIE to Successfully and vegetative growth. -

ASSEMBLY of the MITOCHONDRIAL MEMBRANE SYSTEM: NUCLEAR SUPPRESSION of a CYTOCHROME B MUTATION in YEAST MITOCHONDRIAL DNA

ASSEMBLY OF THE MITOCHONDRIAL MEMBRANE SYSTEM: NUCLEAR SUPPRESSION OF A CYTOCHROME b MUTATION IN YEAST MITOCHONDRIAL DNA GLORIA CORUZZI AND ALEXANDER TZAGOLOF" Department of Biological Sciences, Columbia University, New York, N. Y. 10027 Manuscript received December 3, 1979 Revised copy received May 5,1980 ABSTRACT In a previous study, a mitochondrial mutant expressing a specific enzymatic deficiency in co-enzyme QH,-cytochrome c reductase was described (TZAGO- LOFF, FOURYand AEAI 1976). Analysis of the mitochondrially translated pro- teins revealed the absence in the mutant of the mitochondrial product corres- ponding to cytochrome b and the presence of a new low molecular weight product. The premature chain-termination mutant was used to obtain sup- pressor mutants with wild-type properties. One such revertant strain was analyzed genetically and biochemically. The revertant was determined to have a second mutation in a nuclear gene that is capable of partially suppressing the original mitochondrial cytochrome b mutation. Genetic data indicate that the nuclear mutation is recessive and is probably in a gene coding far a protein involved in the mitochondrial translation machinery. YEAST mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is known to code for cytochrome b, a well-characterized carrier of co-enzyme QH,-cytochrome c reductase. In a previous study, a mutant of Saccharomyces oerevisiae was shown to have a genetic lesion in the cytochrome b gene (TZAGOLOFF,FOURY and AKAI1976). The mutation (M9-228) was mapped in the cob2 locus and was shown to cause the loss of a wild-type mitochondrial translation product corresponding to the cytochrome b apoprotein. The mutant was of interest because of the appearance of a new low molecular weight mitochondrial product.