Legal Education (Part Ii)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demand Driven Education: Merging Work and Learning to Develop the Human Skills That Matter

DEMAND DRIVEN EDUCATION Demand Driven Education Merging work & learning to develop the human skills that matter By Joe Deegan & Nathan Martin 1 About the Authors Acknowledgements Joe Deegan is a senior program manager with JFF, providing This publication was made possible through generous support research and technical assistance at the intersection of postsecondary from Pearson. education and workforce development. He studies emerging and alternative education models that have the potential to benefit people The foundational research for this report came from interviews from low-income backgrounds and other underrepresented college with experts in higher education. We are enormously grateful to all learners. He also provides program-level coaching to practitioners. of them for sharing their time and insights. In particular, we would Prior to working for JFF, Mr. Deegan managed a postsecondary like to thank Tom Ogletree from General Assembly; Kalonji Martin bridging program that connected out-of-school youth to community from Nepris; Michael Bettersworth from SkillsEngine; Leslie Hirsch college. He has taught English as a foreign language to Slovak middle from City University of New York; Vivian Murinde from the London and high school students as part of the Fulbright English Teaching Legacy Development Corporation; Sumi Ejiri from A New Direction; Assistantship program. Mr. Deegan holds a bachelor’s degree in and Leah Jewell, Kristen DiCerbo, and Steve Besley from Pearson. English literature from King’s College (Pennsylvania) and a master’s degree in public affairs from Indiana University’s School of Public Joe Deegan would also like to thank his JFF colleagues for their and Environmental Affairs. -

University Microfilms International 300 N, ZEEB RD

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.Thc sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing pagc(s) or section, they arc spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed cither blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Marking 200 Years of Legal Education: Traditions of Change, Reasoned Debate, and Finding Differences and Commonalities

MARKING 200 YEARS OF LEGAL EDUCATION: TRADITIONS OF CHANGE, REASONED DEBATE, AND FINDING DIFFERENCES AND COMMONALITIES Martha Minow∗ What is the significance of legal education? “Plato tells us that, of all kinds of knowledge, the knowledge of good laws may do most for the learner. A deep study of the science of law, he adds, may do more than all other writing to give soundness to our judgment and stability to the state.”1 So explained Dean Roscoe Pound of Harvard Law School in 1923,2 and his words resonate nearly a century later. But missing are three other possibilities regarding the value of legal education: To assess, critique, and improve laws and legal institutions; To train those who pursue careers based on legal training, which may mean work as lawyers and judges; leaders of businesses, civic institutions, and political bodies; legal academics; or entre- preneurs, writers, and social critics; and To advance the practice in and study of reasoned arguments used to express and resolve disputes, to identify commonalities and dif- ferences, to build institutions of governance within and between communities, and to model alternatives to violence in the inevi- table differences that people, groups, and nations see and feel with one another. The bicentennial of Harvard Law School prompts this brief explo- ration of the past, present, and future of legal education and scholarship, with what I hope readers will not begrudge is a special focus on one particular law school in Cambridge, Massachusetts. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ∗ Carter Professor of General Jurisprudence; until July 1, 2017, Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor, Harvard Law School. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

The Place of Skills in Legal Education*

THE PLACE OF SKILLS IN LEGAL EDUCATION* 1. SCOPE AND PURPOSE OF THE REPORT. There is as yet little in the way of war or post-war "permanent" change in curriculum which is sufficiently advanced to warrant a sur- vey of actual developments. Yet it may well be that the simpler curricu- lum which has been an effect of reduced staff will not be without its post-war effects. We believe that work with the simpler curriculum has made rather persuasive two conclusions: first, that the basic values we have been seeking by case-law instruction are produced about as well from a smaller body of case-courses as from a larger body of them; and second, that even when classes are small and instruction insofar more individual, we still find difficulty in getting those basic values across, throughout the class, in terms of a resulting reliable and minimum pro- fessional competence. We urge serious attention to the widespread dis- satisfaction which law teachers, individually and at large, have been ex- periencing and expressing in regard to their classes during these war years. We do not believe that this dissatisfaction is adequately ac- counted for by any distraction of students' interest. We believe that it rests on the fact that we have been teaching classes which contain fewer "top" students. We do not believe that the "C" students are either getting materially less instruction-value or turning in materially poorer papers than in pre-war days. What we do believe is that until recently the gratifying performance of our best has floated like a curtain between our eyes and the unpleasant realization of what our "lower half" has not been getting from instruction. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Experience the Future of Legal Education

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Articles & Book Chapters Faculty Scholarship 2014 Experience the Future of Legal Education Lorne Sossin Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Source Publication: Alberta Law Review. Volume 51 Issue 4 (2014), p. 849-870. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Sossin, Lorne. "Experience the Future of Legal Education." Alberta Law Review 51 (2014): 849-870. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. EXPERIENCE THE FUTURE OF LEGAL EDUCATION 849 EXPERIENCE THE FUTURE OF LEGAL EDUCATION 849 EXPERIENCE THE FUTURE OF LEGAL EDUCATION LORNE SOSSIN' This articleexamines the shift towards experiential Cet article porte sur le virage de la formation legal education and its implications.While others have juridiquepar expirience et ses implications.Alors que focused on experiential education as a means of d'autres ont cible I'dducation expirientielle comme training better lawyers, the author advances the moyen de former de meilleurs avocats, I'auteurfait argument for experiential education because it is valoir le bien-fonde de cet apprentissageparce qu'il rooted in substantive problem-solving, access to est ancrd dans la rdsolution de problimes de fond, justice, engagement with communities, and greater I'accis b Ia justice, la mobilisation communautaireet opportunitiesfor reflective and criticalthinking about de meilleures possibilitis de riflexion et de pense law andjustice. -

Changing Legal Pedagogy by Will Pasley (UC Hastings NLG Graduate) and Traci Yoder (NLG Director of Research and Education)

Changing Legal Pedagogy By Will Pasley (UC Hastings NLG Graduate) and Traci Yoder (NLG Director of Research and Education) The current style of legal pedagogy was introduced in 1870 when Harvard Law School Dean Christopher Colombus Langdell initiated the use of the casebook method and the Socratic method, practices which were eventually institutionalized in American legal education, along with the use of the curve model of grading. Unlike many other higher education programs, the teaching and grading practices of law school are often deliberately confusing and intimidating. While the actual material is not always difficult to understand, the methods by which professors present information and assign grades produces anxiety and stress among students, as shown in the section on the psychological effects of law school. Furthermore, the teaching methods, grading system, and curriculum of legal education have evolved to promote and reinforce the desires of the elite, or what Nikki Demetria Thanos calls “the pedagogy of the oppressor.”1 In this section, we discuss the most common attributes of American legal pedagogy—the Socratic method, the casebook method, and the grading system—and offer suggestions for reforms in legal education that are more conducive to critical thinking, skills developments, and accurate assessment of student progress and understanding of material. The next section takes on the issue of curriculum, with suggestions for incorporating the insights of critical legal studies into law school programs. Legal Pedagogy American law school classes are generally structured to rely on a combination of the Socratic method—the form of teaching based on asking and answering questions—and the casebook method—reading illustrative examples of judicial principles. -

Legal Education and the Public Interest, 1948

JOURNAL OF LEGAL EDUCATION Volume I Winfer, 1948, Number 2 LEGAL EDUCATION AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST, 1948 RALPH F. FuCHas * t requires no demonstration to show that lawyers are prominent among those who today are grappling with national and international problems of unprecedented gravity. Obviously; too, this situation will continue indefinitely in business and public affairs. A major concern of law schools must be the adequacy of the equipment of their. future graduates for participation in such matters; and this concern arises with added urgency at a'time when opportunity exists for readjustments in legal education as the post-war plateau is reached, provided anoth&r war can be avoided. It may be worth while, therefore, to attempt a brief appraisal of the present state of legal education and to suggest two developments in university training for law which, although close- ly related to numerous previous proposals, assume their particullar char- acter because of the world's current state. At present the outstanding facts about American legal education are the unprecedented number of students enrolled and the continued reli- .ance of schools upon curricula which have the appearance of being large- ly the same as two decades ago. The appearance of the curricula is, to be sure, to some extent deceptive; for within the courses that still bear the same names or still cover essentially the same ground under other names, new "coursebooks" and changed attitudes and methods on the part of instructors have come to prevail. Essentially, however, the summary supplied by the 1947 Curriculum Committee of the Associa- tion of American Law Schools is correct. -

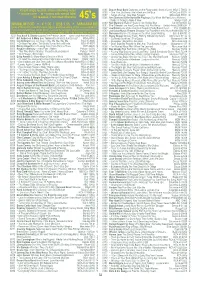

Minimum Bod = 6 1.00 / Us$ 1.15 = Minimum

45 rpm single records, unless otherwise noted 6085 Desert Rose Band Darkness on the Playground | Story of Love MCA-C 79052 N 6086 ~ One That Got Away | He’s Back and I’m Blue MCA-Curb 53274 N * = picture cover · pr = promo with special label 6087 ~ Ashes of Love | One Step Forward MCA-Curb 53531 N US releases, if not noted otherwise 45's 6088 Ann Diamond & the Nashville Playboys You Make Me Feel Like a Woman | I Think I’m Going to Make It Now Marilyn 7063 N 6089* Neil Diamond Walk on Water | High Rolling Man Uni 6073045\D Zg MINIMUM BOD = € 1.00 / US$ 1.15 = MINIMUM BID 6090 The Dillards Love Has Gone Away | Hot Rod Banjo United Artists 35660\UK Z Some of these 45’s come from radio stations and have writing and/or stickers on labels. 6091* Joe Dolan Love of the Common People | Pretty Brown Eyes Pye 11088\D Zg If you do not want those, let me know! - Een aantal van deze singles komt van radio sta- 6092* Joe Dolce Music Theatre Shaddap You Face|Ain’t in No HurryAriola102947\D Zz tions, waar men op labels schreef en/of stickers plakte. Wilt u die niet, laat het me weten! 6093 Donovan Atlantis | To Susan on the West Coast Waiting Epic 5-9967\D G 6233 Roy Acuff & Charlie Louvin The Precious Jewel (gold vinyl) Hal Kat 63058 Z 6094 Rusty Draper Mystery Train | Shifting Whispering Sands Monument 944 pr N 6001 Bill Anderson & Mary Lou Turner Way Ahead | Just Enough MCA 40852 Z 6095 ~ California Sunshine | The Gypsy Monument 1044 N 6002 Liz Anderson Cry, Cry Again | Me, Me, Me, Me, Me RCA 47-9586 Z 6096 ~ Puppeteer | My Baby’s Not Here Monument -

[I`I1 I Radio Knows Destiny's Name

JANUARY 7, 2000 ISSUE 2286 THE MOST TRUSTED NAME IN RADIO -MUSIC TOP 40 Backstreet's Back... In a Big Way RHYTHM [i`i1 I Radio Knows Destiny's Name HOT AIC Sugar Ray Falls Up ALTERNATIVE Chili's Otherside is Hot COUNTRY Faith Greets Y2K at #1 URBAN Jay -Z Does it Again } NEWS Arbitron Delays Fall Book Release AMFM, CNET In Radio Venture Universal Wins 1999 Sales Battle Home of the / Seminar in Radio G2K in SF0-Feb. 16-20, 2000 From the Publishers of Music Week, MBI and fono A Miller Freeman Publication www.jessicaandrews.corrm www.dreamworksrecords.zom 0 1999 DREAMWORKS RECORDS NASI -VILLE www.americanradiohistory.com "how do you like me 00 Racing into the New M Ilennium www.tobykeith.com © 1999 mWorks Records Nashville www.dreamworksrecords.co www.americanradiohistory.com Sweethearts Don't Run "You cant be Hollywood's sweetheart if you're running from the cops." - JENNIFER LOPEZ COMMENTING TO NEWSWEEK, FOLLOWING A SKIRMISH AT A NEW YORK NIGHTCLUB IN WHICH BOYFRIEND SEAN "PUFFY" COMBS IS ACCUSED OF SHOOTING THREE PEOPLE. I'm Not the NRA I do nt x own a gun. I do not carry a gun. The charges and allegations against me are 100 percent false...I had nothing to do with the shooting in the nightclub." - Comm, Arbitron Delays AN I ER HIS ARREST AND SUBSEQUENT LAWSUIT FILED BY JULIUS JONES, ONE OF THE PEOPLE WHO WAS SHOT. Fall Book Release Merit Scout "Frivolous and without merit." - COMBS' ATTORNEY, "The good news is that our sys- development of a new diary pro- HARVEY SLOVIS, COMMENTING ON THE LAWSUIT. -

Beachersep02.Pdf

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 37, Number 34 Thursday, September 2, 2021 THE Page 2 September 2, 2021 THE 911 Franklin Street • Michigan City, IN 46360 219/879-0088 Beacher Company Directory e-mail: News/Articles - [email protected] Don and Tom Montgomery Owners email: Classifieds - [email protected] Andrew Tallackson Editor http://www.thebeacher.com/ Drew White Print Salesman PRINTE ITH Published and Printed by Janet Baines Inside Sales/Customer Service T Randy Kayser Pressman T A S A THE BEACHER BUSINESS PRINTERS Dora Kayser Bindery Jacquie Quinlan, Jessica Gonda Production Delivered weekly, free of charge to Birch Tree Farms, Duneland Beach, Grand Beach, Hidden Shores, Long Beach, Michiana Shores, Michiana MI and Shoreland Hills. The Beacher is John Baines, Karen Gehr, Tom Montgomery Delivery also delivered to public places in Michigan City, New Buffalo, LaPorte and Sheridan Beach. AAnn IIdyllicdyllic LLifeife by Connie Kuzydym Micky Gallas is photographed by The Beacher’s Bob Wellinski along the Lake Michigan shoreline. Editor’s note — This is the next in an ongoing se- ries amid this year’s Long Beach centennial anni- versary highlighting history, individuals and orga- nizations in the community. hen Long Beach was fi rst established 100 years ago, it was a resort community draw- Wing predominantly from Chicago. Eventu- ally, the area near Lake Michigan began resonating with those who wanted to raise their children near the sand and water. As the years passed, there were generations of families sprinkled throughout the beach area. One such family is the O’Haras.