A New-Old Notion of Cult

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piercing the Religious Veil of the So-Called Cults

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 7 Issue 3 Article 6 4-15-1980 Piercing the Religious Veil of the So-Called Cults Joey Peter Moore Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Joey Peter Moore Piercing the Religious Veil of the So-Called Cults , 7 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 3 (1980) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol7/iss3/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Piercing the Religious Veil of the So-Called Cults Since the horror of Jonestown, religious cults have been a frequent sub- ject of somewhat speculative debate. Federal and state governments, and private groups alike have undertaken exhaustive studies of these "cults" in order to monitor and sometimes regulate their activities, and to publicize their often questionable tenets and practices. The author offers a compre- hensive overview of these studies, concentrating on such areas as recruit- ment, indoctrination, deprogramming, fund raising, and tax exemption and evasion. Additionally, the author summarizes related news events and profiles to illustrate these observations,and to provide the stimulusfor further thought and analysis as to the impact these occurrences may have on the future of religion and religiousfreedom. I. INTRODUCTION An analysis of public opinion would likely reveal that the exist- ence of religious cults' is a relatively new phenomenon, but his- torians, social scientists and students of religion alike are quick to point out that such groups, though cyclical in nature, have simi- 2 larly prospered and have encountered adversity for centuries. -

Paul Morantz (Page 13) Abank in the Village Last Year, Has We Launched a Major and Aggres- Fire Scares Within a Week of Each Plead Guilty to Four Bank Robberies

Palisadian-Post Serving the Community Since 1928 24 Pages Thursday, March 15, 2018 ◆ Pacific Palisades, California $1.50 Let’s Play Ball! Amazon Books Heading to Palisades Village By SARAH SHMERLING is an area “that we know is full of leased, with Amazon Books the Managing Editor readers.” 18th confirmed tenant. Palisadians have not turned At the three Amazon stores he next chapter of Caruso’s the pages at a local store since Vil- currently in California titles are laid Palisades Village has been lage Books closed its doors in June with covers rather than spines out. Twritten: Amazon has signed up to 2011, despite a fierce fight by -lo At the flagship store in Seattle, create a “bricks and mortar” store cals, including Tom Hanks, to save which stocks 6,000 books initially when the project opens on Sept. 22. it. chosen through its “social cata- “We created Amazon Books to Other retailers at the loging” website Goodreads, there be a place where customers discov- 125,000-square-foot complex will has been a list of recommended er books and devices they’ll love,” include SunLife Organics, Vintage volumes by Amazon founder Jeff Cameron Janes, vice president of Grocers and Cinépolis’ Bay The- Bezos. Amazon Books, told the Los Ange- atre. It includes his wife MacKenzie les Times. Caruso reported that 80 percent Tuttle Bezos’ Hollywood thriller He also noted that the Palisades of the 40-plus spaces have been “Traps.” Big, Worried Crowd for Safety Town Hall Councilmember Mike Bonin takes on questions. Rich Schmitt/Staff Photographer By CHRISTIAN MONTERROSA cars was a relief, as the impending Pali High, ensured parents that Reporter threat by the California regulators the school is increasing security to eliminate local beach’s mid- measures as the consideration of a oncerned for safety, privacy night-to-5 a.m. -

Story Ideas for Journalists Connections, Events, and Advocacy

Story Ideas for Journalists [email protected] | DeadInsaneOrInJail.com • Children’s rights / human rights • Institutionalized persuasion (coercion) • Social isolation during adolescence • Milieu control (brainwashing) • Decisions for institutional placement • Making art from trauma • Healthy attachment and trauma bonding • Art as the antidote to abuse Connections, Events, and Advocacy Groups: Virginia Festival of the Book MARCH 2018, CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA • Dead, Insane, or in Jail: Overwritten is featured on the panel discussion, “Seeking Wellness: We Are Not Alone,” about memoir and understanding. International Cultic Studies Association JULY 2016, DALLAS, TX • After attending the ICSA conference in Stockholm in 2015, Zack was invited to present the following year in Dallas, with his session, “The Lack of Research in Adolescent Group Settings: Psychological Pressures as Part of the Milieu in Controlling Institutions and Systems - Making Art out of the Inexpressible.” While there, at a Phoenix Project session on the role of the arts in resistance and recovery, Zack read from Book One and made the case that art is the antidote to authoritarianism. (icsahome.com) Virginia Festival of the Book MARCH 2016, CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA • Book One in the series, Dead, Insane, or in Jail: A CEDU Memoir, was selected for the 2016 Virginia Festival of the Book, and was featured in the local paper. To a packed house, Zack engaged in a public discussion with other experts about consent and coercion in mental health treatment policy. (VaBook.org) Daedalus Books Debut Event NOVEMBER 2015, CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA • Iconic used-bookseller Deadalus Books introduced Dead, Insane, or in Jail: A CEDU Memoir to local friends, fans, and supporters in Zack’s inaugural book event. -

GATES V. DEUKMEJIAN 23 Vs

J.S. v. Cal. • ••< H • V H H W • • • I PC-CA-013-006 1 McCUTCHEN, DOYLE, BROWN & ENERSEN WARREN E. GEORGE (State Bar # 053588) 2 Three Embarcadero Center San Francisco, CA 94111 3 Telephone: (415) 393-2000 4 PRISON LAW OFFICE ROSEN & PHILLIPS DONALD SPECTER (# 083925) SANFORD JAY ROSEN (# 062566) 5 MILLARD MURPHY (# 124451) PAUL A. Di DONATO (# 124962) Freedom Mall, Main Street 155 Montgomery Street 6 San Quentin, CA 94964 8th Floor Telephone: (415) 457-9144 San Francisco, CA 94104 7 Telephone: (415) 433-6830 BROBECK, PHLEGER & HARRISON 8 MICHAEL W. BIEN (# 096891) ACLU FOUNDATION OF NORTHERN Spear Street Tower CALIFORNIA, INC. 9 One Market Plaza MATTHEW A. COLES (# 076090) San Francisco, CA 94105 1663 Mission Street 10 Telephone: (415) 442-0900 San Francisco, CA 94103 Telephone: (415) 621-2493 11 Attorney for Plaintiffs 12 13 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 14 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 15 16 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. CIV S-89-1233 EJG-JFM 17 Plaintiffs, 18 vs. STATE OF CALIFORNIA, et al., 19 Defendants. 20 21 JAY LEE GATES, et al., No. CIV S-87-1636 LKK-JFM 22 Plaintiffs, COMPLAINT IN INTERVENTION OF PLAINTIFFS IN GATES V. DEUKMEJIAN 23 vs. 24 GEORGE DEUKMEJIAN, et al., 25 Defendants. 26 455\2\complnt9.o20 - 1 - COMPLAINT IN INTERVENTION OF PLAINTIFFS 1 2 FIRST CAUSE OF ACTION 3 I. NATURE OF ACTION 4 l. Plaintiffs, prisoners incarcerated at the California 5 Medica Facility ("CMF") and at the Northern Reception Center 6 ("NRC"), bring this action to remedy the legally deficient medical 7 care and psychiatric care that are presently being provided at CMF 8 and NRC. -

B. Taxation of Revoked Tax-Exempt Organizations

B. TAXATION OF REVOKED TAX-EXEMPT ORGANIZATIONS: THE SYNANON CASE 1. Background When attorney Paul Morantz discovered the hard way that a four-foot rattlesnake was residing in his mailbox one day in October 1978, he had more pressing concerns than to wonder about the possible income tax implications of the event. Although he immediately might have suspected that his representation of two former Synanon members in a lawsuit against the Synanon Church, then recognized as an IRC 501(c)(3) organization, could have inspired retribution by the organization, he doubtless would not have foreseen, or at that moment much cared about, the subsequent administrative actions that resulted in the revocation of Synanon's exempt status, Synanon's legal attempts to regain that status, and its persistence throughout the entire period, both before and after revocation, in holding itself out to contributors as a charitable organization. The rattlesnake incident was far from the only questionable activity of the Synanon Church, but it was certainly the one that most captured the attention of the police, the press, and the IRS. As detailed in Synanon Church v. U.S., 579 F.Supp. 967 (D.C., D.C., 1984), in a 1977 speech called "New Religious Posture", Charles Dederich, Synanon's founder, had warned "Don't mess with us. You can get killed dead. Physically dead." Groups were organized to carry on a "Holy War" against Synanon's enemies, and Synanon had been tied to a number of beatings and acts of physical violence. During the summer preceding the incident, while Synanon officials were in Italy, phone calls were made to the United States in an attempt to arrange Mr. -

The Technicolor World of Paul Morantz

Palisadian-Post Thursday, March 15, 2018 Page 13 Morantz after the reptile attack Photo courtesy of Paul Morantz Photos by Rich Schmitt/ Staf Photographer The Technicolor World of Paul Morantz By MARIE TABELA Forty years later, sitting in his shad- Special to the Palisadian-Post owy living room, Morantz does not like to dwell on his long recovery. But he still n display in a home tucked away in feels it was a worthwhile victory over one ORustic Canyon is an unusual wall of many such groups who believed they decoration: a nearly fve-foot-long replica were waging a holy war. of a rattlesnake that was once deployed Surrounded by mementos of an ex- as a murder weapon. It was handmade by traordinary life, walls covered with one of the members of the very cult who Disney flm cells and Golden Age Hol- concocted the plan. lywood beauties, as well as an amazing The real thing nearly killed its host, array of tributes to his personal hero Davy civil rights attorney Paul Morantz. Crockett, Morantz spoke in hushed tones And today, sadly, that injury may be about evil men. catching up with him, proving to be a A West Los Angeles native, he served mortal wound. in the U.S. Army as a reservist in 1963. All along Morantz knew that, as a He attended USC where he became ferce critic of the more dangerous cults sports editor for the school newspaper that followed the Age of Aquarius, he had The Daily Trojan and earned his law de- made enemies. -

John Gottuso Sentencing

John Gottuso Sentencing http://www.paulmorantz.com/cult/john-gottuso-sentencing/ ( index.php ) Paul Morantz ( http://www.paulmorantz.com ) paulmorantz.com Home ( http://www.paulmorantz.com ) Jan & Dean ( http://www.paulmorantz.com/jan-dean/ ) The Cult Expert ( http://www.paulmorantz.com/the-cult-expert/ ) Book– Escape: My Life Long War Against Cults ( http://www.paulmorantz.com/book-escape-my-life-long-war-against-cults/ ) Stories ( http://www.paulmorantz.com/stories/ ) Synanon ( http://www.paulmorantz.com/the_synanon_story/ ) USC Sports ( http://www.paulmorantz.com/usc-sports/ ) Friends ( http://www.paulmorantz.com/friends/ ) Contact ( http://www.paulmorantz.com/contact/ ) Posts ( http://dev.sloshanty.com/projects/PaulMorantz/?feed=rss2 ) Comments ( http://dev.sloshanty.com/projects/PaulMorantz/?feed=comments-rss2 ) John Gottuso Sentencing Meta Log in ( http://www.paulmorantz.com By the time the Pasadena City Attorney Office filed on John Gottuso most of his alleged abuse of students /wp-login.php ) statue of limitations had lapsed. One case proceeded. The victim was not my client but she allowed me to Entries RSS speak for her that day. My speech was nothing more than asking his past victims to stand up in court. “Will (http://www.paulmorantz.com/feed/ ) the victims of the 60’s please stand,” I said. “Now those of the 70’s…..The Eighties please…now the 90’s…” Comments RSS (http://www.paulmorantz.com I explained to the court I wanted Gottuso to know the court now knew what he was and that if there were /comments/feed/ ) victims in the next century Gottuso would know the court would put him behind bars for as long as possible. -

Louis Jolyon West Papers LSC.0590

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c84j0hcd No online items Finding Aid for the Louis Jolyon West Papers LSC.0590 Finding aid prepared by Jolene Beiser, 2009. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2019 August 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Louis Jolyon LSC.0590 1 West Papers LSC.0590 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Louis Jolyon West papers Creator: West, Louis Jolyon Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0590 Physical Description: 106 Linear Feet(265 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1890-1998 Date (bulk): 1948-1998 Abstract: Louis Jolyon (Jolly) West, M.D. (1924-1999) was a well-known Los Angles psychiatrist who served as the chair of UCLA's Department of Psychiatry and as director of the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute from 1969 to 1989. He was an expert on cults, coercive persuasion ("brainwashing"), alcoholism, drug abuse, violence, and terrorism. The collection contains Dr. West's research materials, lecture and presentation materials, personal and professional correspondence, and documents related to his professional associations and academic positions. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Conditions Governing on Access Open for reserach with the following exceptions: Boxes 250-265 are not available due to HIPAA restrictions. Please contact Special Collections reference ([email protected]) for more information. -

Supervisors Kill Proposed Noise Ordinance for S.B

N Supervisors Kill Proposed Noise Ordinance for S.B. By GINA DUNCAN the proposal, Fletcher changed his cerns of the no voters was the cost The Santa Bárbara County mind today by saying that he felt of enforcing the program; John Board of Supervisors voted 3-2 an ordinance was needed, but he Stall, assistant to Wallace, against a proposed noise control wasn’t sure he was willing to pay estimates this cost to be ap ordinance yesterday. The or as much as it cost for that or proximately $40,000 a year. dinance, if adopted, would have dinance. He was also concerned “ Mr. Wallace feels that the required that noise be kept down to about adding “ another layer of existing disturbing of the-peace 45 decibels after 10 p.m. government” after Proposition 13. law is adequate,” Stall said later. This ordinance itself was The County Administrative However, according to Dale prompted by a state mandate Officer indicated that enforcement Clark, a member of the Citizens which required counties to include costs could not presently be Noise Abatement Committee, the sound controls in their county justified. law presently prohibits only loud master plan. It seems one of the main con (Please turn to pg.8, col.2) “ The ordinance would be very hard to enforce,” said Bill Wallace, 3rd District Supervisor. Student Enrollment “ Especially in Isla Vista where housing is situated so close together.” O ff for Fall Quarter He said that the ordinance was By MICHELLE TOGUT impractical for LV. because of Enrollment at UCSB for the fall quarter is only 27 students short of stereo volume, parties and normal projected enrollment figures. -

8 9 Former FBI Chief Robert Mueller to Probe Russia-Trump Links

www.theindianpanorama.com VOL 5 ISSUE 20 ● DALLAS ● MAY 19 - MAY 25, 2017 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 ● PRICE 40 CENTS Why the Special Counsel may be The Threat from Deepika Padukone Good News for Republicans and Problematic dons an easy breezy 8 Bad News for Trump 9 Organizations and Cults 12 silk dress in Cannes International Court of Justice, The Hague stays Former FBI chief Robert Mueller to Jadhav execution probe Russia-Trump links Diplomatic victory for India as ICJ asks defiant Pakistan to implement ruling Trump decries special counsel's appointment as 'single greatest witch-hunt' in US history WASHINGTON (TIP) ormer FBI director Robert Mueller has been appointed as Fspecial counsel to investigate alleged Russian interference in the 2016 US election and possible collusion between President Donald Trump's campaign and Moscow. The decision by deputy attorney general Rod Rosenstein to appoint Mueller, 72, as special counsel came on Wednesday, May 17, following a week of Presiding judge Ronny Abraham of France reads the World Court's verdict in The Hague, Netherlands. turmoil for the White House after Trump fired FBI Director James NEW DELHI (TIP): The Comey, who had been leading a federal International Court of Justice probe into the matter. (ICJ), on May 18, stayed the Rosenstein said he had taken the execution of Kulbhushan decision "to ensure a full and thorough Jadhav until it rules on the investigation of the Russian merits of the case. government's efforts to interfere in the The stay passed 2016 presidential election," including -

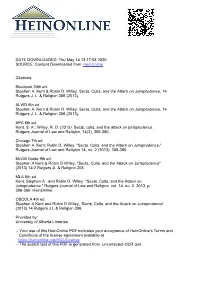

Sects, Cults, and the Attack on Jurisprudence. Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion, 14(2), 306-360

DATE DOWNLOADED: Thu May 14 13:17:08 2020 SOURCE: Content Downloaded from HeinOnline Citations: Bluebook 20th ed. Stephen A. Kent & Robin D. Willey, Sects, Cults, and the Attack on Jurisprudence, 14 Rutgers J. L. & Religion 306 (2013). ALWD 6th ed. Stephen A. Kent & Robin D. Willey, Sects, Cults, and the Attack on Jurisprudence, 14 Rutgers J. L. & Religion 306 (2013). APA 6th ed. Kent, S. A.; Willey, R. D. (2013). Sects, cults, and the attack on jurisprudence. Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion, 14(2), 306-360. Chicago 7th ed. Stephen A. Kent; Robin D. Willey, "Sects, Cults, and the Attack on Jurisprudence," Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion 14, no. 2 (2013): 306-360 McGill Guide 9th ed. Stephen A Kent & Robin D Willey, "Sects, Cults, and the Attack on Jurisprudence" (2013) 14:2 Rutgers JL & Religion 306. MLA 8th ed. Kent, Stephen A., and Robin D. Willey. "Sects, Cults, and the Attack on Jurisprudence." Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion, vol. 14, no. 2, 2013, p. 306-360. HeinOnline. OSCOLA 4th ed. Stephen A Kent and Robin D Willey, 'Sects, Cults, and the Attack on Jurisprudence' (2013) 14 Rutgers J L & Religion 306 Provided by: University of Alberta Libraries -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. SECTS, CULTS, AND THE ATTACK ON JURISPRUDENCE1 Stephen A. Kent* and Robin D. Willey** ABSTRACT This article examines the anti-juridical doctrines and actions of various religious and religiously-related sects and cults in the United States and Canada. -

CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY Paul Morantz a Basis for The

CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY Paul Morantz A basis for the representation, manufacturing tool path generation and scanning measurement of smooth freeform surfaces School of Aerospace, Transport and Manufacturing PhD Thesis Academic Year: 2016 - 2017 CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY School of Aerospace, Transport and Manufacturing PhD Academic Year 2016 - 2017 Paul Morantz A basis for the representation, manufacturing tool path generation and scanning measurement of smooth freeform surfaces Supervisor: Paul Shore February 2017 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Cranfield University 2017. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright owner. ABSTRACT Freeform surfaces find wide application, particularly in optics, from unique single- surface science programmes to mobile phone lenses manufactured in billions. This thesis presents research into the mathematical and algorithmic basis for the generation and measurement of smooth freeform surfaces. Two globally significant cases are reported: 1) research in this thesis created prototype segments for the world’s largest telescope; 2) research in this thesis made surfaces underpinning the redefinition of one of the seven SI base units – the kelvin - and also what will be the newly (and permanently) defined value for the Boltzmann constant. The research demonstrates two underlying philosophies of precision engineering, the critical roles of determinism and of precision measurement in precise manufacturing. The thesis presents methods, and reports their implementation, for the manufacture of freeform surfaces through a comprehensive strategy for tool path generation using minimum axis-count ultra-precision machine tools. In the context of freeform surface machining, the advantages of deterministic motion performance of three-axis machines are brought to bear through a novel treatment of the mathematics of variable contact point geometry.