Abortion, Population Control and Transnational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personhood Seeking New Life with Republican Control Jonathan Will Mississippi College School of Law, [email protected]

Mississippi College School of Law MC Law Digital Commons Journal Articles Faculty Publications 2018 Personhood Seeking New Life with Republican Control Jonathan Will Mississippi College School of Law, [email protected] I. Glenn Cohen Harvard Law School, [email protected] Eli Y. Adashi Brown University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.mc.edu/faculty-journals Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons Recommended Citation 93 Ind. L. J. 499 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at MC Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of MC Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Personhood Seeking New Life with Republican Control* JONATHAN F. WILL, JD, MA, 1. GLENN COHEN, JD & ELI Y. ADASHI, MD, MSt Just three days prior to the inaugurationof DonaldJ. Trump as President of the United States, Representative Jody B. Hice (R-GA) introducedthe Sanctity of Human Life Act (H R. 586), which, if enacted, would provide that the rights associatedwith legal personhood begin at fertilization. Then, in October 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services releasedits draft strategicplan, which identifies a core policy of protectingAmericans at every stage of life, beginning at conception. While often touted as a means to outlaw abortion, protecting the "lives" of single-celled zygotes may also have implicationsfor the practice of reproductive medicine and research Indeedt such personhoodefforts stand apart anddistinct from more incre- mental attempts to restrictabortion that target the abortionprocedure and those who would perform it. -

Involuntary Sterilization in the United States: a Surgical Solution

VOLUME 62, No.2 THE QUARTERLY REVIEW OF BIOLOGY JUNE 1987 INVOLUNTARY STERILIZATION IN THE UNITED STATES: A SURGICAL SOLUTION PHILIP R. REILLY Eunice Kennedy Shriver Center, Waltham) Massachusetts 02254 USA ABSTRACT Although the eugenics movement in the United Statesflourished during the first quarter ofthe 20th Century, its roots lie in concerns over the cost ofcaring for ((defective" persons, concerns that first became manifest in the 19th Century. The history ofstate-supported programs ofinvoluntary sterili zation indicates that this ((surgical solution" persisted until the 1950s. A review of the archives ofprominent eugenicists, the records ofeugenic organizations, important legal cases, and state reports indicates that public support for the involuntary sterilization ofinsane and retarded persons was broad and sustained. During the early 1930s there was a dramatic increase in the number ofsterilizations performed upon mildly retardedyoung women. This change in policy was aproduct ofthe Depression. Institu tional officials were concerned that such women might bear children for whom they could not provide adequate parental care, and thus would put more demands on strained sodal services. There is little evidence to suggest that the excesses of the J.Vazi sterilization program (initiated in 1934) altered American programs. Data are presented here to show that a number ofstate-supported eu genic sterilization programs were quite active long after scientists had refuted the eugenic thesis. BACKGROUND lums there was growing despair as the mid century thesis (Sequin, 1846) that the retarded T THE CLOSE of the 19th Century in and insane were educable faded. About 1880, Athe United States several distinct develop physicians who were doing research into the ments coalesced to create a climate favorable causes ofidiocy and insanity developed the no to the rise of sterilization programs aimed at tion ofa "neuropathic diathesis" (Kerlin, 1881) criminals, the insane, and feebleminded per that relied on hereditary factors to explain sons. -

From Far More Different Angles: Institutions for the Mentally Retarded in the South, 1900-1940

"FROM FAR MORE DIFFERENT ANGLES": INSTITUTIONS FOR THE MENTALLY RETARDED IN THE SOUTH, 1900-1940 By STEVEN NOLL A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1991 To Dorothy and Fred Noll, and Tillie Braun. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the five years this work has consumed my life, I have accumulated more debts than I care to imagine- I can never repay them; all I can do is acknowledge them with heartfelt thanks and hope I haven't left anyone out. The financial help provided by the University of Florida Department of History was essential, for without it, this project could not have even been started, much less completed. I would also like to thank the Rockefeller Archive Center, Pocantico Hills, New York and the North Caroliniana Society of Chapel Hill, North Carolina for their travel to collection grants which enabled me to conduct much of my research. My supervising committee has provided me with guidance, support, and help at every step of the process. Special thanks to Kermit Hall, my chairman, for his faith in my abilities and his knack for discovering the truly meaningful in my work. He always found time for my harried questions, even in the middle of an incredibly busy schedule. The other committee members, Robert Hatch, Michael Radelet, Bertram Wyatt-Brown, and Robert Zieger, all provided valuable intellectual advice and guidance. Michael Radelet also proved that good teaching, good research, and social 111 activism are not mutually exclusive variables. -

With Special Thanks to Siemens for Sponsoring the Research and Interviews Required to Present This Innovation Special Section

With special thanks to Siemens for sponsoring the research and interviews required to present this innovation special section. GMA CENTENNI A L SPE C I A L Iss UE 2008 FORUM 111 A Survey of Astonishing Accomplishment To some naysayers today, “CPG What do you see? innovation” is an oxymoron, but in fact Everywhere you look, you –– we –– see CPG products that nothing could be further from the truth. make our lives easier, cleaner, lighter, brighter, safer, better nourished, more satisfying and, in so many ways, sweeter. The breadth, depth and variety of innovation in product, formulation, packaging, manufacturing, marketing, distribution, What did our grandparents see? Well? business process, collaboration and co-invention that has characterized CPG for more than a century –– and that is What is the difference? occurring inside hundreds of companies as you’re reading this –– is nothing short of mind-boggling. The difference is a century of explosively creative response to consumer needs. In a word, innovation. Why is it that this remarkable record –– this staggering difference between our choices and those available to our So, this year, 2008, the 100th Anniversary of the Grocery grandparents or great-grandparents when they were our age Manufacturers Association, we celebrate this astonishing –– doesn’t take our breath away? CPG century with a decade-by-decade overview of a barely representative few of the thousands upon thousands of remarkable THE CPG CENTURY Only, perhaps, because we are, as psychologists might say, CPG accomplishments over the past 100 years –– innovations that “habituated” –– we have lost our sense of wonder because we cover the CPG spectrum from products and advertising we recall Years of live with all these options every day. -

S.C. Education Department Is 'Very Concerned' About Mayewood

LOCAL: Best Of contest expands to Clarendon for 1st year A8 CLARENDON SUN Firefighters awarded at annual banquet A7 SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2019 75 CENTS S.C. education Punching up the confidence meter department is ‘very concerned’ about Mayewood Official letter sent to district, board chairman after reopening decision BY BRUCE MILLS [email protected] ESTIMATED COSTS TO REOPEN MAYEWOOD The state education depart- First-year costs in 2019-20: ment’s leader wrote a letter to $1 million to $1.2 million Sumter School District’s leaders Reoccurring annual costs: $360,000 expressing concerns about the to $471,000 school board’s vote Monday night to re- Source: Sumter School District administration open Mayewood Mid- dle School given the district’s recent fi- education department, told The nancial and other Sumter Item on Thursday. difficulties. After the official fiscal 2016 SPEARMAN South Carolina Su- audit report revealed the district perintendent of Edu- overspent its budget by $6.2 mil- cation Molly Spearman brought lion that year, draining its gener- up a handful of topics that are ei- al fund balance to $106,449, the ther ongoing or in the recovery state department put the district process, mainly regarding costs on a “fiscal watch” in 2017. associated with reopening and That same year, the state Legis- maintaining Mayewood and pos- lature passed a law requiring all sibly F.J DeLaine Elementary school districts to have at least School next school year. one month’s operating expendi- KAYLA ROBINS / THE SUMTER ITEM “We’re very much aware of the tures in their fund balance — Jerome Robinson owns Team Robinson MMA in Sumter, which moved into the former Jack’s issues going on in Sumter, and roughly $12 million for Sumter’s Shoes downtown in 2018. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS April 13, 1989 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS Yielding to Extraordinary Economic Pres Angola

6628 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS April 13, 1989 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS Yielding to extraordinary economic pres Angola. Already cut off from South African TESTIMONY OF HOWARD sures from the U.S. government, South aid, which had helped stave off well funded PHILLIPS Africa agreed to a formula wherein the anti invasion-scale Soviet-led assaults during communist black majority Transitional 1986 and 1987, UNITA has been deprived by HON. DAN BURTON Government of National Unity, which had the Crocker accords of important logistical been administering Namibia since 1985, supply routes through Namibia, which ad OF INDIANA would give way to a process by which a new joins liberated southeastern Angola. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES government would be installed under United If, in addition, a SWAPO regime were to Thursday, April 13, 1989 Nations auspices. use Namibia's Caprivi Strip as a base for South Africa also agreed to withdraw its anti-UNITA Communist forces, UNITA's Mr. BURTON of Indiana. Mr. Speaker, I estimated 40,000 military personnel from ability to safeguard those now resident in would like to enter a statement by Mr. Howard Namibia, with all but 1,500 gone by June 24, the liberated areas would be in grave ques Phillips of the Conservative Caucus into the to dismantle the 35,000-member, predomi tion. RECORD. In view of recent events in Namibia, nantly black, South West African Territori America has strategic interests in south al Force, and to permit the introduction of ern Africa. The mineral resources concen I think it is very important for all of us who are 6,150 U.N. -

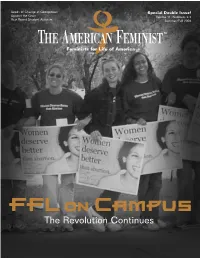

Summer-Fall 2004: FFL on Campus – the Revolution Continues

Seeds of Change at Georgetown Special Double Issue! Against the Grain Volume 11, Numbers 2-3 Year-Round Student Activism Summer/Fall 2004 Feminists for Life of America FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues ® “When a man steals to satisfy hunger, we may safely conclude that there is something wrong in society so when a woman destroys the life of her unborn child, it is an evidence that either by education or circumstances she has been greatly wronged.” Mattie Brinkerhoff, The Revolution, September 2, 1869 SUMMER - FALL 2004 CONTENTS ....... FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues 3 Revolution on Campus 28 The Feminist Case Against Abortion 2004 The history of FFL’s College Outreach Program Serrin Foster’s landmark speech updated 12 Seeds of Change at Georgetown 35 The Other Side How a fresh approach became an annual campus- Abortion advocates struggle to regain lost ground changing event 16 Year-Round Student Activism In Every Issue: A simple plan to transform your campus 38 Herstory 27 Voices of Women Who Mourn 20 Against the Grain 39 We Remember A day in the life of Serrin Foster The quarterly magazine of Feminists for Life of America Editor Cat Clark Editorial Board Nicole Callahan, Laura Ciampa, Elise Ehrhard, Valerie Meehan Schmalz, Maureen O’Connor, Molly Pannell Copy Editors Donna R. Foster, Linda Frommer, Melissa Hunter-Kilmer, Coleen MacKay Production Coordinator Cat Clark Creative Director Lisa Toscani Design/Layout Sally A. Winn Feminists for Life of America, 733 15th Street, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20005; 202-737-3352; www.feministsforlife.org. President Serrin M. -

The Inventory of the Faith R. Whittlesey Collection #1173

The Inventory of the Faith R. Whittlesey Collection #1173 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Whittlesey, Faith #1173 4/3/1989 Preliminary Listing I. Subject Files. Box 1 A. “Before You Leave.” [F. 1] B. “China Trip.” [F. 2-3] II. Financial Materials. A. General; includes checks and bank statements . [F. 4] III. Correspondence. A. General,1984-1985; notables include: [F. 5] 1. Reagan, Ronald. TLS, 10/18/83. IV. Printed Materials. A. General; includes magazines, newspaper clippings. [F. 6-7] V. Notebooks. A. 2 items, n.d. [F. 8] VI. Photographs. A. 181 color, 48 black and white prints. [F. 9, E. 1-3] VII. Personal Memorabilia. A. General; includes hats; hot pads; driver’s license; plate decoration. [F. 10] VIII. Audio Materials. A. 2 cassettes tapes. [F. 11] Whittlesey, Faith #1173 4/3/89- 5/21/03 Preliminary Listing I. Manuscripts. Box 2 A. General re: speeches,1985. [F. 1-4] II. Correspondence. A. General, ALS, TLS, TL, ANS, telegrams, greeting cards, 1984-1986; notables include: 1. Reagan, Ronald. Carbon copy to Jon Waldarf, 11/5/86. [F. 5] 2. Murdoch, Rupert. TLS to FW, 12/24/85. 3. O’Conner, Sandra Day. TLS to FW, 6/4/85. B. “Swiss,” file. C. General, 1984-1987. [F. 6-8] III. Professional Materials. A. Files 1. “Information.” [F. 9] 2. “Ambassador Whittlesey 1602.” [F. 10] 3. “Thursday, Dec. 12.” 4. “The Ambassador’s Schedule.” 5. “Pres. Visit Nov. 1985 Take to Geneva.” 6. “Untitled re: Brefig Book.” 7. “1984-1986.” [F. 11-14] IV. Printed Materials. A. General, 1985-1986. -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

Does the Fourteenth Amendment Prohibit Abortion?

PROTECTING PRENATAL PERSONS: DOES THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT PROHIBIT ABORTION? What should the legal status of human beings in utero be under an originalist interpretation of the Constitution? Other legal thinkers have explored whether a national “right to abortion” can be justified on originalist grounds.1 Assuming that it cannot, and that Roe v. Wade2 and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylva- nia v. Casey3 were wrongly decided, only two other options are available. Should preborn human beings be considered legal “persons” within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, or do states retain authority to make abortion policy? INTRODUCTION During initial arguments for Roe v. Wade, the state of Texas ar- gued that “the fetus is a ‘person’ within the language and mean- ing of the Fourteenth Amendment.”4 The Supreme Court rejected that conclusion. Nevertheless, it conceded that if prenatal “per- sonhood is established,” the case for a constitutional right to abor- tion “collapses, for the fetus’ right to life would then be guaran- teed specifically by the [Fourteenth] Amendment.”5 Justice Harry Blackmun, writing for the majority, observed that Texas could cite “no case . that holds that a fetus is a person within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.”6 1. See Antonin Scalia, God’s Justice and Ours, 156 L. & JUST. - CHRISTIAN L. REV. 3, 4 (2006) (asserting that it cannot); Jack M. Balkin, Abortion and Original Meaning, 24 CONST. COMMENT. 291 (2007) (arguing that it can). 2. 410 U.S. 113 (1973). 3. 505 U.S. 833 (1992). 4. Roe, 410 U.S. at 156. Strangely, the state of Texas later balked from the impli- cations of this position by suggesting that abortion can “be best decided by a [state] legislature.” John D. -

The Partisan Trajectory of the American Pro-Life Movement: How a Liberal Catholic Campaign Became a Conservative Evangelical Cause

Religions 2015, 6, 451–475; doi:10.3390/rel6020451 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article The Partisan Trajectory of the American Pro-Life Movement: How a Liberal Catholic Campaign Became a Conservative Evangelical Cause Daniel K. Williams Department of History, University of West Georgia, 1601 Maple St., Carrollton, GA 30118, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-678-839-6034 Academic Editor: Darren Dochuk Received: 25 February 2015 / Accepted: 3 April 2015 / Published: 16 April 2015 Abstract: This article employs a historical analysis of the religious composition of the pro-life movement to explain why the partisan identity of the movement shifted from the left to the right between the late 1960s and the 1980s. Many of the Catholics who formed the first anti-abortion organizations in the late 1960s were liberal Democrats who viewed their campaign to save the unborn as a rights-based movement that was fully in keeping with the principles of New Deal and Great Society liberalism, but when evangelical Protestants joined the movement in the late 1970s, they reframed the pro-life cause as a politically conservative campaign linked not to the ideology of human rights but to the politics of moral order and “family values.” This article explains why the Catholic effort to build a pro-life coalition of liberal Democrats failed after Roe v. Wade, why evangelicals became interested in the antiabortion movement, and why the evangelicals succeeded in their effort to rebrand the pro-life campaign as a conservative cause. Keywords: Pro-life; abortion; Catholic; evangelical; conservatism 1. -

Abortion: Judicial and Legislative Control

ABORTION: JU3ICIAL AND LEGISLATIVE CONTROL ISSUE BRIEF NUMEER IB74019 AUTHOR: Lewis, Karen J. American Law Division Rosenberg, Morton American Law Division Porter, Allison I. American Law Division THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE MAJOR ISSUES SYSTEM DATE ORIGINATED DATE UPDATED FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION CALL 287-5700 1013 CRS- 1 ISSUE DEFINITION In 1973 the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Constitution protects a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy, Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, and that a State may not unduly burden the exercise of that fundamental right by regulations that prohibit or substantially limit access to the means of effectuating that decision, Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179. But rather than settling the issue, the Court's rwlings have kindled heated debate and precipitated a variety of governmental actions at the national, State and local levels designed either to nullify the rulings or hinder their effectuation. These governmental regalations have, in turn, spawned further litigation in which resulting judicial refinements in the law have been no more successful in dampening the controversy. Thus the 97th Congress promises to again be a forum for proposed legislation and constitutional amendments aimed at limiting or prohibiting the practice of abortion and 1981 will see Court dockets, including that of the Supreme Court, filled with an ample share of challenges to5State and local actions. BACKGROUND AND POLICY ANALYSIS The background section of this issue brief is organized under five categories, as follows: I. JUDICIAL HISTORY A. Development and Status of the Law Prior to 1973 B.