Visual Representation in Death with Dignity Storytelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STUDY GUIDE Prepared by Maren Robinson, Dramaturg

by Susan Felder directed by William Brown STUDY GUIDE Prepared by Maren Robinson, Dramaturg This Study Guide for Wasteland was prepared by Maren Robinson and edited by Kerri Hunt and Lara Goetsch for TimeLine Theatre, its patrons and educational outreach. Please request permission to use these materials for any subsequent production. © TimeLine Theatre 2012 — STUDY GUIDE — Table of Contents About the Playwright ........................................................................................ 3 About the Play ................................................................................................... 3 The Interview: Susan Felder ............................................................................ 4 Glossary ............................................................................................................ 11 Timeline: The Vietnam War and Surrounding Historical Events ................ 13 The History: Views on Vietnam ...................................................................... 19 The Context: A New Kind of War and a Nation Divided .............................. 23 Prisoners of War and Torture ......................................................................... 23 Voices of Prisoners of War ............................................................................... 24 POW Code of Conduct ..................................................................................... 27 Enlisted vs. Drafted Soldiers .......................................................................... 28 The American -

Forty-Two Years and the Frequent Wind: Vietnamese Refugees in America

FORTY-TWO YEARS AND THE FREQUENT WIND: VIETNAMESE REFUGEES IN AMERICA Photography by Nick Ut Exhibition Curator: Randy Miller Irene Carlson Gallery of Photography August 28 through October 13, 2017 A reception for Mr. Ut will take place in the Irene Carlson Gallery of Photography, 5:00 – 6:00 p.m. Thursday, September 21, 2017 Nick Ut Irene Carlson Gallery of Photography FORTY-TWO YEARS AND THE FREQUENT WIND: August 28 – October 13, 2017 VIETNAMESE REFUGEES IN AMERICA About Nick Ut… The second youngest of 11 siblings, Huỳnh Công (Nick) Út, was born March 29, 1951, in the village of Long An in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. He admired his older brother, Huynh Thanh My, who was a photographer for Associated Press, and who was reportedly obsessed with taking a picture that would stop the war. Huynh was hired by the AP and was on assignment in 1965 when he and a group of soldiers he was with were overrun by Viet Cong rebels who killed everyone. Three months after his brother’s funeral, Ut asked his brother’s editor, Horst Faas, for a job. Faas was reluctant to hire the 15-year-old, suggesting he go to school, go home. “AP is my home now,” Ut replied. Faas ultimately relented, hiring him to process film, make prints, and keep the facility clean. But Ut wanted to do more, and soon began photographing around the streets of Saigon. "Then, all of a sudden, in 1968, [the Tet Offensive] breaks out," recalls Hal Buell, former AP photography director. "Nick had a scooter by then. -

(WALL NEWSPAPER PROJECT – Michelle) Examples of Investigative Journalism + Film

ANNEX II (WALL NEWSPAPER PROJECT – michelle) Examples of investigative journalism + film Best American Journalism of the 20th Century http://www.infoplease.com/ipea/A0777379.html The following works were chosen as the 20th century's best American journalism by a panel of experts assembled by the New York University school of journalism. 1. John Hersey: “Hiroshima,” The New Yorker, 1946 2. Rachel Carson: Silent Spring, book, 1962 3. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein: Investigation of the Watergate break-in, The Washington Post, 1972 4. Edward R. Murrow: Battle of Britain, CBS radio, 1940 5. Ida Tarbell: “The History of the Standard Oil Company,” McClure's, 1902–1904 6. Lincoln Steffens: “The Shame of the Cities,” McClure's, 1902–1904 7. John Reed: Ten Days That Shook the World, book, 1919 8. H. L. Mencken: Scopes “Monkey” trial, The Sun of Baltimore, 1925 9. Ernie Pyle: Reports from Europe and the Pacific during WWII, Scripps-Howard newspapers, 1940–45 10. Edward R. Murrow and Fred Friendly: Investigation of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, CBS, 1954 11. Edward R. Murrow, David Lowe, and Fred Friendly: documentary “Harvest of Shame,” CBS television, 1960 12. Seymour Hersh: Investigation of massacre by US soldiers at My Lai (Vietnam), Dispatch News Service, 1969 13. The New York Times: Publication of the Pentagon Papers, 1971 14. James Agee and Walker Evans: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, book, 1941 15. W. E. B. Du Bois: The Souls of Black Folk, collected articles, 1903 16. I. F. Stone: I. F. Stone's Weekly, 1953–67 17. Henry Hampton: “Eyes on the Prize,” documentary, 1987 18. -

Avatars De Napalm Girl, June 8, 1972 (Nick Ut) : Variations Autour D’Une Icône De La Guerre Du Vietnam Anne Lesme

Avatars de Napalm Girl, June 8, 1972 (Nick Ut) : variations autour d’une icône de la Guerre du Vietnam Anne Lesme To cite this version: Anne Lesme. Avatars de Napalm Girl, June 8, 1972 (Nick Ut) : variations autour d’une icône de la Guerre du Vietnam. E-rea - Revue électronique d’études sur le monde anglophone, Laboratoire d’Études et de Recherche sur le Monde Anglophone, 2015, “ Que fait l’image ? De l’intericonicité aux États-Unis ” / “What do Pictures Do? Intericonicity in the United States”, 10.4000/erea.4650. hal-01424237 HAL Id: hal-01424237 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01424237 Submitted on 2 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. E-rea Revue électronique d’études sur le monde anglophone 13.1 | 2015 1. « Que fait l'image ? De l'intericonicité aux États-Unis » / 2. « Character migration in Anglophone Literature » Avatars de Napalm Girl, June 8, 1972 (Nick Ut) : variations autour d’une icône de la Guerre du Vietnam Anne LESME Éditeur Laboratoire d’Études et de Recherche sur le Monde Anglophone Édition électronique URL : http://erea.revues.org/4650 ISBN : ISSN 1638-1718 Ce document vous est offert par Aix ISSN : 1638-1718 Marseille Université Référence électronique Anne LESME, « Avatars de Napalm Girl, June 8, 1972 (Nick Ut) : variations autour d’une icône de la Guerre du Vietnam », E-rea [En ligne], 13.1 | 2015, mis en ligne le 15 décembre 2015, consulté le 02 janvier 2017. -

JRNL 494.03: Pollner Seminar - Advanced Multimedia Storytelling

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Spring 9-2016 JRNL 494.03: Pollner Seminar - Advanced Multimedia Storytelling Sara (Sally) E. Stapleton University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Stapleton, Sara (Sally) E., "JRNL 494.03: Pollner Seminar - Advanced Multimedia Storytelling" (2016). Syllabi. 3855. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/3855 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADVANCED MULTIMEDIA STORYTELLING (The importance of the moment) In a nod to the Celia Cruz song “Rie y Llora” from the posthumous release of her “Regalo del Alma” collection a month after her death in 2003. The University of Montana School of Journalism J494 Pollner Seminar Spring 2016 Mondays and Wednesdays, 12:40 p.m. – 2 p.m. in 210 Don Anderson Hall Instructor: Sally Stapleton Office: 429 Don Anderson Hall Email: [email protected] Office number: 406-243-2256 Cell: 6464-246-7370 Twitter: @sestapleton Office hours: Tuesdays and Thursday, 1 p.m. – 3 p.m. but I’m flexible. I’ll spend hours at the Kaiman, so you might seek me out there. Send me an email to arrange something if it’s outside hours. We’ll need to meet periodically to make sure you’re making progress on the three projects due during the semester. -

Professor Karol Sikora

THE MAGAZINE FOR DULWICH COLLEGE ALUMNI FEATURING PROFESSOR KAROL SIKORA With reflections on the pandemic and its impact on cancer PLUS KYLE KARIM AT LEGO AND THE ORIGINS OF SOCCER AT DC WELCOME TO THE MAGAZINE FOR DULWICH COLLEGE ALUMNI PAGE 03 Meet the Team Trevor Llewelyn Matt Jarrett (72-79) Hon Secretary of Director of Development the Alleyn Club As I write this editorial the College is currently In the last edition of OA I hoped that our new format closed to all but the children of key workers. It is would allow us to look in greater depth at the only the third time in the school’s long history that lives and careers of OAs. That we have been able this has happened and two of those have been in to do with interviews with sailor Mark Richmond, response to Covid 19. The only other time our gates opera singer Rodney Clarke and Kyle Karim who Joanne Whaley have been shut was during the Second World War as Director of Marketing for Lego may, by his own Kathi Palitz when we temporarily moved out of the capital in admission, just have the best job in the world. Alumni & Parent Database and Operations order to share the facilities of Tonbridge School. It Relations Manager was not a success and the boys soon returned to Like much of the country very little competitive sport Manager London and in so doing Dulwich became one of the took place during the summer and our reporting very few public schools not to be evacuated for the reflects this. -

War, Women, Vietnam: the Mobilization of Female Images, 1954-1978

War, Women, Vietnam: The Mobilization of Female Images, 1954-1978 Julie Annette Riggs Osborn A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: William J. Rorabaugh, Chair Susan Glenn Christoph Giebel Program Authorized to Offer Degree: History ©Copyright 2013 Julie Annette Riggs Osborn University of Washington Abstract War, Women, Vietnam: The Mobilization of Female Images, 1954-1978 Julie Annette Riggs Osborn Chair of the Supervisory Committee: William J. Rorabaugh, History This dissertation proceeds with two profoundly interwoven goals in mind: mapping the experience of women in the Vietnam War and evaluating the ways that ideas about women and gender influenced the course of American involvement in Vietnam. I argue that between 1954 and 1978, ideas about women and femininity did crucial work in impelling, sustaining, and later restraining the American mission in Vietnam. This project evaluates literal images such as photographs, film and television footage as well as images evoked by texts in the form of news reports, magazine articles, and fiction, focusing specifically on images that reveal deeply gendered ways of seeing and representing the conflict for Americans. Some of the images I consider include a French nurse known as the Angel of Dien Bien Phu, refugees fleeing for southern Vietnam in 1954, the first lady of the Republic of Vietnam Madame Nhu, and female members of the National Liberation Front. Juxtaposing images of American women, I also focus on the figure of the housewife protesting American atrocities in Vietnam and the use of napalm, and images wrought by American women intellectuals that shifted focus away from the military and toward the larger social and psychological impact of the war. -

Special 75Th Anniversary Issue

NIEMAN REPORTS SUMMER/FALL 2013 VOL. 67 NO. 2-3 Nieman Reports The Nieman Foundation for Journalism Harvard University One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 VOL. 67 NO. 2-3 SUMMER-FALL 2013 TO PROMOTE AND ELEVATE THE STANDARDS OF JOURNALISM 75 TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY Special 75th Anniversary Issue Agnes Wahl Nieman The Faces of Agnes Wahl Nieman About the cover: British artist Jamie Poole (left) based his portrait of Agnes Wahl Nieman on one of only two known images of her—a small engraving from a collage published in The Milwaukee Journal in 1916—and on the physical description she provided in her 1891 passport application: light brown hair, bluish-gray eyes, and fair complexion. Using portraits of Mrs. Nieman’s mother and father as references, he worked with cut pages from Nieman Reports and from the Foundation’s archival material to create this likeness. About the portrait on page 6: Alexandra Garcia (left), NF ’13, an Emmy Award-winning multimedia journalist with The Washington Post, based her acrylic portrait with collage on the photograph of Agnes Wahl Nieman standing with her husband, Lucius Nieman, in the pressroom of The Milwaukee Journal. The photograph was likely taken in the mid-1920s when Mrs. Nieman would have been in her late 50s or 60s. Garcia took inspiration from her Fellowship and from the Foundation’s archives to present a younger depiction of Mrs. Nieman. Video and images of the portraits’ creation can be seen at http://nieman.harvard.edu/agnes. A Nieman lasts a year ~ a Nieman lasts a lifetime SUMMER/FALL 2013 VOL. -

Current Developments in Federal Indian Law

Current Developments in Federal Indian Law Cosponsored by the Indian Law Section Friday, September 15, 2017 9 a.m.–5 p.m. 6.5 General CLE or Access to Justice credits CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS IN FEDERAL INDIAN LAW SECTION PLANNERS Diana Jean Bettles, Attorney at Law, Klamath Falls, OR Diane Henkels, Attorney at Law, Newport, OR Nathan Karman, Oregon Department of Justice, Portland, OR Stephen Kelly, NW Natural, Portland, OR Douglas MacCourt, Senior Counsel, Rosette LLP, Washington, DC Holly Partridge, The Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon, Grand Ronde, OR Suzanne Trujillo, Office of Legislative Counsel, Salem, OR Cathern Tufts, Attorney at Law, Siletz, OR Jessie Young, Department of the Interior, Office of the Regional Solicitor, Portland, OR OREGON STATE BAR INDIAN LAW SECTION EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Diane Henkels, Chair Nathan A. Karman, Chair-Elect Anthony Stephen Broadman, Past Chair Jessie D. Young, Treasurer Todd Albert, Secretary Kristy Kay Barrett Diana Jean Bettles Jennifer Biesack Sarah Rose Dandurand Stephen P. Kelly Douglas C. MacCourt Holly Ray Partridge Stephanie L. Striffler Patrick Sullivan Cathern E. Tufts Kristen L. Winemiller The materials and forms in this manual are published by the Oregon State Bar exclusively for the use of attorneys. Neither the Oregon State Bar nor the contributors make either express or implied warranties in regard to the use of the materials and/or forms. Each attorney must depend on his or her own knowledge of the law and expertise in the use or modification of these materials. Copyright © 2017 OREGON STATE BAR 16037 SW Upper Boones Ferry Road P.O. -

Unplug-Issue-26.Pdf

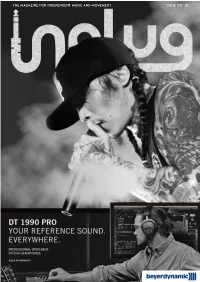

THE MAGAZINE FOR INDEPENDENT MUSIC AND MOVEMENT ISSUE NO. 26 ISSUE NO. 26 @UNPLUGMAGAZINE BEYOND THE SCENE 4 IAN TAYAO BEHIND THE SCENE 11 YOKAI - SAYDIE INDIEZONE 14 MAY ARTISTS 23 WARNER CORNER MARYZARK PHOTOGRAPHY 36 DADDY RAKISTA ARTIST/GEARS 40 CHAMPAGNE DRIVE DJ SCENE 44 ZEDD, CLASSIXX and more! GAMES 55 FORTNITE, PUBG TUBE 57 FEATURED MV MUSIC EVENT PRODUCTION 59 feat. SOUTHCREW PRODUCTION www.facebook.com/UnplugMagazine www.caeditorial.com/Unplug Disclaimer: All rights reserved. No part of this publication or content may be reproduced or used without the written permission of the publisher: C.A. Editorial Consultants. All information contained in this magazine is for information only, and is, as far as we are aware, correct at the time of going to press. The views, ideas, comments, and opinions expressed in this publication are solely of the writers, interviewees, press agencies, and manufacturers and do not represent the views of the editors or the publisher. Whilst every care is taken to ensure the accuracy and honesty in both editorial and advertising content at press time, the publisher will not be liable for any inaccuracies or losses incurred. Readers are advised to contact manufacturers and retailers directly with regard to the price of products/services referred to in this publication. If you submit material to us, you automatically grant C.A. Editorial Consultants a license to publish your submission in whole or in part in all editions of the magazine, including licensed editions worldwide and in any physical or digital format throughout the world. THE TEAM 3 WRITERS AHMAD TANJI AIMAX MACOY ALFIE VERA MELLA ANDREW G. -

IMMF 13 Bios Photogs.Pdf (188

Index of photographers and artists with lot numbers and short biographies Anderson, Christopher (Canada) - Born in British Columbia 1971). He had been shot in the back of the head. in 1970, Christopher Anderson also lived in Texas and Colorado In Lots 61(d), 63 (d), 66(c), 89 and NYC. He now lives in Paris. Anderson is the recipient of the Robert Capa Gold Medal. He regularly produces in depth photographic projects for the world’s most prestigious publica- Barth, Patrick (UK) Patrick Barth studied photography at tions. Honours for his work also include the Visa d’Or in Newport School of Art & Design. Based in London, he has been Perpignan, France and the Kodak Young Photographer of the working since 1995 as a freelance photographer for publications Year Award. Anderson is a contract photographer for the US such as Stern Magazine, the Independent on Sunday Review, News & World Report and a regular contributor to the New Geographical Magazine and others. The photographs in Iraq York Times Magazine. He is a member of the photographers’ were taken on assignment for The Independent on Sunday collective, VII Agency. Review and Getty Images. Lot 100 Lot 106 Arnold, Bruno (Germany) - Bruno Arnold was born in Bendiksen Jonas (Norway) 26, is a Norwegianp photojournal- Ludwigshafen/Rhine (Germany) in 1927. Journalist since 1947, ist whose work regularly appears in magazines world wide from 1955 he became the correspondent and photographer for including GEO, The Sunday Times Magazine, Newsweek, and illustrated magazines Quick, Revue. He covered conflicts and Mother Jones. In 2003 Jonas received the Infinity Award from revolutions in Hungary and Egypt (1956), Congo (1961-1963), The International Centre of Photography (ICP) in New York, as Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos (1963-1973), Biafra (1969-1070), well as a 1st prize in the Pictures Of the Year International Israel (1967, 1973, 1991, 1961 Eichmann Trial). -

Ideological, Dystopic, and Antimythopoeic Formations of Masculinity in the Vietnam War Film Elliott Stegall

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Ideological, Dystopic, and Antimythopoeic Formations of Masculinity in the Vietnam War Film Elliott Stegall Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IDEOLOGICAL, DYSTOPIC, AND ANTIMYTHOPOEIC FORMATIONS OF MASCULINITY IN THE VIETNAM WAR FILM By ELLIOTT STEGALL A Dissertation submitted to the Program in Interdisciplinary Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2014 Elliott Stegall defended this dissertation on October 21, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: John Kelsay Professor Directing Dissertation Karen Bearor University Representative Kathleen Erndl Committee Member Leigh Edwards Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful for my wife, Amanda, whose love and support has made all of this possible; for my mother, a teacher, who has always been there for me and who appreciates a good conversation; to my late father, a professor of humanities and religion who allowed me full access to his library and record collection; and, of course, to the professors who have given me their insight and time. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures................................................................................................................................. v Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………...... vi 1. VIETNAM MOVIES, A NEW MYTHOS OF THE MASCULINE......................................... 1 2. DISPELLING FILMIC MYTHS OF THE VIETNAM WAR……………………………... 24 3. IN DEFENSE OF THE GREEN BERETS ……………………………………………….....