Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kuwaittimes 8-12-2019.Qxp Layout 1

RABIA ALTHANI 11, 1441 AH SUNDAY, DECEMBER 8, 2019 28 Pages Max 19º Min 12º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 18004 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Indian police probed over Al Mulla Group partners ‘Laugh at what’s hurting you’: Filipina sprinter takes 200m 6 killings of rape suspects 13 with XCMG Group 24 Lebanon cartoonists stir debate 28 crown from ‘Queen of Speed’ Qatari minister talks of ‘some progress’ in mending Gulf rift FM lauds Kuwait Amir’s efforts, commitment to resolve differences DOHA: Qatar’s foreign minister has spoken of “some place under Kuwaiti mediation and thanked HH the Amir progress” in talks with Saudi Arabia on ending a bitter Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah for his “con- two-year-old rift between Doha and the kingdom and its tinuous efforts and commitment”. allies. A Saudi-led bloc including the United Arab The disclosure of talks come shortly after Saudi King Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt cut all diplomatic and trans- Salman invited Qatar’s amir to a summit of the Gulf port ties with Qatar in June 2017. They broke with Doha regional bloc in Riyadh on Tuesday. Observers are eagerly over allegations it backs radical Islamists and seeks closer awaiting Qatar’s response, which could pave the way for a ties with Saudi arch rival Iran. Qatar vehemently denies “reconciliation conference” despite the many hurdles that the charges. obstruct the path to detente. “Signs that a reconciliation is In the latest sign of a thaw, Qatari Foreign Minister impending are multiplying,” Kristian Ulrichsen, a fellow at Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al-Thani said Friday there Rice University’s Baker Institute in the United States, said had been “some progress” in talks with Saudi Arabia. -

Esf-2018-Brochure-300717.Pdf

IAN WRIGHT THE UK’S BIGGEST YOUTH FOOTBALL FESTIVAL THE GREATEST WEEKEND IN YOUTH FOOTBALL CONTENTS ABOUT ESF 4 ESF 2018 CALENDAR 7 CELEBRITY PRESENTATIONS 8 ESF GRAND FINALE 10 GIRLS FOOTBALL AT ESF 12 BUTLIN’S BOGNOR REGIS 14 BUTLIN’S MINEHEAD 16 BUTLIN’S SKEGNESS 18 HAVEN AYR 20 2017 ROLL OF HONOUR 22 TESTIMONIALS 24 FESTIVAL INFO, T&C’s 26 TEAM REGISTRATION FORM 29 AYR 6 - 9 April 4 - 7 May SKEGNESS ESF FINALE 20 - 23 April 7 - 8 July 4 - 7 May MINEHEAD 27 - 30 April BOGNOR REGIS 4 - 7 May 18 - 21 May Search ESF Festival of Football T 01664 566360 E [email protected] W www.footballfestivals.co.uk 3 THE ULTIMATE TOUR WAYNE BRIDGE, CASEY STONEY & SUE SMITH THE UK’S BIGGEST YOUTH FOOTBALL FESTIVAL With 1200 teams and 40,000 people participating, ESF is the biggest youth football festival in the UK. There’s nowhere better to take your team on tour! THE ULTIMATE TOUR TOUR ESF is staged exclusively at Butlin’s award winning Resorts in Bognor Regis, Minehead and Skegness, and Haven’s Holiday Park in Ayr, Scotland. Whatever the result on the pitch, your team are sure to have a fantastic time away together on tour. CELEBRITY ROBERT PIRES PRESENTATIONS Our spectacular presentations are always a tour highlight. Celebrity guests have included Robert Pires, Kevin Keegan, Wayne Bridge, Stuart Pearce, Casey Stoney, Sue Smith, Robbie Fowler, Ian Wright, Danny Murphy and more. ESF GRAND FINALE AT ST GEORGE’S PARK Win your age section at ESF 2018 and your team will qualify for the prestigious ESF Grand Finale, our Champion of Champions event. -

Wimbledon FC to Milton Keynes This Summer Is a Critical Moment in London’S Football History

Culture, Sport and Tourism Away from home Scrutiny of London’s Football Stadiums June 2003 Culture, Sport and Tourism Away from home Scrutiny of London’s Football Stadiums June 2003 copyright Greater London Authority June 2003 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 1 85261 496 1 Cover photograph credit EMPICS Sports Photo Agency This publication is printed on recycled paper Chair’s Foreword The move by Wimbledon FC to Milton Keynes this summer is a critical moment in London’s football history. This move prompted the London Assembly’s Culture, Sport and Tourism committee to look into the issue of redevelopment for London clubs. With Fulham and Brentford yet to secure new stadiums for their clubs and question marks remaining over Arsenal’s and Tottenham’s grounds the issue is a live one. We do not want to see more clubs leave London. During the 2002/03 season about 5 million fans watched professional football in London. In addition, hundreds of thousands of Londoners participate every year in club sponsored community projects and play football. This report seeks to ensure that this added value isn’t lost to Londoners. We did not set out to judge local situations but to tease out lessons learnt by London football clubs. Football is more than just a business: the ties that a club has with its area and the fans that live or come from there are great. We recommend that more clubs have supporters on their board and applaud the work of Supporters Direct in rejuvenating the links between clubs and their fan base. -

White Hart Lane Legends Volume One

WHITE HART LANE LEGENDS VOLUME ONE Tottenham shirt. Apart from the fans, the Spurs logo is the most treasured asset of the club. It should be marketed to a wider audience and pushed in the same way that Manchester United did with theirs. Arsenal winning the League does our cause untold damage. Do you think it’s the same for the players? Seriously, I’ve actually got a very high regard for Paul Merson for his loyalty to Arsenal. He was apparently offered the chance to go to White Hart Lane twice and turned it down because of his love and affection for the Highbury outfit and their fans. I’m the same. Once a Spurs man, always a Spurs man in my book and I just couldn’t be seen in red. Crossing the great divide is not an option. I just can’t understand why anybody would want to do it. Tell me about ‘that’ tackle on Charlie Nicholas? To be honest, I actually saw it as more of an accidental nudge, but his momentum took him high and fast over a hoarding. It looked much worse than was actually intended, and to be fair, it was Tottenham versus Arsenal at Highbury, not some Mickey Mouse game that didn’t matter [smiles]. Given the same situation now, I’d probably challenge the same way as I did then, although the funny thing about it was getting punished twice. As Charlie ran towards the ball I slid in to dispossess him, then ended up on the ground. Their physio ran over to me, landed on top and proceeded to punch me in the face. -

Season 2017-18 SWINDON LONDON GLASGOW

0033 RRoyaloyal WWoottonootton WWindsorindsor 22017-18017-18 BBassettassett TownTown FF.C..C. FF.C..C. Played Played Home Team SquadNo. Sub Visitors Team Squad No. Sub 1 Matt Bulman 1 Hugo Sobte 2 Aaron Stevens 2 Remmel Clarke 3 Dale Richards 3 Haydon Clarke 4 Kai Robinson 4 Jack Denton 5 Matt Cheetham 5 Andrew Ingram 6 Ben Lodge 6 Luke Brooks-Smith 7 Mason Thompson 7 Taufee Skandari 8 Giorgio Wrona 8 Ashley Smith 9 Dave Coleman 9 Barry Hayles 10 Nathan Gambling 10 Paul Coyne 11 Sam Packer 11 Gus Bowles 12 Steve Yeardley 12 Tommy Williams 14 George Drewitt 14 Jon Case 15 Jonny Aitkenhead 15 Charlie Dean 16 Callum Wright 16 Justin Koeries 17 Nathan Hawkins 17 Nadir Shafi 18 Dan Bailey 18 19 Ryan Rawlins 19 20 George Lance 20 21 Chris Jackson 21 22 Bradley Clarke 22 23 Daniel Lawrence 23 24 Levi Cox 24 25 Adam Corcoran 25 26 26 27 27 28 28 Dugout Team Dugout Team Manager:Rich Hunter Manager: Mick Woodham Assistant:Chris Green Assistant: Ashley Smith Coaches:Sam Collier & Mike Brewer Coach: Craig Turner SSeasoneason 22017-18017-18 Therapist:Kara Gregory Physio: Simone Connor Match Officials Referee: Luke Peacock Assist. Ref (Red Flag): Derek Pinchen Uhlsport Hellenic League Premier Division Assist. Ref (Yellow Flag): Calli Smith Next Home Games RRoyaloyal WWoottonootton BBassettassett TTownown Tue 22-Aug-17 v Marlborough Town (Wiltshire Senior League) Kick-off 7.00PM Sat 26-Aug-17 v Thatcham Town (Uhlsport Hellenic League Premier Division) Kick-off 3.00PM v WWindsorindsor KKeepeep uuptopto ddateate wwithith tthehe TTownown oonn FFacebookacebook oorr SSaturdayaturday 119th9th AAugustugust 22017017 TTwitter,witter, oorr vvisitisit tthehe CClub’slub’s wwebsiteebsite aatt NNewew GGerarderard BBuxtonuxton GGround,round, KKick-offick-off 33.00PM.00PM wwww.rwbtfc.co.ukww.rwbtfc.co.uk OOfffi ccialial MMatchatch DDayay PProgrammerogramme ££1.501.50 Club Offi cials Season 2017-18 SWINDON LONDON GLASGOW (founded 1882) Royal Wootton Bassett Town F.C. -

Turnham Classes

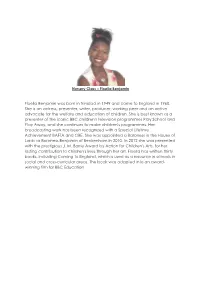

Nursery Class – Floella Benjamin Floella Benjamin was born in Trinidad in 1949 and came to England in 1960. She is an actress, presenter, writer, producer, working peer and an active advocate for the welfare and education of children. She is best known as a presenter of the iconic BBC children's television programmes Play School and Play Away, and she continues to make children's programmes. Her broadcasting work has been recognized with a Special Lifetime Achievement BAFTA and OBE. She was appointed a Baroness in the House of Lords as Baroness Benjamin of Beckenham in 2010. In 2012 she was presented with the prestigious J. M. Barrie Award by Action for Children's Arts, for her lasting contribution to children's lives through her art. Floella has written thirty books, including Coming to England, which is used as a resource in schools in social and cross-curricular areas. The book was adapted into an award- winning film for BBC Education Trish Cooke – Reception Trish Cooke is a British playwright, actress, television presenter and award-winning children’s author. She was born in Bradford, Yorkshire. Her parents are from Dominica in the West Indies. She comes from a large family, with six sisters, three brothers, eight nephews, six nieces, three great-nieces and one great-nephew, all of whom provide her with the inspiration for her picture books. One of her most successful books is called ‘So Much’, which is a joyful celebration of family life. She is known by many from her days presenting the preschool BBC programme Playdays. -

1985 NSCAA New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Cedarville College

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Men's Soccer Programs Men's Soccer Fall 1985 1985 NSCAA New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ mens_soccer_programs Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons This Program is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Men's Soccer Programs by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1985 NSCAA/New Balance All-America Awards Banquet National Soccer Coaches Association of America Saturday, January 18, 1986 Sheraton - St. Louis Hotel St. Louis, Missouri Dear All-America Performer, Congratulations on being selected as a recipient of the National Soccer Coaches Association of America/New Balance All-America Award for 1985. Your selection as one of the top performers in the Gnited States is a tribute to your hard work, sportsmanship and dedication to the sport of soccer. All of us at New Balance are proud to be associated with the All-America Awards and look forward to presenting each of you with a separate award for your accomplishment. Good luck in your future endeavors and enjoy your stay in St. Louis. Sincerely, James S. Davis President new balance8 EXCLUSIVE SPONSOR OF THE NSCAA/NEW BALANCE ALL-AMERICA AWARDS Program NSCAA/New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Master of Cerem onies............................. William T. Holleman, Second Vice-President, NSCAA The Lovett School, Georgia Invocation.................................... ....................................................................... Whitney Burnham Dartmouth College NSCAA All-America Awards Youth Girl’s and Boy’s T ea m s............................................................................. -

Silva: Polished Diamond

CITY v BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 | £3.00 PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY SILVA: POLISHED DIAMOND 38008EYEU_UK_TA_MCFC MatDay_210x148w_Jan17_EN_P_Inc_#150.indd 1 21/12/16 8:03 pm CONTENTS 4 The Big Picture 52 Fans: Your Shout 6 Pep Guardiola 54 Fans: Supporters 8 David Silva Club 17 The Chaplain 56 Fans: Junior 19 In Memoriam Cityzens 22 Buzzword 58 Social Wrap 24 Sequences 62 Teams: EDS 28 Showcase 64 Teams: Under-18s 30 Access All Areas 68 Teams: Burnley 36 Short Stay: 74 Stats: Match Tommy Hutchison Details 40 Marc Riley 76 Stats: Roll Call 42 My Turf: 77 Stats: Table Fernando 78 Stats: Fixture List 44 Kevin Cummins 82 Teams: Squads 48 City in the and Offi cials Community Etihad Stadium, Etihad Campus, Manchester M11 3FF Telephone 0161 444 1894 | Website www.mancity.com | Facebook www.facebook.com/mcfcoffi cial | Twitter @mancity Chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak | Chief Executive Offi cer Ferran Soriano | Board of Directors Martin Edelman, Alberto Galassi, John MacBeath, Mohamed Mazrouei, Simon Pearce | Honorary Presidents Eric Alexander, Sir Howard Bernstein, Tony Book, Raymond Donn, Ian Niven MBE, Tudor Thomas | Life President Bernard Halford Manager Pep Guardiola | Assistants Rodolfo Borrell, Manel Estiarte Club Ambassador | Mike Summerbee | Head of Football Administration Andrew Hardman Premier League/Football League (First Tier) Champions 1936/37, 1967/68, 2011/12, 2013/14 HONOURS Runners-up 1903/04, 1920/21, 1976/77, 2012/13, 2014/15 | Division One/Two (Second Tier) Champions 1898/99, 1902/03, 1909/10, 1927/28, 1946/47, 1965/66, 2001/02 Runners-up 1895/96, 1950/51, 1988/89, 1999/00 | Division Two (Third Tier) Play-Off Winners 1998/99 | European Cup-Winners’ Cup Winners 1970 | FA Cup Winners 1904, 1934, 1956, 1969, 2011 Runners-up 1926, 1933, 1955, 1981, 2013 | League Cup Winners 1970, 1976, 2014, 2016 Runners-up 1974 | FA Charity/Community Shield Winners 1937, 1968, 1972, 2012 | FA Youth Cup Winners 1986, 2008 3 THE BIG PICTURE Celebrating what proved to be the winning goal against Arsenal, scored by Raheem Sterling. -

Review of 2010/11 – Part 2 – Losing Their Way

Review of 2010/11 – Part 2 – Losing their way Leeds United’s return to the Championship had seen them exceed expectations, despite heavy defeats at home to Preston and Cardiff and an embarrassing 5-2 reverse at Barnsley. The sheen of beating table-topping QPR on 18 December had been dulled by losing two-goal leads against Leicester and Portsmouth, but as 2011 opened, Leeds were fourth in the table, level on 40 points with Cardiff and Swansea, with Rangers seven points clear of that pack. It was heady stuff after three years in the League One wilderness and supporters were hopeful of a real promotion push in the New Year. Andy O'Brien, pictured celebrating his goal against Hull City on 9 November, made his move to Elland Road permanent on New The positive mood was enhanced by the Year's Day announcement that Irish international centre-back Andy O’Brien, on loan from Bolton since 29 October, would make the move permanent. O’Brien, who represented himself in contract talks, commented: “The meeting with the chairman was something I will remember all my life. It was a bit like when I signed my first contract at Bradford with Geoffrey Richmond – that was entertaining as well. My Dad came in with me initially and he is a big bloke of around 20 stone. The chairman’s first words were, ‘We’ll sign the fat one instead.’ My Dad replied he had been on a diet for six weeks, to which the chairman said, ‘Well that isn't effing working, is it?’ Dad is quite quick-witted and said back, ‘Well I don’t know what your excuse is’. -

Please Note We Do Not Accept Debit Or Credit Card Payments

Sporting Memorys Worldwide Auctions Ltd 11 Rectory Gardens, Castle Bromwich, Birmingham, B36 9DG Tel: 0121 684 8282 Fax: 0121 285 2825 E-Mail: [email protected] Welcome to our 25th Live Auction of Football & Sporting Memorabilia On Tuesday 8th & Wednesday 9th August 2017, 12.00pm start both days At Holy Souls Social Club, Acocks Green, Birmingham PLEASE NOTE WE DO NOT ACCEPT DEBIT OR CREDIT CARD PAYMENTS. TERMS & CONDITIONS Please see following page for full terms and conditions of the sale. AUCTIONEERS The guest Auctioneers are Mr Trevor Vennett-Smith and Mr Tim Davidson, the directors of Sporting Memorys W.A. Ltd, would all like to record their appreciation for their help and guidance. REGISTRATION It is requested that all clients should register before viewing in order to obtain a bidding paddle. VIEWING If you require further information, a photocopy or a scan of any lot then please do not hesitate to contact us as soon as possible. Tuesday 8th August 2017 - At Sale Room, 10.30am until 4.00pm* viewing for Day 1 finishes at 12.00pm Wednesday 9th August 2017 - At Sale Room, 8.30am until 11.45am COMMISSION BIDDING Will be accepted by Letters to Sporting Memorys W.A. Ltd, Telephone, Fax, or Email. PLEASE NOTE COMMISSION BIDS LEFT VIA THE-SALEROOM.COM ATTRACT EXTRA COMMISSION AS BELOW. Live Telephone Bidding must be arranged with Sporting Memorys W.A. Ltd as soon as possible. BUYERS COMMISSION Will be charged at 18% of the hammer price of all lots. In addition to this V.A.T. at 20% will be charged on the commission only, on standard rate items only. -

Weekly Bullentin

Network Activity Bulletin Week Commencing Saturday 15 July 2017 Network Activity Bulletin Contact Week Commencing Saturday 15 July 2017 Location Status Start Date End Date Details Promoter Works Contact Name Number CLOSURES - Hammersmith Flyover and A4 Westbound Only - 05.00 - 14.30. BOROUGH WIDE EVENT - Prudential Ride Prudential Ride London - For information please visit: Putney Bridge Southbound - 07.00 - 19.30. Proposed 30/07/2017 30/07/2017 Event Road Closure Michael Allen 020 87532480 //tfl.gov.uk/prudentialridelondon London New Kings Road both directions 07.00 - 19.30 UK Power o/sThe Novatel Proposed 31/07/2017 04/08/2017 Install HV cables in footway and carriageway Lane Closure Janet Nairne 020 87533115 Butterwick Networks (EDF) Bishops Park Road, Finlay Street, Fulham Proposed 29/07/2017 29/07/2017 PRE-SEASON FRIENDLY - Kick Off - Time to be confirmed Event Road Closure Janet Nairne 020 87533115 Craven Cottage Stadium - Fulham FC Palace Road & Stevenage Road Bishops Park Road, Finlay Street, Fulham Proposed 05/08/2017 05/08/2017 Kick Off - 15.00 Event Road Closure Janet Nairne 020 87533115 Craven Cottage Stadium - Fulham FC Palace Road & Stevenage Road Bishops Park Road, Finlay Street, Fulham Proposed 19/08/2017 19/08/2017 Kick Off - 15.00 Event Road Closure Janet Nairne 020 87533115 Craven Cottage Stadium - Fulham FC Palace Road & Stevenage Road Bishops Park Road, Finlay Street, Fulham Proposed 09/09/2017 09/09/2017 Kick Off - 15.00 Event Road Closure Janet Nairne 020 87533115 Craven Cottage Stadium - Fulham FC Palace Road & -

Premier League, 2018–2019

Premier League, 2018–2019 “The Premier League is one of the most difficult in the world. There's five, six, or seven clubs that can be the champions. Only one can win, and all the others are disappointed and live in the middle of disaster.” —Jurgen Klopp Hello Delegates! My name is Matthew McDermut and I will be directing the Premier League during WUMUNS 2018. I grew up in Tenafly, New Jersey, a town not far from New York City. I am currently in my junior year at Washington University, where I am studying psychology within the pre-med track. This is my third year involved in Model UN at college and my first time directing. Ever since I was a kid I have been a huge soccer fan; I’ve often dreamed of coaching a real Premier League team someday. I cannot wait to see how this committee plays out. In this committee, each of you will be taking the helm of an English Football team at the beginning of the 2018-2019 season. Your mission is simple: climb to the top of the world’s most prestigious football league, managing cutthroat competition on and off the pitch, all while debating pressing topics that face the Premier League today. Some of the main issues you will be discussing are player and fan safety, competition with the world’s other top leagues, new rules and regulations, and many more. If you have any questions regarding how the committee will run or how to prepare feel free to email me at [email protected].