Capitolo Tesi Def

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R Stern Phd Diss 2009

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Navigating the Boundaries of Political Tolerance: Environmental Litigation in China Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3rc0h094 Author Stern, Rachel E. Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Navigating the Boundaries of Political Tolerance: Environmental Litigation in China by Rachel E. Stern A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kevin J. O’Brien, Chair Professor Robert Kagan Professor Katherine O’Neill Fall 2009 Navigating the Boundaries of Political Tolerance: Environmental Litigation in China © 2009 by Rachel E. Stern Abstract Navigating the Boundaries of Political Tolerance: Environmental Litigation in China by Rachel E. Stern Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Kevin J. O’Brien, Chair This is a dissertation about lawyers, judges, international NGOs and legal action in an authoritarian state. The state is contemporary China. The type of legal action is civil environmental lawsuits, as when herdsmen from Inner Mongolia sue a local paper factory over poisoned groundwater and dead livestock or a Shandong villager demands compensation from a nearby factory for the noise that allegedly killed 26 foxes on his farm. Empirically, this is a close-to-the-ground account of everyday justice and the factors that shape it. Drawing on fifteen months of field research in China, along with in-depth exploration of four cases, legal documents, government reports, newspaper articles and blog archives, this dissertation unpacks how law as litigation works: how judges make decisions, why lawyers take cases and how international influence matters. -

The Impact of China's 1989 Tiananmen Massacre

The Impact of China’s 1989 Tiananmen Massacre The 1989 pro-democracy movement in China constituted a huge challenge to the survival of the Chinese communist state, and the efforts of the Chinese Communist party to erase the memory of the massacre testify to its importance. This consisted of six weeks of massive pro-democracy demonstrations in Beijing and over 300 other cities, led by students, who in Beijing engaged in a hunger strike which drew wide public support. Their actions provoked repression from the regime, which – after internal debate – decided to suppress the movement with force, leading to a still-unknown number of deaths in Beijing and a period of heightened repression throughout the country. This book assesses the impact of the movement, and of the ensuing repression, on the political evolution of the People’s Republic of China. The book discusses what lessons the leadership learned from the events of 1989, in particular whether these events consolidated authoritarian government or facilitated its adaptation towards a new flexibility which may, in time, lead to the transformation of the regime. It also examines the impact of 1989 on the pro-democracy movement, assessing whether its change of strategy since has consolidated the movement, or if, given the regime’s success in achieving economic growth and raising living standards, it has become increasingly irrelevant. It also examines how the repression of the movement has affected the economic policy of the Party, favoring the development of large State Enterprises and provoking an impressive social polarisation. Finally, Jean-Philippe Béja discusses how the events of 1989 are remembered and have affected China’s international relations and diplomacy; how human rights, law enforcement, policing, and liberal thought have developed over two decades. -

A Study of Judges' and Lawyers' Blogs In

Copyright © 2011 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. 2011 / Exercising Freedom of Speech behind the Great Firewall 251 reminding both of them of the significance of law, the legal and political boundaries set by the authorities are being pushed, challenged, and renegotiated. Drawing on existing literature on boundary contention and the Chinese cultural norm of fencun (decorum), this study highlights the paradox of how one has to fight within boundaries so as to expand the contours of the latter for one’s ultimate freedom. Judging from the content of the collected postings, one finds that, in various degrees, critical voices can be tolerated. What emerges is a responsive and engaging form of justice which endeavors to address grievances in society, and to resolve them in unique ways both online and offline. I. INTRODUCTION The Internet is a fascinating terrain. Much literature has been devoted to depicting its liberating democratic power in fostering active citizenry, and arguably, an equal number of articles have been written that describe attempts by various states to exercise control.1 China has provided a ready example to illustrate this tension. 2 And this study focuses on the blog postings by judges and public interest lawyers in order to understand better how the legal elites in China have deployed routine and regular legal discussion in the virtual world to form their own unique public sphere, not only as an assertion for their own autonomy but also as a subtle yet powerful form of contention against the legal and political boundaries in an authoritarian state. Chinese authorities are notorious for their determination to stamp out dissenting voices both online and offline. -

Resolving Constitutional Disputes in Contemporary China

Resolving Constitutional Disputes in Contemporary China Keith Hand* Beginning in 1999, a series of events generated speculation that the Chinese Party-state might be prepared to breathe new life into the country’s long dormant constitution. In recent years, as the Party-state has strictly limited constitutional adjudication and moved aggressively to contain some citizen constitutional activism, this early speculation has turned to pessimism about China’s constitutional trajectory. Such pessimism obscures recognition of alternative or hybrid pathways for resolving constitutional disputes in China. Despite recent developments, Chinese citizens have continued to constitutionalize a broad range of political-legal disputes and advance constitutional arguments in a variety of forums. This article argues that by shifting focus from the individual legal to the collective political dimension of constitutional law, a dimension dominant in China’s transitional one-party state, we can better understand the significance of the constitution in China and identify patterns of bargaining, consultation, and mediation across a range of both intrastate and citizen-state constitutional disputes. Administrative reconciliation and “grand mediation,” dispute resolution models at the core of recent political-legal shifts in China, emphasize such consultative practices. This zone of convergence reveals a potential transitional path * Associate Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law. Former Beijing Director and Senior Fellow, The China Law Center, Yale Law School (2005–2008) and Senior Counsel, U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China (2002–2005). The author thanks Donald Clarke, Michael Dowdle, Bruce Hand, Nicholas Howson, Hilary Josephs, Chimène Keitner, Tom Kellogg, Evan Lee, Benjamin Liebman, Lin Xifen, Carl Minzner, Randall Peerenboom, Zhang Qianfan, colleagues at the UC Hastings Junior Faculty Workshop, and members of the Chinalaw List for their thoughtful comments and feedback on drafts of the article. -

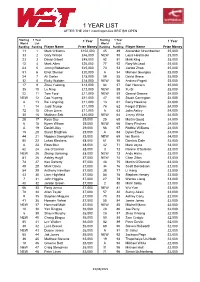

Master Money List After 2021 British Open.Xlsx

1 YEAR LIST AFTER THE 2021 matchroom.live BRITISH OPEN Starting 1 Year 1 YearStarting 1 Year 1 Year World List World List Ranking Ranking Player Name Prize MoneyRanking Ranking Player Name Prize Money 11 1 Mark Williams £102,000 45 49 Alexander Ursenbacher £5,000 33 2 Gary Wilson £46,000 NEW 50 Louis Heathcote £5,000 23 3 David Gilbert £45,000 52 51 Mark King £5,000 12 4 Mark Allen £26,000 77 52 Rory McLeod £5,000 63 5 Jimmy Robertson £25,000 73 53 Jianbo Zhao £5,000 51 6 Elliot Slessor £20,000 A 54 Michael Georgiou £5,000 24 7 Ali Carter £18,000 59 55 David Grace £5,000 32 8 Ricky Walden £18,000 NEW 56 Andrew Pagett £5,000 17 9 Zhou Yuelong £12,000 84 57 Ben Hancorn £5,000 35 10 Lu Ning £12,000 NEW 58 Xu Si £5,000 22 11 Tom Ford £11,000 NEW 59 Gerard Greene £4,000 NEW 12 Cao Yupeng £11,000 47 60 Stuart Carrington £4,000 A 13 Bai Langning £11,000 13 61 Barry Hawkins £4,000 1 14 Judd Trump £11,000 76 62 Fergal O'Brien £4,000 72 15 Oliver Lines £11,000 A 63 John Astley £4,000 30 16 Matthew Selt £10,000 NEW 64 Jimmy White £4,000 28 17 Ryan Day £9,000 25 65 Martin Gould £4,000 6 18 Kyren Wilson £9,000 NEW 66 Barry Pinches £4,000 A 19 David Lilley £9,000 68 67 Robbie Williams £4,000 15 20 Stuart Bingham £9,000 A 68 Dylan Emery £4,000 44 21 Noppon Saengkham £8,000 NEW 69 Ian Burns £4,000 80 22 Lukas Kleckers £8,000 61 70 Dominic Dale £4,000 A 23 Ross Muir £8,000 42 71 Mark Joyce £3,000 62 24 Joe O'Connor £8,000 3 72 Ronnie O'Sullivan £3,000 NEW 25 Zhang Jiankang £8,000 NEW 73 Andy Hicks £3,000 81 26 Ashley Hugill £7,000 NEW 74 Chen Zifan £3,000 -

Popular Protest in Contemporary China: a Comprehensive Approach

Popular Protest in Contemporary China: A Comprehensive Approach Popular protest has been frequent in post-1989 China. It has included activism by farmers, workers, and homeowners; environmental activism; nationalist protests; political activism; separatist unrest by Uighurs and Tibetans; and quasi-separatist activism in Hong Kong. These actions have drawn a great deal of scholarly attention, resulting in a rich body of research. However, nearly all focus only on a particular category of citizen collective action. Further, the few studies that examine protest more broadly were written before Xi Jinping assumed the Chinese Party-state’s top posts in 2012, and do not include all of the types of contention listed above. This paper is the first to take a truly comprehensive approach that collectively examines the wide array of protests across China from the 1990s through the present. In so doing, it uncovers patterns that are not found in other studies. Specifically, the paper underscores how protest emergence and success have been impacted by: 1) divisions within the political leadership; 2) laws and official pronouncements; 3) the socioeconomic status and resources of the aggrieved; and 4) the nature of citizen complaints and actions. Based on these findings, the paper concludes with an assessment of their implications for the legitimacy and stability of Chinese Communist Party rule. Teresa Wright Chair and Professor Political Science California State University, Long Beach Prepared for delivery at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Western Political Science Association San Francisco, CA, March 29-31, 2018 *Please do not cite or quote without the author’s permission 1 Popular Protest in Contemporary China: A Comprehensive Approach Teresa Wright Popular protest has been frequent in post-1989 China. -

World Ranking List After 2019 International

WORLD RANKINGS AFTER THE 2019 INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP Start Current Prize Money Ranking Ranking Player Name Rankings 2 1 Judd Trump 1,334,500 1 2 Ronnie O'Sullivan 1,178,500 3 3 Mark Williams 1,002,750 4 4 Neil Robertson 851,000 5 5 John Higgins 802,000 6 6 Mark Selby 781,225 7 7 Mark Allen 705,000 8 8 Kyren Wilson 567,725 10 9 Ding Junhui 418,000 9 10 Barry Hawkins 406,250 11 11 Jack Lisowski 403,350 12 12 David Gilbert 399,500 13 13 Stuart Bingham 394,000 14 14 Shaun Murphy 375,000 16 15 Stephen Maguire 317,500 17 16 Ali Carter 291,500 19 17 Joe Perry 288,500 21 18 Yan Bingtao 287,500 20 19 Gary Wilson 267,100 18 20 Ryan Day 242,750 22 21 Graeme Dott 241,000 24 22 Jimmy Robertson 226,225 23 23 Anthony McGill 221,500 25 24 Xiao Guodong 209,600 15 25 Luca Brecel 209,100 27 26 Tom Ford 197,725 26 27 Lyu Haotian 193,500 28 28 Mark King 184,475 30 29 Ricky Walden 184,100 34 30 Matthew Selt 178,850 35 31 Scott Donaldson 172,000 36 32 Ben Woollaston 162,100 39 33 Robert Milkins 162,100 41 34 Liang Wenbo 162,000 32 35 Martin Gould 161,750 31 36 Zhou Yuelong 158,250 37 37 Thepchaiya Un-Nooh 157,475 33 38 Mark Davis 156,225 38 39 Noppon Saengkham 150,600 29 40 Li Hang 150,000 40 41 Hossein Vafaei 147,500 42 42 Martin O'Donnell 146,100 44 43 Michael Holt 139,750 49 44 Kurt Maflin 139,200 43 45 Matthew Stevens 130,750 47 46 Peter Ebdon 128,750 45 47 Michael White 128,250 54 48 Mark Joyce 127,750 12/08/2019 WORLD RANKINGS AFTER THE 2019 INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP Start Current Prize Money Ranking Ranking Player Name Rankings 48 49 Chris Wakelin -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Effects of the Internet on Collective Democratic Action in China Chen, Xiaojin Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 The Effects of the Internet on Collective Democratic Action in China Xiaojin Chen / 1219305 PhD Thesis Department of Culture, MeDia anD Creative InDustries King’s College London 2016 Abstract Focussing on the effects of the Internet on collective democratic action in China, this research seeks to understand the ways in which the Internet may promote civic participation and the public sphere in China. -

(709) Crackdown: the Future of Human Rights Lawyering

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 41, Issue 5 2018 Article 3 After the July 9 (709) Crackdown: The Future of Human Rights Lawyering Hualing Fu∗ Han Zhuy ∗ y Copyright c 2018 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj ARTICLE AFTER THE JULY 9 (709) CRACKDOWN: THE FUTURE OF HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYERING Hualing Fu & Han Zhu* I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................1135 II. TRIVIALITY ...............................................................1138 III. COOPTATION .............................................................1146 IV. RESILIENCE ...............................................................1156 V. CONCLUSION ............................................................1163 I. INTRODUCTION Eighteen months after the 709 crackdown on human rights lawyers,1 a debate took place within China’s human rights lawyers’ communities. 2 It is a brief, yet passionate and provocative debate focusing on some of the fundamental questions about law’s limits in seeking justice and protecting rights in an authoritarian state and the limited role of lawyers in their endeavour. Having grown for about twenty years since the mid-1990s, human rights lawyers have engaged in social-legal activism in wide policy areas including consumer protection, anti-discrimination, rights in the criminal process, and the * Faculty of law, The University of Hong Kong. This research was supported by a grant from the RGC General Research Fund (HKU17613515). 1. For a critical analysis of the crackdown, see Fu Hualing, The July 9th (709) Crackdown on Human Rights Lawyers: Legal Advocacy in an Authoritarian State, J. OF CONTEMPORARY CHINA (forthcoming, 2018). 2. See, e.g., Chen Jiangang, Zhang Sizhi Lun [Thoughts on Zhang Sizhi] (Nov. 15, 2016), http://www.mychinese.news/2016/11/blog-post_16.html [https://perma.cc/EV4C-88JY]; Yan Wenxin, Zaitan Gean Tuidong Fazhi [Rethink About Promoting Rule of Law Through Individual Cases, WALL OUTSIDE (Dec. -

The Rights Defence Movement, Rights Defence Lawyers and Prospects for Constitutional Democracy in China

The Rights Defence Movement, Rights Defence Lawyers and Prospects for Constitutional Democracy in China Chongyi Feng Abstract Contrary to the view that democratic aspiration has been utterly marginalised in China since the 1990s, the discourse of democracy continues to flourish via the Internet and other means of communication, and a budding “rights defence movement” (weiquan yundong) has emerged as a new focus of the Chinese democracy movement in China. The emergence of this rights defence movement foreshadows a new, more optimistic political scenario in which transition to a stable constitutional democracy through constructive interactions between state and society may occur. This paper explores the social and political context behind the rise of the rights defence movement in China, assesses the role played by rights defence lawyers (weiquan lushi) in shaping the rights defence movement and speculates on the implications of the rights defence movement for China’s transition to constitutional democracy. Democratisation of communist China is a major international as well as domestic concern. With the Chinese democracy movement shattered in 1989 after the Tiananmen Square crackdown, and with the rapid marginalisation of the dissident democratic activist leaders, a pessimistic view developed among China scholars in the late 1990s predicting that due to its political stagnation and demographic and environmental challenges China was likely to collapse and be left in a state of prolonged domestic chaos and massive human exodus (Chang 2001). More recently, a new and equally pessimistic forecast of “resilient authoritarianism” has gained currency, which argues that China’s authoritarian system is not stagnant but constantly adjusting to new environments, and that the combination of a market economy and political institutionalisation has made the current authoritarian political system sustainable for the foreseeable future (Nathan 2003, Pei 2006). -

Many Voices in China's Legal Profession: Plural Meanings Of

china law and society review 4 (2019) 71-101 brill.com/clsr Many Voices in China’s Legal Profession: Plural Meanings of Weiquan Ethan Michelson Indiana University Bloomington [email protected] Abstract Figuring prominently in prevailing portraits of activism and political contention in contemporary China are weiquan [rights defense] lawyers. Outside of China, the word weiquan emerged in the early 2000s and had achieved near-hegemonic status by the late 2000s as a descriptive label for a corps of activist lawyers—who numbered be- tween several dozen and several hundred—committed to the cause and mobilizing in pursuit of human rights protections vis-à-vis China’s authoritarian party-state. This article challenges the dominant nomenclature of Chinese activism, in which weiquan in general and weiquan lawyers in particular loom large. A semantic history of the word weiquan, traced through an analysis of four decades of officially sanctioned rights discourse, reveals its politically legitimate origins in the official lexicon of the party-state. Unique survey data collected in 2009 and 2015 demonstrate that Chinese lawyers generally understood the word in terms of the party-state’s official language of rights, disseminated through its ongoing public legal education campaign. Because the officially-sanctioned meaning of weiquan, namely “to protect citizens’ lawful rights and interests,” is consistent with the essential professional responsibility of lawyers, fully half of a sample of almost 1,000 practicing lawyers from across China self- identified as weiquan lawyers. Such a massive population of self-identified weiquan lawyers—approximately 80,000 in 2009 assuming that the sample is at least reason- ably representative—makes sense only if local meanings of the term profoundly di- verge from its dominant English-language representations. -

China: Lawyers and Activists Detained Or Questioned by Police Since 9 July 2015

China: Lawyers and Activists detained or questioned by police since 9 July 2015 Amnesty International has collated the list based on various sources and attempted to confirm all information. However, verification remains difficult and not all the information may be up to date. Note: In China, "summoned" refers to a particular procedure detailed in Criminal Law article 92 by which an individual regarded as a "criminal suspect" can be interrogated at a designated place but need not be arrested or formally detained. Total number of lawyers and activists targeted: 248 Total number of lawyers, and activists is still missing or in police custody: 28 (Last update: 4.30pm Beijing time, 13 October 2015) Date Status Chinese name English Name Occupation City/ Province Gender As of 22 September No. Placed under residential surveillance, at an unknown Lawyer, Lawyer of Fengrui Law 1 9 July 2015 4am Taken away 王宇 Wang Yu Beijing F location on suspicion of Firm “inciting subversion of state power”. Placed under residential surveillance at an unknown 2 9 July 2015 12am Taken away 包龙军 Bao Longjun Lawyer, Husband of Wang Yu Beijing M location on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power” on 26 August 2015. Tianjin Police handed him over 9 July 2015 12am; to Bao's sister on 10 July; his 3 17 July 2015 9am; 包卓轩 Bao Zhuoxuan Son of Wang Yu and Bao Longjun Ulanhot/Beijing M Not in police custody** passport was confiscated by 6 October 2015 police; summoned by police; taken away by uniformed 1 officials in Mongla, Myanmar 4 10 July 2015 7am Taken away