Final Research Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Linux Mojo the XYZ of Mobile Tlas PDQ!

Mobile Linux Mojo The XYZ of Mobile TLAs PDQ! Bill Weinberg January 29, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Bill Weinberg, LinuxPundit,com Alphabet Soup . Too many TLAs – Non-profits – Commercial Entities – Tool Kits – Standards . ORG Typology – Standards Bodies – Implementation Consortia – Hybrids MIPS and Open Source Copyright © 2008 Bill Weinberg, LinuxPundit,com Page: 2 The Big Four . Ahem, Now Three . OHA - Open Handset Alliance – Founded by Google, together with Sprint, TIM, Motorola, et al. – Performs/support development of Android platform . LiMo Foundation – Orig. Motorola, NEC, NTT, Panasonic, Samsung, Vodaphone – Goal of created shared, open middleware mobile OS . LiPS - Linux Phone Standards Forum – Founded by France Telecom/Orange, ACCESS et al. – Worked to create standards for Linux-based telephony m/w – Merged with LiMo Foundation in June 2008 . Moblin - Mobile Linux – Founded by Intel, (initially) targeting Intel Atom CPUs – Platform / distribution to support MIDs, Nettops, UMPC MIPS and Open Source Copyright © 2008 Bill Weinberg, LinuxPundit,com Page: 3 LiMo and Android . Android is a complete mobile stack LiMo is a platform for enabling that includes applications applications and services Android, as Free Software, should LiMo membership represents appeal to Tier II/III OEMs and Tier I OEMs, ISVs and operators ODMs, who lack resources LiMo aims to leave Android strives to be “room for differentiation” a stylish phone stack LiMo presents Linux-native APIs Android is based on Dalvik, a Java work-alike The LiMo SDK has/will have compliance test suites OHA has a “non Fragmentation” pledge MIPS and Open Source Copyright © 2008 Bill Weinberg, LinuxPundit,com Page: 4 And a whole lot more . -

Hildon 2.2: the Hildon Toolkit for Fremantle

Hildon 2.2: the Hildon toolkit for Fremantle Maemo Summit 2009 – Westergasfabriek Amsterdam Alberto Garcia [email protected] Claudio Saavedra [email protected] Introduction Hildon widgets library ● Set of widgets built on top of GTK+ ● Created for Nokia devices based on the Maemo platform: – Nokia 770 – Nokia N800 – Nokia N810 – Nokia N900 ● Released under the GNU LGPL ● Used also in other projects (e.g Ubuntu Mobile) Maemo 5 - Fremantle ● Maemo release for the Nokia N900 ● Modern, usable and finger-friendly UI ● Completely revamped user interface, very different from all previous versions ● Hildon 2.2.0 released on 24 September 2009 Hildon 2.0: Modest http://www.flickr.com/photos/yerga/ / CC BY-NC 2.0 Hildon 2.0: Modest http://www.flickr.com/photos/yerga/ / CC BY-NC 2.0 Hildon 2.2: Modest Hildon 2.2: Modest Hildon source lines of code ● Hildon 1.0 (16 Apr 2007): 23,026 ● Hildon 2.0 (10 Oct 2007): 23,690 ● Hildon 2.2.0 (24 Sep 2009): 36,291 Hildon 2.2: the Fremantle release ● Applications as window stacked views ● Buttons as central UI part ● Scrollable widgets are touchable-friendly ● Kinetic scrolling (HildonPannableArea) Other goals ● New and old-style applications can coexist ● Maintain backward compatibility – No API breakage – UI style preserved (where possible) MathJinni in Fremantle New UI concepts Window stacks ● Hierarchical organization of windows ● Applications have a main view from which different subviews can be opened ● Views: implemented with HildonStackableWindow ● Stacks: implemented with HildonWindowStack Demo HildonButton: -

We've Got Bugs, P

Billix | Rails | Gumstix | Zenoss | Wiimote | BUG | Quantum GIS LINUX JOURNAL ™ REVIEWED: Neuros OSD and COOL PROJECTS Cradlepoint PHS300 Since 1994: The Original Magazine of the Linux Community AUGUST 2008 | ISSUE 172 WE’VE GOT Billix | Rails Gumstix Zenoss Wiimote BUG Quantum GIS MythTV BUGs AND OTHER COOL PROJECTS TOO E-Ink + Gumstix Perfect Billix Match? Kiss Install CDs Goodbye AUGUST How To: 16 Terabytes in One Case www.linuxjournal.com 2008 $5.99US $5.99CAN 08 ISSUE Learn to Fake a Wiimote Linux 172 + UFO Landing Video Interface HOW-TO 0 09281 03102 4 AUGUST 2008 CONTENTS Issue 172 FEATURES 48 THE BUG: A LINUX-BASED HARDWARE MASHUP With the BUG, you get a GPS, camera, motion detector and accelerometer all in one hand-sized unit, and it’s completely programmable. Mike Diehl 52 BILLIX: A SYSADMIN’S SWISS ARMY KNIFE Build a toolbox in your pocket by installing Billix on that spare USB key. Bill Childers 56 FUN WITH E-INK, X AND GUMSTIX Find out how to make standard X11 apps run on an E-Ink display using a Gumstix embedded device. Jaya Kumar 62 ONE BOX. SIXTEEN TRILLION BYTES. Build your own 16 Terabyte file server with hardware RAID. Eric Pearce ON THE COVER • Neuros OSD, p. 44 • Cradlepoint PHS300, p. 42 • We've got BUGs, p. 48 • E-Ink + Gumstix—Perfect Match?, p. 56 • How To: 16 Terabytes in One Case, p. 62 • Billix—Kiss Install CDs Goodbye, p. 52 • Learn to Fake a UFO Landing Video, p. 80 • Wiimote Linux Interface How-To, p. 32 2 | august 2008 www.linuxjournal.com lj026:lj018.qxd 5/14/2008 4:00 PM Page 1 The Straight Talk People -

Pipenightdreams Osgcal-Doc Mumudvb Mpg123-Alsa Tbb

pipenightdreams osgcal-doc mumudvb mpg123-alsa tbb-examples libgammu4-dbg gcc-4.1-doc snort-rules-default davical cutmp3 libevolution5.0-cil aspell-am python-gobject-doc openoffice.org-l10n-mn libc6-xen xserver-xorg trophy-data t38modem pioneers-console libnb-platform10-java libgtkglext1-ruby libboost-wave1.39-dev drgenius bfbtester libchromexvmcpro1 isdnutils-xtools ubuntuone-client openoffice.org2-math openoffice.org-l10n-lt lsb-cxx-ia32 kdeartwork-emoticons-kde4 wmpuzzle trafshow python-plplot lx-gdb link-monitor-applet libscm-dev liblog-agent-logger-perl libccrtp-doc libclass-throwable-perl kde-i18n-csb jack-jconv hamradio-menus coinor-libvol-doc msx-emulator bitbake nabi language-pack-gnome-zh libpaperg popularity-contest xracer-tools xfont-nexus opendrim-lmp-baseserver libvorbisfile-ruby liblinebreak-doc libgfcui-2.0-0c2a-dbg libblacs-mpi-dev dict-freedict-spa-eng blender-ogrexml aspell-da x11-apps openoffice.org-l10n-lv openoffice.org-l10n-nl pnmtopng libodbcinstq1 libhsqldb-java-doc libmono-addins-gui0.2-cil sg3-utils linux-backports-modules-alsa-2.6.31-19-generic yorick-yeti-gsl python-pymssql plasma-widget-cpuload mcpp gpsim-lcd cl-csv libhtml-clean-perl asterisk-dbg apt-dater-dbg libgnome-mag1-dev language-pack-gnome-yo python-crypto svn-autoreleasedeb sugar-terminal-activity mii-diag maria-doc libplexus-component-api-java-doc libhugs-hgl-bundled libchipcard-libgwenhywfar47-plugins libghc6-random-dev freefem3d ezmlm cakephp-scripts aspell-ar ara-byte not+sparc openoffice.org-l10n-nn linux-backports-modules-karmic-generic-pae -

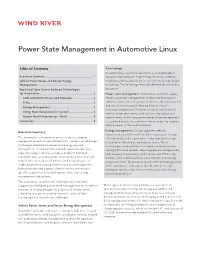

Power State Management in Automotive Linux

Power State Management in Automotive Linux Table of Contents Terminology As automotive, consumer electronics, and embedded Executive Summary ............................................................1 software and hardware engineering intersect, technical Vehicle Power States and Device Energy traditions and vocabulary for in-car systems design begin Management ......................................................................1 to overlap. The following terms are defined for use in this Key Linux/Open Source Software Technologies document. for Automotive ...................................................................2 Power state management: Automakers and their supply CAN and MOST Drivers and Protocols ..........................2 chains use power management to describe the state of D-Bus ..............................................................................3 vehicles and in-vehicle systems relative to their policies for and use of electric power flowing from a vehicle’s Energy Management ......................................................3 alternator and battery. To minimize confusion between Initng: Next-Generation Init System ..............................3 familiar automotive terms and current embedded and System Health Monitoring – Monit ................................4 mobile terms, in this document power state management Conclusion ..........................................................................4 is used to describe the software infrastructure to support vehicle power states and transitions. Energy -

Forging a Community – Not: Experiences on Establishing an Open Source Project

Forging A Community – Not: Experiences On Establishing An Open Source Project Juha Järvensivu1 and Tommi Mikkonen1 1 Institute of Software Systems, Tampere University of Technology Korkeakoulunkatu 1, FI-33720 Tampere, Finland {juha.jarvensivu, tommi.mikkonen}@tut.fi Abstract. Open source has recently become a practical and advocated fashion to develop, integrate, and license software. As a consequence, open source communities that commonly perform the development work are becoming im- portant in the practice of software engineering. A community that is lively can often produce high-quality systems that continuously grow in terms of fea- tures, whereas communities that do not gain interest will inevitably perish. De- spite their newly established central role, creation, organization, and manage- ment of such communities have not yet been widely studied from the viewpoint of software engineering practices. In this paper, we discuss experi- ences gained in the scope of Laika, an open source project established to de- velop an integrated software development environment for developing applica- tions that run in Linux based mobile devices. Keywords: Software engineering, open source community establishment 1 Introduction Open source development has recently become a practical fashion to develop dif- ferent types of software systems. This also affects commercial systems, where open source code can be used in tools, platforms, and general-purpose libraries, for in- stance. Also commercial systems that are largely based on open source components exist, as contrary to the common misbelief these are not contradicting concepts. A good example of such a system is Nokia 770 Internet Tablet, which is based on popular open source components. -

Basics of Mobile Linux Programming

Basics of Mobile Linux Programming Matthieu Weber ([email protected]), 2010 Plan • Linux-based Systems • Scratchbox • Maemo • Meego • Python Linux-based Systems What Linux is Not • An operating system: Linux is only a kernel • A washing powder (in the context of this course) A Short History • 1983: GNU project (“GNU is Not Unix”) • 1987: Minix (as a teaching tool) • 1991: Linux kernel in Minix 1.5 • 1992: Linux becomes GNU’s kernel (Hurd is not ready) Relation to Unix • Unix was developped in 1969 by AT&T at Bell Labs • Many incompatible variants of Unix made by various manufacturers • Standardisation attempt (POSIX) in 1988 • Linux implements POSIX (kernel part) • GNU implements POSIX (application part) Distributions (1) • Linux distributions are made of – a Linux kernel, – GNU and non-GNU applications, – a package management system – a system installation tool • Examples: RedHat EL/Fedora Core, Slackware, Debian, Mandriva, S.u.S.E, Ubuntu MW/2009/TIES425/Basics 1 Distributions (2) • Distributions provide a comprehensive collection of software which are easy to install with the package management tools • Packages are tested to work with each other (compatible versions of libraries, no file-name collision. ) • Packages often have explicit dependencies on each-other ⇒ when installing a software, the required libraries can be installed at the same time • The origin of the packages can be authenticated ⇒ less risk to install malware GNU General Public Licence • Software licence for GNU, used by Linux • Free software licence, enforces the -

Debian and Ubuntu

Debian and Ubuntu Lucas Nussbaum lucas@{debian.org,ubuntu.com} lucas@{debian.org,ubuntu.com} Debian and Ubuntu 1 / 28 Why I am qualified to give this talk Debian Developer and Ubuntu Developer since 2006 Involved in improving collaboration between both projects Developed/Initiated : Multidistrotools, ubuntu usertag on the BTS, improvements to the merge process, Ubuntu box on the PTS, Ubuntu column on DDPO, . Attended Debconf and UDS Friends in both communities lucas@{debian.org,ubuntu.com} Debian and Ubuntu 2 / 28 What’s in this talk ? Ubuntu development process, and how it relates to Debian Discussion of the current state of affairs "OK, what should we do now ?" lucas@{debian.org,ubuntu.com} Debian and Ubuntu 3 / 28 The Ubuntu Development Process lucas@{debian.org,ubuntu.com} Debian and Ubuntu 4 / 28 Linux distributions 101 Take software developed by upstream projects Linux, X.org, GNOME, KDE, . Put it all nicely together Standardization / Integration Quality Assurance Support Get all the fame Ubuntu has one special upstream : Debian lucas@{debian.org,ubuntu.com} Debian and Ubuntu 5 / 28 Ubuntu’s upstreams Not that simple : changes required, sometimes Toolchain changes Bugfixes Integration (Launchpad) Newer releases Often not possible to do work in Debian first lucas@{debian.org,ubuntu.com} Debian and Ubuntu 6 / 28 Ubuntu Packages Workflow lucas@{debian.org,ubuntu.com} Debian and Ubuntu 7 / 28 Ubuntu Packages Workflow Ubuntu Karmic Excluding specific packages language-(support|pack)-*, kde-l10n-*, *ubuntu*, *launchpad* Missing 4% : Newer upstream -

Using Generic Platform Components

Maemo Diablo Reference Manual for maemo 4.1 Using Generic Platform Components December 22, 2008 Contents 1 Using Generic Platform Components 3 1.1 Introduction .............................. 3 1.2 File System - GnomeVFS ....................... 4 1.3 Message Bus System - D-Bus .................... 12 1.3.1 D-Bus Basics .......................... 12 1.3.2 LibOSSO ............................ 24 1.3.3 Using GLib Wrappers for D-Bus .............. 44 1.3.4 Implementing and Using D-Bus Signals .......... 66 1.3.5 Asynchronous GLib/D-Bus ................. 81 1.3.6 D-Bus Server Design Issues ................. 91 1.4 Application Preferences - GConf .................. 98 1.4.1 Using GConf ......................... 98 1.4.2 Using GConf to Read and Write Preferences ....... 100 1.4.3 Asynchronous GConf .................... 107 1.5 Alarm Framework .......................... 114 1.5.1 Alarm Events ......................... 115 1.5.2 Managing Alarm Events ................... 119 1.5.3 Checking for Errors ...................... 120 1.5.4 Localized Strings ....................... 121 1.6 Usage of Back-up Application .................... 123 1.6.1 Custom Back-up Locations ................. 123 1.6.2 After Restore Run Scripts .................. 124 1.7 Using Maemo Address Book API .................. 125 1.7.1 Using Library ......................... 125 1.7.2 Accessing Evolution Data Server (EDS) .......... 127 1.7.3 Creating User Interface ................... 132 1.7.4 Using Autoconf ........................ 136 1.8 Clipboard Usage ........................... 137 1.8.1 GtkClipboard API Changes ................. 137 1.8.2 GtkTextBuffer API Changes ................. 137 1.9 Global Search Usage ......................... 138 1.9.1 Global Search Plug-ins .................... 139 1.10 Writing "Send Via" Functionality .................. 141 1.11 Using HAL ............................... 142 1.11.1 Background .......................... 143 1.11.2 C API ............................. -

GNOME Annual Report 2008

1 Table of Contents Foreword Letter from the Executive Director 4 A year in review GNOME in 2008 8 GNOME Mobile 16 Events and Community initiatives Interview with Willie Walker 20 GNOME around the world 24 GNOME Foundation Foundation Finances 30 List of all 2008 donors 33 2 Letter from Stormy Peters Stormy Peters is the GNOME Foundation Executive Director and has great experience in the industry and with the open source culture. Hello GNOME Lovers! seek them out and to invite them to come play. (Actually, I felt welcome from day -1, GNOME's goal is to bring free and open as I met a bunch of guys on the plane who source computing to everyone regardless of turned out to also be going to GUADEC. I ability. I consider myself extremely lucky to spent my first day in Copenhagen walking have joined the project as executive director around with some guys from Red Hat and of the GNOME Foundation. It's a pleasure Eazel trying to stay awake through jetlag. I and a privilege to work with thousands of pe- remember Havoc Pennington saying we just ople dedicated to making free had to stay awake until dinner software available for everyone The spirit and time.) on desktops and mobile plat- dedication of the forms. I don't think it's an GNOME community to One of the most common exaggeration to say that their goals of creating questions I get asked is GNOME technology is chan- a free and open source why did you take this job? ging the world for many from software .. -

Ubuntu Mobile & Embedded

Ubuntu Mobile & Embedded David Mandala 16 April 2008 Copyright © Canonical, LTD. 2008 Topics What is a MID What is Ubuntu Mobile & Embedded Intel Community Resources Copyright © Canonical, LTD. 2008 What is a MID? Consumer centric device Simple and Rich Experience Gen Y Intuitive UI Digital Parents Integrated applications Task oriented device ªInvisibleº Linux OS Communication Entertainment Information Productivity (secondary use case) Copyright © Canonical, LTD. 2008 Ubuntu Mobile & Embedded Completely new product based on Ubuntu core technology Incorporates some open source components from maemo.org Adds new mobile applications developed by Intel Adapts existing open source applications for mobile devices Challenges: Applications can©t fit on small screens Applications are designed for keyboard and mouse, not fingers and touch screen Different expectations for a consumer device Copyright © Canonical, LTD. 2008 Ubuntu Mobile & Embedded How is it different from Ubuntu desktop? User experience for MID end users, not Linux experts GNOME Mobile (Hildon) instead of GNOME desktop Apps are optimized to fit 4.5º-7º touch LCDs Kernel, drivers and libraries optimized for LPIA WiFi, WiMax, 3G and Bluetooth built-in Fits in 500MB flash/SSD, for 2GB+ devices Who is it for? ODMs and OEMs making MIDs ISVs developing MID apps Copyright © Canonical, LTD. 2008 Ubuntu Mobile Architecture eBooks PIM Camera Video Conferencing Email Browser Instant Messaging Flash D-Bus gstreamer Hildon Media player / Helix HAL GTK Document / PDF Accelerated Codecs WiFi, WiMAX, HSDPA, WPA, DHCP, DNS, mDNS, Bluetooth X11, Cairo, Pango, OpenGL Network I/O Drivers Linux Kernel 2.6.24 & Libraries Drivers Copyright © Canonical, LTD. 2008 Intel Created http://www.moblin.org/ as a place for specific Intel software for MIDs. -

Quarterly Report

Quarterly Report GNOME Foundation Providing a Free Desktop for the World October, November, December 2009 Hi GNOME Foundation members and releases, you'll see the amazing fans, amount of ork the ac"essibility team is doing in preparation for GNOME /$, Q4 is normally a quiet quarter - but and much, mu"h more$ not for GNOME! We ended the year ith a lot of really productive activity$ 4ead on to hear hat GNOME teams We had a record four ha"%fests and ha#e a""omplished in Q4! t o summits, the Boston Summit and GNOME (sia. Lots of progress as 1f you'd li%e to re"ei#e this report #ia made, plans ere set for +,-0 and email, please let me %no at e.re all looking for ard to GNOME stormy5gnome.org. 6lease use the /$0! subject, 7'ubs"ribe to GNOME Quarterly 4eport #ia email"$ As you "an see from the followin* team updates, the hole "ommunity Best ishes and hap!y ha"%ing! has been busy and not just at events$ En0oy your GNOME des%top! 1n this issue you.ll find the first Stormy Peters quarterly update from the GNOME Executive Director, Board of 2irectors, you'll learn hat GNOME Foundation %eeps the release team busy bet een Board of Directors Brian 8ameron First of all, the GNOME Foundation that events and ha"%fests are essential October to dis"uss finan"es and to board of dire"tors ould li%e to ex!ress for GNOME "ommunity planning, and ensure that the advisory board felt the a huge thank you to all the #olunteers has orked hard in the Q4 timeframe to raising of fees as a*reeable.