Using and Then There Were None to Teach Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Then There Were None Test Match Each Set of Characters to Their Descriptions. A. Mr. Rogers B. Vera C. Macarthur

And Then There Were None Test Match each set of characters to their descriptions. a. Mr. Rogers b. Vera c. Macarthur d. Emily Brent e. Lombard 1. Killed someone for having an affair with his wife. 2. Killed an employer by withholding medicine. 3. Abandoned a group of men without any food. 4. Allowed a weak young boy to drown. 5. Led someone to suicide through moral judgment. a. Wargrave b. Mrs. Rogers c. Blore d. Marston e. Armstrong 6. Killed someone by being too reckless. 7. Famous for making harsh judgments. 8. Committed perjury, which lead to the death of an innocent man. 9. Killed someone by operating on them while drunk. 10. Worked with another person to kill someone. a. Beatrice b. Hugo c. Cyril d. Narracott e. Morris 11. Conducted the purchase of Indian Island for an unnamed third party. 12. Drowned herself after becoming pregnant. 13. Knew a murder had been committed in order to win his love. 14. Drowned when allowed to swim too far out to sea. 15. Captain of the boat that took the guests to Indian Island Choose the correct answer to each question. 16. What hangs above the mantelpiece in each bedroom in the house on Indian Island? a. a seascape c. a map of the island b. a framed nursery rhyme d. a picture of Mr. U.N. Owen 17. Of what crime does the “voice” accuse each person? a. adultery c. murder b. extortion d. arson 18. Who faints when they hear the accusations? a. Vera Claythorne c. Mrs. -

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie Character descriptions - anything that is in quotations is taken directly from Ms. Christie’s original novel and are her words. We will be using her descriptions and analysis of the characters to develop ours for this production. Ethel Rogers, Blore and Lombard are the comic relief of this play and I will look for them to be played as such. I expect quick timing for this show even though it is a drama. I will be looking for actors who bring a fresh, new approach to a very old play. Thomas Rogers - 30s - 50s (68 speeches) He is a competent, middle aged manservant, not a butler but a house parlor man. He is quick and deft and just a trifle specious and shifty. “A tall lank man, grey-haired and very respectable.” He and his wife are hired to handle housekeeping and cooking for the guests on soldier island. To the guests he appears dignified and dutiful but when their backs are turned he is shady and disrespectful. Proper English Accent Ethel Rogers - 30s - 50s (25 speeches) Thomas wife, she is a worried, frightened looking woman. “She is pale and ghostlike with a flat, monotonous voice. Very respectable looking with her hair dragged back from her face. She had queer, light eyes that shift the whole time from place to place. Frightened of her own shadow she looked like a woman who walked in mortal fear.” She is also a bit of a gossip. Cockney or Irish accent Vera Claythorne - 20s (256 speeches) She is a school teacher who comes to the island to act as a secretary for the mysterious owners. -

Does Crime Literature Contribute to the Stigmatisation of Those with Mental Health Problems? 95

Antoniou Crime literature and stigmatisation of mental illness 2. It is important to remember that not all Sikhs wear Nothing defeats cross-cultural ignorance, anxieties the kirpan and the issue will arise in only a small and prejudices better than simple, straightforward and number of Sikh patients. accurate information. Sometimes an excessive and inap- special 3. If a patient is wearing the kirpan, the staff should propriate concern about cultural sensitivity masks a articles not automatically assume that it is dangerous. patronisingly dismissive attitude to the cultural needs of However, it may be necessary to examine the minority groups. Alternatively, genuine cultural sensitivity kirpan to ensure safety. and concern about transgressing cultural boundaries may 4. If there are concerns about safety, these should be lead to important issues being ignored. For staff looking discussed openly but sensitively with the patient after patients from ethnic minority groups, this can be a and carers, explaining that the concerns are about delicate balancing act. It is hoped that at least in the area safety and in no way challenging or judgmental of of Sikh patients wearing a kirpan and safety concerns, the the religious traditions of Sikhs. above recommendations will help staff to look after 5. Patients and carers should be allowed to express patients in a clinically and culturally appropriate manner. their views including ventilation of any distress, since for devout Sikhs, the five Ks are the paramount and highly emotive articles of faith. Acknowledgement Brusque, confrontational or insensitive handling of the discussion is only likely to appear insulting, and I am grateful to Mr Indarjit Singh OBE for checking the may polarise and entrench opinions. -

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie

Novel Guide • Teacher Edition • Grades 7 & 8 And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie Published and Distributed by Amplify. Copyright © 2019 by Amplify Education, Inc. 55 Washington Street, Suite 800, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.amplify.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form, or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of Amplify Education, Inc., except for reprinting and/or classroom uses in conjunction with current licenses for the corresponding Amplify products. Table of Contents Teacher Edition Welcome to Amplify ELA’s Novel Guides 1 Part 1: Introduction 2–3 Part 2: Text Excerpt and Close Reading Activities 4–7 RL.7.6, RL.8.6 Step 1: Close Reading Activity 6 RL.7.1, RL.7.4, RL,7.6, RL.8.1, RL.8.4, RL.8.6 Step 2: Connected Excerpts to Continue Close Reading 7 RL.7.6, RL.8.6 Step 3: Writing Prompt 7 W.7.1, W.8.1 Part 3: Additional Guiding Questions and Projects Step 4: Guiding Questions to Read the Whole Book 8–9 SL.7.1, SL.8.1 Step 5: Extended Discussion Questions 9–10 RL.7.2, RL.7.3, RL.7.4, RL.7.5, SL.7.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.3, RL.8.4, RL.8.5, SL.8.1 Step 6: Writer’s Craft 10 RL.7.4, RL.7.6, RL.8.4, RL.8.6 Part 4: Summative Projects Step 7: Writing Prompt 11 W.7.1, W.8.1 Step 8: Final Project 11–12 RL.7.7, W.7.4, W.7.8, SL.7.5, RL.8.7, W.8.4, W.8.8, SL.8.5 Step 9: Challenge 13 RL.7.1, W.7.7, W.7.9, RL.8.1, W.8.7, W.8.9 Step 10: Extra 13–14 RL.7.4, RL.7.5, W.7.3.A, W.7.3.E, RL.8.4, RL.8.5, W.8.3.A, W.8.3.E Step 11: Extended Reading 15 Note: The student worksheets can be found on pages 17–31. -

Hercule Poirot Mysteries in Chronological Order

Hercule Poirot/Miss Jane Marple Christie, Agatha Dame Agatha Christie (1890-1976), the “queen” of British mystery writers, published more than ninety stories between 1920 and 1976. Her best-loved stories revolve around two brilliant and quite dissimilar detectives, the Belgian émigré Hercule Poirot and the English spinster Miss Jane Marple. Other stories feature the “flapper” couple Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, the mysterious Harley Quin, the private detective Parker Pyne, or Police Superintendent Battle as investigators. Dame Agatha’s works have been adapted numerous times for the stage, movies, radio, and television. Most of the Christie mysteries are available from the New Bern-Craven County Public library in book form or audio tape. Hercule Poirot The Mysterious Affair at Styles [1920] Murder on the Links [1923] Poirot Investigates [1924] Short story collection containing: The Adventure of "The Western Star", TheTragedy at Marsdon Manor, The Adventure of the Cheap Flat , The Mystery of Hunter's Lodge, The Million Dollar Bond Robbery, The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb, The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan, The Kidnapped Prime Minister, The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim, The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman, The Case of the Missing Will, The Veiled Lady, The Lost Mine, and The Chocolate Box. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd [1926] The Under Dog and Other Stories [1926] Short story collection containing: The Underdog, The Plymouth Express, The Affair at the Victory Ball, The Market Basing Mystery, The Lemesurier Inheritance, The Cornish Mystery, The King of Clubs, The Submarine Plans, and The Adventure of the Clapham Cook. The Big Four [1927] The Mystery of the Blue Train [1928] Peril at End House [1928] Lord Edgware Dies [1933] Murder on the Orient Express [1934] Three Act Tragedy [1935] Death in the Clouds [1935] The A.B.C. -

If You Want to Read the Books in Publication

If you want to read the books in publication order before you discuss them this is the list for you. For the books the year indicates the first publication, whether in the US or UK, and where possible we have given the alternative US/UK titles. The collections listed are those that feature the first book appearance of one or more stories: 1920 The Mysterious Affair at Styles 1922 The Secret Adversary 1923 Murder on the Links 1924 The Man in the Brown Suit 1924 Poirot Investigates – containing: The Adventure of the ‘Western Star’ The Tragedy at Marsdon Manor The Adventure of the Cheap Flat The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge The Million Dollar Bond Robbery The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan The Kidnapped Prime Minister The Disappearance of Mr Davenheim The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman The Case of the Missing Will 1925 The Secret of Chimneys 1926 The Murder of Roger Ackroyd 1927 The Big Four 1928 The Mystery of the Blue Train 1929 The Seven Dials Mystery 1929 Partners in Crime – containing: A Fairy in the Flat A Pot of Tea The Affair of the Pink Pearl The Adventure of the Sinister Stranger Finessing the King/The Gentleman Dressed in Newspaper The Case of the Missing Lady Blindman’s Buff The Man in the Mist The Crackler The Sunningdale Mystery The House of Lurking Death The Unbreakable Alibi The Clergyman’s Daughter/The Red House The Ambassador’s Boots The Man Who Was No.16 1930 The Mysterious Mr Quin – containing: The Coming of Mr Quin www.AgathaChristie.com The Shadow on the Glass At the ‘Bells -

Techniques of Detective Fiction in the Novelistic Art of Agatha Christie

,,. TECHNIQUES OF DETECTIVE FICTION IN THE NOVELISTIC ART OF AGATHA CHRISTIE A Monograph Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Morehead State University In Partial .FUlfillment of the Requirements for the ~gree Master of Arts b;y Claudia Collins Burns Januar,r, 1975 ...... '. ~- ... '. Accepted by the faculty of the School of H,.;#t.,._j-f;l ..:.3 • Morehead State U¢versi~ in partial· fulfillment of tl!e requirements for the Master of Arts degree. ,·. •: - ',· .· ~.· '1' ' '· .~ ' . ,·_ " 1 J • ~ ,,., ' " . Directorno( Monograph j. ,- .. I . ' U.-g ·'-%· '- .. : . ,. •.·,' . ,• ·- ; -..: ' ~ ' .. ''· ,,, ··. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • l General Statement on the Nature of the }lonoeraph • l . ~ . 3 Previous Work • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 4 Purposes And Specific Elements to be Proven • • • 7 l. AGATHA CHRISTIE AND THE RULES OF DETECTIVE FICTION • 8 The Master Detective •• • • • • • • • • • . • • 8 Clues Before the RE;<itler. ........... • .. 30 Motives for the Crime • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 52 2. ELEMENTS OF SOCIOLOGICAL COMMENTARY IN THE FICTION OF AGATHA CHRISTIE . .. 6a Class Consciousness ................. 62 Statements About Writers and Writings • • • • • • 76 Role of Women Characters • • • • • • • • • • • • • 90 ;". 3. •· . 106 BIBLIOGRAPHY . ~ . 108 APPENDIX . ... ~·..... lll ii INTRODUCTION NATURE OF THE MONOGRAPH, PROCEDURE, PREVIOUS WORK, PURPOSES AND SPECIFIC ELEMENTS TO BE.PROVEN . '. I. GENERAL STATEMENT ON THE NATURE OF THE MONOGRAPH When -

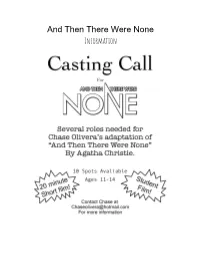

And Then There Were None Information

And Then There Were None Information Hello! This is a 20-minute student film that is in need of actors. There are currently 10 spots available for kids 11-14. The movie is an adaptation of Agatha Christie’s “And Then There Were None,” but with kids instead of adults. Just to let you know, there are some “deaths” that will be in the movie. Nothing will be shown, but I just wanted to let you guys know. About me: My name is Chase Olivera, I am in the 7th grade, and I really like making short films. This is my first adaptation and I would love to make it the best it can be. Synopsis: Ten strangers are lured to an isolated school by a mysterious "U. N. Owen." At dinner a recorded message accuses each of them in turn of having a guilty secret, and by the end of the night one of the guests is dead. Trapped in the school, and haunted by a nursery rhyme counting down one by one . as one by one . they begin to die. Which among them is the killer and will any of them survive? Characters in order of screen-time: Name: Gender: Lawrence Wargrave Male (Villain) Vera Claythorne Female Philip Lombard Male William Blore Male George Armstrong Male Emily Brent Female Thomas Rogers Male John MacArthur Male Ethel Rogers Female Anthony Marston Male If we end up with different numbers of people, we can change the gender of the characters to fit the actor. Adaptation: ● Characters will be kids instead of Adults ● Setting will be in a school instead of a mansion ● It will be more kid-friendly After production: After I finish editing the film, I will post it on Youtube. -

Miss Marple Mysteries 02 the Thirteen Problems

p q The Thirteen Problems To Leonard and Katherine Woolley 5 Contents About Agatha Christie The Agatha Christie Collection E-Book Extras 1 The Tuesday Night Club 9 2 The Idol House of Astarte 29 3 Ingots of Gold 53 4 The Bloodstained Pavement 73 5 Motive v Opportunity 89 6 The Thumb Mark of St Peter 109 7 The Blue Geranium 131 8 The Companion 157 9 The Four Suspects 185 10 A Christmas Tragedy 209 11 The Herb of Death 237 12 The Affair at the Bungalow 261 13 Death by Drowning 285 Copyright www.agathachristie.com About the Publisher 7 Chapter 7 The Blue Geranium ‘When I was down here last year –’ said Sir Henry Clithering, and stopped. His hostess, Mrs Bantry, looked at him curiously. The Ex-Commissioner of Scotland Yard was staying with old friends of his, Colonel and Mrs Bantry, who lived near St Mary Mead. Mrs Bantry, pen in hand, had just asked his advice as to who should be invited to make a sixth guest at dinner that evening. ‘Yes?’ said Mrs Bantry encouragingly. ‘When you were here last year?’ ‘Tell me,’ said Sir Henry, ‘do you know a Miss Marple?’ Mrs Bantry was surprised. It was the last thing she had expected. ‘Know Miss Marple? Who doesn’t! The typical old maid of fiction. Quite a dear, but hopelessly behind 131 p q the times. Do you mean you would like me to ask her to dinner?’ ‘You are surprised?’ ‘A little, I must confess. I should hardly have thought you – but perhaps there’s an explanation?’ ‘The explanation is simple enough. -

HARPERCOLLINS WELCOMES AGATHA CHRISTIE!!! **Completely Repackaged and Available Starting in Winter 2011!!**

HARPERCOLLINS WELCOMES AGATHA CHRISTIE!!! **Completely repackaged and available starting in Winter 2011!!** For the first time in history, the entire Agatha Christie collection will be published by a single publisher worldwide. Completely repackaged with brand new covers, all titles will be available in trade paperback with Christie’s signature font on the front cover. Each of her beloved series (Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, and Tommy & Tuppence) will be noted with a logo for each on the top- left front, spine, and back of the book. Title listings on the backs of the books, as well as comprehensive ad cards and back-ads, will help AVAILABLE NOW: readers know where to start And Then There Were None with Christie—and what to ISBN: 9780062073471 read next. Murder on the Orient Express Now is the perfect time to ISBN: 9780062073495 stock up on the world’s bestselling mystery writer. Release: 12/28/2010 Don’t miss a single title by On Sale: 1/18/2011 Agatha Christie—the Queen Price: $12.99 ($14.99 CAN) of Mystery! Trade PB / 5 5/16 x 8” Also available as e-books Explore more at www.AgathaChristie.com. Available February 2011: The A.B.C. Murders: 9780062073587 Death on the Nile: 9780062073556 Five Little Pigs: 9780062073570 The Murder of Roger Ackroyd: 9780062073563 Crooked House: 9780062073532 Endless Night: 9780062073518 Ordeal by Innocence: 9780062073525 Towards Zero: 9780062073549 Release: 1/12/2011 On Sale: 2/1/2011 Price: $12.99 ($14.99 CAN) Trade PB / 5 5/16 x 8” Also available as e-books Available April 2011: And Then There Were None -

Agatha Christie

Po Leung Kuk Lo Kit Sing (1983) College School Library Recommended_booklist -- Agatha Christie Accession No. Class No. Author Code Title Author A020125 F CHR Murder in the Mews CHRISTIE, Agatha A020137 F CHR Elephants can remember CHRISTIE, Agatha A020149 F CHR N or M ? CHRISTIE, Agatha A020150 F CHR Sparkling cyanide CHRISTIE, Agatha A020162 F CHR The mysterious Mr. Quin CHRISTIE, Agatha A020174 F CHR Passenger to Frankfurt CHRISTIE, Agatha A020186 F CHR After the funeral CHRISTIE, Agatha A020198 F CHR The man in the brown suit CHRISTIE, Agatha A020204 F CHR The thirteen problems CHRISTIE, Agatha A020216 F CHR Problem at pollensa bay and other stories CHRISTIE, Agatha A020228 F CHR Partners in crime CHRISTIE, Agatha A02023A F CHR The hound of death CHRISTIE, Agatha A020241 F CHR The mystery of the blue train CHRISTIE, Agatha A020253 F CHR Taken at the flood CHRISTIE, Agatha A020265 F CHR Murder is easy CGRISTIE, Agatha A04222 F CHR Parker Pyne investigates CHRISTIE, Agatha A04223 F CHR The Sittaford mystery CHRISTIE, Agatha A04224 F CHR They came to Baghdad CHRISTIE, Agatha A05074 F CHR Nemesis CHRISTIE, Agatha A05075 F CHR Death on the Nile CHRISTIE, Agatha A05076 F CHR Murder on the Orient Express CHRISTIE, Agatha A05760 F CHR Stories of detection and mystery CHRISTIE, Agatha E01547A F CHR Death comes as the end CHRISTIE, Agatha E037774 F CHR Destination unknown CHRISTIE, Agatha E037786 F CHR The body in the library CHRISTIE, Agatha Agatha Christie's Miss Marple : The life and E037798 F CHR CHRISTIE, Agatha time of Miss Jane Marple -

And Then There Were None Based on the Novel by Agatha Christie

Teacher’s Pet Publications a unique educational resource company since 1989 Dear Prospective Customer: The pages which follow are a few sample pages taken from the LitPlan TeacherPack™ title you have chosen to view. They include: • Table of Contents • Introduction to the LitPlan Teacher Pack™ • fi rst page of the Study Questions • fi rst page of the Study Question Answer Key • fi rst page of the Multiple Choice Quiz Section • fi rst Vocabulary Worksheet • fi rst few pages of the Daily Lessons • a Writing Assignment • fi rst page of the Extra Discussion Questions • fi rst page of the Unit Test Section If you wish to see a sample of an entire LitPlan Teacher Pack,™ go to the link on our home page to view the entire Raisin in the Sun LitPlan Teacher Pack.™ Since all of the Teacher Packs™ are in the same format, this will give you a good idea of what to expect in the full document. If you have any questions or comments, please do not hesitate to contact us; we pride ourselves on our excellent customer service, and we love to hear from teachers. Thank you for taking the time to visit our web site and look at our products! Sincerely yours, Jason Scott, CEO Teacher’s Pet Publications Toll-Free: 800-932-4593 Fax: 888-718-9333 TEACHER’S PET PUBLICATIONS LITPLAN TEACHER PACK™ for And Then There Were None based on the novel by Agatha Christie Written by Susan R. Woodward © 2008 Teacher’s Pet Publications All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-60249-031-4 Item No.