Writing Competition Samples and Tips

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bluebook Citation in Scholarly Legal Writing

BLUEBOOK CITATION IN SCHOLARLY LEGAL WRITING © 2016 The Writing Center at GULC. All Rights Reserved. The writing assignments you receive in 1L Legal Research and Writing or Legal Practice are primarily practice-based documents such as memoranda and briefs, so your experience using the Bluebook as a first year student has likely been limited to the practitioner style of legal writing. When writing scholarly papers and for your law journal, however, you will need to use the Bluebook’s typeface conventions for law review articles. Although answers to all your citation questions can be found in the Bluebook itself, there are some key, but subtle differences between practitioner writing and scholarly writing you should be careful not to overlook. Your first encounter with law review-style citations will probably be the journal Write-On competition at the end of your first year. This guide may help you in the transition from providing Bluebook citations in court documents to doing the same for law review articles, with a focus on the sources that you are likely to encounter in the Write-On competition. 1. Typeface (Rule 2) Most law reviews use the same typeface style, which includes Ordinary Times New Roman, Italics, and SMALL CAPITALS. In court documents, use Ordinary Roman, Italics, and Underlining. Scholarly Writing In scholarly writing footnotes, use Ordinary Roman type for case names in full citations, including in citation sentences contained in footnotes. This typeface is also used in the main text of a document. Use Italics for the short form of case citations. Use Italics for article titles, introductory signals, procedural phrases in case names, and explanatory signals in citations. -

Bluebook & the California Style Manual

4/21/2021 Purposes of Citation 1. To furnish the reader with legal support for an assertion or argument: a) provide information about the weight and persuasiveness of the BLUEBOOK & source; THE CALIFORNIA b) convey the type and degree of support; STYLE MANUAL c) to demonstrate that a position is well supported and researched. 2. To inform the reader where to find the cited authority Do You Know the Difference? if the reader wants to look it up. LSS - Day of Education Adrienne Brungess April 24, 2021 Professor of Lawyering Skills McGeorge School of Law 1 2 Bluebook Parts of the Bluebook 1. Introduction: Overview of the BB 2. Bluepages: Provides guidance for the everyday citation needs of first-year law students, summer associates, law clerks, practicing lawyers, and other legal professionals. Includes Bluepages Tables. Start in the Bluepages. Bluepages run from pp. 3-51. 3. Rules 1-21: Each rule in the Bluepages is a condensed, practitioner-focused version of a rule from the white pages (pp. 53-214). Rules in the Bluepages may be incomplete and may refer you to a rule(s) from the white pages for “more information” or “further guidance.” 4. Tables (1-17): Includes tables T1 – T16. The two tables that you will consult most often are T1 and T6. Tables are not rules themselves; rather, you consult them when a relevant citation rule directs you to do so. 5. Index 6. Back Cover: Quick Reference 3 4 1 4/21/2021 Getting Familiar with the Bluebook Basic Citation Forms 3 ways to In the full citation format that is required when you cite to Common rules include: a given authority for the first time in your document (e.g., present a Lambert v. -

Vol. 123 Style Sheet

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 123 STYLE SHEET The Yale Law Journal follows The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (19th ed. 2010) for citation form and the Chicago Manual of Style (16th ed. 2010) for stylistic matters not addressed by The Bluebook. For the rare situations in which neither of these works covers a particular stylistic matter, we refer to the Government Printing Office (GPO) Style Manual (30th ed. 2008). The Journal’s official reference dictionary is Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. The text of the dictionary is available at www.m-w.com. This Style Sheet codifies Journal-specific guidelines that take precedence over these sources. Rules 1-21 clarify and supplement the citation rules set out in The Bluebook. Rule 22 focuses on recurring matters of style. Rule 1 SR 1.1 String Citations in Textual Sentences 1.1.1 (a)—When parts of a string citation are grammatically integrated into a textual sentence in a footnote (as opposed to being citation clauses or citation sentences grammatically separate from the textual sentence): ● Use semicolons to separate the citations from one another; ● Use an “and” to separate the penultimate and last citations, even where there are only two citations; ● Use textual explanations instead of parenthetical explanations; and ● Do not italicize the signals or the “and.” For example: For further discussion of this issue, see, for example, State v. Gounagias, 153 P. 9, 15 (Wash. 1915), which describes provocation; State v. Stonehouse, 555 P. 772, 779 (Wash. 1907), which lists excuses; and WENDY BROWN & JOHN BLACK, STATES OF INJURY: POWER AND FREEDOM 34 (1995), which examines harm. -

Oh No! a New Bluebook!

Michigan Law Review Volume 90 Issue 6 1992 Oh No! A New Bluebook! James D. Gordon III Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation James D. Gordon III, Oh No! A New Bluebook!, 90 MICH. L. REV. 1698 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol90/iss6/39 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OH NO! A NEW BLUEBOOK! James D. Gordon Ill* THE BLUEBOOK: A UNIFORM SYSTEM OF CITATION. 15th ed. By the Columbia Law Review, the Harvard Law Review, the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, and The Yale Law Journal Cambridge: Harvard Law Review Association. 1991. Pp. xvii, 343. Paper, $8.45. The fifteenth edition of A Uniform System of Citation is out, caus ing lawyers and law students everywhere to hyperventilate with excite ment. Calm down. The new edition is not likely to overload the pleasure sensors in the brain. The title, A Uniform System ofCitation, has always been somewhat odd. The system is hardly uniform, and the book governs style as well as citations. 1 Moreover, nobody calls it by its title; everybody calls it The Bluebook. In fact, the book's almost nameless2 editors have amended the title to reflect this fact: it is now titled The Bluebook.· A Uniform System of Citation. -

Author Citations and the Indexer

Centrepiece to The Indexer, September 2013 C1 Author citations and the indexer Sylvia Coates C4 Tips for newcomers: Wellington 2013 Compiled by Jane Douglas C7 Reflections on the Wilson judging for 2012 Margie Towery Author citations and the indexer Sylvia Coates Sylvia Coates explores the potentially fraught matter of how to handle author citations in the index, looking first at the extensive guidelines followed by US publishers, and then briefly considering British practice where it is rare for an indexer to be given any such guidelines. In both situations the vital thing is to be clear from the very beginning exactly what your client’s expectations are. As an indexing instructor for over 12 years, I have observed discussion of this individual in relationship to their actions that most students assume that indexing names is an easy or to an event and not as a reference as is the case with a task. Unfortunately, as experienced indexers come to under- citation. stand, this is not the case and there are a myriad of issues Editors rightly expect the subject of any text discussion to to navigate when indexing names. An examination of all be included in the index. More problematic are the names of these issues is beyond the scope of this article, and my ‘mentioned in passing.’ Some clients expect to see every discussion will be limited to the indexing of name and author single name included in the text, regardless of whether the citations for US and British publishers. name is a passing mention or not. Other clients thankfully I will define what is and is not an author citation, and allow the indexer to use their own judgement in following briefly review the two major citation systems and style the customary indexing convention on what constitutes a guides pertinent to author citations. -

Rethinking the Boundaries of the Sixth Amendment Right to Choice of Counsel

RETHINKING THE BOUNDARIES OF THE SIXTH AMENDMENT RIGHT TO CHOICE OF COUNSEL I. INTRODUCTION Criminal defense is personal business. For this reason, the Consti- tution’s ample procedural protections for criminal defendants are writ- ten not just to provide a fair trial, but also to put the defendant in con- trol of his own defense. Courts and commentators alike have rec- ognized that the constitutional vision of liberty requires not only protection for the accused, but also the right of the accused to speak and act for himself.1 The Sixth Amendment also reflects the common understanding that the assistance of counsel can be crucial — even necessary — to effective defense,2 but its language and structure nev- ertheless make clear that the rights and their exercise belong to the de- fendant himself, not his lawyer.3 The right to the assistance of counsel has many facets, but its most ancient and fundamental element is the defendant’s right to counsel of his own choosing. Indeed, the Supreme Court has identified choice of counsel as “the root meaning of the constitutional guarantee.”4 Yet ac- tual choice-of-counsel doctrine gives the state broad authority to inter- fere with the exercise of this right. For example, a defendant may not choose an advocate whose representation creates a potential conflict of interest for the defendant, even if the defendant knowingly and intelli- gently waives any objection to the potential conflict,5 and a defendant has no right to be represented by an advocate who is not a current member of a state bar association.6 The remedy for a choice-of- ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1 See, e.g., Faretta v. -

1 the YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 128 STYLE SHEET the Yale Law Journal Follows the Bluebook: a Uniform System of Citation (20Th

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 128 STYLE SHEET The Yale Law Journal follows The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (20th ed. 2015) for citation form and the Chicago Manual of Style (17th ed. 2017) for stylistic matters not addressed by The Bluebook. For the rare situations in which neither of these works covers a particular stylistic matter, we refer to the Government Printing Office (GPO) Style Manual (31st ed. 2016). The Journal’s official reference dictionary is Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. This Style Sheet codifies Journal-specific guidelines that take precedence over these sources. Rules 1-21 correspond to and supplement Rules 1-21 in the Bluebook. Rule 22 focuses on recurring matters of style that are not addressed in the Bluebook. Throughout, several rules have red titles; this indicates a correction to an error in the Bluebook, and these will be removed as the Bluebook is updated. Rule 1: Structure and Use of Citations.......................................................................................................... 3 S.R. 1.1(b): String Citations in Textual Sentences in Footnotes ............................................................... 3 S.R. 1.1: Two Claims in One Sentence ..................................................................................................... 3 S.R. 1.4: Order of Authorities ................................................................................................................... 4 S.R. 1.5(a)(i): Parenthetical Information.................................................................................................. -

Review of “The Law of Judicial Precedent.”

BOOK REVIEW CRAFTING PRECEDENT THE LAW OF JUDICIAL PRECEDENT. By Bryan A. Garner et al. St. Paul, Minn.: Thomson Reuters. 2016. Pp. xxvi, 910. $49.95. Reviewed by Paul J. Watford, Richard C. Chen, and Marco Basile How does the law of judicial precedent work in practice? That is the question at the heart of The Law of Judicial Precedent, the first treatise on the subject in more than 100 years. The treatise sets aside more theoretical and familiar questions about whether and why earlier decisions (especially wrong ones) should bind courts in new cases.1 In- stead, it offers an exhaustive how-to guide for practicing lawyers and judges: how to identify relevant precedents, how to weigh them, and how to interpret them. In short, how to apply precedents to new cases. The treatise’s thirteen authors include representatives from several of the federal circuit courts, justices from two state supreme courts, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s newest member, Justice Neil Gorsuch.2 Their coauthor and the project’s fountainhead, Bryan Garner, is the editor of Black’s Law Dictionary and one of the country’s leading authorities on legal writing and reasoning.3 The treatise is not a compendium of chap- ters written separately by these authors and loosely tied to a common ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Associate Professor of Law, University of Maine School of Law; Law Clerk to the Honorable Paul J. Watford, 2012–2013. Law Clerk to the Honorable Paul J. Watford, 2016–2017. In many chambers, judges work closely with their law clerks to resolve cases and draft opinions. -

The Socratic Method in the Age of Trauma

THE SOCRATIC METHOD IN THE AGE OF TRAUMA Jeannie Suk Gersen When I was a young girl, the careers I dreamed of — as a prima ballerina or piano virtuoso — involved performing before an audience. But even in my childhood ambitions of life on stage, no desire of mine involved speaking. My Korean immigrant family prized reading and the arts, but not oral expression or verbal assertiveness — perhaps even less so for girls. Education was the highest familial value, but a posture of learning anything worthwhile seemed to go together with not speak- ing. My incipient tendency to raise questions and arguments was treated as disrespect or hubris, to be stamped out, sometimes through punish- ment. As a result, and surely also due to natural shyness, I had an almost mute relation to the world. It was 1L year at Harvard Law School that changed my default mode from “silent” to “speak.” Having always been a student who said nothing and preferred a library to a classroom, I was terrified and scandalized as professors called on classmates daily to engage in back-and-forth dia- logues of reasons and arguments in response to questions, on subjects of which we knew little and on which we had no business expounding. What happened as I repeatedly faced my unwelcome turn, heard my voice, and got through with many stumbles was a revelation that changed my life. A light switched on. Soon, I was even volunteering to engage in this dialogue, and I was thinking more intensely, independently, and enjoyably than I ever had before. -

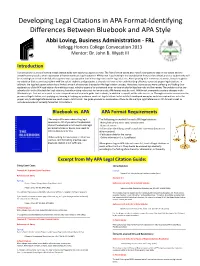

APA Format Requirements Bluebook Vs

Developing Legal Citations in APA Format‐Identifying Differences Between Bluebook and APA Style Abbi Loving, Business Administration ‐ FRL Kellogg Honors College Convocation 2013 Mentor: Dr. John B. Wyatt III Introduction I set out on the journey of writing a legal citation guide with two key purposes in mind. The first of which was to give myself a competitive edge in law school and the second was to provide a clear explanation of how to construct legal citations in APA format. Legal writing is the foundation of first year law school, and as a student who will be attending law school in the fall; this capstone was a preparation tool in learning how to write legal citations. After speaking with numerous attorneys, it was brought to my attention that a common problem with law school students and graduates is they do not have a clear understanding of how to construct proper legal citations. In addition, the legal education system has a limited amount of resources that explain the legal citation process. Resources I came across were confusing and lacking clear explanations of the APA legal citation formatting process, which is essential to understand when writing articles for legal journals and law review. The problem is that law schools refer to the Bluebook for legal citations, but when citing references for law journals, APA format must be used. APA format incorporates various changes in the Bluebook style. I set out on a quest to solve this problem and created a guide that students, in addition to myself, will be able to refer to. -

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Is Satisfaction Success? Evaluati

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Is Satisfaction Success? Evaluating Public Participation in Regulatory Policymaking Cary Coglianese September 2002 RWP02-038 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Is Satisfaction Success? Evaluating Public Participation in Regulatory Policymaking Cary Coglianese* Harvard University Dispute resolution seeks to find satisfactory solutions to conflicts, and researchers who evaluate dispute resolution procedures understandably want to consider whether disputants using these procedures are eventually satisfied with the resulting outcomes. A similar emphasis on satisfaction pervades the literature on techniques for resolving disputes and involving the public in regulatory policymaking. These techniques include the broad range of procedures and methods available to government for allowing input, feedback, and dialogue on regulatory policymaking, including comment solicitation, public hearings, workshops, dialogue groups, advisory committees, and negotiated rulemaking processes. Researchers evaluating these various techniques have often used participant satisfaction as a key evaluative criterion. While this criterion may seem suitable for evaluating private dispute resolution techniques, those who disagree in policy-making processes are not disputants in the same sense that landlords and tenants, creditors and debtors, or tortfeasors and victims are disputants in private life. Disputes in regulatory policymaking arise over public policy, not * Associate Professor of Public Policy and Chair of the Regulatory Policy Program, Harvard University, John F. -

Judge Amy Coney Barrett: Her Jurisprudence and Potential Impact on the Supreme Court

Judge Amy Coney Barrett: Her Jurisprudence and Potential Impact on the Supreme Court October 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46562 SUMMARY R46562 Judge Amy Coney Barrett: Her Jurisprudence October 6, 2020 and Potential Impact on the Supreme Court Valerie C. Brannon, On September 26, 2020, President Donald J. Trump announced the nomination of Judge Amy Coordinator Coney Barrett of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit to the Supreme Court of the Legislative Attorney United States to fill the vacancy left by the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on September 18, 2020. Judge Barrett has been a judge on the Seventh Circuit since November 2017, having Michael John Garcia, been nominated by President Trump and confirmed by the Senate earlier that year. The nominee Coordinator earned her law degree from Notre Dame Law School in 1997, and clerked for Judge Laurence H. Section Research Manager Silberman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. From 2002 until her appointment to the Seventh Circuit in 2017, Judge Barrett was a law professor at Notre Dame Law School, and she remains part of the law school faculty. Her Caitlain Devereaux Lewis, scholarship has focused on topics such as theories of constitutional interpretation, stare decisis, Coordinator and statutory interpretation. If confirmed, Judge Barrett would be the fifth woman to serve as a Section Research Manager Supreme Court Justice. During Judge Barrett’s September 26 Supreme Court nomination ceremony, she paid tribute to both Justice Ginsburg and her former mentor, Justice Scalia.