To-Do List: Athiest Ally Development Joseph Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Daniel Gasman

From Haeckel to Hitler: The Anatomy of a Controversy by Daniel Gasman IN BEN STEIN’S DOCUMENTARY FILM Expelled, the erstwhile game-show host and financial columnist attempted to link Darwin to Hitler and thereby condemn the scientific theory of evolution by association with the political theory of National Socialism. The film failed, fortunately, and was thoroughly panned by the critics. But in the cultural brouhaha stirred by the film’s release and subsequent disappearance from the big screen, not enough attention has been paid to whether or not there was a historical connection between the social Darwinists of the 19th century with the National Socialists of the 20th century. It turns out that there is, through the personage of the German biologist Ernst Haeckel; but a new biography of Haeckel, published shortly after Stein exited stage left, claims to rehabilitate Haeckel by disconnecting him from German social Darwinism, and thereby exonerating evolutionary theory. Unfortunately this new biography does no such thing, for in the end we must be true to the historical facts. Robert J. Richard’s The Tragic Sense of Life: Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle Over Evolutionary Thought2 promises to rescue Haeckel from a century and a half of disparaging assessments of his biology, and above all undertakes a refutation of the more recent and widely held belief that he was instrumental in formulating the basic tenets of Nazi ideology. The common understanding among historians about the connection between Haeckel and Hitler is this: Adolf Hitler (b. 1889) came of age during the decade and a half following the publication in 1899 of Ernst Haeckel’s Riddle of the Universe, a runaway best seller that over the next two or three decades sold more copies internationally than the Bible and profoundly shaped the consciousness of the modern world. -

San Jose Honors Jewish Lives

Wednesday, Volume 151 10.31.2018 No. 31 SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 WWW.SJSUNEWS.COM/SPARTAN_DAILY San Jose honors Jewish lives BEN STEIN | SPARTAN DAILY A participant holds up a sign outside of city hall during the Interfaith Vigil of Solidarity Against Hate on Tuesday. The vigil was to show solidarity with victims of Saturday’s shooting at Tree of Life Synogogue in Pittsburgh. District 5 County Supervisor Joe Members of the Jewish community, gogue in Pennsylvania,” Liccardo said. By Ben Stein Simitian said. elected officials and several interfaith “Today, Pittsburgh is the center of the The Jewish Federation of Silicon leaders spoke on the mass shooting and world,” he added. Eleven candles, representing the Valley set up the Interfaith Vigil of how everyone was affected, not only The speakers described their emo- 11 Jewish men and women killed in Solidarity Against Hate in sup- the Jewish community in Pittsburgh. tions and shared their thoughts follow- Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Congregation port of the Pittsburgh community. San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo ing the attack. Instead of placing shame synagogue on Saturday, were lit in Congregation Shir Hadash Cantor explained that when a tragedy occurs, on the suspect and other anti-Semitic front of the more than 500-person Devorah Felder-Levy led the group in the entire world pauses, not only the incidents, they offered solutions to crowd outside City Hall on Tuesday. “Gesher Tzar Meod,” a song that trans- affected community. make the world a better place. “We say each of their names so lates to “The whole world is a very “[The attack] has violated the sanc- “We can send cards and letters of they do not become just a statistic, narrow bridge, the important thing is tuary of holy places, whether it’s they will forever be remembered,” to not be afraid.” a church in Charleston or a syna- VIGIL | Page 2 Search for permanent UPD chief continues By Vicente Vera tive recruitment services,” STAFF WRITER said Regan Williams, senior vice president of Bob Murray & Associates. -

Was Hitler a Darwinian?

Was Hitler a Darwinian? Robert J. Richards The University of Chicago The Darwinian underpinnings of Nazi racial ideology are patently obvious. Hitler's chapter on "Nation and Race" in Mein Kampf discusses the racial struggle for existence in clear Darwinian terms. Richard Weikart, Historian, Cal. State, Stanislaus1 Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that's almost in shape of a camel? Shakespeare, Hamlet, III, 2. 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Issues regarding a Supposed Conceptually Causal Connection . 4 3. Darwinian Theory and Racial Hierarchy . 10 4. The Racial Ideology of Gobineau and Chamberlain . 16 5. Chamberlain and Hitler . 27 6. Mein Kampf . 29 7. Struggle for Existence . 37 8. The Political Sources of Hitler’s Anti-Semitism . 41 9. Ethics and Social Darwinism . 44 10. Was the Biological Community under Hitler Darwinian? . 46 11. Conclusion . 52 1. Introduction Several scholars and many religiously conservative thinkers have recently charged that Hitler’s ideas about race and racial struggle derived from the theories of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), either directly or through intermediate sources. So, for example, the historian Richard Weikart, in his book From Darwin to Hitler (2004), maintains: “No matter how crooked the road was from Darwin to Hitler, clearly Darwinism and eugenics smoothed the path for Nazi ideology, especially for the Nazi 1 Richard Weikart, “Was It Immoral for "Expelled" to Connect Darwinism and Nazi Racism?” (http://www.discovery.org/a/5069.) 1 stress on expansion, war, racial struggle, and racial extermination.”2 In a subsequent book, Hitler’s Ethic: The Nazi Pursuit of Evolutionary Progress (2009), Weikart argues that Darwin’s “evolutionary ethics drove him [Hitler] to engage in behavior that the rest of us consider abominable.”3 Other critics have also attempted to forge a strong link between Darwin’s theory and Hitler’s biological notions. -

Participation

PARTICIPATION A LOOK BACK AT 2007 Hinckley Institute Holds 2000th Hinckley Forum “OUR YOUNG, BEST MINDS MUST BE ENCOURAGED TO ENTER POLITICS.” Robert H. Hinckley 2 In This Issue Dr. J.D. Williams Page 3 Hinckley News Page 4 Internship Programs Page 8 Outstanding Interns Page 16 Scholarships Page 18 PARTICIPATION Hinckley Forums Page 20 Alumni Spotlights Page 25 Hinckley Staff Page 26 Donors Page 28 Hinckley Institute Holds 2000th Hinckley Forum Since 1965, the Hinckley Institute has held more than 2,000 Hinckley Forums (previously known as “Coffee & Politics”) featuring local, national, and international political leaders. Hinckley Forums provide University of Utah students and the surrounding community intimate access to and interaction with our nation’s leaders. Under the direction of Hinck- ley Institute assistant director Jayne Nelson, the Hinckley Institute hosts 65-75 forums each year in the newly renovated Hinckley Caucus Room. Partnerships with supporting Univer- sity of Utah colleges and departments, local radio and news stations, our generous donors, and the Sam Rich Program in International Politics ensure the continued success of the Hinckley Forums program. University of Utah students can now receive credit for attend- ing Hinckley Forums by enrolling in the Political Forum Series course (Political Science 3910). All Hinckley Forums are free and open to the public. For a detailed listing of 2007 Hinckley Forums, refer to pages 20 – 24. Past Hinckley Forum Guests Prince Turki Al-Faisal Archibald Cox Edward Kennedy Frank Moss Karl Rove Al Saud Russ Feingold William Lawrence Ralph Nader Larry Sabato Norman Bangerter Gerald Ford Michael Leavitt Richard Neustadt Brian Schweitzer Robert Bennett Jake Garn Richard Lugar Dallin H. -

Todd Buchholz Economist Todd Buchholz “Lights up Economics with a Wickedly Sparkling Wit,” Says the Associated Press. the Fo

Todd Buchholz Economist Todd Buchholz “lights up economics with a wickedly sparkling wit,” says the Associated Press. The former White House senior economic advisor, Tiger hedge fund managing director and best-selling author has jousted with such personalities as James Carville and Ben Stein. His lively and informative speaking engagements have earned him a place in Successful Meetings Magazine’s “21 Top Speakers for the 21st Century, and his best-selling books on economics and financial markets have been widely translated and are taught in universities worldwide. As a frequent commentator on the state of the markets, Todd Buchholz brings his experience as a former White House director of economic policy, a managing director of the $15 billion Tiger hedge fund, and a Harvard economics teacher to the cutting edge of economics, fiscal politics, finance, and business strategy. Buchholz is a frequent guest on ABC News, PBS, and CBS, and he recently hosted his own special on CNBC. Buchholz has debated such luminaries in the field as Lester Thurow and Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz. Before joining Tiger in 1996, Buchholz was President of the G7 Group, Inc, an international consulting firm whose clientele included many of the top securities firms, investment banks and money managers in New York, London, and Tokyo, including Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. His commentaries were closely read by officials at the Federal Reserve, Bundesbank and Bank of England. From 1989 to 1992 he served at the White House as a Director for Economic Policy. Buchholz won the Allyn Young Teaching Prize at Harvard and holds advanced degrees in economics and law from Cambridge and Harvard. -

Amazon.Com: Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed: Ben Stein, Richard Da

Amazon.com: Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed: Ben Stein, Richard Da... http://www.amazon.com/Expelled-Intelligence-Allowed-Ben-Stein/dp/B... Link to this page Add to aStore Your Earnings Summary What's New Discussion Boards Settings Hello, Robert J II Marks. We have recommendations for you. (Not Robert?) Robert's Amazon.com Today's Deals Gifts & Wish Lists Gift Cards Your Account | Help Movies & TV Advanced Search Browse Genres New Releases Bestsellers DVD Deals TV Central Blu-ray Video On Demand First To Know™ Instant Order Update for Robert J II Marks. You purchased this item on October 5, 2008. View this order. Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed (2008) Quantity: Starring: Ben Stein, Richard Dawkins Director: Nathan Frankowski Rating: Format: or (240 customer reviews) Sign in to turn on 1-Click ordering. List Price: $26.99 or Price: $17.99 & eligible for FREE Super Saver Shipping on orders over $25. Details You Save: $9.00 (33%) Amazon Prime Free Trial required. Sign up when you Special Offers Available check out. Learn More Pre-order Price Guarantee. Learn more. This title will be released on October 21, 2008. Pre-order now! See larger image Ships from and sold by Amazon.com. Gift-wrap available. Save up to 60% in the Grab Bag Sale For a limited time, take advantage of big savings on everything from hit recent releases to TV favorites, documentaries and more. › See more product promotions Share with Friends Special Offers and Product Promotions Pre-order Price Guarantee! Order now and if the Amazon.com price decreases between your order time and the end of the day of the release date, you'll receive the lowest price. -

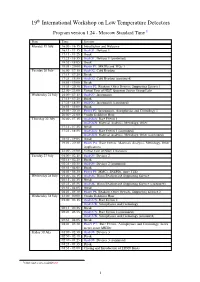

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - Moscow Standard Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 16:00 - 16:15 Introduction and Welcome 16:15 - 17:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O3: Instruments 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 20:00 - 21:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Tuesday 27 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 03:55 - 04:05 Break 04:05 - 05:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Wednesday 28 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting -

Inside Look Inspiration Remember

TrumanLibrary.org TRUMAN LIBRARY INSTITUTE INSIDE LOOK INSPIRATION REMEMBER Preview highlights from Meet an ambitious young Read the hometown the Truman Library’s new historian who has grown newspaper’s inspiring Korean War collection up with the Truman memorial to the 33rd in a behind-the-scenes Library’s educational president on the anniver- glimpse. 06 programs. 08 sary of his death. 10 THE ANNUAL DONOR ISSUE WINTER 2018-19 ADVANCING PRESIDENT TRUMAN’S LIBRARY AND LEGACY TRU MAGAZINE THE ANNUAL DONOR ISSUE | WINTER 2018-19 COVER: President Harry S. Truman at the rear of the Ferdinand Magellan train car during Winston Churchill’s visit to Fulton, Missouri, in 1946. Whistle Stop “I’d rather have lasting peace in the world than be president. I wish for peace, I work for peace, and I pray for peace continually.” CONTENTS Highlights 10 12 16 Remembering the 33rd President Harry Truman and Israel Thank You, Donors A look back on Harry Truman’s hometown Dr. Kurt Graham recounts the monumental history A note of gratitude to the generous members and newspaper’s touching memorial of the president. of Truman’s recognition of Israel. donors who are carrying Truman’s legacy forward. TrumanLibraryInstitute.org TRUMAN LIBRARY INSTITUTE 1 MESSAGE FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2018 was an auspicious year for Truman anniversaries: 100 years since Captain Truman’s service in World War I and 70 years since some of President Truman’s greatest decisions. These life-changing experiences and pivotal chapters in Truman’s story provided the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum with many meaningful opportunities to examine, contemplate and celebrate the legacy of our nation’s 33rd president. -

Response to This Article About the Hasbro/Discovery Hub Shift In

Response to this article about the Hasbro/Discovery Hub shift in power...which turned into another my long-winded, thoughtful rants: http://online.wsj.com/articles/discovery-to-take-control-of-the-hub-network- 1410979842 Well, that's...somewhat shocking. From what I can tell, the Hasbro/Discovery partnership in The Hub has been an amazing success. I watch the channel almost every day. Most of its programming is--and has been, for the past 3.5 years--excellent. From the original series (FiM, Pound Puppies, Strawberry Shortcake, LPS, Dan Vs., Aquabats Super Show, Family Game Night, Care Bears, Transformers, Haunting Hour), to all the other wonderful shows/sitcoms (oh my goodness!! Tiny Toon Adventures, Animaniacs, Goosebumps, Laverne & Shirley, Happy Days, Mork & Mindy, Step By Step, Who's the Boss, Family Ties, The Facts of Life, Sister, Sister, Sabrina, Atomic Betty, etc.), to the extremely well-chosen family movies (I loved it when they aired the Homeward Bound films, All Dogs Go to Heaven 2...today I saw Spaceballs...and they've just made so many other great movie picks every season.) They've been an outstanding example of listening to your viewers and giving them what they want. Even their misfires and middle-of-the-road shows are more than bearable (SheZow, animated Sabrina, Teenage Fairytale Dropouts, Kid President, Parents Just Don't Understand, and such.) If Hasbro were to grow dissatisfied with controlling six hours of its toy-based cartoons daily on Hub (which seems like a fair deal they've cut, tbh), and moved them over to Cartoon Network or Disney...well, at least the shows would still continue on, and be a MASSIVE boon to either of those channels. -

Managing Retirement Assets: Ensuring Seniors Don’T Outlive Their Savings

S. HRG. 109–638 MANAGING RETIREMENT ASSETS: ENSURING SENIORS DON’T OUTLIVE THEIR SAVINGS HEARING BEFORE THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON AGING UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION WASHINGTON, DC JUNE 21, 2006 Serial No. 109–25 Printed for the use of the Special Committee on Aging ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 30–042 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:00 Nov 01, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\DOCS\30042.TXT SAGING1 PsN: JOYCE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON AGING GORDON SMITH, Oregon, Chairman RICHARD SHELBY, Alabama HERB KOHL, Wisconsin SUSAN COLLINS, Maine JAMES M. JEFFORDS, Vermont JAMES M. TALENT, Missouri RON WYDEN, Oregon ELIZABETH DOLE, North Carolina BLANCHE L. LINCOLN, Arkansas MEL MARTINEZ, Florida EVAN BAYH, Indiana LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware RICK SANTORUM, Pennsylvania BILL NELSON, Florida CONRAD BURNS, Montana HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON, New York LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee KEN SALAZAR, Colorado JIM DEMINT, South Carolina CATHERINE FINLEY, Staff Director JULIE COHEN, Ranking Member Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:00 Nov 01, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 H:\DOCS\30042.TXT SAGING1 PsN: JOYCE C O N T E N T S Page Opening Statement of Senator Gordon Smith ....................................................... 1 Opening Statement of Senator Herb Kohl ............................................................. 2 Opening Statement of Senator Ken Salazar ........................................................ -

Ben Stein's Trojan Horse

Ben Stein’s Trojan Horse Mobilizing the State House and Local News Agenda MATTHEW C. NISBET ack in April 2008, as the docu- mentary Expelled: No Intelligence BAllowed premiered in more than 1,000 theaters across the country, I gath- ered with friends for a Friday-evening screening in downtown Washington, D.C. The medium-sized Regal Cinemas theater was about 80 percent full, with an audi- ence that appeared to be the typical urban professional crowd for the surrounding arts and entertainment district, a demographic that is more likely to read the New York Times at a coffee house on Sunday than to attend church. As I watched the film and monitored audience reaction, I grew convinced that although Expelled’s claims have been thor- oughly debunked (NCSE 2008; Scientific American 2008; see also the critique in SI, May/June 2008 by Dan Whipple and Nathan Bupp’s piece in SI, July/ August 2008), the documentary’s long- term impact remains dangerously under- estimated. In the film, the comedic actor Ben Stein plays the role of a conservative Michael As I watched the film and monitored Moore, taking viewers on an investigative journey into the realm of “Big Science,” audience reaction, I grew convinced that an institution in which, Stein concludes, although Expelled’s claims have been thoroughly “scientists are not allowed to even think thoughts that involve an intelligent cre- debunked, the documentary’s long-term impact ator.” Expelled outrageously suggests that remains dangerously underestimated. Darwinism, as Stein calls evolution, led to the Holocaust. He also suggests that scientists have been denied tenure and that research has been suppressed, all in the common to political advertising.