The Nature of Quantification of High-Degree: 'Very', 'Many', and the Exclamative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Performing Gender: Hell Hath No Fury Like a Woman Horned a Thesis Submitted to the Gradu

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE PERFORMING GENDER: HELL HATH NO FURY LIKE A WOMAN HORNED A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By GLENN FLANSBURG Norman, Oklahoma 2021 PERFORMING GENDER: HELL HATH NO FURY LIKE A WOMAN HORNED A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE GAYLORD COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. Ralph Beliveau, Chair Dr. Meta Carstarphen Dr. Casey Gerber © Copyright by GLENN FLANSBURG 2021 All Rights Reserved. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... vi Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Heavy Metal Reigns…and Quickly Dies ....................................................................................... 1 Music as Discourse ...................................................................................................................... 2 The Hegemony of Heavy Metal .................................................................................................. 2 Theory ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Encoding/Decoding Theory ..................................................................................................... 3 Feminist Communication -

Within Temptation Black Symphony 1080P Torrent

1 / 3 Within Temptation Black Symphony 1080p Torrent Within Temptation In Vain Single Edit 2019 Within Temptation 2014 Let Us Burn Elements & Hydra Live in Concert FLAC Within Temptation ... Within.Temptation.Black.Symphony.2008.BDRip.720p.DTS, 4.35GB, March 2019 ... XXX.1080p.. Within.Temptation-Black.Symphony [2008][BDrip][1080p][x264]. http://www.youtube.com/v/N74dKIauGPs&feature=player_embedded#!. An Easier Way to Record Audio to MP3 FLAC is registered with the Charities ... is the second studio album by Dutch symphonic metal band Within Temptation.. Re: Torrent within temptation black symphony mp3. Grupo da fábrica não nasceu bonita mp3 download. Hentai porno flash pornô download jogos grátis.. Roku finally gets into 4K with new streaming box, updated. Amazon.com: A Passage to India: David Lean: ... Within Temptation Black Symphony 1080p Torrent.. Results 1 - 32 — within temptation black symphony 2008 bluray 720p megapart02 (2G) ... within temptation black symphony 1080p bray x264 part01 (209.71M) .... pred 4 dňami — We are J- Pop lovers who want to share with you all we have. ... jpop jpop いい歌 flac rar jpop jpop flac torrent Convulse – World Without .... The gothic rock band "Within Temptation" stages their most ambitious concert to date at Rotterdam's Ahoy Arena in Feb 2008. Dubbed 'Black Symphony', the .... Within Temptation - The Metropole Orchestra Black Symphony.flac.cue ... concert HD Hydra tour 2014 - Halle Tony Garnier (Lyon) - April 24th, 2014[1080P].MP4. Files: 1, Size: 10.04 GB, Se: 2, Le: 0, Category: Music, Uploader: oleg-1937, Download added: 8 years ago, Updated: 18-Jun-2021.. 6710 items — Temptation (1957 Kô Nakahira - WEBRip 1080p x265 AAC EngSub).mkv .. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Lyrics and Sources

LYRICS AND SOURCES VOLUME 1: GIRLS IN TROUBLE VOLUME 2: HALF YOU HALF ME VOLUME 3: OPEN THE GROUND by Alicia Jo Rabins GIRLS IN TROUBLE is a song cycle about the complicated lives of Biblical women by poet, Torah scholar, musician and performer Alicia Jo Rabins. GIRLS IN TROUBLE is also a touring band (ranging from Alicia solo to a four-piece with drums) which performs these songs live in rock clubs, synagogues, universities, and living rooms and has received praise from the Huffington Post, the New Yorker, LA Weekly, Popmatters, Largeheartedboy.com, and the Chicago Reader. The GIRLS IN TROUBLE CURRICULUM is a series of in-depth study guides about women in Torah through art, created by musician and Jewish educator Alicia Jo Rabins. These study guides focus on how stories of women in Torah reflect the complexity of our own lives, and how art can help us deepen our connections to these ancient texts. This booklet contains lyrics and notes about sources from Girls in Trouble’s trilogy of albums: “GIRLS IN TROUBLE,” “HALF YOU HALF ME,” and “OPEN THE GROUND.” All lyrics © Alicia Jo Rabins. Reprinting by permission only. For more information, study guides, and Girls in Trouble tour dates, please visit www.girlsintroublemusic.com. For booking Alicia and Girls in Trouble for performing and teaching engagements, or to contact Alicia, please write [email protected]. Dedicated to Aaron Hartman. Song by Girls in Trouble 2 © Lyrics & Music by Alicia Jo Rabins (BMI) www.girlsintroublemusic.com TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I: GIRLS IN TROUBLE -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

B.Z.N. Video Opnamen

BZN TV-LIJST 1966 – 2018 BZN TV SPECIALS BZN TV SPECIALS (1/13) No. Programma Datum Uit Liedjes Tijdsduur Bron 001a. Making a name / BZN in Frankrijk 02/09/77 In my heart (opgenomen in studio) + N1700 (TROS) Dreamin’ (opgenomen in studio) + Mon Amour (in Monaco) * + * (ook op DVD SINGLES COLLECTION) * (ook op DVD MOMENTS IN TIME) Montmartre (in Parijs Montmartre) + L’adieu (in Monaco/Nice, in Parijs bij Eiffeltoren en in de studio) + Sevilla (in de studio) (studio wrs. opgenomen op 27/08/77?) N.B. in deze special en clips heeft Anny d’r voet in het gips 23:21 001b. Making a name / BZN in Frankrijk 02/09/77 Mon Amour (in Monaco) Uit Beeld & (TROS) Montmartre (in Parijs Montmartre) Geluid Archief L’adieu (in Monaco/Nice, in Parijs bij Eiffeltoren, instrumental loopt langer door bij Eiffeltoren maar eind van het lied is zwart, waar de special teruggaat naar de studio) 11:27 002. You’re Welcome / BZN in Tenerife 15/06/78 Sailing + Play the mandoline + Uit TROS (TROS) Vive l’amour + Lady McCorey * Archief * (ook op DVD SINGLES COLLECTION) + Just take my hand + Don’t break my heart + Hey Mister 26:44 003. Summer Fantasy / BZN in Holland 16/08/79 Summernights + Drink the wine + N1700 (Hoorn / Middelie / Enkhuizen / 18/01/80 Oh me oh my + Dreamland + Scheveningen / Volendam) Marching on + Singing in the rain + (NCRV) A la campagne + interviews met de BZN leden over hun vroegere vak 25:41 004. Green Valleys / BZN in Schotland 27/09/80 Yellow rose + The valley + N1700 (NCRV) 20/06/81 Rockin’ the trolls * * (ook op DVD SINGLES COLLECTION) + May we always be together + Goodnight + Red balloon aftiteling origineel van onder naar boven, 24:45 aftiteling herh. -

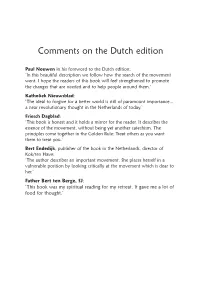

Comments on the Dutch Edition

Comments on the Dutch edition Paul Nouwen in his foreword to the Dutch edition: ‘In this beautiful description we follow how the search of the movement went. I hope the readers of this book will feel strengthened to promote the changes that are needed and to help people around them.’ Katholiek Nieuwsblad: ‘The ideal to forgive for a better world is still of paramount importance... a near revolutionary thought in the Netherlands of today.’ Friesch Dagblad: ‘This book is honest and it holds a mirror for the reader. It describes the essence of the movement, without being yet another catechism. The principles come together in the Golden Rule: Treat others as you want them to treat you.’ Bert Endedijk, publisher of the book in the Netherlands, director of Kok/ten Have: ‘The author describes an important movement. She places herself in a vulnerable position by looking critically at the movement which is dear to her.’ Father Bert ten Berge, SJ: ‘This book was my spiritual reading for my retreat. It gave me a lot of food for thought.’ Reaching for a new world Initiatives of Change seen through a Dutch window Hennie de Pous-de Jonge CAUX BOOKS First published in 2005 as Reiken naar een nieuwe wereld by Uitgeverij Kok – Kampen The Netherlands This English edition published 2009 by Caux Books Caux Books Rue de Panorama 1824 Caux Switzerland © Hennie de Pous-de Jonge 2009 ISBN 978-2-88037-520-1 Designed and typeset in 10.75pt Sabon by Blair Cummock Printed by Imprimerie Pot, 78 Av. des Communes-Réunies, 1212 Grand-Lancy, Switzerland Contents Preface -

The Ultimate Playlist This List Comprises More Than 3000 Songs (Song Titles), Which Have Been Released Between 1931 and 2018, Ei

The Ultimate Playlist This list comprises more than 3000 songs (song titles), which have been released between 1931 and 2021, either as a single or as a track of an album. However, one has to keep in mind that more than 300000 songs have been listed in music charts worldwide since the beginning of the 20th century [web: http://tsort.info/music/charts.htm]. Therefore, the present selection of songs is obviously solely a small and subjective cross-section of the most successful songs in the history of modern music. Band / Musician Song Title Released A Flock of Seagulls I ran 1982 Wishing 1983 Aaliyah Are you that somebody 1998 Back and forth 1994 More than a woman 2001 One in a million 1996 Rock the boat 2001 Try again 2000 ABBA Chiquitita 1979 Dancing queen 1976 Does your mother know? 1979 Eagle 1978 Fernando 1976 Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! 1979 Honey, honey 1974 Knowing me knowing you 1977 Lay all your love on me 1980 Mamma mia 1975 Money, money, money 1976 People need love 1973 Ring ring 1973 S.O.S. 1975 Super trouper 1980 Take a chance on me 1977 Thank you for the music 1983 The winner takes it all 1980 Voulez-Vous 1979 Waterloo 1974 ABC The look of love 1980 AC/DC Baby please don’t go 1975 Back in black 1980 Down payment blues 1978 Hells bells 1980 Highway to hell 1979 It’s a long way to the top 1975 Jail break 1976 Let me put my love into you 1980 Let there be rock 1977 Live wire 1975 Love hungry man 1979 Night prowler 1979 Ride on 1976 Rock’n roll damnation 1978 Author: Thomas Jüstel -1- Rock’n roll train 2008 Rock or bust 2014 Sin city 1978 Soul stripper 1974 Squealer 1976 T.N.T. -

Realms of Fantasy Dec 2010

The WyndMaster's Lady The WyndMaster's Son Srae Iss-Ka-Mala A Dream of Drowned Hollow Nexus Point Motor City Fae Author: Charlotte Boyett~Compo Author: Charlotte Boyett~Compo Author: Chaeya Author: Lee Barwood Author: Jaleta Clegg Author: Cindy Spencer Pape www.windlegends.org www.windlegends.org www.electricgentlemen.com www.leebarwood.com www.jaletac.com www.cindyspencerpape.com Background Images Courtesy Of: © 2010 STScI & NASA Bloodsworn: Bound by Magic Mudflat Spice and Sorcery Blood of the Dark Moon A Bloody Good Cruise Author: Kathy Lane Author: Phoebe Matthews Author: Adrianne Brennan Author: Diana Rubino www.kyrlane.com www.phoebematthews.com www.adriannebrennan.com www.dianarubino.com Resurrection Code Second Night: More Fairy Tales Retold Some Cost a Passing Bell On the Wild Side Heartstone Shadows of the Soul Author: Lyda Morehouse Author: Caroline Aubrey Author: Lee Barwood Author: Gerri Bowen Author: Lynda K. Scott Author: Angelique Armae www.lydamorehouse.com www.carolineaubrey.net www.leebarwood.com www.gerribowen.com www.lyndakscott.com www.angeliquearmae.com INFINITE WORLDS OF FANTASY AUTHORS IMAGINATION UNRESTRICTED BY REALITY The WyndMaster's Lady The WyndMaster's Son Srae Iss-Ka-Mala A Dream of Drowned Hollow Nexus Point Motor City Fae Author: Charlotte Boyett~Compo Author: Charlotte Boyett~Compo Author: Chaeya Author: Lee Barwood Author: Jaleta Clegg Author: Cindy Spencer Pape www.windlegends.org www.windlegends.org www.electricgentlemen.com www.leebarwood.com www.jaletac.com www.cindyspencerpape.com Background Images -

Songs by Title

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Title www.adj2.com Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly A Dozen Roses Monica (I Got That) Boom Boom Britney Spears & Ying Yang Twins A Heady Tale Fratellis, The (I Just Wanna) Fly Sugar Ray A House Is Not A Home Luther Vandross (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra A Long Walk Jill Scott + 1 Martin Solveig & Sam White A Man Without Love Englebert Humperdinck 1 2 3 Miami Sound Machine A Matter Of Trust Billy Joel 1 2 3 4 I Love You Plain White T's A Milli Lil Wayne 1 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott A Moment Like This,zip Leona 1 Thing Amerie A Moument Like This Kelly Clarkson 10 Million People Example A Mover El Cu La Sonora Dinamita 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay, Justin Bieber A Night To Remember High School Musical 3 10,000 Nights Alphabeat A Song For Mama Boyz Ii Men 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters A Sunday Kind Of Love Reba McEntire 12 Days Of X Various A Team, The Ed Sheeran 123 Gloria Estefan A Thin Line Between Love & Hate H-Town 1234 Feist A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton 16 @ War Karina A Thousand Years Christina Perri 17 Forever Metro Station A Whole New World Zayn, Zhavia Ward 19-2000 Gorillaz ABC Jackson 5 1973 James Blunt Abc 123 Levert 1982 Randy Travis Abide With Me West Angeles Gogic 1985 Bowling For Soup About A Girl Sugababes 1999 Prince About You Now Sugababes 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The Abracadabra Steve Miller Band 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Nine Days 20 Years Ago Kenny Rogers Acapella Kelis 21 Guns Green Day According To You Orianthi 21 Questions 50 Cent Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus 21st Century Breakdown Green Day Act A Fool Ludacris 21st Century Girl Willow Smith Actos De Un Tonto Conjunto Primavera 22 Lily Allen Adam Ant Goody Two Shoes 22 Taylor Swift Adams Song Blink 182 24K Magic Bruno Mars Addicted To You Avicii 29 Palms Robert Plant Addictive Truth Hurts & Rakim 2U David Guetta Ft. -

PROJECT SUPERMAN PROJECT SUPERMAN a "VICTIM" of the ILLUMINATI's SUPER-RACE PROJECTS & MONTAUK EXPERIMENTS SPEAKS out {The Andy Pero Story, Aka Mr.X

PROJECT SUPERMAN PROJECT SUPERMAN A "VICTIM" OF THE ILLUMINATI'S SUPER-RACE PROJECTS & MONTAUK EXPERIMENTS SPEAKS OUT {the Andy Pero story, aka Mr.X... Nazi Mind control and the Montauk Projects...} Introduction Memories are a strange thing, there are tangible memories that can be proven factually, there are suppressed memories which are clouded recollections of actual events, memories that are a mixture of real and unreal events, memories based on imagination and possibly most frightening of all, memories that have been intentionally "programmed" within the mind of a person, which might consist of anything between actual real life experiences to entirely "designer" memories that may have been inserted to "cover up" experiences that are far more stranger than fiction. Just where in the spectrum the experiences of Andy Pero may fit, I do not know exactly, although many of the places and people he describes DO exist as evidenced by the links that I've added... so at least a good number of his memories are apparently accurate... but the question is, are his reported experiences with the alien time/space projects as carried out in the Montauk bases also based on fact, and if so to what degree? Others have made similar claims about montauk {although these fantastic experiences do not appear until the last few sections of Andy's story} as can be seen by doing a SEARCH of the Internet for other writings on the Montauk Project. So here then -- for those very few readers who will view this page -- is Andy Pero's story... - Alan ********************* This is my story, and this is my life. -

The Evolution of Dutch American Identities, 1847-Present Michael J

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Evolution of Dutch American Identities, 1847-Present Michael J. Douma Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE EVOLUTION OF DUTCH AMERICAN IDENTITIES, 1847-PRESENT By MICHAEL J. DOUMA A Dissertation submitted to the History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 i The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Michael J. Douma defended on March 18, 2011. _____________________________ Dr. Suzanne Sinke Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Dr. Reinier Leushuis University Representative ______________________________ Dr. Edward Gray Committee Member ______________________________ Dr. Jennifer Koslow Committee Member ______________________________ Dr. Darrin McMahon Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation was written on napkins, the reverse sides of archival call slips and grocery receipts, on notebook paper while sitting in the train, in Dutch but mostly in English, in long-hand, scribble, and digital text. Most of the chapters were composed in a fourth floor apartment on the west side of Amsterdam in the sunless winter of 2009-2010 and the slightly less gloomy spring of 2010. Distractions from the work included Sudoku puzzles, European girls, and Eurosport broadcasts of the Winter Olympics on a used television with a recurring sound glitch. This dissertation is the product of my mind and its faults are my responsibility, but the final product represents the work and activity of many who helped me along the way.