Regional Frames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Road Movies of the 1960S, 1970S, and 1990S

Identity and Marginality on the Road: American Road Movies of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1990s Alan Hui-Bon-Hoa Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal March 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies. © Alan Hui-Bon-Hoa 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Abrégé …………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Acknowledgements …..………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Chapter One: The Founding of the Contemporary Road Rebel …...………………………...… 23 Chapter Two: Cynicism on the Road …………………………………………………………... 41 Chapter Three: The Minority Road Movie …………………………………………………….. 62 Chapter Four: New Directions …………………………………………………………………. 84 Works Cited …………………………………………………………………………………..... 90 Filmography ……………………………………………………………………………………. 93 2 Abstract This thesis examines two key periods in the American road movie genre with a particular emphasis on formations of identity as they are articulated through themes of marginality, freedom, and rebellion. The first period, what I term the "founding" period of the road movie genre, includes six films of the 1960s and 1970s: Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider (1969), Francis Ford Coppola's The Rain People (1969), Monte Hellman's Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Richard Sarafian's Vanishing Point (1971), and Joseph Strick's Road Movie (1974). The second period of the genre, what I identify as that -

Diciembreenlace Externo, Se Abre En

F I L M O T E C A E S P A Ñ O L A Sede: Cine Doré C/ Magdalena nº 10 c/ Santa Isabel, 3 28012 Madrid 28012 Madrid Telf.: 91 4672600 Telf.: 91 3691125 Fax: 91 4672611 (taquilla) [email protected] 91 369 2118 http://www.mcu.es/cine/MC/FE/index.html (gerencia) Fax: 91 3691250 MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Precio: Normal: 2,50€ por sesión y sala 20,00€ abono de 10 PROGRAMACIÓN sesiones. Estudiante: 2,00€ por sesión y sala diciembre 15,00€ abono de 10 sesiones. 2009 Horario de taquilla: 16.15 h. hasta 15 minutos después del comienzo de la última sesión. Venta anticipada: 21.00 h. hasta cierre de la taquilla para las sesiones del día siguiente hasta un tercio del aforo. Horario de cafetería: 16.45 - 00.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 49 23 Horario de librería: 17.00 - 22.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 46 73 Lunes cerrado (*) Subtitulaje electrónico DICIEMBRE 2009 Monte Hellman Dario Argento Cine para todos - Especial Navidad Charles Chaplin (I) El nuevo documental iberoamericano 2000-2008 (I) La comedia cinematográfica española (II) Premios Goya (y V) El Goethe-Institut Madrid presenta: Ulrike Ottinger Buzón de sugerencias Muestra de cortometrajes de la PNR Las sesiones anunciadas pueden sufrir cambios debido a la diversidad de la procedencia de las películas programadas. Las copias que se exhiben son las de mejor calidad disponibles. Las duraciones que figuran en el programa son aproximadas. Los títulos originales de las películas y los de su distribución en España figuran en negrita. -

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960S Promotional Featurettes

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960s Promotional Featurettes by DANIEL STEINHART Abstract: Before making-of documentaries became a regular part of home-video special features, 1960s promotional featurettes brought the public a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood’s production process. Based on historical evidence, this article explores the changes in Hollywood promotions when studios broadcasted these featurettes on television to market theatrical films and contracted out promotional campaigns to boutique advertising agencies. The making-of form matured in the 1960s as featurettes helped solidify some enduring conventions about the portrayal of filmmaking. Ultimately, featurettes serve as important paratexts for understanding how Hollywood’s global production work was promoted during a time of industry transition. aking-of documentaries have long made Hollywood’s flm production pro- cess visible to the public. Before becoming a staple of DVD and Blu-ray spe- M cial features, early forms of making-ofs gave audiences a view of the inner workings of Hollywood flmmaking and movie companies. Shortly after its formation, 20th Century-Fox produced in 1936 a flmed studio tour that exhibited the company’s diferent departments on the studio lot, a key feature of Hollywood’s detailed division of labor. Even as studio-tour short subjects became less common because of the restructuring of studio operations after the 1948 antitrust Paramount Case, long-form trailers still conveyed behind-the-scenes information. In a trailer for The Ten Commandments (1956), director Cecil B. DeMille speaks from a library set and discusses the importance of foreign location shooting, recounting how he shot the flm in the actual Egyptian locales where Moses once walked (see Figure 1). -

Downloaded from by Guest on 26 June 2020

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Crime Fiction and Black Criminality Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8zw7q50m Author Martin, Theodore Publication Date 2018-10-17 DOI 10.1093/alh/ajy037 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Crime Fiction and Black Criminality Theodore Martin* Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/alh/article-abstract/30/4/703/5134081 by guest on 26 June 2020 Nor was I up to being both criminal and detective—though why criminal Ididn’tknow. Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man 1. The Criminal Type A remarkable number of US literature’s most recognizable criminals reside in mid-twentieth-century fiction. Between 1934 and 1958, James M. Cain gave us Frank Chambers and Walter Huff; Patricia Highsmith gave us Charles Bruno and Tom Ripley; Richard Wright gave us Bigger Thomas and Cross Damon; Jim Thompson gave us Lou Ford and Doc McCoy; Dorothy B. Hughes gave us Dix Steele. Many other once-estimable authors of the middle decades of the century—like Horace McCoy, Vera Caspary, Charles Willeford, and Willard Motley—wrote novels centrally concerned with what it felt like to be a criminal. What, it is only natural to wonder, was this midcentury preoccupation with crime all about? Consider what midcentury crime fiction was not about: detec- tives. Although scholars of twentieth-century US literature often use the phrases crime fiction and detective fiction interchangeably, the detective and the criminal were, by midcentury, the anchoring pro- tagonists of two distinct genres. While hardboiled detectives contin- ued to dominate the literary marketplace of pulp magazines and paperback originals in the 1940s and 1950s, they were soon accom- panied on the shelves by a different kind of crime fiction, which was *Theodore Martin is Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of Contemporary Drift: Genre, Historicism, and the Problem of the Present (Columbia UP, 2017). -

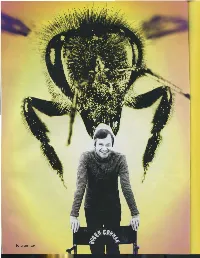

30 MENTAL FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA by IAN LENDLER

30 MENTAL_FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA BY IAN LENDLER MENTALFLOSS.COM 31 the Golden Age of Hollywood, big-budget movies were classy affairs, full of artful scripts and classically trained actors. And boy, were they dull. Then came Roger Corman, the King of the B-Movies. With Corman behind the camera, motorcycle gangs and mutant sea creatures .filled the silver screen. And just like that, movies became a lot more fun. .,_ Escape from Detroit For someone who devoted his entire life to creating lurid films, you'd expect Roger Corman's biography to be the stuff of tab loid legend. But in reality, he was a straight-laced workaholic. Having produced more than 300 films and directed more than 50, Corman's mantra was simple: Make it fast and make it cheap. And certainly, his dizzying pace and eye for the bottom line paid off. Today, Corman is hailed as one of the world's most prolific and successful filmmakers. But Roger Corman didn't always want to be a director. Growing up in Detroit in the 1920s, he aspired to become an engineer like his father. Then, at age 14, his ambitions took a turn when his family moved to Los Angeles. Corman began attending Beverly Hills High, where Hollywood gossip was a natural part of the lunchroom chatter. Although the film world piqued his interest Corman stuck to his plan. He dutifully went to Stanford and earned a degree in engineering, which he didn't particularly want. Then he dutifully entered the Navy for three years, which he didn't particularly enjoy. -

WED 5 SEP Home Home Box Office Mcr

THE DARK PAGESUN 5 AUG – WED 5 SEP home home box office mcr. 0161 200 1500 org The Killing, 1956 Elmore Leonard (1925 – 2013) The Killer Inside Me being undoubtedly the most Born in Dallas but relocating to Detroit early in his faithful. My favourite Thompson adaptation is Maggie A BRIEF NOTE ON THE GLOSSARY OF life and becoming synonymous with the city, Elmore Greenwald’s The Kill-Off, a film I tried desperately hard Leonard began writing after studying literature and to track down for this season. We include here instead FILM SELECTIONS FEATURED WRITERS leaving the navy. Initially working in the western genre Kubrick’s The Killing, a commissioned adaptation of in the 1950s (Valdez Is Coming, Hombre and Three- Lionel White’s Clean Break. The best way to think of this season is perhaps Here is a very brief snapshot of all the writers included Ten To Yuma were all filmed), Leonard switched to Raymond Chandler (1888 – 1959) in the manner of a music compilation that offers in the season. For further reading it is very much worth crime fiction and became one of the most prolific and a career overview with some hits, a couple of seeking out Into The Badlands by John Williams, a vital Chandler had an immense stylistic influence on acclaimed practitioners of the genre. Martin Amis and B-sides and a few lesser-known curiosities and mix of literary criticism, geography, politics and author American popular literature, and is considered by many Stephen King were both evangelical in their praise of his outtakes. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Join Us. 100% Sirena Quality Taste 100% Pole & Line

melbourne february 8–22 march 1–15 playing with cinémathèque marcello contradiction: the indomitable MELBOURNE CINÉMATHÈQUE 2017 SCREENINGS mastroianni, isabelle huppert Wednesdays from 7pm at ACMI Federation Square, Melbourne screenings 20th-century February 8 February 15 February 22 March 1 March 8 March 15 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm Presented by the Melbourne Cinémathèque man WHITE NIGHTS DIVORCE ITALIAN STYLE A SPECIAL DAY LOULOU THE LACEMAKER EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Luchino Visconti (1957) Pietro Germi (1961) Ettore Scola (1977) Maurice Pialat (1980) Claude Goretta (1977) Jean-Luc Godard (1980) Curated by the Melbourne Cinémathèque. 97 mins Unclassified 15+ 105 mins Unclassified 15+* 106 mins M 101 mins M 107 mins M 87 mins Unclassified 18+ Supported by Screen Australia and Film Victoria. Across a five-decade career, Marcello Visconti’s neo-realist influences are The New York Times hailed Germi Scola’s sepia-toned masterwork “For an actress there is no greater gift This work of fearless, self-exculpating Ostensibly a love story, but also a Hailed as his “second first film” after MINI MEMBERSHIP Mastroianni (1924–1996) maintained combined with a dreamlike visual as a master of farce for this tale remains one of the few Italian films than having a camera in front of you.” semi-autobiography is one of Pialat’s character study focusing on behaviour a series of collaborative video works Admission to 3 consecutive nights: a position as one of European cinema’s poetry in this poignant tale of longing of an elegant Sicilian nobleman to truly reckon with pre-World War Isabelle Huppert (1953–) is one of the most painful and revealing films. -

Index Des Revues Des Cahiers Du Cinéma, Óþóõ

Index des revues des Cahiers du Cinéma, óþóÕ Les ó Alfred de Bruno Podalydès . ßßó Ch. G. ¢þ–¢Õ Le Õ¢ h Õß pour Paris deClintEastwood ........................... ßߦ M. M. ß–ßÉ Õ¦ì rue du désert d’Hassen Ferhani . ßßß M. M. Õ¦–Õ¢, C. A. Õ¢–Õä óþþ mètres d’AmeenNayfeh ........................................ ßßß M. M. ì¦ À l’abordage de Guillaume Brac . ßßä O. C.-H. ó¦–ó¢, C. A., E. M. óä–óÉ, C. A., E. M. ìþ–ìó, M. U. ìì–ì¢, P.F. ìä–ìß À nos amours de Maurice Pialat . ßß P.B. Õìó–Õì¢ L’Aaire collective d’Alexander Nanau . ßßÉ R. P. ì Aer Love d’AleemKhan ............................................ ßßÉ L. S. ¦¦ L’Amour existe de Maurice Pialat . ßß M. U. ÕÕß–ÕÕ Les Amours d’Anaïs de Charline Bourgeois-Tacquet . ßßÉ O. C.-H. ìä e Amusement Park deGeorgeA.Romero ............................ ßßß É. L. ìþ Annette de Leos Carax . ßß M. U. Õó–Õ¦, P.F., M. U. Õä–Õß, Ch. G., M. U. Õ–óì, E. K. ó¦, É. T. óä El año del descubrimiento de Luis López Carrasco . ßßó É. T. ¦ä Army of the Dead de Zack Snyder . ßßß Y.S. ¦ì–¦¦ Autour de Jeanne Dielman de Sami Frey . ßßì P.L. äþ–äÕ Aya et la sorcière de Goro Miyazaki . ßß M. M. ¢¦ Bac Nord de Cédric Jimenez . ßß O. C.-H. ¢¦ Back Door to Hell deMonteHellman ............................... ßßß Y.S. –É La Bataille du rail de Jean-Charles Paugam . ßß R. N. ¢¦ Beast from Haunted Cave deMonteHellman ........................ ßßß J.-M. S. Beef House d’Eric Wareheim et Tim Heidecker . -

Cambridge Companion Crime Fiction

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction covers British and American crime fiction from the eighteenth century to the end of the twentieth. As well as discussing the ‘detective’ fiction of writers like Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie and Raymond Chandler, it considers other kinds of fiction where crime plays a substantial part, such as the thriller and spy fiction. It also includes chapters on the treatment of crime in eighteenth-century literature, French and Victorian fiction, women and black detectives, crime in film and on TV, police fiction and postmodernist uses of the detective form. The collection, by an international team of established specialists, offers students invaluable reference material including a chronology and guides to further reading. The volume aims to ensure that its readers will be grounded in the history of crime fiction and its critical reception. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO CRIME FICTION MARTIN PRIESTMAN cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle:www.cambridge.org/9780521803991 © Cambridge University Press 2003 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the -

University of Hertfordshire Jamie Popowich the Endangered Species

Popowich The Endangered species list University of Hertfordshire Jamie Popowich The endangered species list: the mercurial writing of Charles Willeford and the strange case of The Shark-Infested Custard Abstract: In the late 1960s and the early 1970s the crime writer Charles Willeford moved into various other genres. Willeford explored how the solitary, selfish, and obsessive male protagonists of his crime writing responded to the genre in which they featured. The outgrowth of these experiments were the key texts of his career: The Burnt Orange Heresy (1971) and The Shark- Infested Custard (the latter was not published until after Willeford’s death in 1993). These texts were masterworks of the crime fiction genre, pushing its boundaries beyond the realm of the creative work and producing creative-critical texts. Burnt Orange is a hybrid novel that is at once the story of a sociopathic first person narrator and, perhaps more importantly, a commentary on Surrealist and Dadaist art. The Shark-Infested Custard, on the other hand, comprises a quartet of stories less concerned with the hardboiled world of crime and more with how condominium complexes, specifically those for bachelors, were creating lifestyles built on selfishness and possessions. This article will closely examine these texts and Willeford’s genre writing of the 1960s and 1970s (from science fiction to westerns to sports narratives); it will contextualise his work in relation to crime fiction; and finally, it will place Willeford’s work in a broader context than that of the marginalised pulp writer or the writer of the Hoke Mosely novels, on which the majority of scholarly writing on his work has concentrated. -

Road to Nowhere

ROAD TO NOWHERE A picture by Monte Hellman Starring Shannyn Sossamon, Tygh Runyan, Dominique Swain, Cliff De Young, Waylon Payne, John Diehl, Fabio Testi (Press Kit from Venice Film Festival) ROAD TO NOWHERE CAST (in order of appearance) Mitchell Haven Tygh Runyan Nathalie Post Dominique Swain Laurel Graham/Velma Duran Shannyn Sossamon Bobby Billings John Diehl Cary Stewart/Rafe Tachen Cliff de Young Bruno Brotherton Waylon Payne Steve Gates Robert Kolar Jermey Laidlaw Nic Paul Nestor Duran Fabio Testi Desk Clerk Fabio Tricamo Moxie Herself Peter Bart Himself El Cholo Bartender Pete Manos Mallory Mallory Culbert Doc Holliday Bartender Beck Lattimore Man in Bar Thomas Nelson Bonnie Pointer Herself Airplane Coordinator Jim Galan Airplane Pilot Jim Rowell Greg Gregory Rentis Larry Larry Lerner Erik Lathan McKay Joe Watts Michael Bigham Araceli Araceli Lemos Sarah Sarah Dorsey Female Cadaver Mandy Hughes Morgue Technician Cathy Parker Male Cadaver Brett Mann Room Service Waitress Vanessa Golden Cop Voices Dean Person Jared Hellman Jones Clark Guard Mitchell Allen Jenkin PRODUCTION Directed and Produced by Monte Hellman Written and Produced by Steven Gaydos Produced by Melissa Hellman Executive Producers Thomas Nelson, June Nelson Director of Photography Joseph M Civit Edited by Celine Ameslon Production Designed by Laurie Post Music by Tom Russell Co-Producers Peter R J Deyell, Jared Hellman Associate Producers Lea-Beth Shapiro, Robin-John Gibb Costumes Designed by Chelsea Staebell Production Sound by Rich Gavin Visual Effects Supervisor Robert Skotak First Assistant Director Larry Lerner Second Assistant Director Noreen Perez Supervising Sound Editors Ayne O Joujon-Roche, Kelly Cabral Re-Recording Mixers Scott Sanders, Perry Robertson First Assistant Editors Gregory Rentis, Harold Hyde Producers Representative Jonathan Dana Worldwide Sales E1 Entertainment ROAD TO NOWHERE "Well the ditches are on fire, And there ainʼt no higher ground.