The South Carolina Primary Debacle: the Impact of Anderson V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anderson V. South Carolina Election Commission and Anderson V

\\jciprod01\productn\E\ELO\5-1\ELO105.txt unknown Seq: 1 13-AUG-13 13:04 NOTES TALE OF TWO ANDERSONS: ANDERSON V. SOUTH CAROLINA ELECTION COMMISSION AND ANDERSON V. CELEBREZZE – AN EXAMINATION OF THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF SECTION 8-13-1356 OF THE SOUTH CAROLINA CODE OF LAWS FOLLOWING THE 2012 PRIMARY BALLOT ACCESS CONTROVERSY JOHN L. WARREN III* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ......................................... 224 R II. ANDERSON V. SOUTH CAROLINA ELECTION COMMISSION AND THE 2012 SOUTH CAROLINA PRIMARY CONTROVERSY . 228 R A. Title 8, chapter 13, section 1356 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina ...................................... 228 R B. Anderson v. South Carolina Election Commission . 228 R C. Subsequent Challenges in the South Carolina Supreme Court .............................................. 232 R D. Subsequent Challenges in Federal Court ................ 233 R 1. Somers v. South Carolina State Election Commission . 233 R 2. Smith v. South Carolina State Election Commission . 234 R E. Legislative Pushback ................................. 237 R III. RITTER V. BENNETT: A MISSED OPPORTUNITY?............ 239 R A. Title 36, Chapter 25, Section 15 of the Code of Alabama . 239 R B. Ritter v. Bennett ................................... 240 R * John L. Warren III, J.D., Elon University School of Law (expected May 2013). B.A., University of South Carolina – Honors College. (223) \\jciprod01\productn\E\ELO\5-1\ELO105.txt unknown Seq: 2 13-AUG-13 13:04 224 Elon Law Review [Vol. 5: 223 IV. A HYPOTHETICAL CHALLENGE TO THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF SECTION 1356 IN THE CONTEXT OF THE 2012 SOUTH CAROLINA PRIMARIES .................................... 244 R A. Procedural, Standing, and Form of Pleading Issues ...... 244 R 1. Subject Matter Jurisdiction .................... -

2015 Session Ļ

MEMBERS AND OFFICERS OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Ļ 2015 SESSION ļ STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA Biographies and Pictures Addresses and Telephone Numbers District Information District Maps (Excerpt from 2015 Legislative Manual) Corrected to March 24, 2015 EDITED BY CHARLES F. REID, CLERK HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA MEMBERS AND OFFICERS OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Ļ 2015 SESSION ļ STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA Biographies and Pictures Addresses and Telephone Numbers District Information District Maps (Excerpt from 2015 Legislative Manual) Corrected to March 24, 2015 EDITED BY CHARLES F. REID, CLERK HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA THE SENATE Officers of the Senate 1 THE SENATE The Senate is composed of 46 Senators elected on November 6, 2012 for terms of four years (Const. Art. III, Sec. 6). Pursuant to Sec. 2-1-65 of the 1976 Code, as last amended by Act 49 of 1995, each Senator is elected from one of forty-six numbered single-member senatorial districts. Candidates for the office of Senator must be legal residents of the district from which they seek election. Each senatorial district contains a popu- lation of approximately one/forty-sixth of the total popula- tion of the State based on the 2010 Federal Census. First year legislative service stated means the year the Mem- ber attended his first session. Abbreviations: [D] after name indicates Democrat, [R] after name indicates Republican; b. “born”; g. “graduated”; m. “married”; s. “son of”; d. “daughter of.” OFFICERS President, Ex officio, Lieutenant Governor McMASTER, Henry D. [R]— (2015–19)—Atty.; b. -

2020 Silver Elephant Dinner

SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT PRE-RECEPTION SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT GUEST SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT STAFF SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT PRESS SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53RD ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT DINNER • 2020 FTS-SC-RepParty-2020-SilverElephantProgram.indd 1 9/8/20 9:50 AM never WELCOME CHAIRMAN DREW MCKISSICK Welcome to the 2020 Silver Elephant Gala! For 53 years, South Carolina Republicans have gathered together each year to forget... celebrate our party’s conservative principles, as well as the donors and activists who help promote those principles in our government. While our Party has enjoyed increasing success in the years since our Elephant Club was formed, we always have to remember that no victories are ever perma- nent. They are dependent on our continuing to be faithful to do the fundamen- tals: communicating a clear conservative message that is relevant to voters, identifying and organizing fellow Republicans, and raising the money to make it all possible. As we gather this evening on the anniversary of the tragic terrorists attacks on our homeland in 2001, we’re reminded about what’s at stake in our elections this year - the protection of our families, our homes, our property, our borders and our fundamental values. This year’s election offers us an incredible opportunity to continue to expand our Party. -

Audit Report

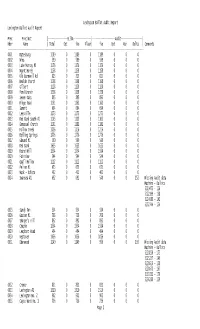

Lexington Ballot Audit Report Lexington Ballot Audit Report Prec Precinct |----------------EL30A---------------|-------------------Audit------------------| Nber Name | Total Opt iVo Flash| iVo Opt Man Delta | Comments ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 0001 Batesburg 1189 0 1189 0 1189 0 0 0 0002 Mims 599 0 599 0 599 0 0 0 0003 Lake Murray #1 1176 0 1176 0 1176 0 0 0 0004 Mount Horeb 1158 0 1158 0 1158 0 0 0 0005 Old Barnwell Rd 825 0 825 0 825 0 0 0 0006 Beulah Church 1168 0 1168 0 1168 0 0 0 0007 Gilbert 1128 0 1128 0 1128 0 0 0 0008 Pond Branch 1338 0 1338 0 1338 0 0 0 0009 Seven Oaks 895 0 895 0 895 0 0 0 0010 Ridge Road 1161 0 1161 0 1161 0 0 0 0011 Summit 694 0 694 0 694 0 0 0 0012 Leesville 1273 0 1273 0 1273 0 0 0 0013 Red Bank South #1 1105 0 1105 0 1105 0 0 0 0014 Emmanuel Church 1181 0 1181 0 1181 0 0 0 0015 Hollow Creek 1216 0 1216 0 1216 0 0 0 0016 Boiling Springs 1776 0 1776 0 1776 0 0 0 0017 Edmund #1 560 0 560 0 560 0 0 0 0018 Red Bank 1635 0 1635 0 1635 0 0 0 0019 Round Hill 1554 0 1554 0 1554 0 0 0 0020 Fairview 544 0 544 0 544 0 0 0 0021 Quail Hollow 1112 0 1112 0 1112 0 0 0 0022 Pelion #1 675 0 675 0 675 0 0 0 0023 Mack - Edisto 402 0 402 0 402 0 0 0 0024 Swansea #1 692 0 692 0 540 0 0 152 Missing Audit data Machine - Ballots 5119473 - 126 5122199 - 138 5124688 - 142 5132744 - 134 0025 Sandy Run 554 0 554 0 554 0 0 0 0026 Gaston #1 708 0 708 0 708 0 0 0 0027 Sharpe's Hill 892 0 892 0 892 0 0 0 0028 Chapin 1554 0 1554 0 1554 0 0 0 0029 Leaphart Road 494 0 494 0 494 0 0 0 0030 Westover 1056 0 1056 0 1056 0 0 0 0031 Edenwood 1149 0 1149 0 956 0 0 193 Missing Audit data Machine - Ballots 5120230 - 173 5125257 - 140 5128616 - 158 5128673 - 167 5131833 - 179 5136288 - 139 0032 Cromer 831 0 831 0 831 0 0 0 0033 Lexington #1 1510 0 1510 0 1510 0 0 0 0034 Lexington No. -

2010 Arts Advocacy Handbook

2010 ARTS ADVOCACY HANDBOOK Celebrating 30 Years of Service to the Arts January 2010 Dear Arts Leader: As we celebrate our 30th year of service to the arts, we know that “Art Works in South Carolina” – in our classrooms and in our communities. We also know that effective advocacy must take place every day! And there has never been a more important time to advocate for the arts than NOW. With drastic funding reductions to the South Carolina Arts Commission and arts education programs within the S. C. Department of Education, state arts funding has never been more in jeopardy. On February 2nd, the South Carolina Arts Alliance will host Arts Advocacy Day – a special opportunity to celebrate the arts – to gather with colleagues and legislators – and to express support for state funding of the arts and arts education! Meet us at the Statehouse, 1st floor lobby (enter at the Sumter Street side) by 11:30 AM, to pick up one of our ART WORKS IN SOUTH CAROLINA “hard-hats” and advocacy buttons to wear. If you already have a hat or button, please bring them! We’ll greet Legislators as they arrive on the 1st floor and 2nd floors. From the chamber galleries, you can view the arts being recognized on the House and Senate floors. You may want to “call out” your legislator to let him or her know you are at the Statehouse and plan to attend the Legislative Appreciation Luncheon. Then join arts leaders and legislators at the Legislative Appreciation Luncheon honoring the Legislative Arts Caucus. -

Senate Filings March 30.Xlsx

SC ALLIANCE TO FIX OUR ROADS 2020 SENATE FILINGS APRIL 2, 2020 District Counties Served First (MI) Last / Suffix Party Primary Election General Election 1 OCONEE,PICKENS Thomas C Alexander Republican unopposed unopposed 2 PICKENS Rex Rice Republican unopposed unopposed Craig Wooten Republican Richard Cash* (R) Winner of Republican Primary 3 ANDERSON Richard Cash Republican Craig Wooten (R) Judith Polson (D) Judith Polson Democrat Mike Gambrell Republican Mike Gambrell* (R) 4 ABBEVILLE,ANDERSON,GREENWOOD Jose Villa (D) Jose Villa Democrat Tom Corbin Republican Tom Corbin* (R) Winner of Republican Primary 5 GREENVILLE,SPARTANBURG Dave Edwards (R) Michael McCord (D) Michael McCord Democrat Dave Edwards Republican Dwight A Loftis Republican Dwight Loftis* (R) 6 GREENVILLE Hao Wu (D) Hao Wu Democrat Karl B Allen Democrat Karl Allen* (D) Winner of Democratic Primary 7 GREENVILLE Fletcher Smith Democrat Fletcher Smith (D) Jack Logan (R) Jack Logan Republican Ross Turner Republican Ross Turner* (R) 8 GREENVILLE Janice Curtis (R) Janice S Curtis Republican 9 GREENVILLE,LAURENS Danny Verdin Republican unopposed unopposed Floyd Nicholson Democrat Bryan Hope (R) Winner of Republican Primary 10 ABBEVILLE,GREENWOOD,MCCORMICK,SALUDA Bryan Hope Republican Billy Garrett (R) Floyd Nicholson*(D) Billy Garrett Republican Josh Kimbrell Republican Glenn Reese* (D) 11 SPARTANBURG Glenn Reese Democrat Josh Kimbrell (R) Scott Talley Republican Scott Talley*(R) Winner of Republican Primary 12 GREENVILLE,SPARTANBURG Mark Lynch Republican Mark Lynch (R) Dawn Bingham -

Congressman Tim Scott & Trey Gowdy

UNIFIED UNIFIED How Our Unlikely Friendship Gives Us Hope for a Divided Country SENATOR CONGRESSMAN TIM SCOTT & TREY GOWDY The nonfiction imprint of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Visit Tyndale online at www.tyndale.com. Visit Tyndale Momentum online at www.tyndalemomentum.com. TYNDALE, Tyndale Momentum, and Tyndale’s quill logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. The Tyndale Momentum logo is a trademark of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Tyndale Momentum is the nonfiction imprint of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois. Unified: How Our Unlikely Friendship Gives Us Hope for a Divided Country Copyright © 2018 by Timothy Scott and Harold Watson Gowdy III. All rights reserved. Cover photograph copyright © by Alice Keeney Photography. All rights reserved. Authors’ photographs copyright © by Michael Hudson. All rights reserved. Designed by Mark Anthony Lane II Edited by Dave Lindstedt Published in association with the literary agency of WordServe Literary Group, www.wordserveliterary.com. All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version,® NIV.® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scripture quotations marked KJV are taken from the Holy Bible, King James Version. Scripture quotations marked NASB are taken from the New American Standard Bible,® copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Tyndale House Publishers at [email protected], or call 1-800-323-9400. ISBN 978-1-4964-3041-0 Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Prologue ix 1. -

Office of the President South Carolina Senate

POST OFFICE BOX 142 213 GRESSETTE BUILDING Harvey S. Peeler, Jr. COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA 29202 PRESIDENT OF THE SENATE PHONE: (803) 212-6430 EMAIL: [email protected] Office of the President South Carolina Senate M E M O R A N D U M TO: Senator Thomas Alexander Senator Gerald Malloy Senator Vincent Sheheen Senator Tom Davis Senator Kevin Johnson Senator Katrina Shealy Senator Ross Turner FROM: Harvey S. Peeler, Jr. DATE: May 4, 2020 SUBJECT: President’s Select Committee to Re-Open South Carolina ______________________________________________________________________________ As President of the Senate, I have appointed a Select Committee to Re-Open South Carolina. Senator Thomas Alexander will chair this Select Committee. Other members include Senators Gerald Malloy, Vincent Sheheen, Tom Davis, Kevin Johnson, Katrina Shealy and Ross Turner. As the Select Committee you are charged with accepting any recommendations made by Governor Henry McMaster’s AccelerateSC task force. Recommendations requiring legislative action will be reviewed by you. Legislation will be introduced by you. I ask that the Select Committee to Re-Open South Carolina begin work immediately. There will be many ideas to be considered including best practices for business operations, safe harbors for potential COVID-19 liability, continued workforce development, and addressing the increase in unemployment. If our businesses need tools to return to work, then we need to provide them. If our citizens need our help, then we need to help them. South Carolinians have been in a difficult situation for too long. By transforming the efforts of AccelerateSC into legislative action, the Senate, through Re-Open South Carolina, can do its part to provide that our citizens and our economy are safe and secure. -

SC Senate Education Committee NAME PARTY- EMAIL COLUMBIA HOME DISTRICT PHONE PHONE

United States Parents Involved in Education- South Carolina Chapter SC Senate Education Committee NAME PARTY- EMAIL COLUMBIA HOME DISTRICT PHONE PHONE Greg Hembree R-Horry 28 [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (843) (Chair) 212-6350 222-1001 // Business: (843) 946- 6556 Luke Rankin R-Horry 33 [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (843) 212-6610 626-6269 // Business: (843) 248- 2405 Harvey Peeler R-Cherokee [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (864) (Senate 14 212-6430 489-3766 // President) Business: (864) 489- 9994 Larry Grooms R-Berkley 37 [email protected] Columbia: (803) No home 212-6400 phone number listed Tom Young, Jr. R-Aiken 24 [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (803) 212-6000 215-3631 // Business: (803) 649- 0000 Ross Turner R-Greenville [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (864) 8 212-6148 987-0596 // Business: (864) 288- 9513 Rex Rice R-Pickens 2 [email protected] Columbia: (803) Cell: (864) 212-6116 884-0408 Scott Talley R- [email protected] Columbia: (803) No other Spartanburg 212-6048 phone 12 number listed Shane Massey R-Edgefield [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (803) (majority 25 212-6330 480-0419 // leader) Business: (803) 637- 6200 United States Parents Involved in Education- South Carolina Chapter Richard Cash R-Anderson 3 [email protected] Columbia: (803) Cell: (864) 212-6124 505-2130 Nikki Setzler D-Lexington [email protected] Home: (803) 796- Home: (803) (minority 7573 // Business: 796-7573 // leader) (803) 212-6140 Business: (803) 796- 1285 John D- [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (803) Matthews Orangeburg 212-6056 829-2383 39 Darrell Jackson D-Richland [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (803) 21 212-6048 776-6954 // Business: (803) 771- 0325 Gerald Malloy D-Darlington [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (843) 29 212-6172 332-5533 // Business: (843) 339- 3000 Brad Hutto D- [email protected] Columbia: (803) Home: (803) Orangeburg 212-6140 536-1808 // 40 Business: (803) 534- 5218 Vincent A. -

NATIONAL President/VP Candidate Party Barack Obama/Joe Biden

NATIONAL President/VP Candidate Party Barack Obama/Joe Biden Democratic Mitt Romney/ Paul Ryan Republican Gary Johnson/James Gray Libertarian Virgil Goode/Jim Clymer Constitution Jill Stein/Cheri Honkala Green House of Representatives District Incumbent Opponent 1 Tim Scott (R) Keith Blandford (Lib), Bobbie Rose (D/WF) 2 Joe Wilson (R) 3 Jeff Duncan (R) Brian Ryan B Doyle (D) 4 Trey Gowdy (R) Deb Morrow (D/WF), Jeff Sumerel (Grn) 5 Mick Mulvaney Joyce Knott (D/WF) (R) 6 Jim Clyburn (D) Nammu Muhammad (Grn) 7 Tom Rice* (R) Gloria Bromell Tinubu (D/WF) *indicates a candidate that is not an incumbent STATE Senate 1 Thomas Alexander (R) 2 Larry Martin (R) Rex Rice (pet) 3 Kevin Bryant (R) 4 Billy O’Dell (R) 5 Tom Corbin (R)* 6 Mike Fair (R) Tommie Reece (pet) 7 Karl B Allen (D/WF)* Jane Kizer (R) 8 Ross Turner (R) * 10 Floyd Nicholson (D) Jennings McAbee (R) 11 Glen Reese (D) Keryy Wood (pet) 12 Lee Bright (R) Henri Thompson (D/WF) 13 Shane Martin (R) 14 Harvey Peeler (R) 15 Wes Hayes (R) Joe Thompson (pet) 16 Greg Gregory (R) * 17 Creighton Coleman (D) Bob Carrison (R) 18 Ronnie Cromer (R) 19 John Scott (D) 20 John Courson (R) Robert Rikard (D), Scott West (Green) 21 Darrell Jackson (D) 22 Joel Lourie (D) 23 Jake Knotts (R) Katrina Shealy (pet), David Whetsell (const) 24 Tom Young (R/Petition)* 25 Shane Massey (R) 26 Nikkie Setzler (D) DeeDee Vaughters (R) 27 Vincent Sheheen (D) 28 Greg Hembree (R/Petition) * Butch Johnson (D) 29 Gerald Malloy (D) 30 Kent Williams (D) 31 Hugh Leatherman (R) 32 John Yancey McGill (D) 33 Luke Rankin (R) 34 -

The Last White Election?

mike davis THE LAST WHITE ELECTION? ast september, while Bill Clinton was delighting the 2012 Democratic Convention in Charlotte with his folksy jibe at Mitt Romney for wanting to ‘double up on the trickle down’, a fanatical adherent of Ludwig von Mises, wearing a villainous Lblack cowboy hat and accompanied by a gun-toting bodyguard, captured the national headquarters of the Tea Party movement in Washington, dc. The Jack Palance double in the Stetson was Dick Armey. As House Majority Leader in 1997 he had participated in a botched plot, instigated by Republican Whip Tom DeLay and an obscure Ohio Congressman named John Boehner, to topple House Speaker Newt Gingrich. Now Armey was attempting to wrest total control of FreedomWorks, the organization most responsible for repackaging rank-and-file Republican rage as the ‘Tea Party rebellion’ as well as training and coordinating its activists.1 Tea Party Patriots—a national network with several hundred affiliates—is one of its direct offshoots. As FreedomWorks’ chairperson, Armey symbolized an ideological continuity between the Republican con- gressional landslides of 1994 and 2010, the old ‘Contract with America’ and the new ‘Contract from America’. No one was better credentialed to inflict mortal damage on the myth of conservative solidarity. Only in December did the lurid details of the coup leak to the press. According to the Washington Post, ‘the gun-wielding assistant escorted FreedomWorks’ top two employees off the premises, while Armey sus- pended several others who broke down in sobs at the news.’2 The chief target was Matt Kibbe, the organization’s president and co-author with Armey of the best-selling Give Us Liberty: A Tea Party Manifesto. -

Legislative Scorecard a Message from the President Ted Pitts, President & CEO of the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce

2015 LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD A Message From The President Ted Pitts, President & CEO of the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce For many years, the South Carolina body from even debating a comprehensive infrastructure bill Chamber of Commerce has released the on the floor. Simply put, the inability of the Senate to make any annual Legislative Scorecard because our significant progress on the singular issue of this regular session members want to know how their elected left the business community with insufficient results upon which officials voted on issues important to the to gauge the Senate’s performance. As you will note, the 2015 business community. The 2015 Legislative Scorecard designates the Senate’s work as “in-progress” in an effort Scorecard represents votes on the South to highlight the urgency to address the state’s most important Carolina Chamber’s top priorities, our issues upon their return in January 2016 for the second half of this Competitiveness Agenda. We have laid two-year session. The Chamber will score the Senate’s 2015 votes out how your legislators voted on these as part of their 2016 total score. business issues and also recognize our 2015 Business Advocates. As president and CEO, my main priority is to advocate on behalf of you, South Carolina’s business community. With our unified The business community went into 2015 laser focused on two voices, we will continue to drive the pro-jobs agenda in South priorities: workforce development and infrastructure. Our Carolina and work to make this state the best place in the world focus was no accident.