Across the Shaman's River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haines Borough Table Lists - List of Businesses Alphabetical No Adresses Page: 1 Jan 29, 2021 02:51PM

Haines Borough Table Lists - List of Businesses Alphabetical No Adresses Page: 1 Jan 29, 2021 02:51PM Report Criteria: Business.License status = "Active" Business Activity.Business activity = {<>} "NONPROFIT" {AND} "TOBACCO" License.License balance = {=} 0 Account Number Business Name License Status Business Activity License Balance 3076 18 AA Meadows LLC Active SHORT TERM LODGING .00 1672 22 Dalton Active SHORT TERM LODGING .00 2152 3 Mile Rental Active LONG TERM LEASE .00 2142 3mile Designs Active RETAIL .00 3129 553 Mud Bay Properties, L Active SHORT TERM LODGING .00 586 A & J Enterprises Active CONSTRUCTION .00 870 A Delicate Balance Active LONG TERM LEASE .00 6430 A Sheltered Harbor B & B Active SHORT TERM LODGING .00 3141 Above the River B&B Active SHORT TERM LODGING .00 2118 AccuVein, Inc. Active RETAIL .00 1881 Acme Transfer Co. Active PETROLEUM & AUTO .00 1945 Aframe4u Active LONG TERM LEASE .00 2123 AK Stitchcraft Active RETAIL .00 1211 Ak. Guardhouse Boarding Active SHORT TERM LODGING .00 6981 Ak. Mt. Guides Adventures Active TOURISM .00 1589 Alagnak Holdings LLC Active LONG TERM LEASE .00 8461 Alascom Active SERVICES .00 1692 Alaska Catamaran LLC Active TOURISM .00 3042 Alaska Commercial Divers, Active SERVICES .00 1995 Alaska Creations Active RETAIL .00 1745 Alaska Excursions Active TOURISM .00 1829 Alaska Fixitmen, LLC Active CONSTRUCTION .00 4482 Alaska Fjordlines Express Active TOURISM .00 4483 Alaska Fjordlines Rental Active LONG TERM LEASE .00 4484 Alaska Fjordlines Retail Active TOURISM .00 1287 Alaska Heliskiing Active TOURISM .00 2121 Alaska High Lift Active CONSTRUCTION .00 1777 Alaska Investment Properti Active SHORT TERM LODGING .00 1857 Alaska Map Company Active RETAIL .00 911 Alaska Marine Lines Active SERVICES .00 9111 Alaska Marine Trucking Active SERVICES .00 698 Alaska Mountain Guides Active TOURISM .00 2037 Alaska Outdoor Science Sc Active SERVICES .00 18 Alaska Power Co. -

Haines Borough Table Lists - List of Active Businesses Alphabetical - No Addresses Page: 1 Jul 26, 2019 02:06PM

Haines Borough Table Lists - List of Active Businesses Alphabetical - No Addresses Page: 1 Jul 26, 2019 02:06PM Report Criteria: Business.License status = "Active" Business Activity.Business activity = {<>} "NONPROFIT","TOBACCO" Account Number Business Name License Status Business Activity 3076 18 AA Meadows LLC Active SHORT TERM LODGING 1672 22 Dalton Active SHORT TERM LODGING 12009 33 Mile Roadhouse LLC Active TOBACCO 3129 553 Mud Bay Properties, L Active SHORT TERM LODGING 586 A & J Enterprises Active CONSTRUCTION 870 A Delicate Balance Active LONG TERM LEASE 1885 A Plus A, LLC Active EATING & DRINKING 6430 A Sheltered Harbor B & B Active SHORT TERM LODGING 1680 About Time Handyman Active CONSTRUCTION 3141 Above the River B&B Active SHORT TERM LODGING 1881 Acme Transfer Co. Active PETROLEUM & AUTO 3148 ADCOMM Engineering Co Active SERVICES 1707 Advocare International LP Active RETAIL 1945 Aframe4u Active LONG TERM LEASE 3070 Ak Cross Country Guiding Active TOURISM 1109 Ak. Fair Chase Guiding Active SERVICES 1211 Ak. Guardhouse Boarding Active RETAIL 6981 Ak. Mt. Guides Adventures Active TOURISM 18271 Aktive, LLC Active SERVICES 1589 Alagnak Holdings LLC Active LONG TERM LEASE 8461 Alascom Active SERVICES 1996 Alaska Arts Confluence Active RETAIL 1692 Alaska Catamaran LLC Active TOURISM 5008 Alaska Chilkoot Bear Foun Active NONPROFIT 3042 Alaska Commercial Divers, Active SERVICES 1995 Alaska Creations Active RETAIL 1745 Alaska Excursions Active TOURISM 1829 Alaska Fixitmen, LLC Active CONSTRUCTION 4482 Alaska Fjordlines Express Active -

Advisory Announcement CONTACT: Nicole Zeiser for Immediate Release: May 18, 2021 Haines Area Management Biologist [email protected] (907) 766-2830

Division of Commercial Fisheries Alaska Department of Fish and Game Sam Rabung, Director Doug Vincent-Lang, Commissioner Region I, Petersburg Area Office PO Box 115526 PO Box 667 Juneau, AK 99811-5526 Petersburg, AK 99833 www.adfg.alaska.gov Advisory Announcement CONTACT: Nicole Zeiser For Immediate Release: May 18, 2021 Haines Area Management Biologist [email protected] (907) 766-2830 CHILKAT RIVER AND CHILKAT INLET SUBSISTENCE SALMON FISHING CLOSURE ANNOUNCEMENT The following information pertains to the 2021 Chilkat River and Chilkat Inlet subsistence salmon fisheries. The 2021 Chilkat River Chinook salmon preseason total run forecast is 1,500 large fish, which is below the lower bound of the escapement goal range of 1,750–3,500 fish. The Chilkat River Chinook salmon stock was designated as a stock of management concern at the 2018 BOF meeting after multiple years (2012–2014 and 2016–2018) of failing to achieve escapement. The Alaska Board of Fisheries approved an action plan that outlines specific actions to be taken in the District 15 drift gillnet, troll, sport, personal use, and subsistence fisheries to reduce harvest of Chilkat River Chinook salmon. Salmon fisheries in Lynn Canal and Chilkat Inlet (District 15) are managed under the Lynn Canal and Chilkat River King Salmon Fishery Management Plan (5 AAC 33.384), the Policy for the management of mix stock salmon fisheries, and the 2018 Chilkat River king salmon action plan (https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/FedAidPDFs/RIR.1J.2018.05.pdf). Because of continued poor marine production of Chilkat River Chinook salmon and a poor forecast for 2021, management actions prescribed in the management and action plans will again be taken in the Chilkat Inlet and the Chilkat River subsistence fisheries. -

Chilkat Valley News

Serving Haines and Klukwan, Alaska since 1966 Chilkat Valley News Volume XLV Number 11 Thursday, March 19, 2015 $1 Chilkats King salmon seek top rules tighten protection Chilkat Inlet closed to July 16 By Tom Morphet Department of Fish and Game biologists this week for river outlined new restrictions on area fisheries aimed to By Karen Garcia protect the Chilkat king salmon return, including The Chilkat Indian Village closing Chilkat Inlet to subsistence fishing through is pursuing protections for the July 15. Chilkat River that would prohibit Sport fishing in Chilkat Inlet also will be closed activities affecting the river’s through July 15, with a daily bag limit of one king water quality. in northern Lynn Canal. Regulations on subsistence The village submitted a proposal fishing in the Chilkat River won’t change from last to the Alaska Chilkat Bald Eagle year. Preserve Advisory Council last The subsistence closure – considerably larger week requesting the river be than one proposed three weeks ago by Fish and designated as an Outstanding Game – would match the sportfish closure, which National Resource Water, which was previously set through June. protects waters of exceptional DRAG RACE -- Steve McLaughlin, right, jumps out in front of Rick Campbell Also, commercial gillnet fishing on the west side recreational, environmental during Chilkat Snowburners races on Mosquito Lake Saturday. McLaughlin of Lynn Canal to the Small Boat Harbor will be or ecological significance and topped six competitors in a 48-mile race and also won a 200-yard drag race. About closed for the first two or three weeks of the season, prohibits any degradation of the 100 people turned out for the event that included a picnic. -

Ainealaska S

VISITOR GUIDE HAINEAlaskA S VISITHAINES.COM WELCOME TO HAINES, ALASKA (Roaming River Photography) People all over the world travel to Haines, looking to experience what locals enjoy every day in our unique Alaskan town. Your adventure starts by deciding your mode of transportation and planning how to fit it all in. Nestled between North America’s deepest fjord and the Chilkat Range, get ready to embark on the “best-kept secret.” Explore Haines’ beautiful scenery, plentiful wildlife, cultural facilities and programs, and incredible outdoor recreation opportunities, and so much more! JOIN US! TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Getting to Haines 4 Golden Circle Tour 6 Haines History 8 Wildlife 10 Wild Things, Wild Places 14 Arts & Culture 16 Haines Map 18 Nearby Adventure Cover Photos Colors at Chilkoot Lake, Fishing 20 Accommodations Chilkoot (Tom Ganner) Skiing (Dawson Evenden) Totem Photo (Tom Ganner) 23 Local Listings Eagle (Tom Ganner) Back Cover: Picture Point Published July 2020 (Tom Ganner) Cape Prince Alfred BANKS I VICTORIA ISLAND Sachs Barrow Harbour Bay Wainwright Holman Cambridge Amundsen Beaufort Sea Cape Bathurst Gulf Prudhoe Bay Bering Strait Paulatuk Tuktoyaktuk 246 Kuguktuk Kotzebue Inuvik Selawik Aklavik 80 Seward Coldfoot Fort McPherson Gambell Bettles Old Crow Peninsula 35 Tsiigehtchic Great Nome ARCTIC CIRCLE Bear 116 Lake ST LAWRENCE 66.5˚ ISLAND Eagle Plains Fort Good Hope Yukon River Circle Livengood 231 Norman Wells Bering Sea Unalakleet Mackenzie River FAIRBANKS 5 Eagle YUKON Delta (CANADA) Hooper A L A S K A Junction Chicken -

Haines Coastal Management Plan - 2007 Ii Haines Coastal Management Plan - 2007 Iii Acknowledgements

Haines Coastal Management Program Final Plan Amendment With Assistance from Sheinberg Associates Juneau, Alaska Haines Coastal Management Plan - 2007 ii Haines Coastal Management Plan - 2007 iii Acknowledgements This plan revision and update would not have been possible without the help of many people who gave their time and expertise. Most important were the Haines Coastal District Coordinator Scott Hansen, who produced maps and provided support for meetings and guidance, Borough Manager Robert Venables, and the Haines Borough Planning Commission: Jim Stanford, Chair Harriet Brouillette Bob Cameron Rob Goldberg Lee Heinmiller Bill Stacy Lynda Walker The Haines Borough Mayor and Assembly also contributed to the development of this Plan. They were: Mike Case, Mayor Jerry Lapp, Deputy Mayor Scott Rossman Stephanie Scott Debra Schnabel Norman Smith Herb VanCleve Others who assisted in the development of this plan by providing information or by following its development include local groups such as the Takshanuk Watershed Council and Chilkat Indian Association. State and Federal staff were helpful in their review and comments on resource inventory and analysis and policy development. Gina Shirey-Potts, OPMP was especially attentive and helpful as were Patty Craw, DGGS-ADNR; Joan Dale, SHPO-ADNR; Mike Turek, ADFG; Roy Josephson, Forestry and Roselynn Smith, ADNR. My apologies to anyone inadvertently left off the acknowledgements. Frankie Pillifant, Sheinberg Associates. Haines Coastal Management Plan - 2007 iv Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction................................................................................................... -

Alaska Fish Factor

Is Holland America leaving? - page 3 Meet the candidates - page 4 Serving Haines and Klukwan, Alaska since 1966 Chilkat Valley News Volume XLVIV, Issue 37 Thursday, September 19, 2019 $1.25 CIA applies with state to change Seduction Point to Tlingint ‘Ayiklutu’ By Kyle Clayton band and other seal hunters.” The Chilkoot Indian Association Henry reviewed ship’s logs and has applied with the Alaska His- interviewed Joe Hotch, a Tlingit torical Commission to change the elder, who said the story of the as- name of Seduction Point, the south- sault was passed down through the ern tip of the Chilkat Peninsula, in generations. Hotch told the CVN an effort to expose and change the that multiple women were raped. landmark that hides a dark history. “When I was fishing with my dad “In brief, a Kaagwaantaan wom- ,we drifted by there and he showed an was raped at this spot by Brit- me the (spot) that the women were ish sailors under the command of raped,” Hotch told the CVN this Joseph Whidbey,” Chilkoot Indian week. “They’re doing a good job Association’s Ryan Barber wrote in changing (the name.) The history in his application letter. “The name will never change.” is meant to imply that she seduced The Geographic Names Informa- the sailors.” tion Systems entry for Seduction Barber sourced Dan Henry’s Point states Vancouver named the book “Across the Shaman’s River,” place Seduction Point because of a narrative detailing Tlingit and the “designing nature of the Indians Native history in the Chilkat Valley. whom Lieutenant Joseph Whid- Henry writes that in 1794, when bey encountered there on July 16, Captain George Vancouver’s ships 1794,” according to a U.S. -

A, Index Map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada Showing the Glacierized Areas (Index Map Modi- Fied from Field, 1975A)

Figure 100.—A, Index map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada showing the glacierized areas (index map modi- fied from Field, 1975a). B, Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the St. Elias Mountains in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image from Mike Fleming, USGS, EROS Data Center, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Alaska. K122 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD St. Elias Mountains Introduction Much of the St. Elias Mountains, a 750×180-km mountain system, strad- dles the Alaskan-Canadian border, paralleling the coastline of the northern Gulf of Alaska; about two-thirds of the mountain system is located within Alaska (figs. 1, 100). In both Alaska and Canada, this complex system of mountain ranges along their common border is sometimes referred to as the Icefield Ranges. In Canada, the Icefield Ranges extend from the Province of British Columbia into the Yukon Territory. The Alaskan St. Elias Mountains extend northwest from Lynn Canal, Chilkat Inlet, and Chilkat River on the east; to Cross Sound and Icy Strait on the southeast; to the divide between Waxell Ridge and Barkley Ridge and the western end of the Robinson Moun- tains on the southwest; to Juniper Island, the central Bagley Icefield, the eastern wall of the valley of Tana Glacier, and Tana River on the west; and to Chitistone River and White River on the north and northwest. The boundar- ies presented here are different from Orth’s (1967) description. Several of Orth’s descriptions of the limits of adjacent features and the descriptions of the St. -

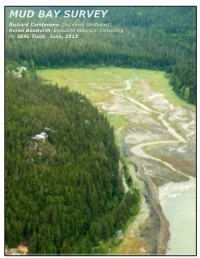

Mud Bay Survey

MUD BAY SURVEY Richard Carstensen Discovery Southeast Koren Bosworth Bosworth Botanical Consulting for SEAL Trust, June, 2013 2 • Mud Bay surveys for SEAL Trust • www.southeastalaskalandtrust.org CONTENTS Navigating this digital journal 1 FIELD JOURNAL .....................................................................3 20130605 FLIGHT TO HAINES ............................................ 3 • ArcMap convention for dates is YYYYMMDD: for exam- ple, 20130605 = June 5, 2013. 20130605 DAY 1 SURVEY ................................................... 3 • This pdf is “bookmarked,” allowing quick navigation STREVELER ON MOOSE & OLD GROWTH ........................... 12 from either the bookmarks tab (left side of Acrobat 20130606 DAY 2 SURVEY ................................................. 19 window) or Contents. Acrobat’s left-arrow button (or alt+backarrow) returns you to your previous position. 2 MUD BAY & CHILKAT PENINSULA ........................................35 • Parts of the journal have 2-page panoramas and are NATURAL & CULTURAL HISTORY ...................................... 35 best viewed in facing-pages mode . To correctly display GEOLOGY.......................................................................... 36 these pages, pull down view>page display>show cover GLACIAL REBOUND .......................................................... 39 page during two-up. • If these tools are missing from your Acrobat header, pull SUCCESSION ON HISTORICAL IMAGERY .......................... 41 down tools>customize toolbars, and check them. -

Haines Borough Table Lists - List of Active Businesses Alphabetical - No Addresses Page: 1 Mar 22, 2018 04:12PM

Haines Borough Table Lists - List of Active Businesses Alphabetical - No Addresses Page: 1 Mar 22, 2018 04:12PM Report Criteria: Business.License status = "Active" Account Number Business Name License Status 3076 18 AA Meadows LLC Active 1672 22 Dalton Active 12009 33 Mile Roadhouse LLC Active 586 A & J Enterprises Active 870 A Delicate Balance Active 1885 A Plus A, LLC Active 6430 A Sheltered Harbor B & B Active 1680 About Time Handyman Active 1881 Acme Transfer Co. Active 1707 Advocare International LP Active 3052 Affordable Cords Active 1945 Aframe4u Active 3070 Ak Cross Country Guiding Active 1109 Ak. Fair Chase Guiding Active 1211 Ak. Guardhouse Boarding Active 6981 Ak. Mt. Guides Adventures Active 18271 Aktive, LLC Active 1589 Alagnak Holdings LLC Active 8461 Alascom Active 3040 Alaska /Canada Firearms T Active 1996 Alaska Arts Confluence Active 5047 Alaska Arts Confluence Active 1692 Alaska Catamaran LLC Active 5008 Alaska Chilkoot Bear Foun Active 3042 Alaska Commercial Divers, Active 1995 Alaska Creations Active 1277 Alaska Discovery Inc. Active 1745 Alaska Excursions Active 4482 Alaska Fjordlines Express Active 4483 Alaska Fjordlines Rental Active 4484 Alaska Fjordlines Retail Active 1287 Alaska Heliskiing Active 5034 Alaska Indian Arts, Inc Active 1818 Alaska Integrated Services Active 12001 Alaska Liquor Store Active 1857 Alaska Map Company Active 911 Alaska Marine Lines Active 9111 Alaska Marine Trucking Active 698 Alaska Mountain Guides Active 1904 Alaska Native Arts and Foo Active 18 Alaska Power Co. Active 254 Alaska Rent A Car Active 9901 Alaska Resources Active 1386 Alaska River Works Active 1418 Alaska Rods Active 2067 Alaska Southeast Elevator Active 12008 Alaska Sport Shop Active 181 Alaska Telephone Co. -

DRAFT—Report to the Alaska Board of Fisheries

DRAFT—Report to the Alaska Board of Fisheries Chilkat River and King Salmon River King Salmon Stock Status and Action Plan, 2018. By Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Staff, Southeast Alaska Region January 2018 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, Special Publications and the Division of Commercial Fisheries Regional Reports. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Administrative fork length FL deciliter dL Code AAC mideye-to-fork MEF gram g all commonly accepted mideye-to-tail-fork METF hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., standard length SL kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. total length TL kilometer km all commonly accepted liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., Mathematics, statistics meter m R.N., etc. all standard mathematical milliliter mL at @ signs, symbols and millimeter mm compass directions: abbreviations east E alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) north N base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s south S catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft west W coefficient of variation CV gallon gal copyright common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) inch in corporate suffixes: confidence interval CI mile mi Company Co. -

Optimal Production of Coho Salmon from the Chilkat River

Fishery Manuscript No. 06-06 Optimal Production of Coho Salmon from the Chilkat River by Randolph P. Ericksen and Steven J. Fleischman November 2006 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Department of fork length FL deciliter dL Fish and Game ADF&G mideye-to-fork MEF gram g Alaska Administrative mideye-to-tail-fork METF hectare ha Code AAC standard length SL kilogram kg all commonly accepted total length TL kilometer km abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., liter L AM, PM, etc. Mathematics, statistics meter m all commonly accepted all standard mathematical milliliter mL professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., signs, symbols and millimeter mm R.N., etc. abbreviations at @ alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) compass directions: base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s east E catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft north N coefficient of variation CV gallon gal south S common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) inch in west W confidence interval CI mile mi copyright © correlation coefficient nautical mile nmi corporate suffixes: (multiple) R ounce oz Company Co.