Meyer V. State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Small Dollar Rule Comments

State Small Dollar Rule Comments All State Commenters State Associations Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Dakota, Oklahoma, • AL // Alabama Consumer Finance Association South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, • GA // Georgia Financial Services Association Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin • ID // Idaho Financial Services Association • IL // Illinois Financial Services Association State Legislators • IN // Indiana Financial Services Association • MN // Minnesota Financial Services Association • MO // Missouri Installment Lenders Association; • AZ // Democratic House group letter: Rep. Stand Up Missouri Debbie McCune Davis, Rep. Jonathan Larkin, • NC // Resident Lenders of North Carolina Rep. Eric Meyer, Rep. Rebecca Rios, Rep. Richard • OK // Independent Finance Institute of Andrade, Rep. Reginald Bolding Jr., Rep. Ceci Oklahoma Velasquez, Rep. Juan Mendez, Rep. Celeste • OR // Oregon Financial Services Association Plumlee, Rep. Lela Alston, Rep. Ken Clark, Rep. • SC // South Carolina Financial Services Mark Cardenas, Rep. Diego Espinoza, Rep. Association Stefanie Mach, Rep. Bruce Wheeler, Rep. Randall • TN // Tennessee Consumer Finance Association Friese, Rep. Matt Kopec, Rep. Albert Hale, Rep. • TX // Texas Consumer Finance Association Jennifer Benally, Rep. Charlene Fernandez, Rep. • VA // Virginia Financial Services Association Lisa Otondo, Rep. Macario Saldate, Rep. Sally Ann • WA // Washington Financial Services Association Gonzales, Rep. Rosanna Gabaldon State Financial Services Regulators -

STATE of ARIZONA OFFICIAL CANVASS 2014 General Election

Report Date/Time: 12/01/2014 07:31 AM STATE OF ARIZONA OFFICIAL CANVASS Page Number 1 2014 General Election - November 4, 2014 Compiled and Issued by the Arizona Secretary of State Apache Cochise Coconino Gila Graham Greenlee La Paz Maricopa Mohave Navajo Pima Pinal Santa Cruz Yavapai Yuma TOTAL Total Eligible Registration 46,181 68,612 70,719 29,472 17,541 4,382 9,061 1,935,729 117,597 56,725 498,657 158,340 22,669 123,301 76,977 3,235,963 Total Ballots Cast 21,324 37,218 37,734 16,161 7,395 1,996 3,575 877,187 47,756 27,943 274,449 72,628 9,674 75,326 27,305 1,537,671 Total Voter Turnout Percent 46.17 54.24 53.36 54.84 42.16 45.55 39.45 45.32 40.61 49.26 55.04 45.87 42.68 61.09 35.47 47.52 PRECINCTS 45 49 71 39 22 8 11 724 73 61 248 102 24 45 44 1,566 U.S. REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS - DISTRICT NO. 1 (DEM) Ann Kirkpatrick * 15,539 --- 23,035 3,165 2,367 925 --- 121 93 13,989 15,330 17,959 --- 4,868 --- 97,391 (REP) Andy Tobin 5,242 --- 13,561 2,357 4,748 960 --- 28 51 13,041 20,837 21,390 --- 5,508 --- 87,723 U.S. REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS - DISTRICT NO. 2 (DEM) Ron Barber --- 14,682 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 94,861 --- --- --- --- 109,543 (NONE) Sampson U. Ramirez (Write-In) --- 2 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 54 --- --- --- --- 56 (REP) Sydney Dudikoff (Write-In) --- 5 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 43 --- --- --- --- 48 (REP) Martha McSally * --- 21,732 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 87,972 --- --- --- --- 109,704 U.S. -

Newsletter 8-14-12

Ward 6 Staff Ward 6 - Newsletter Tucson First August 14, 2012 TPD/TFD Staffing Steve Kozachik Starting in 2015, due to the DROP (Deferred Retire- Council Member ment Option Plan) retirement program, we are going to begin to lose big numbers of our command struc- ture in both of our public safety agencies. In addition, because of the expiration of grant funding related to TPD new hires, the general fund will soon begin to absorb costs that are now being picked up by the Federal money. Ann Charles In short – we are looking at the edge of a cliff when it comes to staffing levels and budget allocations for both police and fire. In rough numbers, right now TPD is down about 40 officers. They’re due to lose another 60 through the DROP. TFD has already made service adjustments to accom- modate for their current staffing levels, but they will lose another 105 firefighters by the end of calendar year 2015. The service changes include converting ladder trucks into Alpha trucks; that is, reducing what was formerly a 4 person crew to two 2 per- Teresa Smith son crews on smaller vehicles, and geared to respond to lower level calls. Neither of those staffing projections takes into account the fact that we will continue to lose officers and firefighters to other locales through normal attrition. With approval from the City Manager’s Office, TFD will be starting a class of 33 firefighter recruits on September 17th with graduation set for February 1st. Typical- ly they lose about 20% of a recruiting class during the academy, and for those who make it through, they’re on probation for 18 months. -

Arizona's House Roster

Arizona’s House Roster Dis Representitive P Phone Fax E-Mail to Fax 01A Karen Fann R 602-926-5874 602-417-3001 [email protected] 01B Noel Campbell R 602-926-3124 602-417-3287 [email protected] 02A John C. Ackerley R 602-926-3077 602-417-3277 [email protected] 02B Rosanna Gabaldón D 602-926-3424 602-417-3129 [email protected] 03A Sally Ann Gonzales D 602-926-3278 602-417-3127 [email protected] 03B Macario Saldate D 602-926-4171 602-417-3162 [email protected] 04A Lisa Otondo D 602-926-3002 602-417-3124 [email protected] 04B Charlene Fernandez D 602-926-3098 602-417-3281 [email protected] 05A Sonny Borrelli R 602-926-5051 602-417-3153 [email protected] 05B Regina Cobb R 602-926-3126 602-417-3289 [email protected] 06A Bob Thorpe R 602-926-5219 602-417-3118 [email protected] 06B Brenda Barton R 602-926-4129 602-417-3010 [email protected] 07A Jennifer D. Benally D 602-926-3079 602-417-3278 [email protected] 07B Albert Hale D 602-926-4323 602-417-3160 [email protected] 08A Thomas "T.J." Shope R 602-926-3012 602-417-3123 [email protected] 08B Franklin M. Pratt R 602-926-5761 602-417-3023 [email protected] 09A Victoria Steele D 602-926-5683 602-417-3147 [email protected] 09B Randall Friese D 602-926-3138 602-417-3272 [email protected] Bruce Wheeler 10A D 602-926-3300 602-417-3028 [email protected] Assistant Min Leader 10B Stefanie Mach D 602-926-3398 602-417-3126 [email protected] 11A Mark Finchem R 602-926-3122 602-417-3286 [email protected] 11B Vince Leach R 602-926-3106 602-417-3284 [email protected] 12A Edwin Farnsworth R 602-926-5735 602-417-3122 [email protected] 12B Warren Petersen R 602-926-4136 602-417-3222 [email protected] Steve Montenegro 13A R 602-926-5955 602-417-3168 [email protected] Majority Leader 13B Darin Mitchell R 602-926-5894 602-417-3012 [email protected] 14A David Stevens R 602-926-4321 602-417-3146 [email protected] David Gowan Sr. -

Final Vote SB 1318 2015 Legislative Session Arizona House Of

Final Vote SB 1318 2015 Legislative Session Arizona House of Representatives Y=33; N=24; NV=3 Legislator Vote Legislator Vote Legislator Vote Legislator Vote Rep. Chris Ackerley N Rep. John Allen Y Rep. Lela Alston N Rep. Macario Saldate N Rep. Richard Andrade N Rep. Brenda Barton Y Rep. Jennifer Benally N Rep. Victoria Steele N Rep. Reginald Bolding N Rep. Sonny Borrelli Y Rep. Russell Bowers Y Rep. Kelly Townsend Y Rep. Paul Boyer Y Rep. Kate Brophy McGee Y Rep. Noel Campbell Y Rep. Jeff Wagner Y Rep. Mark Cardenas N Rep. Heather Carter NV Rep. Ken Clark N Rep. Andrew Sherwood N Rep. Regina Cobb Y Rep. Doug Coleman Y Rep. Diego Espinoza N Rep. David Stevens Y Rep. Karen Fann Y Rep. Edwin Farnsworth Y Rep. Charlene Fernandez N Rep. Michelle Ugenti Y Rep. Mark Finchem Y Rep. Randall Friese N Rep. Rosanna Gabaldon N Rep. Bruce Wheeler N Rep. Sally Ann Gonzales N Rep. Rick Gray Y Rep. Albert Hale N Rep. TJ Shope Y Rep. Anthony Kern Y Rep. Jonathan Larkin NV Rep. Jay Lawrence Y Rep. Bob Thorpe Y Rep. Vincent Leach Y Rep. David Livingston Y Rep. Phil Lovas Y Rep. Ceci Velasquez N Rep. Stefanie Mach N Rep. Debbie McCune Davis N Rep. Juan Mendez N Rep. David Gowen Y Rep. JD Mesnard Y Rep. Eric Meyer NV Rep. Darin Mitchell Y Rep. Rebecca Rios N Rep. Steve Montenegro Y Rep. Jill Norgaard Y Rep. Justin Olson Y Rep. Tony Rivero Y Rep. Lisa Otondo N Rep. Warren Peterson Y Rep. -

ARIZONA CATHOLIC CONFERENCE Diocese of Gallup H Diocese of Phoenix H Diocese of Tucson Holy Protection of Mary Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Phoenix

ARIZONA CATHOLIC CONFERENCE Diocese of Gallup H Diocese of Phoenix H Diocese of Tucson Holy Protection of Mary Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Phoenix H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H he Arizona Catholic Conference (ACC) does not endorse candidates or indicate our www.azredistricting.org/districtlocator. is the public policy arm of the Diocese support or opposition to the questions. All candidates in the aforementioned races Tof Phoenix, the Diocese of Tucson, the Included in the ACC Voters Guide are were sent a survey and asked to respond with Diocese of Gallup, and the Holy Protection of races covering the U.S. Senate, U.S. House of whether they Support (S) or Oppose (O) Mary Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Phoenix. Representatives, Corporation Commission, the given statements. The ACC Voters Guide The ACC is a non-partisan entity and does State Senate and State House. It is important lists every one of these candidates regardless not endorse any candidates. to remember that members of the State of whether they returned a survey. Many The ACC Voters Guide is meant solely Senate and State House are elected by candidates elaborated on their responses, to provide an important educational tool legislative district. Each legislative district indicated by an asterisk, which can be found containing unbiased information on the includes one State Senator and two State online at www.azcatholicconference.org along upcoming elections. Pursuant to Internal Representatives. -

2018 Senate Congressional Primary Election Candidates

2018 Senate Congressional Primary Election Candidates Demographics District Office Candidates1 Party (County) Deedra Aboud DEM Kyrsten Sinema* DEM Angela Green# GRN Adam Kokesh# LBT N/A Statewide Senate Joe Arpaio REP Nicholas Glenn# REP William Gonzales# REP Martha McSally* REP Kelli Ward REP Tom O'Halleran* DEM Coconino, Navajo, Apache, Zhani Doko# LBT Graham, Greenlee, Pinal, District 1 U.S. House Wendy Rogers REP Pima, Yavapai, Gila, Maricopa, Mohave Tiffany Shedd REP Steve Smith REP Matt Heinz DEM Billy Kovacs DEM Ann Kirkpatrick^ DEM Maria Matiella DEM Barbara Sherry DEM District 2 Cochise, Pima U.S. House Yahya Yuksel DEM Bruce Wheeler DEM Lea Marquez Peterson REP Brandon Martin REP Daniel Romero Morales REP Casey Welch REP Raul Grijalva* DEM Joshua Garcia# DEM Santa Cruz, Pima, Maricopa, District 3 U.S. House Sergio Arellano REP Yuma, Pinal Nicolas Peirson REP Edna San Miguel REP David Brill DEM Delina Disanto DEM La Paz, Mohave, Yavapai, District 4 U.S. House # DEM Pinal, Yuma, Maricopa, Gila Ana Maria Perez Haryaksha Gregor Knauer GRN Paul Gosar* REP 1 AZ Secretary of State: 2018 Primary Election: https://apps.arizona.vote/electioninfo/elections/2018-primary- election/federal/1347/3/0, * Current Member ^Former Member #Write In 1 2018 Senate Congressional Primary Election Candidates Demographics District Office Candidates1 Party (County) Joan Greene DEM District 5 Maricopa U.S. House Jose Torres DEM Andy Biggs* REP Anita Malik DEM Garrick McFadden DEM District 6 Maricopa U.S. House Heather Ross DEM David Schweikert* REP Ruben Gallego* DEM District 7 Maricopa U.S. House Catherine Miranda DEM Gary Swing# GRN Hiral Tipirneni DEM District 8 Maricopa U.S. -

Municipal 2012

2012 Municipal policy Statement Core Principles • PROTECTION OF SHARED REVENUES. Arizona’s municipalities rely on the existing state-collected shared revenue system to provide quality services to their residents. The League will resist any attacks on this critical source of funding for localities, which are responsibly managing lean budgets during difficult economic times. The League opposes unfunded legislative mandates, as well as the imposition of fees and assessments on municipalities as a means of shifting the costs of State operations onto cities and towns. In particular, the League opposes any further diversions of Highway User Revenue Fund (HURF) monies away from municipalities and calls upon the Legislature to restore diverted HURF funding to critical road and street projects. • PRESERVATION OF LOCAL CONTROL. The League calls upon the Arizona Legislature to respect the authority of cities and towns to govern their communities free from legislative interference and the imposi- tion of regulatory burdens. The League shares the sentiments of Governor Brewer, who, in vetoing anti-city legislation last session, wrote: “I am becoming increasingly concerned that many bills introduced this session micromanage decisions best made at the local level. What happened to the conservative belief that the most effective, responsible and responsive government is government closest to the people?” Fiscal Stewardship The League is prepared to support reasonable reforms to the state revenue system that adhere to the principles of simplicity, fairness and balance and that do not infringe upon the ability of cities and towns to implement tax systems that reflect local priorities and economies. • The League proposes to work with the Legislature to ensure that both the State and municipalities are equipped with the economic development tools they need to help them remain competitive nationally and internationally. -

UA Retiree News the University of Arizona Retirees Association Newsletter

UA Retiree News The University of Arizona Retirees Association Newsletter Volume 36, No. 3 35th Anniversary edition Spring 2015 UARA OFFICE HAS MOVED TO THE BABCOCK BUILDING! On the eve of our 35th Anniversary, our office has moved from the Sun Building to one of the most historical buildings on campus, the Babcock Building, 1717 E. Speedway Blvd., Room #3105. It’s a happy coinci- dence that we are commemorating our own history as we celebrate our anniversary this year. Just as SPRING HAS SPRUNG! exciting is knowing that the previous occupants were In this issue researchers from the Jane Goodall Research Foundation. The ACTIVITIES AND EVENTS research team and office space 1 BATTER UP WITH THE CATS! were referred to as the “Chimpanzoo.” Parking is available with a Retiree 3 UA EMPLOYEE ART EXHIBIT sticker in the Zone 1 lot right outside the building, or the Zone 1 across the 3 UA CARES street (Helen Street/Campbell Avenue). We have discontinued our land line (325-4366). The phone number for UARA is (520) 982-7813 (call or UARA ORGANIZATION text). 1 UARA’S NEW OFFICE 2 LUNCHEONS 2 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 35th ANNIVERSARY SPRING LUNCHEON, MARCH 26, 2015 2 AC MEETINGS LODGE ON THE DESERT 3 SUMMER MAILINGS You should have received a postcard and RSVP form in the mail 4 UARA ON THE WEB announcing this special event at Lodge on the Dessert as UARA celebrates 6 UARA SCHOLARSHIPS its 35th year! If you did not receive a postcard, please call the office right 7 NEWSLETTER SUPPORT away. -

2014 Legislative Summary

51st Legislature, Second Regular Session Arizona Department of Transportation Legislative Summaries 2014 Contents Members of the 51st Legislature…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 SORTED BY Bill Number ADOT-Related Legislative Summaries – Passed…..…………….……………………………….………………....9 ADOT-Related Legislation – Vetoed……………………………………………………………………………………..16 *Information for Legislative Summaries was gathered from Legislation On Line Arizona, Legislative Research Staff, and bill language. **Official copies of all 2014 Chapter Laws and complete files of action for public review (for both the Regular and Special Sessions) are available on-line at www.azleg.gov 1 Government Relations Janice K. Brewer, Governor John S. Halikowski, Director Kevin J. Biesty, Assistant Director 206 S. 17th Ave. Phoenix, AZ 85007 May 13, 2014 John S. Halikowski Director Arizona Department of Transportation 206 S. 17th Avenue. MD 100A Phoenix, Arizona 85007 Subject: 2014 Legislative Summaries Dear Director Halikowski: Attached is the final summary of transportation-related legislation considered during the Second Regular Session of the 51st Legislature. The Second Regular Session ended on April 24, 2014 lasting 101 days. During the session, 1,205 bills, resolutions, and memorials were introduced, of which 278 were signed and 25 were vetoed. This document and Final Summaries from previous years can be found online at: http://www.azdot.gov/about/GovernmentRelations/legislative-summaries Full legislative chapter text, fact sheets, and other legislative information -

Download 2014 Summaries As a High Resolution

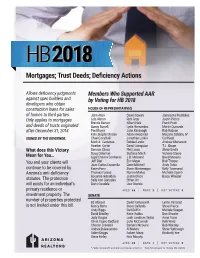

HB2018 Mortgages; Trust Deeds; Deficiency Actions Allows deficiency judgments Members Who Supported AAR against spec builders and by Voting for HB 2018 developers who obtain HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES construction loans for sales of homes to third parties. John Allen David Gowan Jamescita Peshlakai Only applies to mortgages Lela Alston Rick Gray Justin Pierce Brenda Barton Albert Hale Frank Pratt and deeds of trusts originated Sonny Borrelli Lydia Hernandez Martin Quezada after December 31, 2014. Paul Boyer John Kavanagh Bob Robson Kate Brophy McGee Adam Kwasman Macario Saldate, IV SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR. Chad Campbell Jonathan Larkin Carl Seel Mark A. Cardenas Debbie Lesko Andrew Sherwood Heather Carter David Livingston T.J. Shope What does this Victory Demion Clinco Phil Lovas Steve Smith Doug Coleman Stefanie Mach Victoria Steele Mean for You… Lupe Chavira Contreras J.D. Mesnard David Stevens You and your clients will Jeff Dial Eric Meyer Bob Thorpe Juan Carlos Escamilla Darin Mitchell Andy Tobin continue to be covered by Karen Fann Steve Montenegro Kelly Townsend Arizona’s anti-deficiency Thomas Forese Norma Muñoz Michelle Ugenti Rosanna Gabaldón Justin Olson Bruce Wheeler statutes. The protection Sally Ann Gonzales Ethan Orr will exists for an individual’s Doris Goodale Lisa Otondo primary residence or AYES: 55 | NAYS: 2 | NOT VOTING: 3 investment property. The SENATE number of properties protected Ed Ableser David Farnsworth Lynne Pancrazi is not limited under this bill. Nancy Barto Steve Gallardo Steve Pierce Andy Biggs Gail Griffin Michele Reagan David Bradley Katie Hobbs Don Shooter Judy Burges Leah Landrum Taylor Anna Tovar Olivia Cajero Bedford John McComish Kelli Ward Chester Crandell Barbara McGuire Bob Worsley Andrea Dalessandro Al Melvin Steve Yarbrough Adam Driggs Robert Meza Kimberly Yee Steve Farley Rick Murphy AYES: 29 | NAYS: 1 | NOT VOTING: 0 * Eddie Farnsworth and Warren Petersen voted no – they did not want to change the statute. -

Credit Unions Get out the Vote (Cu Gotv) Candidate Info

CREDIT UNIONS GET OUT THE VOTE (CU GOTV) CANDIDATE INFO Redistricting Notice: Listed below are candidates in districts throughout the entire state. Due to redistricting, you may be voting for candidates in districts which are new to you. For additional information please visit Find my district US Senate Richard Carmona (Democrat) PO Box 12399 Tucson, AZ 85732 www.carmonaforarizona.com YouTube Twitter Facebook Jeff Flake (Republican) PO Box 12512 Tempe, AZ 85284 www.jeffflake.com/ YouTube Twitter Facebook Wil Cardon (Republican) 4040 East McClellan Road House 8 Mesa, AZ 85205 http://wilcardon.com/ YouTube Twitter Facebook Bryan Hackbarth (Republican) PO Box 2149 Peoria, AZ 85380 http://www.bryan4senate.com/ Clair Van Steenwyk (Republican) 26682 W. Burnett Rd. Buckeye, AZ 85396 http://www.crossroadswithvan.com/ CREDIT UNIONS GET OUT THE VOTE (CU GOTV) CANDIDATE INFO Congressional District 1 Wenona Benally Baldenegro (Democrat) 2700 Woodlands Village Boulevard Suite 300-203 Flagstaff, AZ 86001 http://wenonaforarizona.com/ Twitter Facebook Ann Kirkpatrick (Democrat) 432 West Cattle Drive Trail Flagstaff, AZ 86001 http://www.kirkpatrickforarizona.com/ YouTube Twitter Facebook Patrick Gatti (Republican) 1100 East Whipple St. Show Low, AZ 85901 http://www.patrickgattiforcongress.com/ Gaither Martin (Republican) 476 North Harless St. Eagar, AZ 85925 http://martin4congress.com/ Twitter Facebook Jonathan Paton (Republican) PO Box 68758 Oro Valley, AZ 85737 http://paton2012.com/ YouTube Twitter Facebook Douglas Wade (Republican) PO Box 388 Sedona, AZ 86339 http://www.wadeforcongress2012.com/ YouTube Twitter Facebook CREDIT UNIONS GET OUT THE VOTE (CU GOTV) CANDIDATE INFO Congressional District 2 Ron Barber (Democrat) 4848 E Hawthorne St. Tucson, AZ 85711 http://ronbarberforcongress.com/ Twitter Facebook Matt Heinz (Democrat) PO Box 2574 Tucson, AZ 85702 http://heinzforcongress.com/ Twitter Facebook Mark Koskiniemi (Republican) PO Box 35487 Tucson, AZ 85731 http://www.koskiniemi4az8.com/ Facebook Martha McSally (Republican) P.O.